Ageing Europe - statistics on working and moving into retirement

Data extracted in July 2020.

Planned article update: February 2024.

Highlights

The share of people aged 55 years or more in the total number of persons employed in the EU-27 increased from 12 % to 20 % between 2004 and 2019.

In 2019, 48 % of all working men aged 65 years or more in the EU-27 were employed on a part-time basis compared with 60 % of women aged 65 years or more.

Agriculture, forestry and fishing was the largest employer of people aged 65 years or more in the EU-27, employing 14.9 % of the workforce for this age group in 2019.

Ageing Europe — looking at the lives of older people in the EU is a Eurostat publication providing a broad range of statistics that describe the everyday lives of the European Union’s (EU) older generations.

Some older people face a balancing act between their work and family commitments, while financial considerations and health status often play a role when older people consider the optimal date for their retirement.

Many of the EU Member States are increasing their state pension age, with the goal of keeping older people in the workforce for longer and thereby moderating the growth in the overall financial burden of state pensions. The success of such attempts depends, to some degree, on having an appropriate supply of jobs. This may partly help offset the impact of population ageing, while improving the financial well-being of some older people who might not otherwise have an adequate income for their retirement.

Full article

Employment patterns among older people

In 2019, there were 200.0 million persons aged 15 years or more employed [1] across the EU-27; of these, some 40.3 million were aged 55 years or more — with 22.4 million people aged 55-59 years, 12.8 million aged 60-64 years and 5.1 million aged 65 years or more.

The total number of adults (aged 15 years or more) employed in the EU-27 rose overall by 11.1 % during the period from 2004 to 2019. Much higher growth rates were recorded for older people as the number of persons employed and aged 55-64 years increased by 89.8 %, with a similar expansion in the number of persons employed who were aged 65 years or more (up 82.1 %).

People aged 55 years or more accounted for one fifth of the total workforce

The share of people aged 55 years or more in the total number of persons employed in the EU-27 increased from 11.9 % to 20.2 % between 2004 and 2019 (see Figure 1); this development was uninterrupted, as the share rose each year. The number of people employed increased at its fastest pace among people aged 60-64 years, with the total number of employed people in this age group more than doubling (up 139 %); the number of people aged 65-69 years and 55-59 years who were employed also increased at a rapid pace, rising by 99 % and 70 % respectively.

(% of total employment)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egan)

One consequence of increasing longevity is people (having to) work more years before retirement

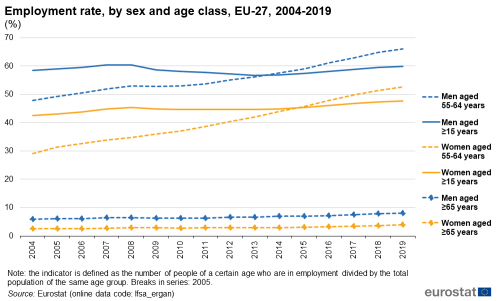

The EU-27 employment rate [2] for adult men (aged 15 years or more) stood at 59.9 % in 2019 while the corresponding rate for women of the same age was 47.7 %; note that this age range includes a high number of people who are still studying (and have yet to start their working lives) as well as a considerable number of retired people (who have already finished their working lives). In 2019, employment rates for men and women aged 55-64 years were higher, at 66.0 % for men and 52.6 % for women, than the average rates for all adult men and women. The most striking aspect of Figure 2 is the rapid pace at which employment rates for people aged 55-64 years increased between 2004 and 2019 (with little or no impact from the global financial and economic crisis); this was particularly notable in relation to the growing proportion of women in work.

Figure 3 confirms this pattern of rising employment rates among people aged 55-64 years: between 2004 and 2019 employment rates for this age group increased in all of the EU Member States. In Slovakia and Austria, the employment rate for people aged 55-64 years more than doubled during the period under consideration. In 2019, employment rates among people aged 55-64 years were more than 70.0 % in Sweden, Germany, Estonia and Denmark, while at the other end of the range there were six EU Member States — Poland, Slovenia, Romania, Croatia, Greece and Luxembourg — where rates for this age group were less than 50.0 %.

One means to try to increase financial security in old-age is to work longer. Older people who delay their retirement earn more money, may accumulate additional pension rights and may be able to save some of the earnings or divert them to a private pension plan. Although low, a growing share of the EU-27 population aged 65-74 years continued to work. In 2019, more than one quarter (27.5 %) of this age group in Estonia were employed, while this rate was also at least 17.0 % in Latvia, Ireland, Sweden, Lithuania and Portugal.

