Archive:People in the EU - statistics on an ageing society

Data extracted in November and December 2017

This article is outdated and has been archived - for recent articles on Population see here.

Highlights

In 2015, women in the EU could expect to live 63.3 years free from any form of disability, just 0.7 years more than men.

In 2012, 7 % of the women aged 55-69 years in the EU and 6 % of men had reduced their working hours as they approached retirement.

In 2016, close to half of all elderly people aged 65-74 years used the internet at least once a week.

This is one of a set of statistical articles that forms Eurostat’s flagship publication Archive:People in the EU: who are we and how do we live?; it presents a range of statistics that cover elderly persons living in the European Union (EU).

A paper edition of the publication was released in 2015. In late 2017, a decision was taken to update the online version of the publication (subject to data availability). Readers should note that while many of the statistical sources that have been used in People in the EU: who are we and how do we live? have been revised since its initial 2015 release, this was not the case for the population and housing census, as a census is only conducted once every 10 years across the majority of the EU Member States. As a result, the analyses presented often jump between the latest reference period — generally 2015 or 2016 — and historical values for 2011 that reflect the last time a census was conducted.

Full article

European policies relating to health and the elderly

Population ageing is one of the greatest social and economic challenges facing the EU. Projections foresee a growing number and share of elderly persons (aged 65 years and over), with a particularly rapid increase in the number of very old persons (aged 85 years and over). These demographic developments are likely to have a considerable impact on a wide range of policy areas: most directly with respect to the different health and care requirements of the elderly, but also with respect to labour markets, social security and pension systems, economic fortunes, as well as government finances.

EUROPEAN POLICIES RELATING TO HEALTH AND THE ELDERLY

The EU promotes active ageing and designated 2012 as the European year for active ageing and solidarity between generations. It highlighted the potential of older people, promoted their active participation in society and the economy, and aimed to convey a positive image of population ageing. Active ageing means helping people stay in charge of their own lives for as long as possible as they age and, where possible, giving them the opportunity to contribute to the economy and society.

One of the European innovation partnerships concerns active and healthy ageing. Its aim is to tackle the challenges associated with an ageing population, setting a target of raising the healthy lifespan of EU citizens by two years by 2020. In 2012, the European Commission adopted a Communication on ‘Taking forward the strategic implementation plan of the European innovation partnership on active and healthy ageing’ (COM(2012) 83 final). The partnership aims to: enable older people to live longer, healthier and more independent lives; improve the sustainability and efficiency of health and care systems; and to create growth and market opportunities for business in relation to the ageing society. Indeed, the EU’s Social Protection Committee is looking at ways of making adequate provision of long-term care sustainable in ageing societies, by investing in prevention, rehabilitation, age-friendly environments and more ways of delivering care that are better adjusted to people’s needs and remaining capacities.

The EU’s structural funds provide possibilities to support research, innovation and other measures for active and healthy ageing. Active ageing is an important area of social investment, as emphasised in the European Commission’s Communication ‘Towards social investment for growth and cohesion’ (COM(2013) 83 final) and is consequently one of the investment priorities of the European Social Fund (ESF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) during the 2014-2020 programming period.

For those senior citizens who remain in good health, some will decide to continue at work or become active in voluntary work, while others may join a variety of social groups, return to education, develop new skills, or choose to use their free time for travelling or other activities. As life expectancy continues to rise, the constraints, perceptions and requirements of retirement are changing; many of these issues are explored within this article.

Healthy life years

Life expectancy has risen systematically in all of the EU Member States in recent decades; note in 2015 there was a modest fall in EU-28 life expectancy to 80.6 years. Historically, the main reason for the increase in life expectancy was declining infant mortality rates, although once these were reduced to very low levels, the increases continued, largely as a result of declining mortality rates for older people, due for example to medical advances and medical care, as well as improved working and living conditions. Nevertheless, there are considerable differences in life expectancy both between and within Member States; more information is presented in an article on Archive:Demographic changes — profile of the population.

While it is broadly positive that life expectancy continues to rise and each person has a good chance of living longer, it is not so clear that additional years of life are welcome if characterised by a range of medical problems, disability, or mental illness. Indicators on healthy life years combine information on mortality with data on health status (disabilities). They provide an indication as to the number of remaining years that a person of a particular age can expect to live free from any form of disability, introducing the concept of quality of life into an analysis of longevity. These indicators can be used, among others, to monitor the progress being made in relation to the quality and sustainability of healthcare.

