Main characteristics of foreign-born people on the labour market

Data extracted in June 2022

No planned article update

Highlights

Migration shows different patterns across the European Union. Migrants may come from another EU country or from other parts of the world more or less developed (according to the Human Development Index (HDI)). People also migrated for different reasons depending on their country of origin, their age, their personal and family situation, and the host country. For example, in the two first quarters of 2022, millions of Ukrainians entered the EU to get protection under the Temporary Protective Directive, which provides a residence permit and access to the labour market in EU Member States, among other protections, for Ukrainian citizens and third country citizens residing in Ukraine. Some people migrated to a EU country for family reasons while others rather for employment reasons.

This article looks at the profile of foreign-born people, so those who were born in a different country than the country of residence. It provides an overview of foreign-born people broken down by demographic and social characteristics such as sex, age, educational attainment level and country of origin (using the human development index), as well as their employment rate. It also gives an insight into the reasons for migrating as well as into the average duration for foreign-born people to find a job.

Data shown in this article come from the 8-yearly regular module of the Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) on the labour market situation of migrants and their immediate descendants implemented in 2021, as data shown in the associated article Main obstacles for foreign-born people to enter the labour market. Presented statistics cover the European Union (EU) as a whole and its individual Member States, as well as three EFTA countries (Iceland, Norway, Switzerland) and one candidate country (Serbia).

The concept of migration used in this article refers to people residing in a EU Member State and born in another country (inside or outside the EU). It consequently excludes people coming back to their country of birth after having resided in another country for at least 12 months.

Full article

Profile of foreign-born people

Almost 3 in 10 foreign-born people aged 15-74 come from another EU country

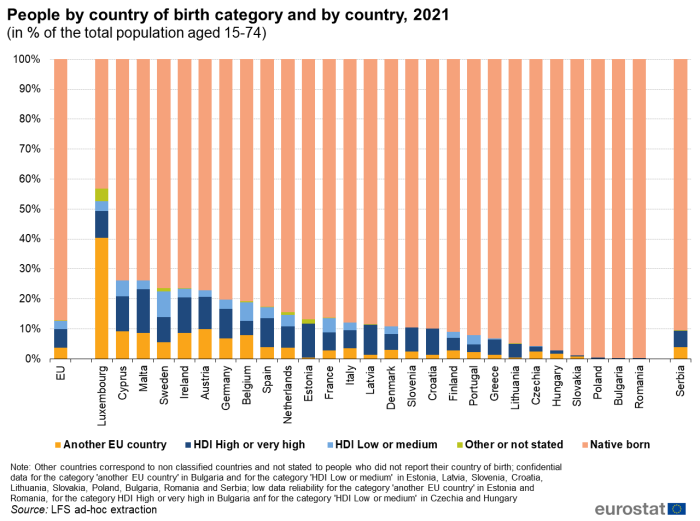

In 2021, in the EU, 42.6 million people, or 12.8 % of the total population, were born in another country than their country of residence as shown in Figure 1.

In this article, the Human Development Index (HDI) is used to group countries of birth according to their level of human development. This index developed by the UN is a 'summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, being knowledgeable and have a decent standard of living' see here for further details. To give some examples of this classification, Australia, Chile, Japan or Malaysia have a very high HDI; China, Bolivia, Ukraine or Thailand have a high HDI, while Bangladesh, Congo, Morocco or India have a medium HDI and Ethiopia, Haiti, Madagascar, Mali, Senegal or Yemen have a low HDI. Note that EU countries have all a very high HDI, but they are always considered apart in the context of this article. EFTA and Candidate countries are in a single group only in Figure 2 but are in the group of 'countries with a high or very high HDI' or of 'countries outside the EU' in the remaining parts of the article.

At national level, more than half of the population in Luxembourg in 2021 was born in another country (56.8 %), the highest share among EU countries. This share is broken down into the following categories: 40.5 % who were born in another EU country, 8.9 % in a non-EU country with a high or very high HDI and 3.3 % in a non-EU country with a low or a medium HDI. Cyprus, Malta Sweden, Ireland and Austria followed at a distance with less than 30 % but still more than 20 % of their population being born in another country. In 2021, less than 1 % of the population in Romania, Bulgaria and Poland were foreign-born.

