Ageing Europe - statistics on housing and living conditions

Data extracted in July 2020.

Planned article update: February 2024.

Highlights

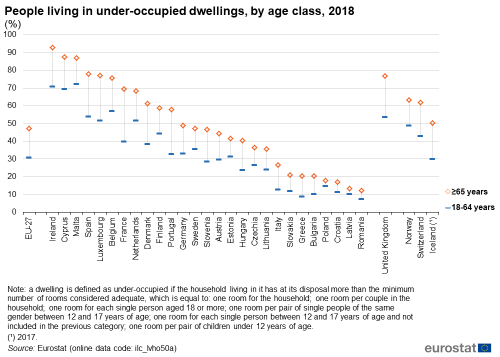

In 2018, the share of older people (aged 65 years or more) living in under-occupied dwellings in the EU-27 was close to half (47 %), compared with less than one third (31 %) for working-age adults (aged 18-64 years).

Older women (aged 75 years or more) in the EU-27 were more likely than older men to face severe difficulties paying for basic goods and services in 2019, with the severe material deprivation rate for older men at 3.3 % and at 6.0 % for older women.

Ageing Europe — looking at the lives of older people in the EU is a Eurostat publication providing a broad range of statistics that describe the everyday lives of the European Union’s (EU) older generations.

Full article

Household composition among older people

Recent decades have been characterised by a fall in the average size of households, reflecting — at least in part — lower fertility rates, a higher number of divorces and the dissolution of extended households. A growing number (and share) of older people in the EU are living alone (particularly older women): they form a particularly vulnerable group in society, with an increased risk of poverty or social exclusion.

Older women were more likely to be living alone …

Figure 1 shows there are considerable differences between the sexes in relation to the composition of private households [1]. In 2018, almost three fifths (58.0 %) of all men aged 65 years or more living in the EU-27 shared their household with a partner (but no other persons in the household); the corresponding share for women of the same age was much lower, at 39.0 %. In Cyprus and the Netherlands, approximately three quarters of all older men were living in households as part of a couple, while this share was less than half in Spain, Latvia, Malta, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Romania and Poland — where a relatively high proportion of older men were living in other types of household, for example, with other family members, friends or other persons.

Older women (aged 65 years or more) were much more likely to be living alone: in 2018, the share of older women living in households composed of a single person was 40.2 % across the EU-27, while the share for older men was 21.8 % [2]. More than half of all older women in Denmark and Estonia were living alone, while the lowest shares of older women living alone were recorded in Cyprus (23.4 %) and Spain (31.0 %).

(% share of older men/older women living in private households)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvps30)

… they were also more likely to be living in institutional households

The overwhelming majority of older people continue to live in private households (either alone, with their spouse or with other persons). Nevertheless, some older people move into institutional households, such as retirement or nursing homes; this may occur out of choice (for example, not wishing to live alone) or because it is no longer possible for older people to carry on living at home (for example, due to complex long-term care needs). The very old are more likely to be frail and therefore to need services such as those provided within institutional households.

While most healthcare costs in the EU are covered by social protection systems, long-term social care is usually treated in a different manner; indeed, it is rare that such services are covered to the same extent as healthcare. This means that the responsibility for financing institutional care often resides with the older person needing such care (or with their family). In 2011 (the latest census data that are available), 3.8 % of older women (aged 65 years or more) in the EU were living in an institutional household. This was twice as high as the corresponding share recorded for older men (1.9 %).

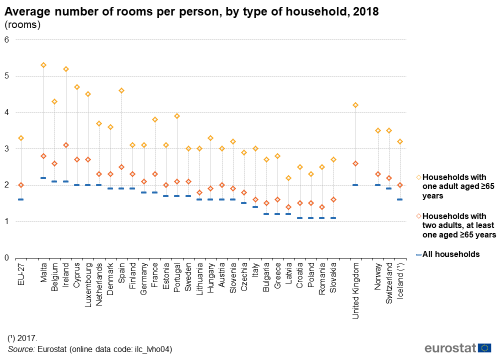

Older people living in under-occupied dwellings

Contrary to the issue of over-crowding, which tends to affect younger people and those living in some of Europe’s largest cities, older people are more likely to be living in under-occupied dwellings [3].

