Archive:Income poverty statistics

Data extracted in May 2020.

Planned article update: June 2021.

This Statistics Explained article has been archived on 3 May 2021, for updated data see Living conditions in Europe - income distribution and income inequality.

Highlights

The at-risk-of-poverty rate (after social transfers) in the EU-27 was 16.8 % in 2018, almost unchanged compared with 2017 (16.9 %).

In 2018, social transfers lifted 8.2 % of the EU-27’s population above the poverty threshold.

The 20 % of the population with the highest disposable income in the EU-27 in 2018 received 5.1 times as much income as the 20 % with the lowest disposable income.

At-risk-of-poverty rate, 2018

This article analyses recent statistics on monetary poverty and income inequalities in the European Union (EU). Comparisons of standards of living between countries are frequently based on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, which presents in monetary terms a basic measure of the overall size of an economy divided by the number of people living there, used to measure national wealth and prosperity. However, this headline indicator does not provide information on the distribution of income within a country and also fails to provide information in relation to non-monetary factors that may play a significant role in determining the well-being of the population.

Full article

At-risk-of-poverty rate and threshold

The at-risk-of-poverty rate (after social transfers) in the EU-27 increased between 2010 (start of the time series) and 2011, from 16.5 % to 16.9 %. This rate was relatively stable for the next two years, before increasing more substantially in 2014 to reach 17.3 %. Smaller increases were observed in 2015 and 2016 (up 0.1 percentage points each year). In 2017, the first notable decrease was observed, the rate dropped to 16.9 % which was followed in 2018 by a further modest reduction of 0.1 points. As such, in the last two years for which data are available the EU-27’s at-risk-of-poverty rate had returned to a level similar to that observed between 2011 and 2013.

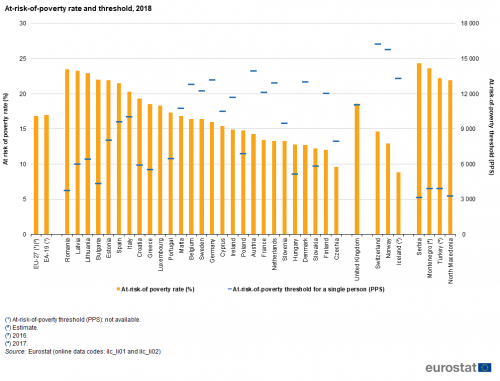

The rate for the EU-27, calculated as a weighted average of national results, conceals considerable variations across the EU Member States (see Figure 1). In seven Member States, namely Romania (23.5 %), Latvia (23.3 %), Lithuania (22.9 %), Bulgaria (22.0 %), Estonia (21.9 %), Spain (21.5 %) and Italy (20.3 %), one fifth or more of the population was viewed as being at risk of poverty in 2018; this was also the case in Serbia (24.3 %), Montenegro (23.6 %; 2017 data), Turkey ( 22.2 %; 2017 data) and North Macedonia (21.9 %). Among the Member States, the lowest proportions of persons at risk of poverty were observed in Czechia (9.6 %), Finland (12.0 %) and Slovakia (12.2 %), while Iceland (8.8 %; 2016 data) reported an even lower share of its population as being at risk of poverty.

The at-risk-of-poverty threshold (also shown in Figure 1) is set at 60 % of national median equivalised disposable income. For cross-country comparisons, it is often expressed in purchasing power standards (PPS), in order to take account of the differences in the cost of living across countries. The income values for this threshold varied considerably among the EU Member States in 2018, ranging from PPS 3 767 in Romania to PPS 13 923 in Austria, with the threshold value in Luxembourg (PPS 19 295) clearly above the top of this range. The poverty threshold was also relatively low in Serbia (PPS 3 136), North Macedonia (PPS 3 298), Montenegro (PPS 3 906; 2017 data) and Turkey (PPS 3 916; 2017 data) and relatively high in Norway (PPS 15 780) and Switzerland (PPS 16 240).

