TestCreation

Data extracted in April 2021.

Planned article update: November 2022.

Highlights

In the EU, the share of persons born outside the EU that were self-employed was 11.7 % in 2020, compared with 11.4 % for persons born in a different EU Member State and 13.9 % for the native-born population.

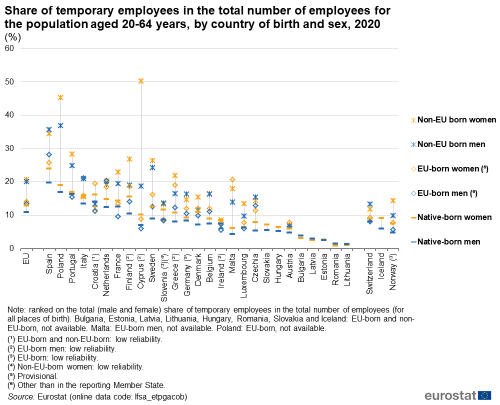

In the EU, more than one fifth (20.3 %) of employees born outside the EU were temporary employees in 2020, compared with 11.8 % for native-born employees and 13.8 % for employees born in a different EU Member State.

In the EU, nearly one quarter (24.2 %) of persons employed who were born outside the EU worked part-time in 2020, compared with 16.9 % for native-born persons in employment and 22.1 % for persons employed who were born in a different EU Member State.

Development of the share of self-employed persons in total employment for the population aged 20-64 years, EU, 2010-2020

This article presents European Union (EU) statistics for a range of employment characteristics, contrasting the situation of migrants with the native-born population; the information may be used as part of an on-going process to monitor and evaluate migrant integration policies. The indicators presented are based on: a set of Council conclusions from 2010 on migrant integration; a subsequent study Indicators of immigrant integration — a pilot study from 2011; and a report titled Using EU indicators of immigrant integration from 2013. The article analyses information from the list of Zaragoza indicators that were agreed by EU Member States in Zaragoza (Spain) in April 2010, alongside additional information derived from the 2013 report on migrant integration. More specifically, it presents statistical data on the following:

- self-employment;

- temporary employees;

- part-time employment.

This article forms part of an online Eurostat publication — Migrant integration statistics.

Full article

Self-employment

Across the EU in 2020, the self-employment share for people aged 20 to 64 years was 11.7 % for those born outside the EU, 11.4 % for those born in another EU Member State and 13.9 % for the native-born population

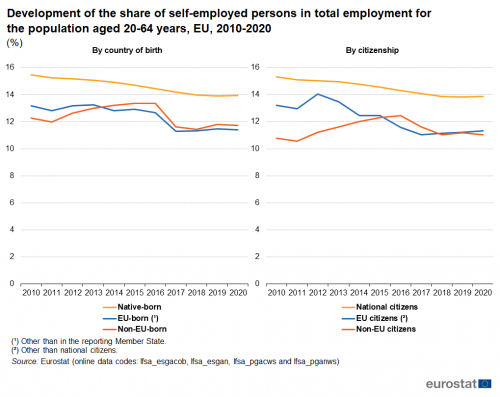

The share of self-employment in the EU for working-age persons who were non-EU-born (in other words, born outside the EU) was slightly lower in 2020 than it had been in 2010: the share in 2020 was 11.7 %, which was 0.5 percentage points lower than the share recorded in 2010 (see Figure 1). However, this share increased between 2011 and 2015 by 1.4 points before falling rapidly in 2017 (down 1.7 points) and thereby reversing all of the increase of the previous years. The share of self-employed persons was also lower in 2020 than it had been in 2010 in both other populations, with a fall for EU-born persons (in other words, those born in a different EU Member State from the one in which they were living) of 1.8 points, while for the native-born population there was a reduction of 1.5 points.

Figure 1 also shows an alternative analysis, namely by citizenship. Across the EU, the share of self-employed persons in total employment among non-EU citizens was 0.2 percentage points higher in 2020 (11.0 %) than it had been in 2010 (10.8 %). This share for non-EU citizens in 2020 was lower than the share for citizens of other EU Member States (11.3 %), which in turn was lower than the share for nationals (13.9 %). The share for nationals was 1.5 points lower in 2020 than it had been in 2010, while for citizens of other EU Member States the share in 2020 was 1.9 points lower than 10 years earlier.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_esgacob), (lfsa_esgan), (lfsa_pgacws) and (lfsa_pganws)

In absolute terms, 25.8 million persons of working-age were self-employed in the EU in 2020. Some 23.0 million of these were native-born, while 2.8 million were foreign-born persons (with a higher share coming from outside the EU). Among the EU Member States, Italy had the largest number of self-employed people (4.5 million working-age persons), accounting for 17.4 % of all self-employed people in the EU, followed by Germany (3.2 million), France (3.1 million), Spain (2.9 million) and Poland (2.9 million).

