Archive:Household accounts at regional level

This Statistics Explained article is outdated and has been archived - for recent articles on national accounts and GDP see here.

- Data from March 2011. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database.

One of the primary aims of regional statistics is to measure the wealth of regions. This is of particular relevance as a basis for policy measures which aim to provide support for less well-off regions.

The indicator most frequently used to measure the wealth of a region is regional gross domestic product (GDP), usually expressed in purchasing power standard (PPS) per inhabitant to make the data comparable between regions of differing size and purchasing power.

GDP is the total value of goods and services produced in a region by the people employed in that region, minus the necessary inputs. However, owing to a multitude of interregional flows and state interventions, the GDP generated in a given region often does not tally with the income actually available to the inhabitants of the region. This article takes a look at household incomes in the regions of the European Union (EU) and how much of this is available after income distribution mechanisms have had an effect.

Main statistical findings

Private household income

In market economies with state redistribution mechanisms, a distinction is made between two stages of income distribution. The primary distribution of income shows the income of private households generated directly from market transactions, i.e. the purchase and sale of factors of production and goods.

These include in particular the compensation of employees, i.e. income from the sale of labour as a factor of production. Private households can also receive income on assets, particularly interest, dividends from equity shares and rents. Then there is income from operating surpluses and self-employment. Interest and rents payable are recorded as negative items for households in the initial distribution stage. The balance of all these transactions is known as the primary income of private households.

Primary income is the point of departure for the secondary distribution of income, which means the state redistribution mechanism. All social benefits and transfers other than in kind (i.e. monetary transfers) are now added to primary income. From their income, households have to pay tax on income and wealth, pay their social contributions and effect transfers. The balance remaining after these transactions have been carried out is called the disposable income of private households.

For an analysis of household income, a decision must first be made about the unit in which data are to be expressed if comparisons between regions are to be meaningful.

For the purposes of making comparisons between regions, regional GDP is generally expressed in PPS, so that meaningful volume comparisons can be made. The same process should therefore be applied to the income parameters of private households. These are converted using specific purchasing power standards for final consumption expenditure, called purchasing power consumption standards (PPCS).

Results for 2008

Primary income

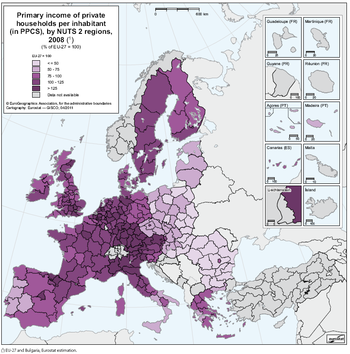

Map 1 gives an overview of primary income in the NUTS 2 regions of the 24 countries examined here. Centres of wealth are clearly evident in southern England, northeastern Scotland, Paris, northern Italy, Austria, Madrid and north-eastern Spain, Vlaams Gewest (Belgium), the western Netherlands, Stockholm (Sweden) and Nordrhein- Westfalen, Hamburg and its surroundings, Hessen, Baden-Wurttemberg and Bayern (Germany). Also, there is a clear north–south divide in Italy and a west–east divide in Germany, whereas in France income distribution is relatively uniform between regions. The United Kingdom, too, has a north–south divide, albeit less marked than the divides in Italy and Germany.

In the new Member States, most of the regions with relatively high primary incomes are capital regions, in particular Bratislava in Slovakia (112 % of the EU-27 average) and Praha in the Czech Republic (95 %). Zahodna Slovenija and Vzhodna Slovenija (Slovenia) and Bucureşti - Ilfov (Romania) also have primary incomes higher than 75 % of the EU average. All the regions of the Czech Republic, apart from Praha, and 15 other regions in the new Member States have primary incomes of private households between 50 % and 75 % of the EU average. The figure is below 50 % in the remaining regions of the new Member States.

The regional values range from 3 600 PPCS per inhabitant in Severozapaden (Bulgaria) to 35 900 PPCS in the UK region of Inner London. The 10 regions with the highest income per inhabitant include four regions in Germany, three in the UK and one each in Belgium, France and Sweden. This concentration of regions with the highest incomes in the United Kingdom and Germany is also evident when the ranking is extended to the top 30 regions: this group contains 11 German and six UK regions, along with three regions each in Belgium, Italy and Austria, two in the Netherlands, and one each in France and Sweden.