In 2015, women in the EU could expect to live 63.3 years free from any form of disability, just 0.7 years more than men …

Eurostat statistics on mortality are based on the annual demographic data collection. They show that the average life expectancy of a girl born in 2015 in the EU-28 was 83.3 years, while the life expectancy of a boy was 77.9 years. Although women had higher life expectancy than men in all of the EU Member States, there has been a pattern of convergence in recent years.

While life expectancy in the EU-28 tended to rise at a gradual pace, there was a more mixed pattern to developments for the indicator based on healthy life years. Figure 1 shows that a girl born in 2015 could expect to live an average of 63.3 years in a healthy state free from any form of disability, while a new-born boy could expect to live 62.6 years free from disability. The latest data available show that there was a relatively sharp upturn in the number of healthy life years at birth for both men and women in 2015, the first substantial increases recorded since 2008; note this may reflect, at least to some degree, a methodological change introduced in Germany which resulted in a break in series for 2015.

… while the elderly population of Sweden could expect to live longest free from any form of disability

At the age of 65, women in the EU-28 had a life expectancy of 21.2 years, while that for men was some 3.3 years less, at 17.9 years. There were considerable differences between the EU Member States as regards the number of healthy life years at 65 years of age (see Figure 2), while the differences between the sexes were far less pronounced. Indeed, in 2015, both men and women aged 65 years across the EU-28 could expect to live an additional 9.4 years free from disability. Among the EU Member States, the range for women was from a high of 16.8 healthy life years in Sweden to a low of 3.8 years in Slovakia, while for men there was a high of 15.7 healthy life years (also in Sweden) and a low of 4.1 years in Latvia and Slovakia.

In 2015, elderly men in the southern EU Member States enjoyed a longer lifespan free from disability than elderly women

The largest gender gap in favour of women among individual EU Member States was recorded in Sweden, where women at the age of 65 could expect to enjoy an additional 1.1 years of life free from disability (compared with men), while gaps of 0.9 years in favour of women were recorded in Denmark, Germany and France; there were seven other Member States where women registered a higher number of healthy life years than men, while in Estonia and Hungary there was no difference at age 65 in the number of healthy life years between the sexes. By contrast, men could expect to live longer free from disability in 15 of the Member States, including most of the southern Member States (with the exception of Malta). The largest gender gaps in favour of men were recorded in Cyprus, the Netherlands (both 1.1 years), Portugal (1.6 years) and Luxembourg (2.0 years).

Figure 3 combines the information on life expectancy and healthy life years to show what proportion of their remaining lives people aged 65 years could expect to live free from disability. Across the whole of the EU-28, on average, a man aged 65 years could expect to live more than half (52.2 %) of his remaining life free from disability in 2015, while the corresponding share for a woman was lower at 44.4 %. There were seven EU Member States where women aged 65 years could expect to live more than half of their remaining lives free from disability, they were: Sweden, Malta, Germany, Denmark, Ireland, Bulgaria and Belgium. In the same seven Member States, men aged 65 years could also expect to live more than half of their remaining lives free from disability, while this was also the case in six more Member States (the Netherlands, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, Finland, France and the Czech Republic). In all 28 EU Member States, men could expect to live a higher proportion of their remaining lives free from disability than could women; in 2015, the biggest differences between the sexes were recorded in Luxembourg, Portugal, the Netherlands, Spain and Romania.

(% share of remaining life expectancy)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_hlye)

Elderly population structure and dependency rates

Structural changes to the demographics of the EU-28’s population may be largely attributed to the consequences of persistently low birth rates and increasing life expectancy. Eurostat’s annual demography data collection shows there were 510.3 million people living in the EU-28 as of 1 January 2016, of whom almost 98 million were aged 65 years and over; furthermore, 57.1 % of this elderly subpopulation were women.

At the start of 2016, the elderly accounted for more than one fifth of the total number of inhabitants in Italy, Greece, Germany, Portugal, Finland and Bulgaria

The proportion of elderly persons in the population differs greatly from one EU Member State to another. In 2016, it peaked at 22.0 % in Italy, while people aged 65 years and over also accounted for more than one fifth of the total population in Greece (21.3 %), Germany (21.1 %, Portugal (20.7 %), Finland (20.5 %) and Bulgaria (20.4 %). In most of the remaining Member States, the elderly generally accounted for 17.0-20.0 % of the total population, although Poland, Cyprus, Slovakia, Luxembourg and Ireland were below this range; the lowest share of the elderly was recorded in Ireland (13.2 %).