In relative terms, there was little difference between self-employment shares in the EU when analysing the results for 2020 by country of birth. The share for the working-age native-born population was 13.9 %, while for foreign-born it was lower, at 11.7 % for persons born outside the EU and 11.4 % for those born in a different EU Member State. Among the EU Member States, by far the highest self-employment shares for persons born outside the EU were recorded in Czechia (27.9 %) and Slovakia (24.1 %), with the next highest shares in Malta (20.6 %), Portugal (17.5 %) and the Netherlands (17.3 %) — see Figure 2. By contrast, the lowest shares were recorded in Germany (8.3 %), Sweden (7.7 %), Luxembourg and Austria (both 7.6 %).

For persons born in a different EU Member State, the highest self-employment share in 2020 was recorded in Malta (22.6 %), followed by Slovakia (20.3 %), the Netherlands (17.3 %), Greece (17.0 %), Spain (16.6 %) and Belgium (16.0 %). At the other end of the scale, the lowest self-employment share for persons born in a different EU Member State was registered in Germany (8.2 %), followed by Sweden (8.1 %), Luxembourg (8.0 %), Ireland and Cyprus (both 7.7 %).

Comparing the share of self-employment between the native-born and migrant populations (subject to data availability), there was a mixed pattern across the EU Member States in 2020 (see Figure 2). Greece reported the largest gap when analysing the self-employment shares for persons born outside the EU and those for the native-born population, with the share for the latter being 14.8 percentage points higher; the next largest gaps in this direction were 7.3 points in Italy and 5.4 points in Poland. The largest gap for the opposite situation was observed in Czechia, where the self-employment share recorded for the native-born population was 12.3 points lower than it was for persons born outside the EU; again this was far larger than the next largest gap, 9.4 points in Slovakia.

A similar comparison between the shares of self-employment for the native-born population and persons born in a different EU Member State reveals that there were 10 Member States with a higher share recorded for the native-born population. Among these, the largest gaps were observed in Greece (11.9 percentage points difference) and Italy (9.9 points), while relatively large gaps were also observed in Ireland (5.7 points) and Cyprus (5.5 points). By contrast, the native-born population recorded a lower share of self-employment in 10 Member States, with the gap exceeding 5.0 points in Slovakia (5.6 points) and Malta (9.2 points). In Germany there was no difference between the shares.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_esgacob) and (lfsa_pgacws)

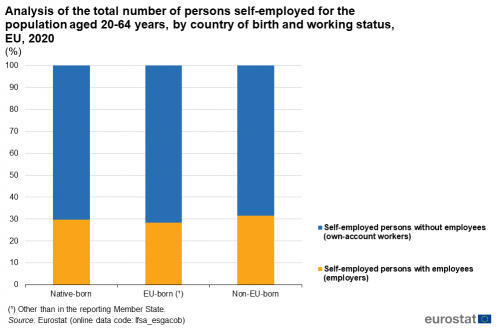

Figure 3 presents an analysis of self-employed persons within the EU by country of birth and according to their working status, with the self-employed split into two distinct groups: self-employed persons with employees (employers) and self-employed persons without employees (also known as own-account workers or sole proprietors). People working on their own account are typically people running their own business, farm or professional practice.

In 2020, 7 in 10 (70.1 %) self-employed persons aged 20-64 years in the EU were own account workers, with the remainder being employers. When analysed by country of birth, the share was marginally higher (70.2 %) for the native-born population and higher still (71.7 %) for people born in other EU Member States. The corresponding share of own account workers among people born outside the EU was lower, at 68.5 %.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_esgacob)

Temporary employment

Among employees born in another EU Member State, the share who were temporary employees in 2020 was considerably lower than in 2010