It is no surprise that the 30 regions at the tail end of the ranking are all located in the new Member States; they comprise 12 of the 16 Polish regions, all six Bulgarian regions, seven of the eight Romanian regions, four Hungarian regions and one Slovakian region. In 2008, the highest and lowest primary incomes in the EU regions differed by a factor of 9.8. Seven years earlier, in 2000, this factor had been 14.3. It follows that the gap between the opposite ends of the distribution narrowed considerably over the period 2000–08. This positive development can be attributed partly to the Romanian and Bulgarian economies catching up on the rest of the EU.

Disposable income

A comparison of primary income with disposable income shows the levelling influence of state intervention. More especially, this increases the relative income level in some regions of Italy and Spain, in the west of the United Kingdom and in parts of eastern Germany. Similar effects can be observed in the new Member States, particularly in Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Poland. However, the levelling-out of private income levels in the new Member States is generally less pronounced than in the EU-15 Member States.

Despite state redistribution and other transfers, most capital regions maintain their prominent position as having the highest disposable incomes in their respective countries. The regional values range from 3 800 PPCS per inhabitant in Severozapaden (Bulgaria) to 26 100 PPCS in the UK region of Inner London. Of the 10 regions with the highest perinhabitant disposable income, four each are in the UK and in Germany, and one each in Spain and France.

The region with the highest disposable income in the new Member States is Bratislavský kraj (Slovakia) with 14 600 PPCS per inhabitant (99 % of the EU-27 average), followed by Vzhodna Slovenija (Slovenia) with 13 900 PPCS (94 %) and Praha (Czech Republic) with 13 200 PPCS (90 %).

A clear regional concentration is also evident when the ranking is extended to the top 30 regions: this group contains 13 German and six UK regions, along with three regions each in Austria and Italy, two in Spain and one each in Belgium, Greece and France.

The tail end of the distribution is very similar to the ranking for primary income. The bottom 30 include nine Polish and seven Romanian regions, six regions each in Bulgaria and Hungary, one Slovakian region and Estonia. State activity and other transfers significantly reduce the difference between the highest and lowest regional values in the 24 countries examined here, from a factor of around 9.8 to 6.8.

For disposable income there has been a significant trend towards a narrower spread in regional values over recent years: between 2000 and 2008 the difference between the highest and lowest values fell from a factor of 10.8 to 6.8. For primary and disposable income alike, this positive development is partly the result of the economic catchingup process in Romania and Bulgaria.

To summarise, between 2000 and 2008, there was a clear narrowing of the difference between the highest and lowest regional values for both primary income and disposable income (influenced by state interventions and other transfers).

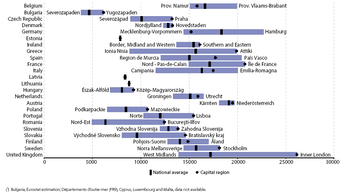

The regional spread in disposable income within the individual countries is obviously much lower than for the EU as a whole, but varies considerably from one country to another. Figure 1 gives an overview of the spread of disposable income per inhabitant between the regions with the highest and the lowest values for each country. We can see that, with a factor of almost 2.5, the regional disparity is greatest in Romania. This means that disposable income per inhabitant in Bucureşti - Ilfov is two and a half times as high as in the Nord-Est region. Greece, the UK and Slovakia also have high regional differences, with factors of between 1.8 and 2.2. In Italy, Spain, Poland, Bulgaria and Germany the highest values are, in each case, between 57 % and 73 % above the lowest.

The regional differences tend to be higher in the new Member States than in the EU-15. Of the new Member States, Slovenia — with 16 % — has the smallest spread between the highest and lowest values and thus comes close to Denmark (8 %) and Austria (9 %), which have the lowest regional income disparities in the entire EU. Ireland, the Netherlands and Sweden also have only moderate regional disparities, with the highest regional values between 17 % and 26 % above the lowest ones. Figure 1 also shows that the capital city regions of 14 of the 21 countries with more than one NUTS 2 region also have the highest income values. All seven new Member States with at least two NUTS 2 regions belong to this group.

