Ageing Europe - statistics on social life and opinions

Data extracted in July 2020.

Planned article update: February 2024.

Highlights

In 2017, 45 % of the EU-27 population aged 65-74 years spent at least 3 hours per week on physical activity outside of work, compared with 33 % for people aged 75 years or more.

In 2019, 60 % of the EU-27 population aged 16-74 years made at least one online purchase for private purposes, compared with 28 % for people aged 65-74 years.

In 2018, 64 % of the EU-27 population aged 15 years or more participated in tourism for personal purposes, compared with 49 % for people aged 65 years or more.

(% of people)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_ec_ibuy)

Ageing Europe — looking at the lives of older people in the EU is a Eurostat publication providing a broad range of statistics that describe the everyday lives of the European Union’s (EU) older generations.

This final article looks at some of the ways that older people spend their time: playing sports and remaining fit; participating in cultural activities, tourism and/or social media; returning to education; or socialising with family and friends. All of these activities provide a means for older people to remain active and connected to other members of society, through a network of supportive relationships, with policymakers and healthcare professionals generally agreeing this is beneficial for being happier and more content in older age.

Full article

Physical activity of older people

People at work often exert themselves either physically or mentally — which may help them to remain healthy. In a similar vein, many older people try to fight against the inevitability of ageing by remaining active and fit — keeping their bodies flexible and strong, or stimulating their intellect to keep their minds sharp.

Defining physical activity within the context of the EU survey on income and living conditions

Within the EU survey on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), the indicator on the total time spent on physical activity outside of work — as measured by an ad-hoc module in 2017 — concerns only those activities that:

- cause at least a small increase in breathing or heart rate (in other words, at least moderately demanding physical activities);

- are performed for at least 10 minutes continuously (in other words, without interruption).

As such, the information presented below is based exclusively on non-work-related physical activities, such as: sports and fitness, recreational leisure activities (for example, Nordic walking, brisk walking, cycling), or transport/commuting activities (for example, walking or cycling to work/school/college).

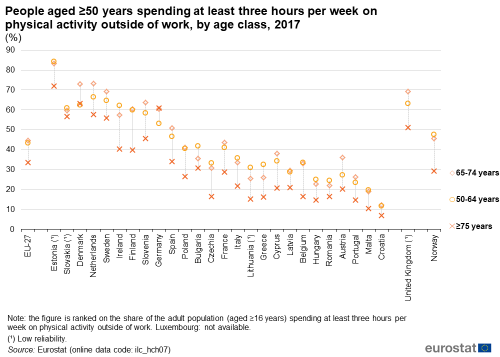

One third of people aged 75 years or more spent at least three hours per week on physical activity

In 2017, less than half (44.5 %) of the EU-27 adult population (aged 16 years or more) spent at least three hours per week on physical activity outside of work; the share for people aged 50-64 years was slightly lower, at 43.2 %. It is interesting to note that a somewhat higher proportion of people aged 65-74 years spent at least three hours per week on physical activity (44.5 %) — perhaps reflecting the additional free time that is available to pensioners — but then tailed off as people became older, falling to 33.4 % for those aged 75 years or more.

In 2017, the proportion of people aged 75 years or more spending at least three hours per week on physical activity (outside of work) peaked at 71.8 % in Estonia (see Figure 1). There were five other EU Member States where more than half of this age group spent at least three hours per week on physical activity: Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Slovakia and Sweden. In most of the Member States, the share of people aged 75 years or more spending at least three hours per week on physical activity was lower than the share recorded for people aged 65-74 years, reflecting increasing levels of illness, disease and frailty among older people. However, a different pattern was observed in Germany: as the share of people aged 75 years or more spending at least three hours per week on physical activity (60.8 %) was not only marginally higher than the share for people aged 65-74 years (60.4 %) but was also higher than the average for the whole of the adult population (54.4 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hch07)

Figure 2 provides an extra information of the population aged 65-74 years, comparing participation in physical activity outside of work for men and women. Across the EU-27 as a whole, men in this age range were more likely than women to have spent at least three hours per week on physical activity outside of work, 46.3 % compared with 42.8 %. However, a higher participation of men was not universally observed among the EU Member States: in Slovenia, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Estonia and Sweden, women aged 65-74 years were more likely than their male counterparts to have undertaken such physical activity and this was also the case in the United Kingdom.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hch07)

Older people participating in cultural activities

Culture can enhance quality of life: it provides an opportunity to engage with the world and may promote feelings of belonging, thereby contributing to well-being. The information presented below relates to a 2015 ad-hoc module that formed part of the EU survey on income and living conditions.

More than one third of people aged 75 years or more participated in cultural/sporting events

Participation in cultural and/or sporting events tends to decline as the population gets older. This may be linked to a range of issues, including: not having any interest; not having transport; having fewer social contacts with whom to participate together; poor health; lower levels of income; or living away from urban centres (where a majority of events take place).