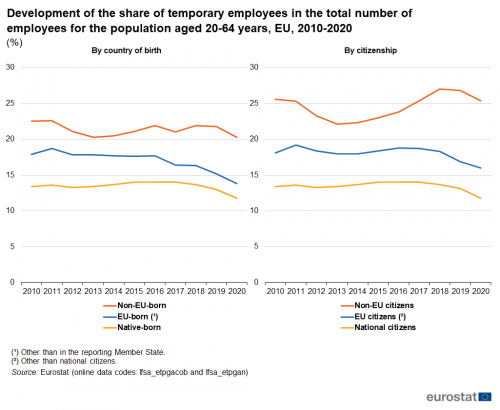

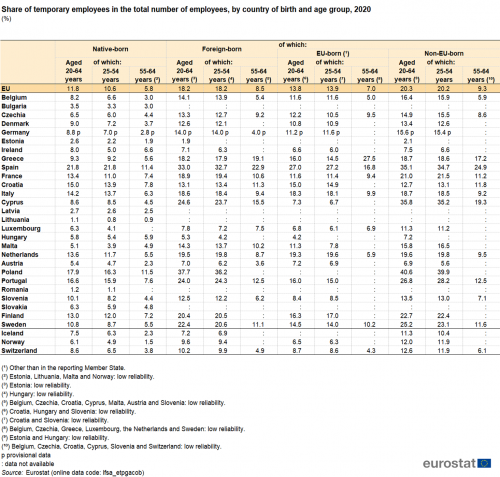

In the EU, temporary employees accounted for an 11.8 % share of the total number of native-born employees in 2020. This was the lowest share during the period 2010 to 2020 (see Figure 4). The corresponding shares for foreign-born employees were higher, as 13.8 % of employees born in another EU Member State were employed on a temporary basis, while the share among employees born outside the EU was 20.3 %. Compared with 2010, the share in 2020 was 1.6 percentage points lower for native-born employees, 2.2 points lower for employees born outside the EU and 4.1 points lower for employees born in another EU Member State.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_etpgacob) and (lfsa_etpgan)

In 2020, the gap between the share of native-born and foreign-born employees aged 20-64 years in the EU who worked on a temporary basis was 6.4 percentage points (see Table 1).

In 2020, the share of temporary employees in the total number of native-born employees peaked in Spain (21.8 %), followed by Poland (17.9 %), Portugal (16.6 %) and Croatia (15.0 %). Among foreign-born employees, the share of temporary employees in the total number of employees was more than one third (37.7 %) in Poland, around one third in Spain (33.0 %) and close to a quarter in Cyprus (24.6 %) and Portugal (24.0 %).

Among the 23 EU Member States for which comparable 2020 data are available, the share of temporary employees was higher for foreign-born employees than it was for the native-born population in all but four. The largest difference was observed in Poland (a gap of 19.8 percentage points); the next highest gaps were recorded in Cyprus (16.0 points), Sweden (11.6 points), Spain (11.2 points), Malta (9.2 points) and Greece (8.9 points). Hungary, Estonia, Ireland and Croatia were the only exceptions, as their share of temporary employees in the total number of employees was lower for foreign-born employees than it was for the native-born population; the gap only exceeded 1.0 point in Croatia (where it was 1.9 points).

There are limited data available for comparing the share of temporary employees between persons born in another EU Member State and persons born outside the EU. For 18 of the 20 EU Member States for which data are available, the share of temporary employees was higher among persons born outside the EU than it was for persons born in another Member State. The largest gap (28.5 percentage points) was recorded in Cyprus, where more than one third (35.8 %) of all employees born outside the EU were employed on a temporary basis, compared with less than one tenth (7.3 %) of their peers who had been born in another Member State. The next largest gaps were recorded in Portugal (10.8 points) and Sweden (10.7 points). By contrast, in Austria the share of temporary employees was slightly higher (0.3 point difference) among people born in another EU Member State than it was for those born outside the EU, while in Croatia the difference was larger (2.3 points).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_etpgacob)

Figure 5 presents an analysis of the share of temporary employees in the total number of employees by country of birth and by sex. In 2020, the share of temporary employees in the total number of employees in the EU was higher among women than men for all populations: native-born employees, employees born in another EU Member State and employees born outside the EU. The largest gap was for native-born employees.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_etpgacob)