Different subpopulations are more or less affected by monetary poverty

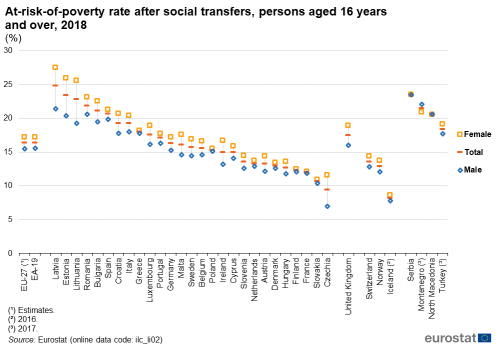

In 2018, there was a small difference in the EU-27 at-risk-of-poverty rate (after social transfers) between the two sexes, with the latest rates for persons aged 16 years and over equivalent to 15.5 % for males, compared with a higher figure of 17.2 % for females. All of the EU Member States, the United Kingdom, the three EFTA countries shown in Figure 2 and Turkey reported higher rates for females than for males among the population aged 16 years and over. The largest gender differences in 2018 were observed in Lithuania (6.3 percentage points higher for females than for males), Latvia (6.1 percentage points), Estonia (5.5 percentage points) and Czechia (4.6 percentage points). Ireland, Malta and Bulgaria reported at-risk-of-poverty rates for females that were at least 3.0 percentage points higher than for their male counterparts. The narrowest gender gap was in France where the at-risk-of-poverty rate was marginally (0.2 percentage points) higher for females than for males. By contrast, in Montenegro the rate was 1.2 percentage points (2017 data) higher for males than for females, while in North Macedonia the rate for males was also higher but only by 0.1 percentage points; in Serbia there was no difference between the rates for the two sexes.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_li02)

The differences in at-risk-of-poverty rates were wider when the population was classified according to activity status

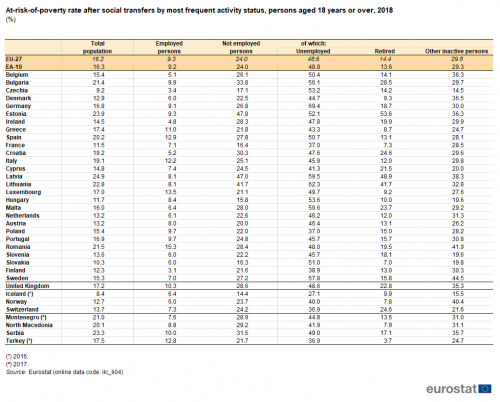

Concerning the risk of poverty, the unemployed are a particularly vulnerable group (see Table 1): almost half (48.6 %) of all unemployed persons in the EU-27 were at risk of poverty in 2018, with by far the highest rate in Germany (69.4 %). A further 11 EU Member States (Lithuania, Malta, Latvia, Sweden, Bulgaria, Hungary, Czechia, Estonia, Slovakia, Spain and Belgium) reported that at least half of the unemployed were at risk of poverty in 2018.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_li04)

Around one in seven (14.4 %) retired persons in the EU-27 were at risk of poverty in 2018. In Estonia (53.6 %), Latvia (48.9 %) and Lithuania (41.7 %), the risk of poverty among retired persons was relatively high, respectively some 3.7, 3.4 and 2.9 times as high as the EU-27 average, while the next highest rate was 28.5 % in Bulgaria.

People in employment were far less likely to be at risk of poverty: the average rate across the whole of the EU-27 in 2018 was 9.3 %. There was a relatively high proportion of employed persons at risk of poverty in Romania (15.3 %) and, to a lesser extent, in Luxembourg (13.5 %) and Spain (12.9 %), while Italy and Greece also reported that more than 1 in 10 members of their respective employed workforce were at risk of poverty in 2018. At-risk-of-poverty rates for employed persons were also at least 10.0 % in Serbia, the United Kingdom and Turkey (2017 data).

At-risk-of-poverty rates are not uniformly distributed between households with different compositions of adults and dependent children

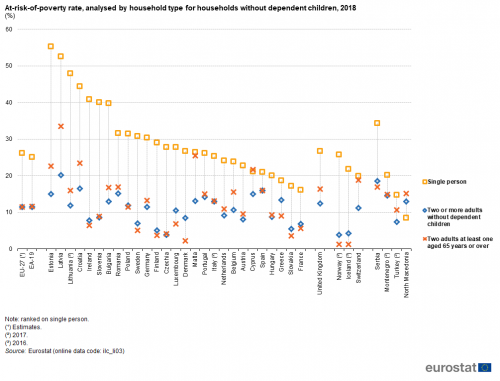

Among households without dependent children (see Figure 3), people living alone were most likely to be at risk of poverty, a situation faced by 26.1 % of single person households in the EU-27 in 2018. By contrast, the at-risk-of-poverty rate for households with two or more adults was less than half this rate, at 11.4 %, which was the same rate for two adult households where at least one person was aged 65 years or over.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_li03)

The vast majority of EU Member States reported a similar pattern: in 2018, single person households had the highest at-risk-of-poverty rates among households without dependent children in all EU Member States except in Cyprus, where two adult households where at least one person was aged 65 years or over had a higher rate (21.7 % compared with 21.1 % for single person households). A similar situation was observed in North Macedonia except that single person households reported the lowest rate (8.5 %) among the three types of households analysed.