In 2015, more than three fifths (61.6 %) of the EU-27 population aged 50-64 years participated in cultural and/or sporting events (at least once during the 12 months preceding the survey); lower shares were recorded for people aged 65-74 years (54.5 %) and for people aged 75 years or more (35.6 %). This pattern of falling participation rates for older people was repeated in each of the EU Member States, other than a marginal increase in the participation rate for people aged 65-74 years in the Netherlands (see Figure 3).

Among older people, the highest levels of participation in cultural and/or sporting events in 2015 were generally recorded in western and northern EU Member States; while this pattern also existed across the whole of the adult population (aged 16 years or more) it became more apparent for older age groups. For example, more than half of the population aged 75 years or more in Finland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, Denmark and Sweden participated in cultural and/or sporting events.

(% participating at least once in the previous 12 months)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp01)

A comparison for men and women aged 65-74 years is shown in Figure 4, comparing their participation in cultural and/or sporting events. Across the EU-27 as a whole, men in this age range were more likely than women to have participated in such events, 56.5 % compared with 52.7 %. However, a higher participation of men was not universally observed among the EU Member States: in Malta, the Netherlands, France, the Nordic Member States and the Baltic Member States, women aged 65-74 years were more likely than their male counterparts to have participated in cultural and/or sporting events and this was also the case in the United Kingdom, Norway and Iceland.

(% participating at least once in the previous 12 months)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp01)

In keeping with participation rates for cultural and/or sporting events, the share of people performing artistic activities generally fell as a function of age. The share of people performing artistic activities — both among the adult population at large or more specifically older people — was relatively low. In 2015, 4.2 % of the EU-27 population aged 65-74 years performed an artistic activity (at least once during the 12 months preceding the survey), while the share for people aged 75 years or more was lower, at 3.1 % (see Figure 5).

(% performing at least once in the previous 12 months)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp07)

When compared by sex (see Figure 6), the share of people within the population aged 65-74 years that performed artistic activities was higher for men (4.6 %) than for women (3.9 %). Among the EU Member States, there was no clear gender pattern in the proportion of people aged 65-74 years performing artistic activities. Cyprus recorded the same shares for men as for women, while in 12 Member States the shares were higher for men and in 13 the shares were higher for women (no data are available for Hungary). In absolute terms, the largest differences in the shares of men and women aged 65-74 years performing artistic activities were in Finland and Ireland: in the former, the share for men was 5.2 percentage points higher than the share for women; in the later, the share for women was 4.0 percentage points higher than for men.

(% performing at least once in the previous 12 months)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp07)

Education and digital society among older people

Learning is no longer confined to a single, specific phase of life covered by the years spent at school, college and/or university; rather, it has become a dynamic process covering all stages of life. Education has the potential to increase the productivity of older people, extend their careers, or improve their skills and knowledge. Lifelong learning enables people to lead more active and fulfilling lives, with a growing number of older people attending adult education courses or going (back) to university.

Approximately 1 in 16 people in the EU-27 aged 55-64 years participated in education and training

Education and training among older people may be linked to providing skills and motivation to remain within the labour force. Despite new opportunities opening up education to older people, it remains unsurprising that the proportion of people participating in education and training generally falls as a function of age. In 2019, some 12.4 % of the EU-27’s population aged 25-54 years took part in formal and non-formal education and training (during the four weeks preceding the labour force survey), a share that was 6.2 % among people aged 55-64 years and 2.9 % for people aged 65-74 years. In keeping with figures for the whole of the adult population (18-74 years), the Nordic Member States had the highest participation rates in education and training for older people (see Figure 7).

(% of population taking part in formal and non-formal education and training in the four weeks preceding the survey)

Source: Eurostat (trng_lfs_01)

The share of people aged 55-74 years that participated in education and training was substantially higher for women (5.6 %) than for men (3.9 %). Among the EU Member States, only four — Croatia, Belgium, Hungary and Luxembourg — recorded higher share for men than for women; the difference was less than 0.5 percentage points except in Luxembourg, where it reached 1.0 percentage points. In absolute terms, the largest differences in the shares of men and women aged 55-74 years participating in education and training were in the Nordic Member States: in Finland the share for women was 7.7 percentage points higher than for men, in Denmark the difference was 10.1 percentage points and in Sweden the difference was 13.5 percentage points.

(% of population taking part in formal and non-formal education and training in the four weeks preceding the survey)

Source: Eurostat (trng_lfs_01)

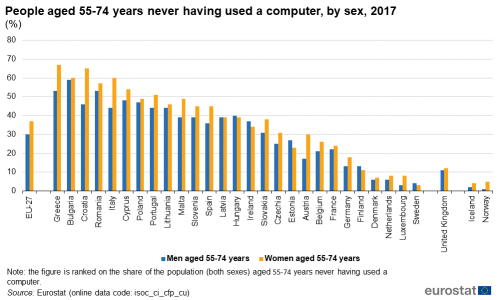

More than two fifths of people aged 65-74 years had never used a computer …

There is a digital divide between the generations: this term describes the gap between age groups in terms of their access to and use of modern information and communications technologies (ICTs); such technologies typically include mobile telephones, personal computers, laptops, tablets, the internet and related services.