Youth temporary employment

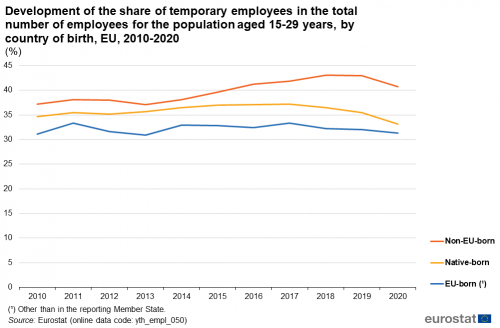

The final two figures within this section on temporary employment provide an analysis of the share of temporary employees in the total number of employees for young people (aged 15-29 years). Figure 6 shows the development of this share in the EU during the period 2010-2020. Among the native-born population aged 15-29 years, the share of temporary employees in the total number of employees increased from 34.7 % in 2010 to reach a peak of 37.2 % in 2017 before falling to 33.1 % in 2020. During this period there were annual falls in 2012 and from 2018 to 2020. For young persons born outside the EU, the share of temporary employees in the total number of employees fluctuated between 37.1 % and 38.1 % between 2010 and 2014. Thereafter it rose each year to reach 43.1 % by 2018; it remained more or less at this level (43.0 %) in 2019 before falling 2.3 percentage points in 2020. For young persons born in another EU Member State, the development was less regular but the share remained in a relatively narrow range, between 30.9 % (observed in 2013) and 33.3 % (observed in 2011 and again in 2017). The share of young employees born in another EU Member State who worked on a temporary basis was almost the same in 2020 as it had been in 2010. Throughout the period shown in Figure 6, the share of temporary employees was lowest for young people born in other Member States and was highest among young persons born outside the EU. In 2020, the gap between the shares for young persons born outside the EU and the young native-born population was 7.6 points, while between the young native-born population and young people born in other Member States it was 1.8 points.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_050)

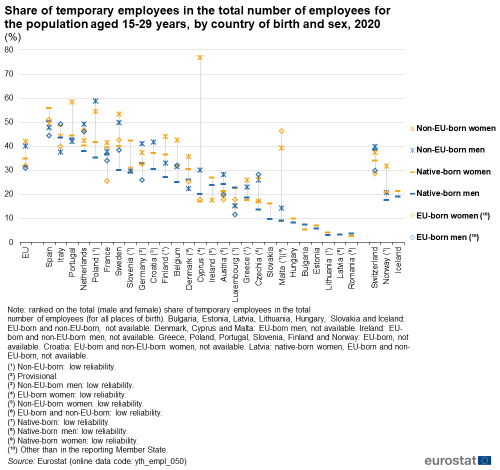

An analysis by EU Member State shows that it was quite common for a relatively large proportion of employees aged 15-29 years to be working on a temporary basis in 2020. This was notably the case in Spain, Italy and Portugal: just over half (52.0 %) of all employees (regardless of where they were born) aged 15-29 years worked on a temporary basis in Spain, 45.0 % in Italy and 44.2 % in Portugal.

Among young persons born outside the EU, the share of temporary employees in the total number of employees (regardless of sex) was highest in Poland, Cyprus, Sweden, Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands. In the case of Poland the share for young men was 58.6 % while for young women it was 54.4 % (see Figure 7). More than half of young women born outside the EU working as employees in Cyprus (76.8 %), Portugal (58.2 %) and Sweden (53.2 %) also worked on a temporary basis, with the share in Spain (49.4%) only slightly lower. Among young men born in another EU Member State, in Italy nearly half (49.1 %) worked on a temporary basis, while among young women born in another EU Member State, more than half (51.0 %) did so in Spain. Among the native-born subpopulation, a majority of young employees in Spain worked on a temporary basis, 50.4 % for young men and 55.8 % for young women. Furthermore, close to half (48.6 %) of young, native-born, female employees worked on a temporary basis in Italy.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_050)

Part-time employment

The share of the EU workforce aged 20-64 years working on a part-time basis rose faster between 2010 and 2020 among foreign-born people than among the native-born subpopulation