Figure 4 shows that the speed of population ageing varies considerably between the EU Member States. Among the 24 Member States for which a complete set of data are available, the pace of demographic ageing between 1976 and 2016 was most pronounced in Portugal, Italy, Finland, Bulgaria and Greece, while the share of the elderly in the total population rose at a relatively slow pace in Belgium, the United Kingdom, Austria, Ireland and Luxembourg. Some of these differences may be explained by variations in fertility rates.

(% share of total population)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind)

In 2016, it was commonplace to find that the elderly accounted for a high share of the population in rural regions

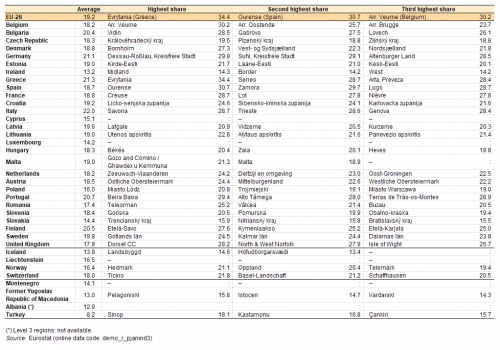

The annual demography data collection also provides a more detailed analysis of population structures for NUTS level 3 regions; Table 1 shows those regions with the highest shares of elderly persons in 2016. Across the whole of the EU-28, the three highest shares were recorded in the central Greek region of Evrytania (34.4 %), the north-western Spanish region of Ourense (30.7 %) and the north-western Belgian region of the Arr. Veurne (30.2 %).

The majority of the regions with high shares of elderly persons were in rural and sometimes quite remote regions, although this pattern was reversed in some of the eastern EU Member States, most notably in Poland, where the highest shares of the elderly were recorded in the cities of Łódź and Warszawa.

(% share of total population)

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_pjanind3)

Table 2 provides similar information (also taken from demography statistics), but focuses on the relationship between the number of elderly persons and those of working-age, otherwise referred to as the old-age dependency ratio. In 2016, those aged 65 years and over were equivalent in number to 63.2 % of the working-age population in Evrytania and also accounted for more than half of the working-age population in Veurne and Ourense, as well as the eastern German region of Dessau-Roßlau, Kreisfreie Stadt. These were the only regions in the EU where there were fewer than two persons of working age for each elderly person in 2016.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_pjanind3)

Elderly population by place of birth

Eurostat’s demography statistics also provide confirmation that in 2016 more than 9 out of every 10 (92.7 %) elderly persons (aged 65 years and over) in the EU were resident in their country of birth, while 4.3 % were born in countries outside of the EU and 3.0 % in another EU Member State (note these averages for the EU exclude Germany).

People born in countries outside the EU, principally Russia, accounted for between one quarter and one third of the elderly residents living in Latvia and Estonia in 2016

There were 10 EU Member States where in excess of 1 in 10 elderly persons were foreign-born, from either another EU Member State or a country outside the EU. In Slovenia, Cyprus, Belgium, Sweden and Austria, the proportion of elderly people who were foreign-born ranged from 10.0-13.0 %, with the elderly born in another EU Member State consistently outnumbering those born in countries outside of the EU.

By contrast, in France, Croatia, Latvia and Estonia, a higher share of the elderly population was born in a country outside the EU, with their share rising close to 3 out of every 10 elderly inhabitants in Latvia and Estonia (27.5 % and 30.0 % respectively). The vast majority of the foreign-born residents in these two Baltic Member States were born in Russia.

In 2016, more than one third (34.9 %) of the elderly population in Luxembourg was composed of people who were foreign-born. The overwhelming share of these were born in another EU Member State (28.8 % of the elderly population in Luxembourg), while 6.1 % were born in a country outside the EU.

(% share of elderly population)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop3ctb)

Senior citizens on the move

Figure 6 shows the proportion of elderly people in the EU who moved during the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census in 2011. Some 2.9 % of the elderly population aged 65-84 years changed residence during this period, which was considerably lower than the average for the whole population (8.3 %); note these figures cover only 20 of the EU Member States as data for Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Spain, Italy, Lithuania, Finland and Sweden are either partially available or not available.