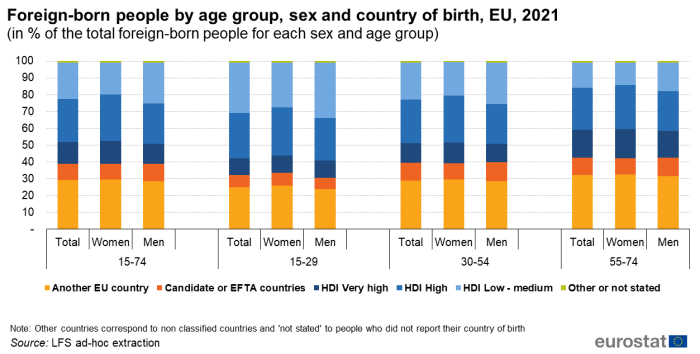

In the EU, 29.1 % of foreign-born people were born in another EU country, 9.8 % were born in an EFTA or candidate country, 12.8 % in a country with a very high HDI, 25.8 % in a country with a high HDI and 21.6 % in a country with a low or medium HDI. These shares vary between men and women and between younger and older people (see Figure 2). Foreign-born men were more likely to be born in a country with a low or medium HDI than foreign-born women and this applies for the whole population aged 15-74 as well as for all age groups (i.e. 15-29, 30-54 and 55-74). Precisely, almost a quarter of foreign-born men aged 15-74 (24.4 %) were born in a country with a low or a medium HDI against slightly less than one fifth of women (19.1 %).

Analysed by age, foreign-born people aged 15-29 were less likely to be born in another EU country (24.9 %) or in a country with a very high HDI (10.1 %) than older people: in 2021, the share of people born in another EU country was 29.0 % among foreign-born people aged 30-54 and 32.0 % among foreign-born people aged 55-74. In the same way, 11.8 % of foreign-born people aged 30-54 and 16.6 % of foreign-born people aged 55-74 were born in a country with a very high HDI. These lower shares among younger people for those born in another EU country or in a non-EU country with a very high HDI are mainly offset by higher shares in people born in a country with a low or a medium HDI.

Country of birth, sex and education: key factors for employment

In 2021, more than half of foreign-born people aged 35 or more from a country with a low or a medium HDI had a low level of education

The level of education varies significantly according to the country of birth and to the age as can be seen in Figure 3. Note: for the purpose of this section, the reference population includes people aged 25-74 in order to better address people with a high level of education and to allow more accurate comparison.

In the EU, 21.8 % of native-born people aged 25-74 had a low level of education in 2021. This share was 26.4 % among people born in another EU country and 33.6 % among people born in a non-EU country with a high or a very high HDI. However, the highest share of people with a low level of education was recorded among people born in a country with a low or a medium HDI: 50.9 % of them had a low level of education. This finding is even more pronounced among younger people (aged 25-34): 45.8 % of people born in a country with a low or a medium HDI had a low level of education, which is close to 4 times the share reported by native-born people (12.2 %).

In general, the younger the person, the higher the level of education, however this pattern varies significantly according to the category of country of birth. Considering native-born people, those born in another EU country and those born in a non-EU country with a high or very high HDI, Figure 3 shows that the shares of people with a high level of education ranged from 21.8 % to 25.7 % among people aged 55-74, from 30.7 % to 35.7 % for people aged 35-54 and from 40.1 % to 42.1 % for younger people aged 25-34, roughly increasing by 10 pp. from one age category to another. This increase is also visible for people born in a country with a low or a medium HDI but to a much lesser extent. Indeed, around 21.4 % of people aged 55-74 had a high level of education against 22.3 % for people aged 35-54 and 25.1 % for those aged 25-34.

Difference larger than 20 pp. between the employment rate of native-born women and of women born in a country with a low or a medium HDI with a high level of education