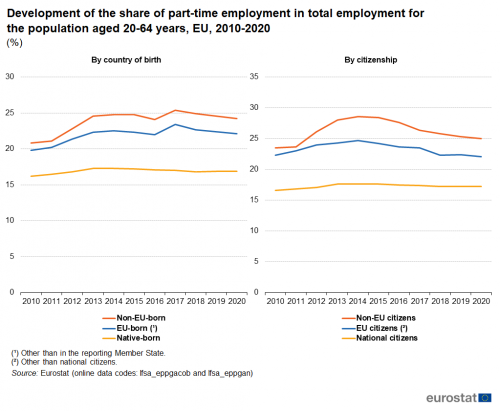

The share of part-time employment in total employment increased steadily in the EU during the most recent 10 year period. This pattern was most apparent among foreign-born populations, with the fastest pace of increase recorded for persons born outside the EU. Figure 8 shows that nearly one quarter (24.2 %) of the EU workforce who was born outside the EU worked on a part-time basis in 2020, while the corresponding share for persons born in another EU Member State was 22.1 % and that for the native-born workforce was lower at 16.9 %. A comparison between 2019 and 2020 reveals that the downturn that started a couple of years earlier continued in 2020 for foreign-born persons working on a part-time basis (both for persons born in another EU Member State and persons born outside the EU). By contrast, there was a more stable development for the share of part-time employment among the native-born workforce, continuing the trend of recent years.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_eppgacob) and (lfsa_eppgan)

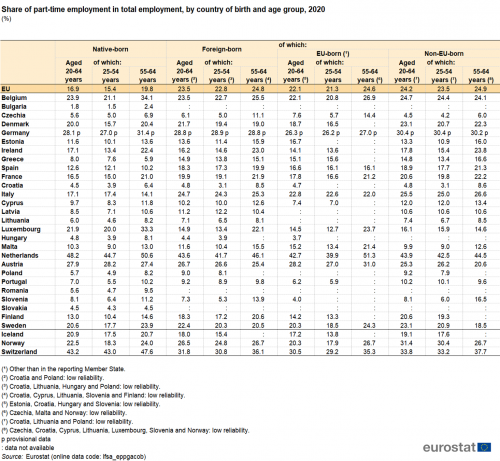

This pattern of a higher share of part-time employment among foreign-born persons — particularly those born outside the EU — was repeated in most of the EU Member States in 2020 (see Table 2). However, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Ireland, Slovenia, Hungary and Belgium reported higher shares of part-time employment among their native-born (rather than foreign-born) workforces; the difference was highest in Luxembourg (7.0 percentage points) and in the Netherlands (4.6 points). However, the share of part-time employment among the foreign-born workforce was 7.6 points higher than the share recorded for the native-born workforce in Italy and 6.9 points higher in Greece; the next largest differences between these two populations were observed in Spain (5.7 points) and Finland (5.3 points).

In 2020, the share of part-time employment in the EU was higher for women compared with men for all subpopulations

In 2020, the share of part-time employment in the EU was higher among women than it was among men. This pattern was observed for all populations in all of the EU Member States (for which data are available), with just one exception: in Cyprus, the share of part-time employment was higher among men (rather than women) born outside the EU. For the native-born workforce (aged 20-64 years), the highest gender gaps in the proportion of people working on a part-time basis were recorded in the Netherlands (51.0 percentage points), Germany (38.8 points) and Austria (38.6 points). The difference between the sexes regarding the tendency to be employed on a part-time basis was generally lower in those Member States where the overall tendency to employ on a part-time basis was below the EU average; the gap between the sexes among the native-born population was less than 1.0 point in Bulgaria and Romania (where relatively few people worked on a part-time basis).

A similar analysis for the foreign-born workforce (aged 20-64 years) shows that the migrant workforce living in the Netherlands, Germany and Austria had a similar pattern to that observed for the native-born workforce, insofar as these EU Member States recorded the largest gender gaps for shares of part-time employment. The share of part-time employment among foreign-born persons was higher among women (than among men) in each of the 21 Member States for which data are available (note: no data or only partial data available for Bulgaria, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia), with the gap between women and men reaching 42.1 percentage points in the Netherlands, 38.9 points in Germany, 35.2 points in Austria, 30.3 points in Belgium and 28.6 points in Italy. By contrast, the lowest gender gaps were recorded for Croatia (where the share of part-time employment for the foreign-born workforce was 1.6 points higher among women than among men) and Cyprus (3.1 points).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_eppgacob)

An analysis by age suggests that older persons (aged 55-64 years) have a higher tendency to work on a part-time basis, although this was not the case for all subpopulations in all EU Member States. In 2020, among the native-born population the share of persons aged 55-64 years working on a part-time basis in the EU (19.8 %) was 4.4 percentage points higher than the share recorded for those aged 25-54 years (15.4 %). This pattern was repeated for the foreign-born workforce when looking at persons born in other EU Member States, as the share of part-time employment among older workers was 3.3 points higher than the share recorded for those aged 25-54 years. For the workforce born outside the EU a smaller difference (1.4 points) was observed: the share of part-time employment recorded for people aged 55-64 years was 24.9 % compared with 23.5 % for people aged 25-54 years.