In 2018, households in the EU-27 had an average of 1.6 rooms [4] per person (see Figure 2). Older people had more rooms in their dwellings: on average, 2.0 rooms per person for households composed of two adults at least one of which was aged 65 years or more, and 3.3 rooms per person for households composed of a single person aged 65 years or more. The most common cause of under-occupation is because older individuals or couples continue to live in the same property long after their children have left the family home, despite it being, for example, large, expensive to heat and maintain, or ill-adapted.

The average number of rooms per person for households composed of a single person aged 65 years or more was particularly high in Belgium, Luxembourg, Spain and Cyprus (4.3-4.7 rooms in 2018), rising to 5.2 rooms in Ireland and peaking at 5.3 rooms in Malta; all six of these EU Member States also recorded a relatively high average number of rooms per person for all households. By contrast, the average number of rooms was relatively low for all households and for households composed of older people in Latvia and across most of the eastern EU Member States (except for Hungary).

(rooms)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho04)

Approximately half of all older people were living in under-occupied dwellings

In 2018, the share of working-age adults (aged 18-64 years) living in under-occupied dwellings across the EU-27 was less than one third (30.7 %). By contrast, the proportion of older people (aged 65 years or more) living in under-occupied dwellings was close to half (46.9 %). This pattern — a higher share of older people than working-age adults living in under-occupied dwellings — was observed in all of the EU Member States. The share of older people living in under-occupied dwellings peaked at 92.8 % in Ireland, and was more than 85 % in Cyprus and Malta.By contrast, in Poland, Croatia, Latvia and Romania less than 20 % of older people were living in under-occupied dwellings; the lowest share was recorded in Romania (12.0 %). This wide disparity between Member States may reflect, among others, whether older people were living predominantly: in houses or flats/apartments; in urban or rural areas; on their own or with their (extended) family.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho50a)

Housing affordability for older people

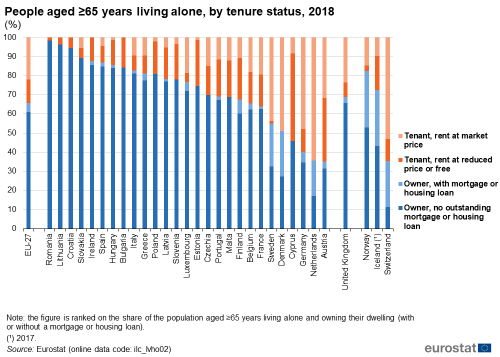

Older people (aged 65 years or more) are more likely than younger people to be homeowners. In 2018, some 60.9 % of older people living alone in the EU-27 were homeowners with no outstanding mortgage or housing loan (see Figure 4); just 4.7 % were homeowners who had not yet paid-off their mortgage. By contrast, more than one third (34.4 %) of older people living alone in the EU-27 were tenants: a higher share — 21.9 % of older people living alone — were tenants with a rent at market prices, while 12.5 % were tenants with a rent at reduced price or free (for example, those living in social housing).

The overall tenure structure of different housing markets is illustrated in Figure 4. In several eastern and southern EU Member States, as well as Lithuania and Ireland, a very high share of older people living alone were homeowners. At the other end of the range, more than half of the older people living alone in Cyprus, Germany, the Netherlands and Austria (which recorded the highest share, at 64.9 %) were tenants.