In 9 out of 27 EU Member States, the at-risk-of-poverty rate for two adult households with at least one person aged 65 years or over was lower than the rate for the broader category of all households with two or more adults, most notably in Denmark where the difference was 6.2 percentage points. At the other extreme, in Latvia, the at-risk-of-poverty rate for two adult households where at least one person was aged 65 years or over was 13.3 percentage points higher than for all households with two or more adults, while the difference in Malta was 12.4 percentage points. In Spain the rate for both of these types of households was the same, while in Italy the difference was just 0.1 percentage points (2017 data).

Among the households with dependent children, the highest at-risk-of-poverty rate in the EU-27 was recorded for single persons with dependent children, at more than one third (34.2 %)

Looking at the rates for households with two adults, those with just one dependent child (12.1 %) had a risk of poverty that was just under half that recorded for households with three or more dependent children (24.5 %) — see Figure 4.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_li03)

Among the three household types shown in Figure 4, all EU Member States reported that households composed of two adults with one dependent child were the least likely to be at risk of poverty. Most EU Member States reported that the at-risk-of-poverty rate was highest for single persons with dependent children. Nevertheless, there were four exceptions: in Portugal the rate for households composed of a single person with dependent children was 3.3 percentage points lower than that for households with two adults and three or more dependent children, while in Romania and Bulgaria this difference was much larger, 11.8 and 21.2 percentage points respectively; in Slovakia the rate for households composed of a single person with dependent children was the same as that for households with two adults and three or more dependent children. In all four of the candidate countries for which data are available the rate for households composed of a single person with dependent children was lower than that for households with two adults and three or more dependent children.

Social protection measures can be used as a means for reducing poverty and social exclusion

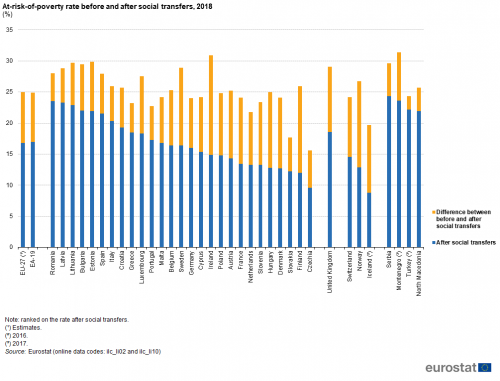

This may be achieved, for example, through the distribution of benefits. One way of evaluating the impact of social protection measures is to compare at-risk-of-poverty indicators before and after social transfers (see Figure 5). In 2018, social transfers reduced the at-risk-of-poverty rate among the population of the EU-27 from 25.0 % before transfers to 16.8 % after transfers, thereby lifting 8.2 % of the population above the poverty threshold. Without social transfers, these people would be at risk of poverty.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_li02) and (ilc_li10)

Comparing at-risk-of-poverty rates before and after social transfers, the impact of social benefits was low — moving at most 6.0 % of people above the poverty threshold — in Czechia (6.0 %), Italy (5.6 %), Latvia, Slovakia (both 5.5 %), Portugal (5.4 %), Greece (4.7 %) and Romania (4.5 %). This was also the case in Serbia (5.3 %), North Macedonia (3.8 %) and Turkey (2.1 %; 2017 data).

Looking at the impact in relative terms, half or more of all persons who were at-risk-of-poverty in Finland and Ireland moved above the threshold as a result of social transfers, as was also the case in Iceland (2016 data) and Norway.

Income inequalities

Governments, policymakers and society in general cannot combat poverty and social exclusion without analysing inequalities within society, whether they are economic or social in nature.

Figure 6 provides information on inequalities in the distribution of income in 2018: a population-weighted average of national figures for the individual EU Member States shows that the 20 % of the population with the highest equivalised disposable income received 5.1 times as much income as the 20 % with the lowest equivalised disposable income in the EU-27. This ratio varied considerably across the Member States, from 3.0 in Slovakia to 6.0 or more in Spain, Italy and Latvia and more than 7.0 in Lithuania, Romania and Bulgaria, where it peaked at 7.7. Among the non-member countries shown in Figure 6, North Macedonia (6.2) and Montenegro (7.6; 2017 data) reported similarly high ratios for the inequality of income distribution, while in Serbia (8.6) and Turkey (8.7; 2017 data) the ratios were higher than in any of the Member States.