In 2011, elderly persons aged 85 years and over were more likely to move than those aged 65-84 years

There was a higher propensity for people aged 85 years and over to change accommodation: in the 12-month period prior to the census some 5.0 % of those aged 85 years and over in the EU moved home. This may reflect an increasing proportion of the elderly persons moving to live with their relatives or moving into retirement homes or other forms of specialist accommodation.

Many people dream of retiring to another country, especially to a location near the sea and/or in southern Europe. According to results from the population and housing census, the reality is somewhat different as a relatively small number of people in the EU moved abroad during their retirement. In 2011, two thirds (66.6 %) of the elderly persons in the EU aged 65 years and over who changed residence during the 12-month period prior to the census moved within the same NUTS level 3 region, while just over one quarter (28.4 %) moved from another region in the same EU Member State, and 5.1 % moved from outside the reporting country. Nevertheless, there were some destinations that appeared quite popular, as more than one quarter (27.9 %) of the elderly persons who had moved in Greece and around one fifth of the elderly persons who had moved in Cyprus, Luxembourg, Croatia and Malta were from abroad (other EU Member States or countries outside the EU).

The elderly living alone

According to EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), some 14.1% of households in the EU-28 in 2016 were composed of a single person aged 65 years and over. This share ranged from highs of 18.2 % in Bulgaria and 17.4 % in Estonia down to lows of 8.9 % in Luxembourg and 7.0 % in Cyprus.

In 2011, the elderly were more likely to be living alone in urban areas …

The population and housing census allows a more detailed analysis: Map 1 shows that 28.5 % of the EU-28 population aged 65 years and over were living alone in 2011. This share rose as high as 42.4 % in the Danish capital region of Hovedstaden, while the capital regions of Belgium, the United Kingdom and Finland followed with the next highest shares. As such, while a higher proportion of the elderly population lived in rural regions, those who were in urban regions were more likely to be living alone.

At the other end of the range, fewer than 20 % of the population aged 65 years and over were living alone in several Greek, Spanish and Portuguese regions, as well as in Cyprus (a single region at this level of analysis) and the south-eastern Polish region of Podkarpackie; most of these regions were principally rural areas. The lowest share of the elderly living alone — among the NUTS level 2 regions — was recorded in the north-western Spanish region of Galicia (16.8 %).

… while almost half of all women aged 85 years and over were living alone

Women’s longer life expectancy has consequences in relation to the gender gap for elderly persons living alone. According to the population and housing census, there were almost 2.0 million elderly women living alone in the EU-28 in 2011, which equated to more than one third (36.9 %) of all women aged 65 years and over. For comparison, just over one sixth (16.9 %) of all men aged 65 years and over were living alone. Among those aged 85 years and over, the share of the population living alone was considerably higher, reaching 49.5 % for women and 27.8 % for men.

In 2011, most elderly people who lived in institutional households were aged 85 years and over

Contrary to most social surveys, where data collection is usually restricted to private households, the population and housing census may be used to complement analyses of the elderly as it provides a more extensive set of results including information on those persons living in institutional households.

Most elderly people value their independence and would prefer to continue to live in their own homes. In 2011, the proportion of elderly persons in the EU who were aged 65-84 years and living in an institutional household (health care institutions or institutions for retired or elderly persons) was 1.7 %; note there is no information available for Ireland or Finland. Among those aged 85 years and over, this share rose to more than seven times as high, reaching 12.6 % (see Map 2). The proportion of very old women living in an institutional household (14.8 %) was considerably higher than the corresponding share among very old men (7.6 %).

In absolute terms there was almost no difference in the number of elderly people living in institutional households across the EU in 2011: there were 1.35 million persons aged 85 years and over, marginally higher than the 1.34 million aged 65-84 years.

In Luxembourg, almost one third of those aged 85 years and over were resident in an institutional household in 2011

Among NUTS level 2 regions, the highest share of very old persons living in institutional households in 2011 was recorded in Luxembourg (a single region at this level of analysis), almost one third (32.9 %) of the population aged 85 years and over. There were four regions across the EU where shares of 25-30 % were recorded, these included the French regions of Pays de la Loire and Bretagne, the Dutch region of Groningen, and Malta (also a single region at this level of analysis).