Older people living alone were more likely to be homeowners

Older people (aged 65 years or more) living alone in the EU-27 were more likely (than average) to be homeowners, irrespective of whether they had an outstanding mortgage or housing loan: in 2018, almost two thirds (65.6 %) of older people living alone owned their home, compared with 51.0 % of the total population that were living alone. This generational gap was particularly pronounced in Italy, Luxembourg, Finland, Greece and Spain, where older people were much more likely to be homeowners. By contrast, the share of older people living alone who were homeowners in Slovakia and Malta was slightly lower than the average recorded for all people living alone.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho02)

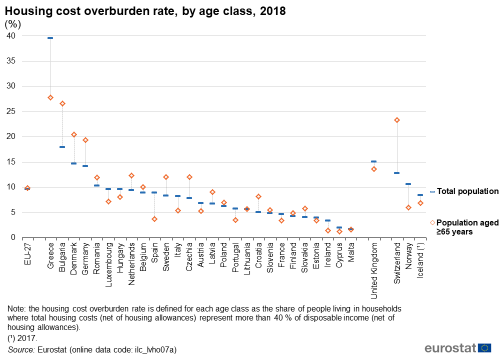

Around one tenth of older people face a burden from their housing costs

During the last few decades, an increasing share of the average household budget in the EU has been devoted to housing, while the share of expenditure on items such as food and clothing has fallen. Housing costs include expenses such as rent or the interest part of mortgage payments, as well as property-related local taxes, the cost of utilities (such as water, electricity or gas), other fuels (such as solid or liquid fuels and bottled gas), home repairs and maintenance. The housing cost overburden rate is defined as the share of people living in households where total housing costs (net of housing allowances) represent more than 40 % of disposable income (net of housing allowances).

In 2018, approximately one tenth (9.6 %) of the EU-27 population was overburdened by the cost of their housing. An almost identical rate was recorded for older people (aged 65 years or more), at 9.8 %. The share of older people whose housing costs accounted for more than 40 % of their disposable income was much higher — at least 20.0 % — in Denmark, Bulgaria and Greece, where the highest rate was recorded (27.8 %); this was also the case in Switzerland (23.3 %).

Although the proportion of older people who were overburdened by their housing costs in Greece was relatively high (at 27.8 %), it was considerably less than the rate experienced by the whole population (39.5 %). In a similar vein, older people in Spain, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal and Ireland were less likely to be overburdened by housing costs — a difference of at least 2.0 percentage points — than other generations. By contrast, the housing cost overburden rate was at least 2.0 percentage points higher for older people than it was for the whole population in Latvia, the Netherlands, Croatia, Sweden, Czechia, Germany, Denmark and Bulgaria (where a difference of 8.7 percentage points was observed); this gap was even greater in Switzerland (10.5 percentage points).

In 2018, the share of older women (aged 65 years or more) in the EU-27 that were overburdened by their housing costs stood at 11.3 %. This was 3.4 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for older men (7.9 points). This pattern — where a greater share of older women than older men were overburdened by housing costs — was repeated in all but three of the EU Member States. The housing cost overburden rate was higher among older men in Ireland and Malta; note that in both cases, relatively few older people (in general) were overburdened by housing costs. In Cyprus, equal shares of older men and older women were overburdened by housing costs, just 1.2 % — the lowest shares across the EU Member States for either sex.

By contrast, the housing cost overburden rate for older women in 2018 was more than 10.0 percentage points higher than the corresponding rate for older men in Bulgaria and Greece. Relatively high shares of older women (compared with older men) were also overburdened by their housing costs in Sweden, Czechia and Romania.

Older people living in material deprivation

Defining material deprivation

Material deprivation is the enforced inability to afford basic goods and services that are considered by most people to be desirable (or even necessary) to lead an adequate life. Severe material deprivation is defined as the enforced inability to pay for at least four of the following nine items: to pay rent, mortgage or utility bills or hire purchase repayments; to keep home adequately warm; to face unexpected expenses; to eat meat or proteins regularly; to go on holiday; to pay for a television set; to pay for a washing machine; to pay for a car; to pay for a telephone.