Source: Eurostat (ilc_di11)

There is policy interest in the inequalities for subpopulations. One group of particular interest is that of the elderly, in part reflecting the growing proportion of the EU’s population that is aged 65 years and over. Pension systems can play an important role in addressing poverty among the elderly. In this respect, it is revealing to compare the incomes of the elderly with the rest of the population.

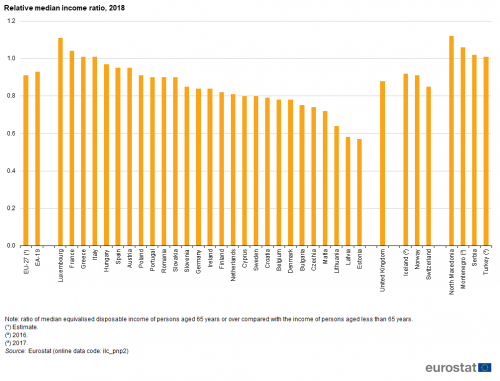

Across the EU-27 as a whole, people aged 65 years or over had a median income in 2018 which was equal to 91 % of the median income for the population under the age of 65 years

In four EU Member States (Luxembourg, France, Greece and Italy), the median income of people aged 65 years and over was higher than the median income of persons under the age of 65 years (see Figure 7). This was also the case in the four candidate countries shown in the figure. In Hungary, Spain, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Slovakia, the median income of people aged 65 years or more was 90 % to 100 % of that recorded for people under the age of 65 years. This was also the case in Iceland (2016 data) and Norway. Ratios below 80 % were recorded in Croatia, Belgium, Denmark, Bulgaria, Czechia, Malta and the Baltic Member States; the lowest rates were 64 %, 58 % and 57 % in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia respectively. Relatively low ratios may broadly reflect relatively low pension entitlements.

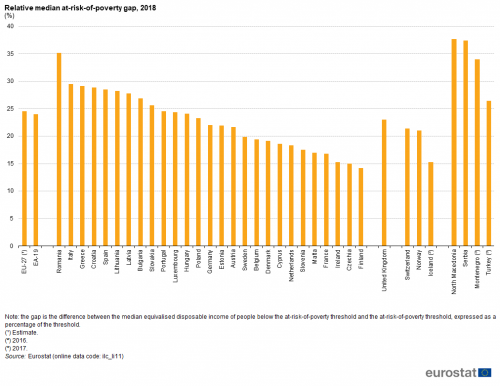

The depth of poverty, which helps to quantify just how poor the poor are, can be measured by the relative median at-risk-of-poverty gap. The median income of persons at risk of poverty in the EU-27 was, on average, 24.5 % below the poverty threshold in 2018 (see Figure 8). This threshold is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income of all persons.

Among the EU Member States, the median income of persons at risk of poverty was furthest below the poverty threshold in Romania (35.2 %). Gaps in excess of 25.0 % were also reported for Italy, Greece, Croatia, Spain, Lithuania, Latvia, Bulgaria and Slovakia. The gaps in North Macedonia (37.7 %) and Serbia (37.4 %) were higher than in any of the Member States and the gaps were also relatively high in Montenegro (34.0 %) and Turkey (26.4 %; 2017 data). The lowest at-risk-of-poverty gap among the EU Member States was observed in Finland (14.2 %), followed by Czechia (15.0 %) and Ireland (15.3 %). The gap in Iceland was also at a similarly low level (15.3 %; 2016 data).

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The data used in this article are primarily derived from micro data from EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). EU-SILC data are compiled annually and are the main source of statistics that measure income and living conditions in Europe; it is also the main source of information used to link different aspects relating to the quality of life of households and individuals. The reference population for the information presented in this article is all private households and their current members residing in the territory of an EU Member State at the time of data collection; persons living in collective households and in institutions are generally excluded from the target population. The data for the EU and the euro area are population-weighted averages of national data.

Household disposable income is established by summing up all monetary incomes received from any source by each member of the household (including income from work, investment and social benefits) — plus income received at the household level — and deducting taxes and social contributions paid. In order to reflect differences in household size and composition, this total is divided by the number of ‘equivalent adults’ using a standard (equivalence) scale, the so-called ‘modified OECD’ scale, which attributes a weight of 1.0 to the first adult in the household, a weight of 0.5 to each subsequent member of the household aged 14 and over, and a weight of 0.3 to household members aged less than 14. The resulting figure is called equivalised disposable income and is attributed to each member of the household. For the purpose of poverty indicators, the equivalised disposable income is calculated from the total disposable income of each household divided by the equivalised household size; consequently, each person in the household is considered to have the same equivalised income.