By contrast, a small proportion of those aged 85 years and over in Bulgaria, Romania, southern Italy and parts of Greece were living in institutional households. For example, in the three Romanian regions of Sud-Est, Sud-Vest Oltenia and Sud - Muntenia the share of very old persons living in institutional households was no more than 1.0 % (the three lowest regional shares in the EU).

Economically active senior citizens

During the coming years, there are likely to be considerable changes in the demographic profile of the EU’s labour force survey (LFS). Activity rates among people aged 55-64 years increased during the last decade and their growth was unabated during the global financial and economic crisis (despite a reduction in the number of younger persons employed during this period). In the future most commentators expect these patterns to continue, with a growing proportion of the elderly remaining in work for longer, in part due to increases in retirement or pension ages and restrictions on taking early retirement, as well as some people wanting to carry on working and others feeling forced to work for economic reasons.

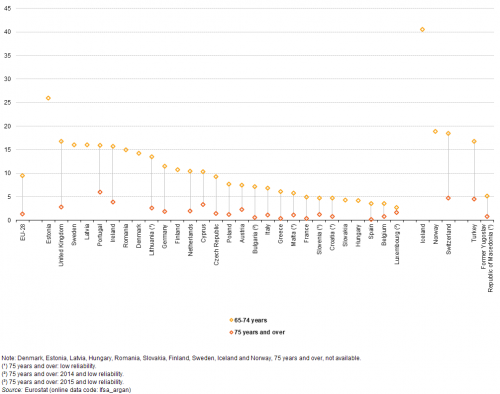

Nevertheless, beyond the age of 65, the share of the population that remains economically active declines sharply. The labour force survey conducted in 2016 shows that there were 4.8 million persons aged 65-74 years in the EU-28 who were economically active (employed or unemployed), while there were an additional 607 thousand active persons aged 75 years and over. The EU-28 activity rate for people aged 65-74 years was 9.5 %, while that for the very old (75 years and over) was 1.4 %.

Just over one quarter of people aged 65-74 years in Estonia remained economically active in 2016 …

In 2016, activity rates among the elderly (aged 65-74 years) were generally at their highest in several northern and western EU Member States. Estonia, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Latvia all reported activity rates of more than 16.0 % (see Figure 7). By far the highest activity rate was recorded in Estonia, where more than one quarter (26.0 %) of the elderly population remained economically active; the next highest share (16.8 %) was recorded in the United Kingdom.

Among people aged 75 years and over, the activity rate peaked at 6.0 % in Portugal, while Ireland (3.9 %) and Cyprus (3.4 %) were the only other Member States (among those for which data are available) to record rates that were above 3.0 % in 2016. One reason for these comparatively high activity rates may be the relatively large share of the population who continue to work in family-run agricultural holdings.

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_argan)

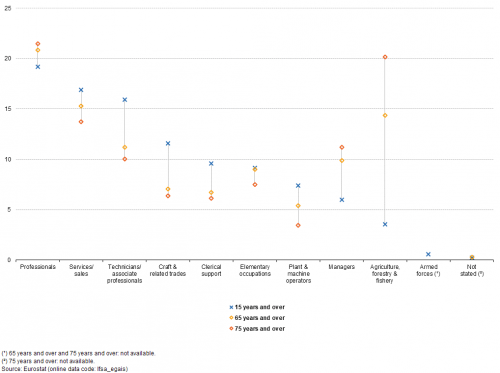

… while a relatively high proportion of elderly farm workers, managers and professionals remained economically active across the EU-28

The results from the labour force survey also enable an analysis of employment patterns according to occupation. In 2016, agriculture, forestry and fishery provided work to 14.3 % of all persons aged 65 years and over who were employed in the EU-28; this share rose to more than one fifth (20.2 %) of the EU-28 workforce when considering people aged 75 years and over. The share of elderly active persons (aged 65 years and over) with an agricultural, forestry or fishing-related occupation was therefore four times as high as the 3.6 % average for the whole population aged 15 years and over. There were only two other occupations — as shown in Figure 8 — where the proportion of the elderly active population (65 years and over) was higher than the average for the whole population, as 9.9 % of the active elderly population were managers (compared with a 6.0 % share for the whole population) and 20.9 % of the active elderly population were professionals (compared with 19.2 %); in both cases this may often concern older people continuing to work in a managerial role in family-run businesses.