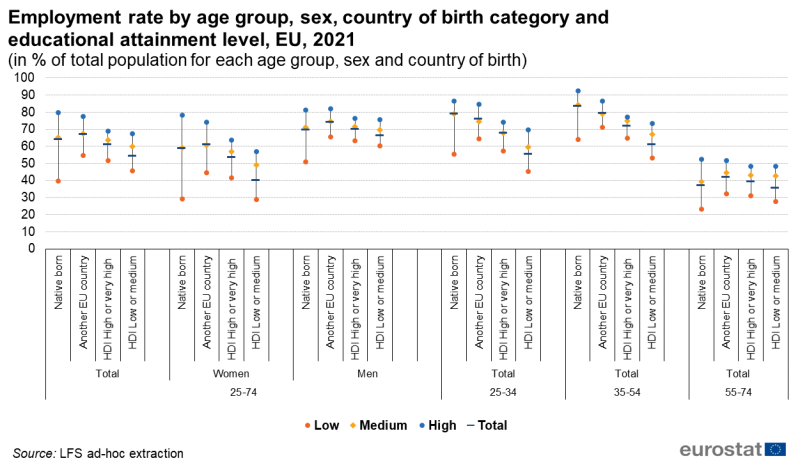

Figure 4 displays the employment rate of people by country of birth, level of education and age group.

- Among people aged 25-74 with a high level of education, native-born people recorded the highest employment rate with 79.7 %, followed by those born in another EU country (77.6 %), those born in a non-EU country with a high or very high HDI (69.0 %) and those born in a country with a low or a medium HDI (67.2 %).

However, this ranking differs among people with a medium and a low level of education.

- For people with a medium level of education, people from another EU country ranked first (67.2 %), followed by the native-born (65.2 %), those born in a non-EU country with a high or very high HDI (63.8 %) and those born in a country with a low or a medium HDI (60.1 %).

- For people with a low level of education, people from another EU country ranked also first (54.7 %) but were followed by those born in a country with a high or very high HDI (51.6 %), those born in a country with a low or a medium HDI (45.7 %) and the native-born (39.8 %).

Considering the same level of education, the gap between the employment rate of the different categories of country of birth are larger for women than for men. The largest gap in the employment rate was found between native-born women and women born in a country with a low or a medium HDI aged 25-74 and with a high level of education (difference of 21.3 pp.). A similar gap was also found between native-born people and people born in a country with a low or a medium HDI aged 25-34 with a medium level of education (19.4 pp.) and for those aged 35-54 with a high level of education (19.1 pp.). Another significant gap was recorded between the employment rate of people born in another EU country and the employment rate of those born in a country with a low or a medium HDI with a low level of education aged 25-34 (19.3 pp.) and aged 35-54 (17.7 pp.).

At country level and considering the population aged 15-74 as reference without addressing the level of education, the employment rate of people born in another EU country was higher in 2021 than the employment rate of native-born people in more than half of the EU countries (18 out of 25 countries for which data is available). Furthermore, the employment rate of native-born people was higher than the employment rate of people born outside the EU in 14 out of 27 EU countries (see Figure 5).

(in % of population aged 15-74)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_ergacob)