The economic dominance of the capital regions is also evident when we compare their income values with the national averages. In three countries (Romania, Slovakia and the United Kingdom), the capital city regions exceed the national values by more than 50 %. Only in Belgium and Germany are the values for the capital lower than the national average.

To assess the economic situation in individual regions, it is important to know not just the levels of primary and disposable income but also their relationship to each other. Map 2 shows this quotient, which gives an idea of the effect of state activity and of other transfer payments. On average, disposable income in the EU-27 amounts to 86.7 % of primary income. The figure was 86.4 % in 2000, so over this eight-year period the scale of state intervention and other transfers has not changed.

The lowest values are to be found in the capital regions and other economic centres of the more affluent Member States, in particular Hovedstaden (Denmark) at 64.8 %, Utrecht (Netherlands) at 67.3 %, Stockholm (Sweden) at 72.7 % and Inner London (UK) at 72.8 %; the highest values are found in the rural Romanian regions Nord-Est at 120.3 %, Sud- Vest Oltenia at 114.3 % and Sud - Muntenia at 111.2 %.

In general, the figures for the EU-15 Member States are lower than for the new Member States. On closer inspection, typical differences can be seen between the regions of the Member States. Disposable income in the capital cities and other prosperous regions of the EU-15 is generally less than 80 % of primary income. Correspondingly higher percentages can be observed in all the Member States in the less affluent areas, in particular on the southern and southwestern peripheries of the EU, in the west of the United Kingdom and in eastern Germany. The reason for this is that, in regions with relatively high income levels, a larger share of primary income is transferred to the state in the form of taxes. At the same time, state social benefits amount to less than in regions with relatively low income levels.

The regional redistribution of wealth is generally less significant in the new Member States than in the EU-15. For the capital regions the values are mostly between 75 % and 85 % and are almost without exception at the bottom end of the ranking within each country. This shows that incomes in these regions require much less support through social benefits than elsewhere. The difference between the capital region and the rest of the country is particularly large in Romania and Slovakia, at around 15 percentage points.

In the 24 EU Member States examined here, disposable income exceeds primary income in a total of 28 regions. These are seven Polish regions, five regions each in Portugal and Romania, four in Greece, three in Bulgaria, two in the UK, and one each in German and Italy. Map 2 clearly shows that these are particularly poor regions of the Member States in question. No clear differences were found in income support for private households between the new Member States and the EU-15 countries. When interpreting these results, however, we should bear in mind that it is not just monetary social benefits from the state which may cause disposable income to exceed primary income. Other transfer payments (e.g. transfers from people temporarily working in other regions) can play a role as well.

Dynamic development on the edges of the EU

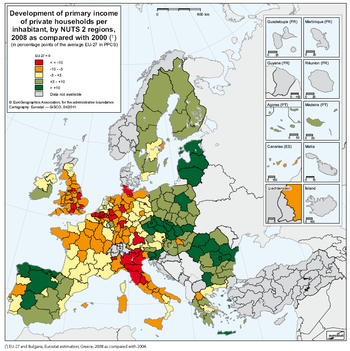

The focus finally turns to an overview of longer-term trends in the regions compared with the EU-27 average. Map 3 uses an eight-year comparison to show how primary income per inhabitant (in PPCS) in the NUTS 2 regions changed between 2000 and 2008 compared to the average for the EU-27.

It shows, first of all, dynamic processes at work at the edges of the EU, particularly in Spain, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania, the Baltic States, Finland and some parts of Greece and Ireland.

On the other hand, incomes have grown at a below-average rate in most of the EU’s founding Member States. Belgium, Germany and Italy have been particularly hard hit; there, incomes fell back considerably, compared to the average, even in some regions which are not particularly prosperous.

The changes range from + 53 percentage points compared to the EU-27 average for Bucureşti - Ilfov (Romania) to – 20 percentage points for Brussels.