It is interesting to note that the share of part-time employment was lower for older people (than for those aged 25-54 years) among the native-born population in Greece, Spain, Italy and Austria, and among foreign-born persons in employment in Denmark, Germany, Latvia and Austria. In addition, this share was also lower for older people in at least one (but not both) of the two foreign-born populations in Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal and Sweden.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_eppgacob)

Youth part-time employment

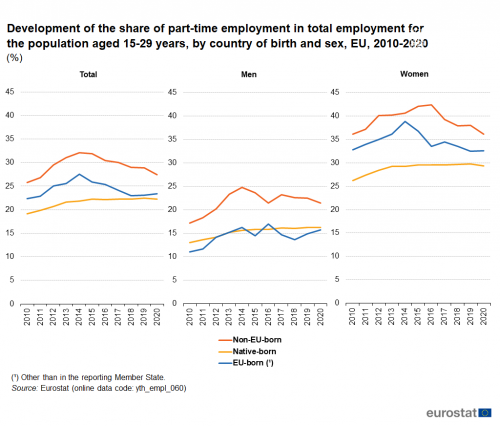

The share of part-time employment for young people (aged 15-29 years) in the EU as a percentage of total employment was higher in 2020 than in 2010, regardless of the country of birth. However, the tendency to employ on a part-time basis fell or stabilised for some groups of young people during the last few years.

Despite falling since 2014, the share of part-time employment among young people born outside the EU was 1.6 percentage points higher across the EU in 2020 than it had been in 2010. There were also increases over this period for the two other populations: the proportion of part-time employment rose by 1.1 points for young people born in another EU Member State, while it increased the most, up 3.1 points, for young native-born people.

Across the whole of the EU, in 2020 the share of part-time employment for young people born outside the EU was 27.4 %, compared with a share of 22.2 % for those who were native-born and 23.4 % for those born in another EU Member State. These aggregate figures (for both sexes) disguise the gender imbalance that exists in relation to part-time employment (see Figure 9), with a higher proportion of young women (than men) in part-time employment. The share of part-time employment among young women born in another EU Member State stood at 32.6 %, which was 16.9 percentage points higher than the corresponding share among young men born in another EU Member State. The differences for the other subpopulations were almost as large, as the share of part-time employment among young women born outside the EU was 36.1 % (14.6 points higher than for young men) and the share for young women who were native-born was 29.3 % (13.1 points higher). For both sexes, the highest share of part-time employment was recorded for young persons born outside the EU. By contrast, the share of part-time employment among young people who were native-born and young people who were born in another EU Member State was quite closely matched in recent years, particularly for young men. The proportion of young men born in another EU Member State who worked on a part-time basis (15.7 %) was lower than the corresponding share for young men who were native-born (16.2 %), whereas for young women the difference was slightly more: 29.3 % of the native-born subpopulation worked on a part-time basis compared with 32.6 % of young women born in another EU Member State.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_060)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The main data source for employment characteristics is the EU labour force survey (EU-LFS). The EU-LFS is a quarterly sample survey that covers the resident population aged 15 years and above in private households. The survey is designed to provide population estimates for a set of main labour market characteristics, covering subjects such as employment, unemployment, economic inactivity and hours of work, as well as providing analyses for a range of socio-demographic characteristics, such as sex, age, educational attainment, occupation, household characteristics and region of residence.

The results from the survey currently cover all European Union Member States, the EFTA Member States Iceland, Norway and Switzerland, as well as the candidate countries Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey. For Cyprus, the survey covers only the areas of Cyprus controlled by the Government of the Republic of Cyprus.