(% share of persons employed in each age group)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egais)

In 2012, slightly more than one in five persons in the Netherlands prepared for retirement by reducing their working hours

There are a range of determinants which may impact on decisions linked to older workers’ withdrawal from economic activity, including their income and savings, health, working conditions, and relations with other family members; all of these may play a role when taking decisions linked to transitions into retirement. It is important to note that retirement from paid work does not necessarily imply withdrawal from all types of activity, as an increasing proportion of elderly persons undertake unpaid care activities or are volunteers. Nevertheless, the activity rates and analysis of employment presented here are generally restricted to paid work (as an employee, employer or self-employed person) or as an unpaid family worker within a business (where payment is indirect through the benefits accruing to the family business).

Figure 9 is based on data that have been taken from an ad-hoc module that formed part of the EU’s labour force survey in 2012; it shows information relating to the share of elderly persons who reduced their working hours as they approached retirement. In 2012, some 7.1 % of the women aged 55-69 years surveyed across the EU-28 stated that they had reduced their hours as they approached retirement; this share was somewhat higher than that recorded among men (5.9 %). This pattern was repeated in most of the EU Member States, as the Netherlands, Sweden, Lithuania, Cyprus, Portugal, Spain and Hungary were the only exceptions to report that a higher proportion of men (than women) reduced their working hours (note there is no comparison available for Malta).

There were considerable differences between the EU Member States as regards the share of the elderly population (men and women) who reduced their working hours. In the Netherlands, slightly more than one in five persons (20.5 %) reduced their working hours, while double-digit shares were also recorded in the Nordic Member States, Belgium, the Czech Republic and Malta. By contrast, less than 3.0 % of the elderly populations of Cyprus, Italy, Germany, Spain or Hungary reduced their working hours as they approached retirement.

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (lfso_12reduchrs)

The EU-LFS ad-hoc module for 2012 also collected information in relation to the average age at which an old-age pension was first received. On average, in the EU-28 this was 59.4 years for men and 58.8 years for women; these figures refer to the results of a survey conducted among persons aged 50-69 years. This gender pattern was repeated in the majority of EU Member States, as France, Cyprus, Portugal, Italy, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, Spain and Finland were the only exceptions to report a lower average age for men — in each case this gender gap was no more than 0.7 years.

Figure 10 shows that there was little difference between the sexes in relation to the average age for first receiving an old-age pension for those EU Member States that had the highest average ages. For example, the highest values were reported for Sweden (63.6 years) and the Netherlands (62.7 years) and there was no difference between the sexes for either of these Member States. By contrast, as the average age for first receiving an old-age pension fell the gaps between the sexes tended to increase. Women were more likely to first receive an old-age pension at a younger age than men in all of the eastern EU Member States and the Baltic Member States. This pattern was most apparent in Croatia, where women received a pension, on average, 4.1 years before men; the pattern was repeated in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Poland and Hungary, as in each of these Member States women first received an old-age pension at least 2.3 years before men.

(years)

Source: Eurostat (lfso_12agepens)

Elderly tourists

Travelling around the world is something that many people from all generations enjoy doing. Indeed, many older people take great pleasure from having more spare time in their retirement to be able to travel around their own country, other EU Member States or to destinations that are further afield.

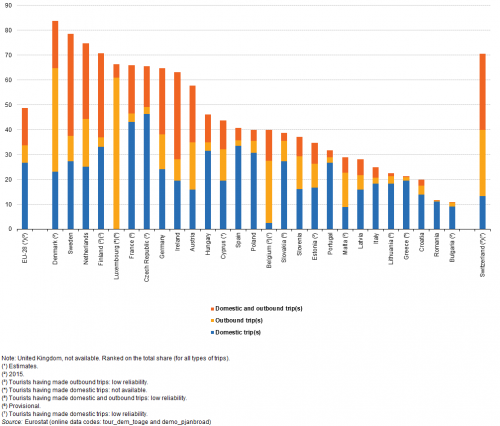

Despite the elderly having more free time to travel, according to Eurostat’s tourism statistics, slightly less than half (48.8 %) of the EU-28 population aged 65 years and over participated in tourism in 2015 (see Figure 11), compared with a 61.3 % share for the population aged 15 years and over.