Reasons for migrating

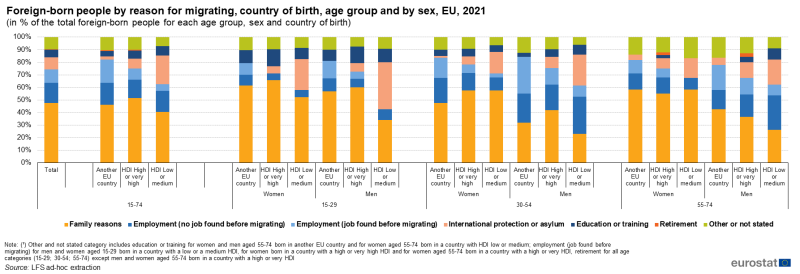

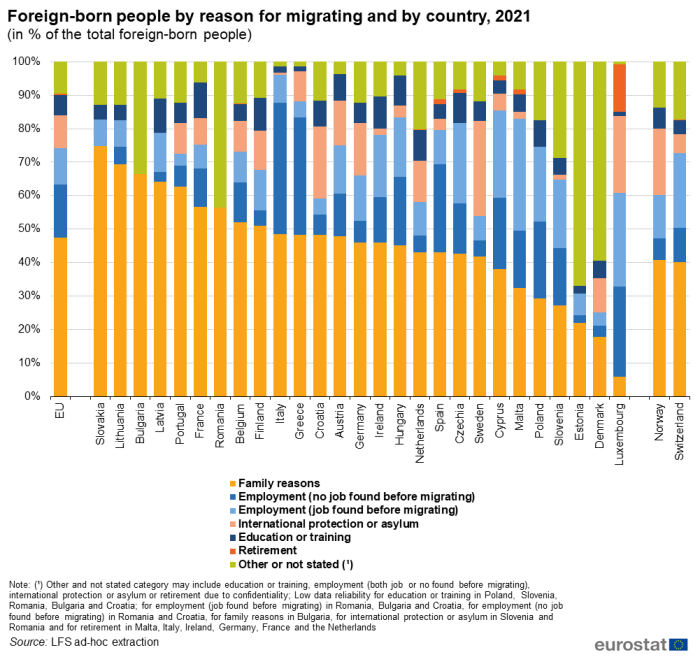

In 2021, almost half of the foreign-born people in the EU migrated for family reasons (47.4 % of total foreign-born people aged 15-74). This is the first reason for all categories of country of birth. Family reasons were followed at a distance by reasons related to employment: 16.0 % of people who were born in another country migrated for work without having found a job before and 10.9 % migrated when they had already found a job in the host country. In addition, 9.6 % migrated for international protection or asylum and 6.1 % for education reasons. A very small share of foreign-born people migrated to retire in the host country (0.5 % of the total) (see Figure 6).

However, reasons for migrating change significantly according to the country of birth, to the age and to the sex.

People born in another EU country were more likely to migrate because they found employment before migrating (18.5 %) than people from outside the EU (8.9 % for people born in a country with a high or a very high HDI and 5.0 % for those born in a country with a low or a medium HDI).

Almost 1 in 4 people born in a country with a low or a medium HDI (23.1 %) migrated because they were looking for asylum or international protection compared with 8.0 % for people from a country with a high or a very high HDI and 2.4 % from another EU country.

Migrating for international protection or asylum was also more common among men than among women: 37.3 % of men against 24.7 % of women aged 15-29 from a country with a low or a medium HDI migrated for asylum or international protection. Such a difference is also visible for people aged 30-54 (24.6 % against 17.4 %) and aged 55-74 (19.9 % against 15.4 %).

In 2021, more women than men born abroad migrated for family reasons. This is true for all age groups and for all categories of country of birth.

Finally, people aged 30-54 migrated more often for work without having found a job before than the other age groups, and this reason was more common among men than among women.

Figure 7 presents the reason for migrating for the whole foreign-born population by host EU countries. The rationales for which people migrated change also drastically from one country to another.

More than 60 % of foreign-born people migrated for family reasons in Slovakia (74.9 %), Lithuania (69.4 %), Bulgaria (66.4 %), Latvia (64.2 %) and Portugal (62.8 %). More than one quarter of people born in another country migrated for employment without having found a job before migrating in Italy (39.4 %), Greece (34.9 %), Luxembourg (26.9 %) and Spain (26.3 %). In the same way, more than one quarter of the people born in another country migrated for employment and had already found a job before migrating in Malta (33.5 %), Luxembourg (28.1 %) and Cyprus (26.1 %). Furthermore, more than one fifth migrated looking for asylum or international protection in Sweden (28.4 %), Luxembourg (22.9 %) and Croatia (21.4 %). The highest shares of people born outside the reporting country who migrated for education reason were found in France, Latvia, Finland and Ireland, all between 9.5 % and 10.6 %. Finally, Luxembourg, Cyprus and Spain recorded the highest shares of foreign-born people who had migrated for retiring (14.2 %, 1.6 % and 1.5 %).