Figure 4 shows employment rates for people aged 65 years or more. Across the EU-27, 8.1 % of men in this age group were employed in 2019, which was slightly more than double the corresponding share recorded among older women (3.9 %). This pattern — a higher employment rate for older men — was repeated in each of the EU Member States (note that data are not available for older women in Luxembourg). The gender gap in employment rates for older people aged 65 years or more peaked at 11.3 percentage points in Cyprus, while Ireland was the only other Member State to record a difference in double-digits.

Across the EU Member States, the highest employment rate for men aged 65 years or more was recorded in Ireland (17.3 %), closely followed by Portugal (17.1 %) and Estonia (16.8 %). The highest employment rate for women aged 65 years or more was recorded in Estonia (12.8 %), followed by Latvia (9.2 %).

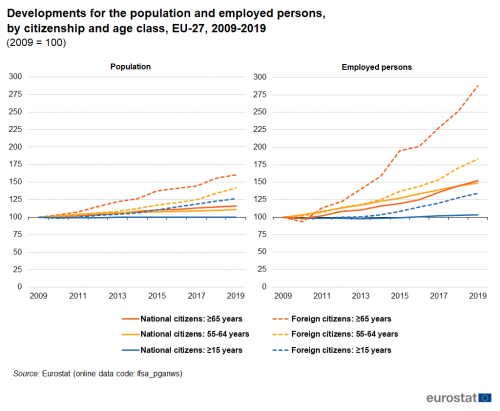

There was particularly rapid growth in the number of older foreign citizens in employment

The first part of Figure 5 presents information showing EU-27 population developments by age and citizenship. During the period from 2009 to 2019, the number of adults (defined here as people aged 15 years or more) who were foreign citizens living in the EU-27 increased at a much more rapid pace (up 26.6 % overall) than the number of national citizens (which was more or less unchanged; down 0.3 % overall). A closer examination reveals that the relative importance of older generations in both national and foreign citizens increased between 2009 and 2019; this was particularly the case for people aged 65 years or more.

The second part of Figure 5 presents similar data but for employment developments. During the period 2009 to 2019, the number of adults employed in the EU-27 rose at a somewhat faster pace than the number of inhabitants both for national and foreign citizens. The number of foreign citizens aged 55-64 years who were employed in the EU-27 rose by 83.3 % overall between 2009 and 2019, while the number of national citizens of the same age who were in employment increased by 48.9 %. Even higher rates of change were recorded among the relatively few people aged 65 years or more who remained in work, as the number of persons employed more than doubled for foreign citizens (up 188.0 %) and increased by 52.5 % for national citizens.

(2009 = 100)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_pganws)

More than half of the workforce aged 65 years or more was employed on a part-time basis

While the information presented so far has highlighted the quite rapid transformation of EU labour markets driven by a growing number of older people in work, policymakers stress the need for these developments to continue. Employers can try to stimulate the supply of older people available for employment by improving working conditions; employees can also try to avoid an abrupt end to their working lives. Increasing numbers of older people are choosing a phased retirement (for example, moving from working full-time to 60 % or 50 % of their normal working hours before moving permanently into retirement), while other older people who do retire may subsequently take on a part-time job or become self-employed or a freelancer.

In 2019, almost one fifth (18.3 %) of the EU-27 workforce aged 15-64 years was employed on a part-time basis, with much higher shares for women (29.9 %) than for men (8.4 %). Figure 6 indicates the extent to which part-time work is common for older people and, in particular, the relatively high rates recorded among those people aged 65 years or more: in 2019, almost half (47.6 %) of all working men in this age group were employed on a part-time basis, while the share for older women was higher still, at 60.2 %. In approximately half (13 out of 27) of the EU Member States, more than 50.0 % of all older people aged 65 years or more who remained in employment were found to be working on a part-time basis, with this share exceeding 75.0 % in Austria and the Netherlands.

More than two fifths of the workforce aged 65-74 years were self-employed

Self-employment can offer the flexibility to help some older people stay in work — for example, professionals such as accountants might become consultants, or teachers become private tutors or supply teachers. Whether by choice or resulting from a lack of other options, many self-employed people appear to retire later in life (or even not at all).