As with other age groups, the possibilities for enjoying travel and tourism in older age are linked to the availability of income (financial reasons). However, among the elderly the issue of healthy life expectancy is of particular importance: indeed, the propensity for older people to travel diminishes with age, as health issues played a slightly greater role than financial issues in determining whether or not the EU’s elderly population participated in tourism, while a relatively high proportion of the elderly had no motivation to travel/go on holiday.

In 2015, more than four out of every five elderly persons in Denmark went on holiday

In Denmark, more than four out of every five (83.7 %) elderly persons aged 65 years and over participated in tourism in 2015: approximately one quarter of these went only on domestic trips. In 2016, the share of the elderly population participating in tourism was also relatively high in Sweden (78.5 %), the Netherlands (74.7 %) and Finland (70.8 %; 2015 data), while Luxembourg, France, the Czech Republic, Germany and Ireland all recorded shares that were higher than 60 %; note there is no recent information available for the United Kingdom.

By contrast, the share of the elderly population that participated in tourism was generally much lower among most of the southern and eastern EU Member States, as well as the Baltic Member States. In 2016, around one in four elderly persons in Italy made at least one overnight trip (principally within their own country), with somewhat lower shares recorded for the elderly in Lithuania, Greece and Croatia, and much lower shares in Romania (11.6 %) and Bulgaria (11.0 %; 2015 data).

In relative terms, a lower proportion of the elderly population participated in tourism when compared with the corresponding share for the whole adult population aged 15 years and over. This pattern held across all 27 of the EU Member States for which data are available (no recent data for the United Kingdom). In Denmark and Sweden, there was almost no difference between the likelihood of the elderly to participate in tourism and the average for the whole adult population. By contrast, in Lithuania and Bulgaria (2015 data), the proportion of the elderly who participated in tourism was less than one third of the average recorded for the adult population.

(% share of elderly population)

Source: Eurostat (tour_dem_toage) and (demo_pjanbroad)

Senior citizens online — silver surfers

Some senior citizens remain somewhat wary of technology and in particular computers and the internet. That said, a growing proportion of the elderly go online, either as younger generations who have used the internet move into the older age classes, or as people develop internet skills in their old age (perhaps developing these skills once they have taken retirement). Indeed, the internet opens up a wealth of new opportunities and services that may be of particular interest to the elderly.

In 2016, close to half of all elderly people aged 65-74 years used the internet at least once a week …

Eurostat’s statistics on information and communication technologies (ICTs) show that in 2016 close to half (45 %) of the elderly population — defined here as those aged 65-74 years — in the EU-28 used the internet at least once a week. This figure could be compared with the situation a decade earlier in 2006, when just 10 % of the elderly population was using the internet on a regular basis (at least once a week).

Figure 12 also provides information on the share of the elderly population who made daily use of the internet. These statistics show that, once the elderly are confident enough to use technology, they start using the internet actively, just like younger generations. While 60 % of the elderly who used the internet at least once a week in 2006 did so on a daily basis, this share had risen to 80 % by 2016.

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_ci_ifp_fu)

… while more than one quarter of the elderly used the internet for online banking

Table 3 shows that across the whole of the EU-28, just over one quarter (26 %) of elderly persons aged 65-74 years made use of internet banking in 2016; this was approximately half the share recorded for the total population (49 %). A similar share of the elderly used the internet for making online purchases (27 %), while the share of the elderly that used the internet for reading news sites or online newspapers was slightly higher (31 %). By contrast, relatively few elderly persons participated in social networks on the internet (16 %, compared with 52 % of the total population).

In terms of regular use of the internet, there is a relatively large digital divide between northern and western EU Member States on one hand and southern and eastern EU Member States on the other. Luxembourg (88 %), Denmark (81 %), Sweden (80 %) and the Netherlands (77 %), were the only EU Member States where more than three quarters of the elderly population aged 65-74 years used the internet in 2016 at least once a week. On the other hand, in Croatia, Greece, Romania and Bulgaria no more than 16 % of all senior citizens aged 65-74 years went online at least once a week; the next lowest shares were recorded in Lithuania and Poland (both 23 %).

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_bde15cua) and (isoc_bde15cbc)

Source data for tables and graphs

Direct access to

- All articles from Archive:People in the EU: who are we and how do we live?