A set of Council, European Parliament and European Commission regulations define how the EU-LFS is carried out, whereas some countries have their own national legislation for the implementation of the survey. The key advantage when using EU-LFS data is that they come from a survey which is highly harmonised and optimised for comparability. However, there are some limitations when considering the coverage of the EU-LFS for migrant subpopulations, as the EU-LFS was designed to target the whole resident population and not specific subgroups, such as migrants. The following issues should be noted when analysing migrant integration statistics:

- recently arrived migrants — this group of migrants is missing from the sampling frame in every host Member State, which results in under-coverage of the actual migrant subpopulation for EU-LFS statistics;

- non-response — one disadvantage of the EU-LFS is the high percentage of non-response that is recorded among migrant subpopulations which may reflect: language difficulties; misunderstanding concerning the purpose of the survey; difficulties in communicating with the survey interviewer; or fear concerning the negative impact that participation in the survey could have (for example, damaging a migrants chances of receiving the necessary authorisation to remain in the host Member State);

- sample size — given the EU-LFS is a sample survey, it is possible that some of the results presented for labour market characteristics of migrants are unrepresentative, especially in those EU Member States with small migrant subpopulations (note that for cases where data are considered to be of particularly low reliability, statistics are not published).

This article focuses on comparisons between national and migrant subpopulations. The results for the migrant subpopulation are usually disaggregated into migrants from other EU Member States and migrants from outside the EU; in some cases an additional analysis by age or by sex is presented. Migrant indicators are calculated for two broad groups: the foreign subpopulation determined by country of birth and the foreign subpopulation determined by citizenship. Although providing some main indicators for the latter, this article focuses on information for migrant integration by country of birth (this subpopulation is generally somewhat larger and therefore allows a more complete and robust data set to be presented). That said, results by country of birth are generally representative of those by citizenship.

The following analyses are presented:

For the population by country of birth

- Native-born — the population born in the reporting country;

- Foreign-born — the population born outside the reporting country; subdivided into:

- EU-born — the population born in the EU, except the reporting country; and

- Non-EU-born — the population born in non-EU countries.

For the population by citizenship

- Nationals — the population of citizens of the reporting country;

- Foreign citizens — the non-nationals; subdivided into:

- EU citizens — the citizens of EU Member States, except the reporting country;

- Non-EU citizens — the citizens of non-EU countries.

For the population by age

- 15-29 years — this age cohort represents the youth population;

- 20-64 years — this cohort has been selected as it represents a core working age;

- 25-54 years — this cohort is considered as the most appropriate group for an analysis of the situation of core working-age migrants, as it minimises the effects of migration related to non-economic reasons (for example, educational studies, training or early retirement), while forming a homogenous group that is large enough to produce reliable results;

- 55-64 years — this cohort focuses on older (working-age) migrants.

The indicators in this article use the definitions of the Zaragoza indicators. Note the age groups above may not be the same as presented in Eurostat’s labour market statistics; for this reason results may differ from other results disseminated by Eurostat.

Country note: In Germany, since the first quarter of 2020, the Labour Force Survey (LFS) has been integrated into the newly designed German microcensus as a subsample. Unfortunately, for the LFS, technical issues and the COVID-19 crisis has had a large impact on the data collection processes, resulting in low response rates and a biased sample. Changes in the survey methodology also led to a break in the data series. The published German data are preliminary and may be revised in the future. For more information, see here.

Context

There is a strong link between integration, migration and employment policies since successful integration is necessary for maximising the economic and social benefits of immigration for EU societies and economies. The importance of integration of nationals of non-member countries living legally in the EU Member States and the establishment of policies for a secure labour environment for migrants underwent a considerable development in 2000 when the Racial Equality Directive (2000/43/EC) and the Employment Equality Directive (2000/78/EC) were adopted in order to prohibit discrimination in employment, occupation, social protection education and access to public goods on the grounds of religion or belief, disability, age, or sexual orientation, race and ethnic origin. In July 2011, the European Commission proposed a European agenda for the integration of third-country nationals [1] focusing on actions to increase economic, social, cultural and political participation by migrants. The agenda highlighted challenges that need to be addressed if the EU is to benefit fully from the potential offered by migration and the value of diversity. It also explored the role of countries of origin in the integration process.

With regard to the measurement of migrant integration, the Stockholm Programme for the period 2010-2014 embraced the development of core indicators for the monitoring of the results of integration policies in a limited number of relevant policy areas including employment, education and social inclusion. Through the 2010 Zaragoza Declaration (and the subsequent Council conclusions) Member States identified a number of common indicators (the so-called Zaragoza indicators) and called upon the European Commission to undertake a pilot study examining proposals for common integration indicators and reporting on the availability and quality of the data for a range of harmonised sources necessary for the calculation of these indicators. The proposals in the pilot study were examined and developed in a report published by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs Using EU indicators of immigrant integration.