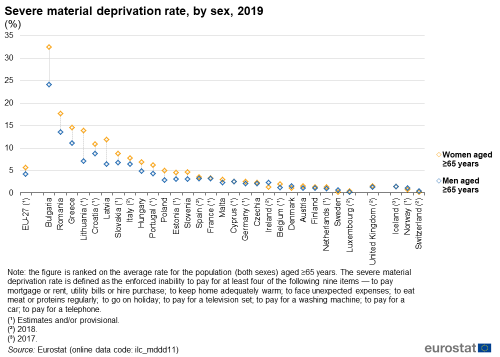

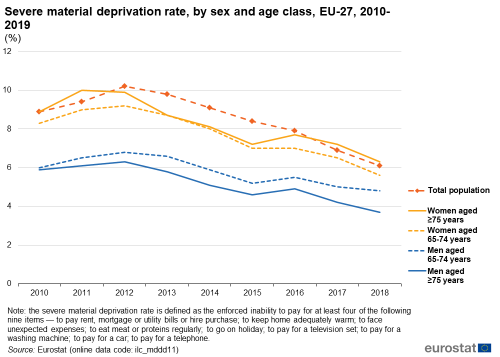

Older people were less likely to face severe material deprivation

Figure 7 shows the development of EU-27 severe material deprivation rates for older people during the period after the global financial and economic crisis. The impact of the crisis was apparent through until 2012, after which severe material deprivation rates for older people fell at a relatively fast pace, interrupted only by a slight upturn in 2016. Although not shown, severe material deprivation rates for younger generations were much higher than those for older people. Furthermore, having initially fallen post-2012, severe material deprivation rates for younger people, such as those in their twenties, were increasing again in 2019.

Older women are generally more likely (than older men) to face severe difficulties in being able to pay for basic goods and services: this gap between the sexes peaked in the aftermath of the crisis, but narrowed thereafter for people aged 65-74 years. A somewhat different pattern was observed for people aged 75 years or more: in 2019, the EU-27 severe material deprivation rate for men of this age was 3.3 %, while the corresponding rate for women was considerably higher, at 6.0 %. This may reflect a range of factors, including: labour market experiences (the gender pay gap; women often having lower pension entitlements); increased longevity among women (extending the period over which their financial resources need to last); a greater share of older women living alone (a two-person household needs relatively fewer resources per person than a single-person household to maintain the same standard of living).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddd11)

Figure 8 shows that in 2019 the EU-27 severe material deprivation rate for older people (aged 65 years or more) was 5.0 %; this was 0.7 percentage points less than the overall rate recorded for the whole population. Although this inter-generational divide was generally in favour of older people, there were eight EU Member States — in eastern parts of the EU or in the Baltic Member States — where the severe material deprivation rate was higher for older people than it was for the total population; the two rates were the same in Slovakia. This was most notably the case in Bulgaria, as the severe material deprivation rate for older people stood at 29.1 % compared with an average of 19.9 % for the whole population.

The severe material deprivation rate for older women (aged 65 years or more) was generally higher than the corresponding rate recorded for older men across the EU Member States. In 2019, the rate for older women in the EU-27 was 5.6 %, some 1.4 percentage points higher than the corresponding rate for older men (4.2 %). This pattern — where a greater share of older women than older men faced severe material deprivation — was repeated in all but four of the EU Member States. The severe material deprivation rate was higher among older men in Denmark, Sweden and Ireland (2018 data); the gap was widest in Ireland at 1.0 percentage points. In Cyprus, equal shares of older men and older women faced severe material deprivation.

In 2019, the severe material deprivation rate for older women was 8.4 percentage points higher than the corresponding rate for older men in Bulgaria; this was the widest gap between the sexes among the EU Member States. Relatively large differences — with rates for older women at least 4.0 percentage points higher than for older men — were also recorded in Lithuania, Latvia and Romania.