Figure 7 shows that in 2019 some 13.3 % of the EU-27 workforce aged 25-54 years were self-employed. This share was considerably higher for older people: 41.6 % of the workforce aged 65-74 years were self-employed, while this share reached 58.4 % for people aged 75 years or more. The self-employment share among people aged 65-74 years was close to two thirds in Greece, Romania and Portugal; this may be linked in part to a high proportion of this workforce being elderly farmers who continued to work, often on very small, family-based, subsistence farms. More than half of the workforce aged 65-74 years was self-employed in Luxembourg, Belgium, Italy, Finland, Ireland and Spain.

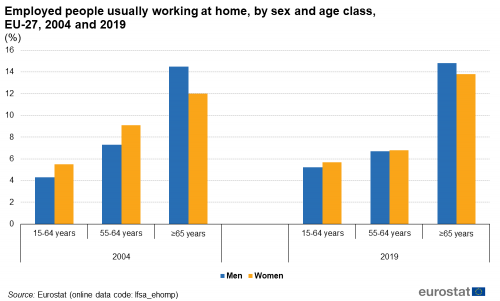

One seventh of the workforce aged 65 years or more usually worked from home

Across the EU-27 in 2019, men and women aged 65 years or more were almost three times as likely to usually work at home as their colleagues aged 15-64 years (see Figure 8); note that these statistics cover the period immediately prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The share of employed men aged 65 years or more usually working at home was 14.8 %, marginally above the corresponding share for older women (13.8 %). Between 2004 and 2019, the share of the EU-27 workforce aged 65 years or more usually working at home (both men and women) increased marginally from 13.6 % to 14.4 %; this pattern was also repeated for the working-age population (defined here as those aged 15-64 years), as their share usually working at home rose from 4.8 % in 2004 to 5.4 % by 2019.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_ehomp)

Focus on common jobs among older people

Agriculture, forestry and fishing was the largest employer of people aged 65 years or more

In 2019, approximately one seventh (14.9 %) of the EU-27 workforce aged 65 years or more — equivalent to some 755 000 people — was employed in agriculture, forestry and fishing. Despite a rapid contraction in their level of employment, these activities continued to be the largest economic activity — based on NACE Sections — in terms of the count of older people (aged 65 years or more) in employment. Figure 9 shows that the EU-27 agriculture, forestry and fishing workforce composed of older people contracted overall by 34.3 % between 2009 and 2019. This was in stark contrast to developments for the other five economic activities presented: for example, the number of older people employed in education and in health and social work more than doubled during the period under consideration.

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egan2)

Figure 10 shows a more detailed picture of the employment situation for the six economic activities — based on NACE Divisions — with the highest numbers of older people (aged 65 years or more) in their respective workforces across the EU-27. In 2019, crop and animal production and hunting (hereafter, agriculture) was the principal employer of older people in the EU-27, particularly among older men (aged 65-74 years). The three activities that followed in the ranking — human health activities; retail trade (except motor trades); education— each employed a higher number of older women (aged 65-74 years) than older men.

Figure 10 also provides information on the number of people who continued to work beyond the age of 75 years. In 2019, there were 97 800 people across the EU-27 aged 75 years or more working in agriculture, while the next largest workforce for this age group was the 49 100 people who worked in retail trade (except motor trades).

(thousands)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egan22d)

In 2019, older people (defined here as those aged 55-74 years) accounted for almost one fifth (19.9 %) of the total number of persons employed in the EU-27. This share (rather than absolute number of workers) peaked, across NACE Divisions, within undifferentiated goods- and services-producing activities of private households for own use — where 31.9 % of the total workforce was found to be aged between 55 and 74 years, closely followed by activities of households as employers of domestic personnel (31.3 %) and agriculture (30.1 %).

Figure 11 shows which economic activities employed the highest shares of older people. In 2019, there were seven EU Member States where agriculture was the leading activity providing work to people aged 55-74 years: in Portugal, more than half (51.7 %) of the total workforce within agriculture was aged 55-74 years. However, there was one EU Member State where employment among older people was even more concentrated. Older people aged 55-74 years accounted for 60.0 % of those employed in creative, arts and entertainment activities in Cyprus.

(% share of total number of persons employed)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egan2) and (lfsa_egan22d)

Duration of work for older people

While employment rates for older people have risen in recent years, this does not necessarily mean their labour input has increased proportionally. Although a greater number of older people are remaining in the workforce for longer, many also reduce their number of hours worked (less hours each day, less days each week, or lengthier holidays).

Employed women aged 65-74 years spent an average of 25.0 hours per week at work

As people become older their average number of usual working hours declines, albeit by a relatively small margin up to the age of 64 years. Figure 12 shows that the largest reduction in average working hours was recorded for older men and women aged 65-74 years (by when a majority of the population had already retired), indicating that this age group was particularly likely to work on a part-time basis, by choice or necessity. In 2019, the number of usual working hours in the EU-27 averaged 30.6 hours per week for older men aged 65-74 years and 25.0 hours per week for older women of the same age.