Despite overall clear evidence that the new Member States are catching up, the positive trend is not equally strong everywhere. In some regions of Hungary and Poland, disposable incomes only rose by a few percentage points compared to the EU average. Közép-Magyarország (Hungary) was the only region in a new Member State which fell back (by 3 percentage points) compared to the EU average. The figures for Romania and Bulgaria, on the other hand, are very encouraging. Even the Bulgarian region of Severozapaden (with the lowest income in the whole of the EU) caught up by 7.5 percentage points compared to average income in the EU. The structural problem nevertheless remains that, in most of the new Member States, the wealth gap between the capital city and the less prosperous areas of the countries has widened further.

On the whole, the trend between 2000 and 2008 resulted in a slight flattening at the top of the regional income distribution band, caused in particular by substantial relative falls in regions with high levels of income. Over the same period, the 10 regions at the bottom of the scale, all in Bulgaria or Romania, caught up by between 4.4 and 12.0 percentage points compared to the EU average.

Data sources and availability

Eurostat has had regional data on the income categories of private households for a number of years. The data are collected for the purposes of the regional accounts at NUTS level 2.

There are still no data available at NUTS level 2 for the following regions: France’s overseas departments, Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta. For Bulgaria the regional figures for 2008 were estimated using the regional structure from 2007. The same nominal growth rate as for GDP was assumed for the national data.

The text in this statistical article, therefore, relates to only 24 Member States, or 264 NUTS 2 regions. Three of these 24 Member States consist of only one NUTS 2 region, namely Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

Owing to the limited availability of data, the EU-27 values for the regional household accounts had to be estimated. For this purpose, it was assumed that the share of the missing Member States in household income for the EU-27 as a whole was the same as for GDP. For the reference year 2008, this portion was 0.5 %.

Data that reached Eurostat after 25 March 2011 are not taken into account in this statistical article.

Context

One drawback of regional GDP per inhabitant as an indicator of wealth is that a ‘place-of-work’ figure (the GDP produced in the region) is divided by a ‘place-of-residence’ figure (the population living in the region). This inconsistency is of relevance wherever there are net commuter flows — i.e. more or fewer people working in a region than living in it. The most obvious examples are the Inner London region of the UK and Luxembourg, which have by far the highest GDP per inhabitant in the EU. Yet this by no means translates into a correspondingly high income level for the people who live in the region, as thousands of commuters travel to Inner London (UK) and Luxembourg every day to work but live in the neighbouring regions. Hamburg (Germany), Wien (Austria), Praha (Czech Republic) and Bratislavský kraj (Slovakia) are other examples of this phenomenon.

Apart from commuter flows, other factors can also cause the regional distribution of actual income not to correspond to the distribution of GDP. These include income from rent, interest or dividends received by the residents of a certain region, but paid by residents of other regions.

This being the case, a more accurate picture of a region’s economic situation can be obtained only by adding the figures for net income accruing to private households.

See also

- European sector accounts - background

- Household financial assets and liabilities

- National accounts and GDP

- Update of the SNA 1993 and revision of ESA95 (background article)

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Eurostat regional yearbook 2010

- Eurostat regional yearbook 2011 - chapter 8

- Over-indebtedness of European households in 2008 - Statistics in Focus 61/2010

- Regional discrepancies in private household income continue to narrow in 2008 - Statistics in Focus 59/2011

Main tables

- Regional economic accounts - ESA95 (t_reg_eco)

- Disposable income of private households, by NUTS 2 regions (tgs00026)

- Primary income of private households, by NUTS 2 regions (tgs00036)

Database

- Regional economic accounts - ESA95 (reg_eco)

- Household accounts - ESA95 (reg_ecohh)

- Allocation of primary income account of households at NUTS level 2 (nama_r_ehh2p)

- Secondary distribution of income account of households at NUTS level 2 (nama_r_ehh2s)

- Income of households at NUTS level 2 (nama_r_ehh2inc)

- Household accounts - ESA95 (reg_ecohh)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Household accounts - ESA95 (ESMS metadata file - reg_ecohh_esms)