Older people were less likely to be in arrears

Economic safety is a term used to encompass people’s overall vulnerability (or resilience) to adverse financial situations and the existence (or otherwise) of support mechanisms to provide a safety net for individuals in need. One specific measure used within this domain is household arrears — in other words, the share of households that were late with payments for a mortgage or rent, utility bills or hire purchase (repayments that are generally made with a monthly frequency).

In 2019, the proportion of EU-27 households in arrears was 8.9 %. Older people were much less likely to be in arrears: 4.3 % of households with one adult aged 65 years or more were in arrears, while the share for households with two adults (at least one aged 65 years or more) was even lower, at 3.5 %. This inter-generational divide likely reflects, among other factors, the high number of older homeowners who have already paid-off their mortgage, as well as different attitudes to debt between the generations.

Households composed of older people were generally far less likely (than the average for all households) to be in arrears; Figure 10 shows that this pattern was repeated in all but one of the EU Member States, the exception being Romania for adults aged 65 years or more who were living alone. In absolute terms, the share of households with one adult aged 65 years or more in arrears was much lower than the corresponding average for all households in Greece and Cyprus, with a difference of 13.9 percentage points in both cases. In relative terms, the difference was greatest in Cyprus, Belgium, Spain (2018 data) and Luxembourg (2017 data), as the share of all households that were in arrears was 4.0-6.0 times as high as the share among households with one adult aged 65 years or more.

Older people living alone were more likely to be impacted by energy poverty

Large shares of the housing stock in some parts of Europe date back more than a century. These older properties are more likely to be in a poor condition, suffering from issues such as poor insulation and damp, or hazards such that it is more likely that their occupants may fall or otherwise injure themselves.

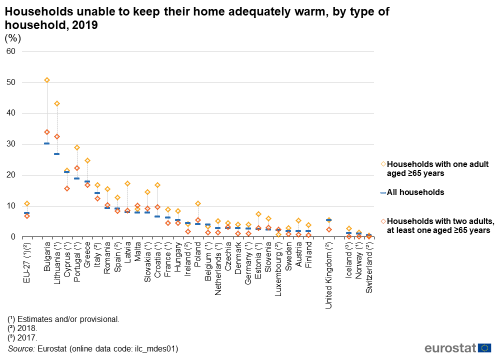

One measure of energy poverty is the inability to keep a home adequately warm: this indicator is often connected to low levels of household income, energy inefficient homes and (relatively) high energy costs. Figure 11 reveals that in 2019 some 7.6 % of EU-27 households were unable to keep their home adequately warm. Among households composed of a single adult aged 65 years or more, this share was more than one tenth (10.7 %), while it was lower (6.7 %) for households composed of two adults at least one of which was aged 65 years or more. A variety of situations were observed among the EU Member States:

- in Luxembourg the opposite pattern was observed, with a below average share of households composed of a single adult aged 65 years or more unable to keep their home adequately warm and an above average share for households composed of two adults at least one of which was aged 65 years or more;

- in Belgium and Ireland (2018 data), the share of households unable to keep their home adequately warm was systematically lower (than the average for all households) for both types of household composed of older people;

- by contrast, in most of the Baltic and eastern Member States (but not Hungary), as well as in Malta and Portugal, the share of households composed of older people unable to keep their home adequately warm was higher (than the average for all households) among both types of household composed of older people.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdes01)

Older people were less likely to live in a dwelling with a leak, damp or rot

In 2018, some 13.6 % of the EU-27 population lived in a dwelling with a leaking roof, damp walls, floors or foundation, or rot in window frames or floor (see Figure 12); the corresponding share among older people (aged 65 years or more) was somewhat lower, at 11.1 %. This pattern was repeated in a majority of the EU Member States, with a lower share of older people compared with the whole population living in dwellings with a leak, damp or rot. This difference was particularly pronounced in Denmark, where the share of the older people living in dwellings with a leak, damp or rot was less than half the average for the whole population; this was also the case in Switzerland and Norway.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdho01)