The average duration of a man’s working life was 4.9 years higher than that of a woman

The duration of working life (as shown in Figure 13) provides a measure of the average number of years for which people aged 15 years are expected to be active in the labour market throughout their lives (under the currently prevailing age-specific participation rates); this information can be used to monitor developments in relation to early retirement.

In 2019, a man aged 15 years in the EU-27 could expect to be part of the labour force for 38.3 years, while the corresponding figure for a woman was 33.4 years; this difference may be largely explained by i) a higher share of women interrupting their careers to support the needs of family life as well as ii) different pension ages for men and women in some EU Member States. Young men in the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Malta, Ireland and Cyprus could expect to work for upwards of 40 years, while Sweden was the only EU Member State where young women could expect to work for this length of time. By contrast, young women in Italy and Greece could expect to be active in the labour market for less than 30 years.

Across the EU-27, the average duration of working life rose for men and for women between 2000 and 2019. The increase in the length of an average woman’s working life was an additional 4.7 years during this period, while that for men was 2.5 years. This pattern of working for longer (additional years) was observed in the vast majority of EU Member States, the only exceptions being Romania (for both sexes) and Greece (for men only).

Policymakers have recognised that job satisfaction plays an important role in relation to active ageing, extending working lives. Alongside remuneration, job satisfaction can be linked to a wide range of other factors, including: working conditions, job security, support and recognition at work, or having the opportunity to learn new skills.

Older people were more likely to be satisfied at work

In 2019, approximately 90 % of the EU-27 working-age population (15-64 years) were satisfied at work. Job satisfaction for older people (aged 65-74 years) was even higher, at 93.0 % for older women and 93.9 % for older men (see Figure 14).

Older people were more likely to agree that a man’s principal role in life is to earn money

Special Eurobarometer 465 provides information on attitudes concerning gender and work (see Figure 15). In June 2017, the share of the EU-27 population who thought that the most important role of a man was to earn money increased with age; some 62 % of the population aged 75 years or more agreed with this premise. Conversely, the share of the EU-27 population who thought that gender equality at work had been achieved fell (marginally) with age; some 42 % of the population aged 75 years or more agreed with this premise.

(% of respondents)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjangroup) and Special Eurobarometer 465 — Gender equality 2017

Accidents at work among older people

Older people, like people in other age groups, suffer from workplace, traffic and domestic accidents. As older people account for a growing share of the EU’s workforce and some very old people continue to work, some employers may face a range of emerging health and safety risks in the workplace.

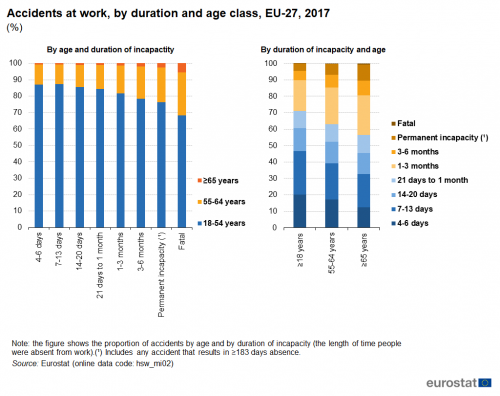

Although older people had fewer accidents at work, they were more likely to be serious or fatal

Figure 16 shows the share of total accidents at work by age and by severity (as measured by the average duration of incapacity). People aged 18-54 years accounted for a majority of the accidents at work in the EU-27, irrespective of the period of incapacity.

As the severity of an accident at work increases, so does the probability that the accident involves an older person. In 2017, the EU-27 workforce aged 55-64 years accounted for 12.1 % of all accidents at work that resulted in between 4 and 6 days of incapacity, while this age group had a 21.3 % share of accidents at work that led to permanent incapacity, and a 26.4 % share of fatal accidents; a similar pattern of increasing shares (but all at a lower level) was observed for people aged 65 years or more.

An alternative picture is presented in the second half of Figure 16: it reveals that in 2017 approximately one quarter (26.5 %) of all accidents at work in the EU-27 resulted in 7-13 days of incapacity. By contrast, approximately one quarter (24.1 %) of all accidents at work among people aged 65 years or more resulted in 1-3 months of incapacity. Older people may be disproportionately affected by accidents at work as a result of various age-related disabilities, such as impaired vision, hearing and mobility (see Chapter 2 for more information).