The income reference period is a fixed 12-month period (such as the previous calendar or tax year) for all countries, except the United Kingdom for which the income reference period is the current year of the survey and Ireland for which the survey is continuous and income is collected for the 12 months prior to the survey.

The at-risk-of-poverty rate is defined as the share of people with an equivalised disposable income that is below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold, set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income. In line with decisions of the European Council, the at-risk-of poverty rate is measured relative to the situation in each EU Member State, rather than applying a common threshold value. The at-risk-of-poverty rate may be expressed before or after social transfers, with the difference measuring the hypothetical impact of national social transfers in reducing the risk of poverty. Retirement and survivors’ pensions are counted as income before transfers and not as social transfers. Various breakdowns of this indicator are available, for example: by age, sex, activity status, household type, or level of educational attainment. It should be noted that the indicator does not measure wealth but is instead a relative measure of low current income (in comparison with other people in the same country).

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value. |

Context

At the Laeken European Council in December 2001, European heads of state and government endorsed a first set of common statistical indicators for social exclusion and poverty that are subject to a continuing process of refinement by the indicators sub-group of the social protection committee. These indicators are an essential element in the open method of coordination to monitor the progress made by the EU’s Member States in alleviating poverty and social exclusion.

EU-SILC is the reference source for EU statistics on income and living conditions and, in particular, for indicators concerning social inclusion. In the context of the EU 2020 strategy, the European Council adopted in June 2010 a headline target for social inclusion that, by 2020, there should be at least 20 million fewer people in the EU at risk of poverty or social exclusion than there were in 2008. EU-SILC is the source used to monitor progress towards this headline target, which is measured through an indicator that combines the at-risk-of-poverty rate, the severe material deprivation rate, and the proportion of people living in households with very low work intensity — see the article on people at risk of poverty or social exclusion for more information.

Direct access to

Living conditions in Europe

- Living conditions in Europe — income distribution and income inequality

- Living conditions in Europe — poverty and social exclusion

Population sub-groups

Statistical books

- Ageing Europe — 2019 edition

- Living conditions in Europe — 2018 edition

- Monitoring social inclusion in Europe — 2017 edition

News releases

- Downward trend in the share of persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU

- Can you afford to heat your home?

- Young people in work and at risk of poverty

- 1 in 7 pensioners at risk of poverty in the EU

- Can you afford a car?

- EU — One in three people unable to face unexpected financial expenses

- How much do social transfers reduce poverty?

- At risk of poverty visualised

- Young people living with their parents

- 1 in 4 young people in overcrowded households

- At-risk-of-poverty thresholds - EU-SILC survey

- At-risk-of-poverty rate by poverty threshold, age and sex - EU-SILC survey

- At-risk-of-poverty rate by poverty threshold and most frequent activity in the previous year - EU-SILC survey

- At-risk-of-poverty rate before social transfers (pensions included in social transfers) by poverty threshold, age and sex - EU-SILC survey

- At-risk-of-poverty rate before social transfers (pensions excluded from social transfers) by poverty threshold, age and sex - EU-SILC survey

- Relative at risk of poverty gap by poverty threshold - EU-SILC survey

- S80/S20 income quintile share ratio by sex and selected age group - EU-SILC survey

- Relative median income ratio (65+) - EU-SILC survey

General methodological information

- EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) methodology

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

- Income and living conditions dataset — description

Detailed papers

- Comparative EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions: Issues and Challenges (Proceedings of the International Conference on EU Comparative Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, Helsinki, 6–8 November 2006)

- How does attrition affect estimates of persistent poverty rates? The case of European Union statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Individual employment, household employment and risk of poverty in the EU — A decomposition analysis — 2013 edition

- Statistical matching of EU-SILC and the Household Budget Survey to compare poverty estimates using income, expenditures and material deprivation — 2013 edition

- Using EUROMOD to nowcast poverty risk in the European Union — 2013 edition

- Regulation (EC) No 1177/2003 of 16 June 2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation (EC) No 1553/2005 of 7 September 2005 amending Regulation 1177/2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation 1589/2015 of 13 July 2015 laying down detailed rules for the application of Article 108 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- Summaries of EU Legislation: EU statistics on income and living conditions

- Summaries of EU Legislation: State aid procedural rules

Employment and social analysis, see:

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion — Employment and Social Developments in Europe — Quarterly Review — December 2019

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion — Employment and Social Developments in Europe — Annual Review 2019

- OECD — Better Life Initiative: Measuring Well-being and Progress

- The European Social Survey