Duration for finding a job

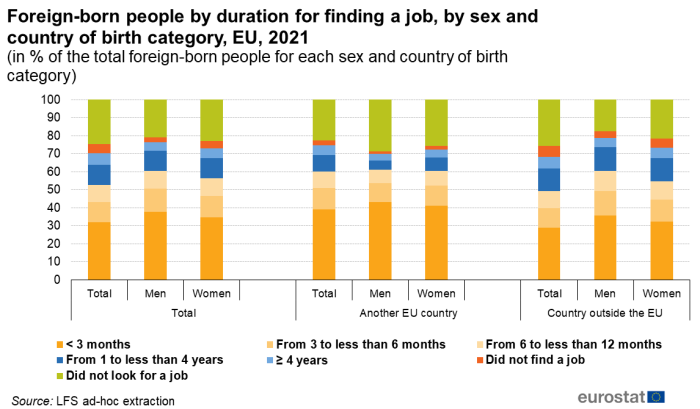

In the EU, almost one third of foreign-born people aged 15-74 (34.8 %) found a job in less than 3 months, 11.9 % in a period from 3 to 6 months, 9.6 % in a period from 6 months to less than 1 year, 11.3 % after 1 year but in less than 4 years and 5.5 % after 4 years or more. To complete the picture, 4.1 % did not find a job and 22.8 % did not look for a job. Looking at Figure 7, women and men show quite large differences. Firstly, 60.5 % of foreign-born men found a job within 1 year against 52.5 % of foreign-born women. Furthermore, 17.7 % of women took more than 1 year to find a job against 15.7 % of men and, 3.0 % of men did not find a job against 5.1 % of women. Moreover, 20.7 % of men born in another country did not look for a job (because they had already found a job before or for other reasons) against 24.6 % of women.

The country of birth seems to play a crucial role in finding a job in a relative short period. 71.3 % of men born in another EU country and 82.5 % of men born in a country outside the EU looked for a job. Among women, this is the opposite 77.4 % of women from another EU country looked for a job against 74.5 % for women born in a non-EU country.

Moreover, considering only those who looked for a job, 85.6 % of men and 77.6 % of women born in another EU country found a job in less than 1 year while this share dropped to 73.2 % and 66.1 % among men and women who were born outside the EU.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing quarterly and annual results on labour market characteristics of people aged 15-89.

The EU-LFS covers the resident population, defined as all people usually residing in private households.

‘Usual residence’ means the place where a person normally spends the daily period of rest, regardless of temporary absences for purposes of recreation, holidays, visits to friends and relatives, business, medical treatment or religious pilgrimage. The following persons alone are considered to be usual residents of a specific geographical area: (a) those who have lived in their place of usual residence for a continuous period of at least 12 months before the reference time; or (b) those who arrived in their place of usual residence during the 12 months before the reference time with the intention of staying there for at least one year.

Where the circumstances described in point (a) or (b) cannot be established, ‘usual residence’ can be taken to mean the place of legal or registered residence.

The concept of migration used in this article refers to people residing in a EU Member State and born in another country (inside or outside the EU). It consequently excludes people coming back to their country of birth after having resided in another country for at least 12 months.

Since 1999, an inherent part of EU-LFS has been the modules. These were called ‘ad hoc modules’ until 2020. From 2021 onwards, they are called either ‘regular modules’ when the variables have an 8-yearly periodicity or ‘modules on an ad hoc subject’ for variables not included in the regular datasets. In 2021, EU-LFS included a module on the labour market situation of migrants and their immediate descendants. From that year onwards, this module will be conducted regularly every eight years under Regulation (EU) 2019/1700.

For further information on the EU-LFS modules, please refer to the article on this subject.

Coverage: The 2021 EU-LFS module on the labour market situation of migrants and their immediate descendants covers all European Union Member States and the EFTA Member States Norway and Switzerland. For Cyprus, the survey covers only the areas of Cyprus controlled by the Government of the Republic of Cyprus.

European aggregates: EU and EU-27 refer to the sum of the 27 EU Member States. If data are unavailable for a country, the calculation of the corresponding aggregates takes into account the data for the same country for the most recent period available. Such cases are indicated.

Country note In Portugal, the age group is from 16 to 74. As in Portugal the reference age of the active population starts at 16 years old, the target population of the 2021 EU-LFS module was adapted to be 16 to 74.

Definitions

The concepts and definitions used in the EU-LFS follow the guidelines of the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Employment covers persons living in private households, who during the reference week performed work, even for just one hour, for pay, profit or family gain, or were not at work but had a job or business from which they were temporarily absent, for example because of illness, holidays, industrial dispute or education and training.

Employment can be measured in terms of the number of persons or jobs, in full-time equivalents or in hours worked. All the estimates presented in this article use the number of persons; the information presented for employment rates is also built on estimates for the number of persons. Employment statistics are frequently reported as employment rates to discount the changing size of countries’ populations over time and to facilitate comparisons between countries of different sizes. These rates are typically published for the working age population, which is generally considered to be those aged between 15 and 64 years. The 15 to 64 years age range is also a standard used by other international statistical organisations (although the age range of 20 to 64 years is given increasing prominence by some policymakers as a rising share of the EU population continue their studies into tertiary education).

The LFS employment concept differs from national accounts domestic employment, as the latter sets no limit on age or type of household, and also includes the non-resident population contributing to GDP and conscripts in military or community service.