In 2017, there were 1 801 non-fatal accidents per 100 000 working people in the EU-27 [3]. Older people were less likely to have a non-fatal accident than their younger counterparts: 1 683 per 100 000 working people among those aged 55-64 years and 1 076 per 100 000 working people among those aged 65 years or more. However, as noted above, when older people did experience an accident, it was more likely to be serious or fatal. In 2017, there were 2.3 fatal accidents per 100 000 working people in the EU-27. Older people were more likely to have a fatal accident: 3.6 deaths per 100 000 working people among those aged 55-64 years and 5.1 deaths per 100 000 working people among those aged 65 years or more (see Figure 17). It should be noted that the likelihood of an accident at work, whether fatal or not, is strongly related to the nature of the work. Some economic activities have higher fatal accident rates than others and, as noted earlier, the older workforce tends to be concentrated in certain activities, particularly agriculture which has one of the highest rates in the EU-27 for fatal accidents at work.

(per 100 000 working people)

Source: Eurostat (hsw_mi01)

Older people moving into retirement

Most people in work will at some point start to think about their retirement. While early retirement might sound like a good idea, it is likely that an early exit from the labour force will have consequences for future income. Phased retirements promote a flexible transition into retirement, while retaining some of the financial and social benefits of working.

Table 1 provides information on statutory pension ages across EU Member States; the pensionable age was frequently found to be higher for men than women. In 2020, the lowest statutory pension age was 60 years in Austria and Poland (for women only), while the highest was 67 years in Greece (for both men and women). Table 1 also provides a subjective indication as to the age when people would ideally continue working and until what age they thought they could continue to do their current job; this information refers to a survey carried out during February-September 2015. Contrary to the general pattern observed for a majority of EU Member States, women in the Netherlands and Finland wanted to work until a later age than men.

(years)

Source: Extending working life: what do workers want?, Eurofound, 2017 and the Finnish Centre for Pensions (https://www.etk.fi/en/)

Almost one third of older people who continued to work while receiving a pension did so for non-financial reasons

While some people frequently dream of their last day at work before being able to retire, others who already receive a pension continue working; note, this could be a survivors’ pension (due to the death of a spouse). In 2012, more than one third (37.5 %) of people aged 50-69 years in the EU-28 who received a pension but continued working did so in order to have sufficient income; a further 14.6 % did so to have sufficient income and to establish/increase their future pension entitlements and 6.8 % did so uniquely to establish/increase their future pension entitlements (see Figure 17). As such, almost three tenths (29.2 %) of people in the EU-28 who received a pension and continued to work cited non-financial reasons for continuing to work (for example, job satisfaction).

More than a quarter of people aged 55-64 years who were no longer in employment left their last job to take normal retirement

Figure 18 details information on the main reasons why people who are no longer in employment left their last job [4]. In 2019, more than one quarter (31.6 %) of the EU-27 workforce aged 55-64 years who were not in employment left their last job to take normal retirement, while a further 15.9 % did so to take early retirement, 15.8 % for reasons of illness or disability and 14.2 % because they had been dismissed or made redundant; these were the four most common reasons for leaving a job among people aged 55-64 years. Among people aged 65-74 years not in employment, more than two thirds (69.4 %) cited normal retirement and 14.3 % early retirement as the principal reason for leaving their last job.

Source data for tables and graphs

Notes

- ↑ Employed persons include those who, during the reference week when the labour force survey was conducted, worked for one hour or more for pay, profit or family gain, or who had a job but were temporarily absent from work.

- ↑ The employment rate is defined as the number of persons employed, expressed as a percentage of the total population (for any given age group).

- ↑ The information presented is based on an aggregate covering NACE Section A and Sections C-N.

- ↑ As people may forget over time, this indicator is restricted to those people who had stopped work within the previous eight years.

Direct access to

Online publications

Categories of articles

Individual articles

- LFS main indicators (t_lfsi)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (t_lfsa)

- LFS series - specific topics (t_lfst)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Employment and activity - LFS adjusted series (lfsi_emp)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- LFS series - specific topics (lfst)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (lfso)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Health (hlth), see:

- Health and safety at work (hsw)

Metadata

- Employment and unemployment (Labour force survey) (ESMS metadata file — employ)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (ESMS metadata file — lfso)

- 2017 Self-employment (ESMS metadata file — lfso_17)

- Accidents at work (ESMS metadata file — hsw_acc_work)

Further methodological information