In July 2015, the European Commission released jointly with the OECD a report on indicators of immigrant integration Settling in — 2015. While in the thematic chapters of this report the analysis is focused on the foreign-born population, there is a specific chapter dealing with the situation of non-EU citizens in the EU, aimed specifically at monitoring the Zaragoza indicators. A second edition of the report was released in 2018.

On 7 June 2016, the European Commission adopted an Action Plan on the integration of third-country nationals. The plan aims to support the integration process of nationals of non-member countries in the EU, including the specific challenges faced by refugees. Actions included in the plan are designed to target key policy priorities such as pre-departure/pre-arrival measures and access to basic services (education, vocational training, labour market integration, health-care and housing).

A new pact on migration and asylum was presented by the European Commission in September 2020. This sought to provide new tools for faster and more integrated procedures, a better management of the Schengen area and borders, as well as flexibility and crisis resilience. The new pact on migration and asylum sets out what is intended to be a fairer, more European approach to managing migration and asylum. It aims to put in place a comprehensive and sustainable policy, providing a humane and effective long-term response to the current challenges of irregular migration, developing legal migration pathways, better integrating refugees and other newcomers, and deepening migration partnerships with countries of origin and transit for mutual benefit.

In November 2020, an Action plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021-2027 (COM(2016) 377 final) was adopted. It seeks to detail targeted and tailored support to reflect the individual characteristics that may present specific challenges to people with a migrant background, such as gender or religious background.

Notes

- ↑ ‘Third-countries’ is a synonym for non-member countries, in other words countries outside of the EU.

Direct access to

- Employment (mii_emp)

- Unemployment (mii_une)

- Long-term unemployment (12 months or more) as a percentage of the total unemployment, by sex, age and citizenship (%) (lfsa_upgan)

- Long-term unemployment (12 months or more) as a percentage of the total unemployment, by sex, age and country of birth (%) (lfsa_upgacob)

- Employment and self-employment (mii_em)

- Employment rates by sex, age and citizenship (%) (lfsa_ergan)

- Employment rates by sex, age and country of birth (%) (lfsa_ergacob)

- Part-time employment as percentage of the total employment, by sex, age and citizenship (%) (lfsa_eppgan)

- Part-time employment as percentage of the total employment, by sex, age and country of birth (%) (lfsa_eppgacob)

- Self-employment by sex, age and citizenship (1 000) (lfsa_esgan)

- Self-employment by sex, age and country of birth (1 000) (lfsa_esgacob)

- Temporary employees as percentage of the total number of employees, by sex, age and citizenship (%) (lfsa_etpgan)

- Temporary employees as percentage of the total number of employees, by sex, age and country of birth (%) (lfsa_etpgacob)

- Unemployment (mii_une)

- LFS series — detailed annual survey results (ESMS metadata file — lfsa_esms)

- Migrant integration — methodology

- European agenda on migration — legislative documents

- Directive 2014/66/EU of 15 May 2014 on the conditions of entry and residence of third-country nationals in the framework of an intra-corporate transfer

- Directive 2011/98/EU of 15 May 2014 on a single application procedure for a single permit for third-country nationals to reside and work in the territory of a Member State and on a common set of rights for third-country workers legally residing in a Member State

- Directive 2009/50/EC of 25 May 2009 on the conditions of entry and residence of third-country nationals for the purposes of highly qualified employment, commonly called the ‘Blue card directive’

- Directive 2003/86/EC of 22 September 2003 on the right to family reunification

- Directive 2000/43/EC of 29 June 2000 implementing the principle of equal treatment between persons irrespective of racial or ethnic origin

- Directive 2000/78/EC of 27 November 2000 establishing a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation

- Conclusions on integration as a driver for development and social cohesion

- European Commission — Directorate-General Migration and Home Affairs — Legal migration and Integration

- European Commission — EU Immigration Portal (EUIP)

- European Commission — New pact on migration and asylum

- European Commission — The 2010 Zaragoza declaration

- European Commission — Using EU Indicators of Immigrant Integration — final report prepared for DG Migration and Home Affairs

- European Migration Network (EMN) — Annual reports on migration and asylum

- European website on integration

- ILO — Migrant integration policy index (MIPEX)

- OECD — International Migration Outlook

- OECD — Settling In 2018 — Indicators of Immigrant Integration