The level of education refers to the educational attainment level, i.e. the highest level of education successfully completed. Low level of education refers to ISCED levels 0-2 (less than primary, primary and lower secondary education), medium level refers to ISCD levels 3 and 4 (upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education) and high level of education refers to ISCED levels 5-8 (tertiary education).

Context

The continued development and integration of EU migration policy remains a priority in order to meet the challenges and harness the opportunities that migration represents globally. The integration of nationals of non-member countries legally living in the EU Member States has gained increasing importance in the EU agenda in recent years.

There is a strong link between integration and migration policies since successful integration is necessary for maximising the economic and social benefits of immigration for individuals as well as societies. EU legislation provides a common legal framework regarding the conditions of entry and stay and a common set of rights for certain categories of migrants. More information on the policies and legislation in force in this area can be found in an introductory article on migrant integration statistics.

The Temporary Protection Directive, which was adopted following the conflicts in former Yugoslavia, was triggered for the first time by the Council in response to the unprecedented Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 to offer quick and effective assistance to people fleeing the war in Ukraine.

Indeed, Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine has created a situation of mass arrivals of displaced people from Ukraine unable to return to their homes. Due to the scale of estimated arrivals, the European Commission identified a clear risk that the asylum systems of EU countries would be unable to process applications within the deadlines set. This would negatively affect the efficiency of national asylum processes and adversely affect the rights of people applying for international protection. Following the call of the home affairs ministers, on 2 March 2022, the Commission rapidly proposed to activate the Temporary Protection Directive and, on 4 March 2022, the Council unanimously adopted the Decision giving those fleeing war in Ukraine the right to temporary protection.

This right to temporary protection is associated with facilities offered in relation to access to employment, participation in language courses in the host country language as well as recognition of qualifications obtained abroad. Obstacles to enter the EU labour market should be minimised as much as possible to facilitate the successful integration of migrants into society in the host country.

In this context, the EU-LFS 8-yearly regular module on the labour market situation of migrants and their immediate descendants implemented in 2021 can bring crucial information on the labour market integration and level of skills and qualification of the migrants as well as on obstacles that migrants can face on the EU labour market. This could help EU policy-makers in adjusting their migration and integration policies.

Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine certainly changes the EU migration picture in 2022 compared to 2021. Nevertheless, the objectives of this publication are to give an insight into the potential integration of Ukrainian refugees in the EU labour market and to emphasize the role of other factors than the country of birth, such as the educational attainment level, to properly analyse the employment rates of the migrant population in the EU.

Direct access to

- Main obstacles for foreign-born people to enter the labour market

- Employment - annual statistics

- Unemployment statistics and beyond

- Labour market slack - employment supply and demand mismatch

- All articles on employment

- Migrant integration statistics — online publication

- Foreign-born people and their descendants

- Migration and migrant population statistics

- Labour force survey in the EU, EFTA and candidate countries — Main characteristics of national surveys, 2020, 2022 edition

- Quality report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2020, 2022 edition

- EU labour force survey — online publication

- Migrant integration statistics — online publication

- Foreign-born people and their descendants — online publication

- LFS main indicators (t_lfsi)

- Population, activity and inactivity - LFS adjusted series (t_lfsi_act)

- Employment - LFS adjusted series (t_lfsi_emp)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (t_une)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (t_lfsa)

- LFS series - Specific topics (t_lfst)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Employment and activity - LFS adjusted series (lfsi_emp)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- Labour market transitions - LFS longitudinal data (lfsi_long)

- LFS series - Detailed quarterly survey results (from 1998 onwards) (lfsq)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- LFS series - Specific topics (lfst)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (lfso)

Publications

- Labour force survey in the EU, EFTA and candidate countries — Main characteristics of national surveys, 2020, 2022 edition

- Quality report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2020, 2022 edition

- EU labour force survey — online publication

ESMS metadata files and EU-LFS methodology

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (ESMS metadata file — employ_esms)

- LFS main indicators (ESMS metadata file — lfsi_esms)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (ESMS metadata file — lfsa_esms)

- LFS series - detailed quarterly survey results (from 1998 onwards) (ESMS metadata file — lfsq_esms)

- LFS regional series (ESMS metadata file — reg_lmk)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (ESMS metadata file — lfso_esms)