Living conditions for older people in their local area

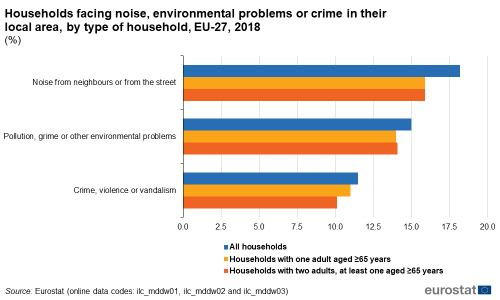

There are numerous issues that may impact on the quality of life experienced by older people in their local community. Among these are concerns linked to noise, pollution and crime, all three of which may be more prevalent in predominantly urban (rather than rural) regions. As such, the information presented in Figures 13 and 14 should be considered in unison with the population distribution of older people by urban-rural typology (see Chapter 1). Indeed, this may explain, at least in part, why in 2018 households composed of older people in the EU-27 were generally less likely (than all households) to report that they faced noise, environmental problems or crime in their local area.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddw01), (ilc_mddw02) and (ilc_mddw03)

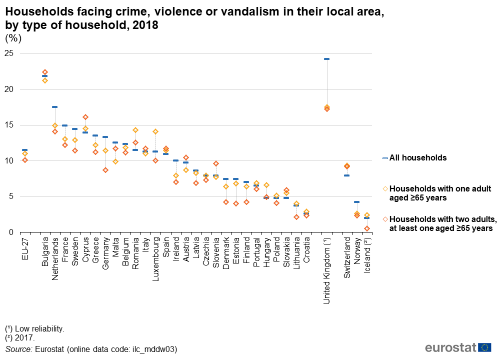

Figure 14 focuses on the share of households reporting that they faced crime, violence or vandalism in their local area. In 2018, some 11.5 % of all households across the EU-27 reported these issues, while the corresponding shares for households composed of older people were slightly lower (irrespective of whether the household was composed of a single person aged 65 years or more or two adults, at least one of whom was aged 65 years or more). Among the EU Member States where relatively high shares (more than 11.5 %) of households reported that they faced crime, violence or vandalism it was common to find a smaller proportion of older people reporting such issues; this was notably the case in Germany, the Netherlands, France and Sweden. By contrast, a relatively high proportion of households in Cyprus and Bulgaria reported that they faced crime, violence or vandalism in their local area and that this was more prevalent among households composed of older persons; in Cyprus this was the case for both types of households composed of older persons, whereas In Bulgaria it was only the case for households with two adults at least one of whom was aged 65 years or more.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddw03)

Source data for tables and graphs

Notes

- ↑ These figures exclude people living in institutional households (for example, retirement or nursing homes).

- ↑ It is important to note that the difference between these shares was further compounded, insofar as the total number of older women was much higher than the total number of older men (as shown in Chapter 1).

- ↑ An under-occupied dwelling is one that is deemed to be too large for the needs of the household living in it, in terms of excess rooms (and more specifically bedrooms); for more information refer to the note under Figure 3.

- ↑ A room is defined as a space of a housing unit of at least four square meters such as normal bedrooms, dining rooms, living rooms and habitable cellars, attics, kitchens and other separated spaces used or intended for dwelling purposes with height of more than two metres and accessible from inside the housing unit.

Direct access to

Online publications

Categories of articles

- Living conditions (t_ilc_lv)

- Housing conditions (t_ilc_lvho)

- Material deprivation (t_ilc_md)

- Material deprivation by dimension (t_ilc_mddd)

- Housing deprivation (t_ilc_mdho)

- Living conditions (t_ilc_lv)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

- Housing conditions (ilc_lvho)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- Economic strain (ilc_mdes)

- Economic strain linked to dwelling (ilc_mded)

- Housing deprivation (ilc_mdho)

- Environment of the dwelling (ilc_mddw)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

Metadata

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

Further methodological information