The information presented in this section is taken from the annual EU survey on the use of ICT in households and by individuals. It reveals that older people are generally closing the digital divide; nevertheless, they remain relatively slow to adopt new technologies. Older men tend to be more likely than older women to make use of digital technologies; this may be linked to older men having been more exposed to new technologies in the workplace (either due to their choice of occupation or simply because a higher proportion of men than women work). These differences between the sexes may explain, at least in part, why the use of ICTs falls away for increasingly older age groups (a development that is magnified due to women accounting for a much larger share of survivors within this age category). By contrast, there is less evidence of a digital divide between the sexes among younger generations, for example, almost all young men and women make use of the internet on a daily basis.

While younger generations may find it difficult to imagine life without a smartphone or a personal computer / laptop, there were still one quarter (25 %) of people aged 55-64 years and more than two fifths (44 %) of people aged 65-74 years in the EU-27 in 2017 who had never used a computer. Across the EU Member States, the share of people aged 65-74 years having never used a computer was just higher than two thirds in Italy and Romania, and nearer to three quarters in Croatia (73 %), Bulgaria (74 %) and Greece (78 %). Figure 9 shows that a lower proportion of older people in 2017 had never used a computer than was the case for their counterparts in 2008: between 2008 and 2017, the share of the EU-27 population aged 55-64 years never having used a computer fell from 47 % to 25 % (with a reduction recorded for every Member State) while for the age group 65-74 years the share fell from 70 % to 44 %.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_ci_cfp_cu)

Across the EU-27 as a whole, the share of women aged 55-74 years in 2017 who had never used a computer was 37 %, whereas for men of the same age group the share was 30 % (see Figure 10). In most EU Member States, women aged 55-74 years were more likely than their male counterparts to have never used a computer, although the reverse was true in Estonia, Ireland, Finland, Sweden and Hungary, while there was no difference in the shares in Latvia.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_ci_cfp_cu)

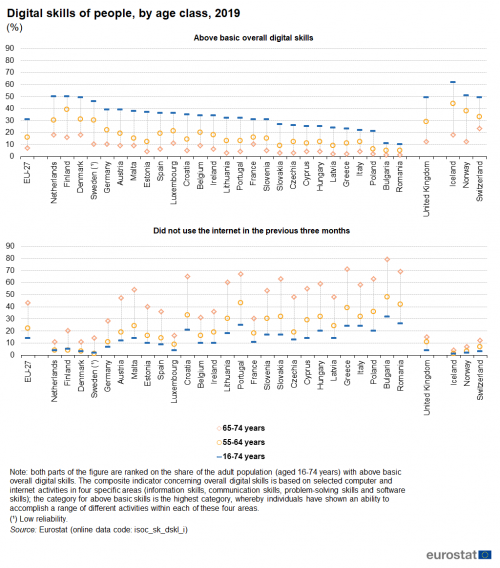

… and more than two fifths had not used the internet during the previous three months

In 2019, more than two fifths (43 %) of the EU-27 population aged 65-74 years did not use the internet during the three months preceding the Community survey on ICT usage (see Figure 11). Older people (aged 65-74 years) were therefore three times as likely as all adults (aged 16-74 years; 14 %) not to have used the internet. In percentage point terms, this gap between the generations was particularly marked in southern, eastern and Baltic EU Member States. For example, in Bulgaria and Greece the share of older people that had not used the internet was 47 percentage points higher than the share for the whole of the adult population; this difference was between 39 and 46 percentage points in Slovakia, Croatia, Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Portugal, Cyprus, Malta and Hungary.

Given that a higher proportion of older people have never used a computer nor recently used the internet, it is unsurprising that older people tend to possess fewer digital skills. In 2019, almost one third (31 %) of the EU-27 adult population had above basic digital skills: the shares for older people were much lower, at 16 % for people aged 55-64 years and 7 % for those aged 65-74 years. Older people are likely to make far greater use of ICTs in the future, given the continuing digitalisation of society and an increasing number of people with ICT skills passing into older age.

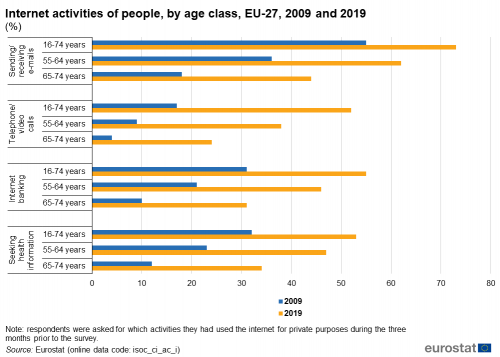

It is undeniable that the internet has the potential to be of considerable use to older people. For example, online shopping may free those with mobility issues from making difficult trips to the shops and in a similar vein, online banking can allow older people to manage their finances from home. The internet also provides numerous ways for older people to communicate with family and friends.

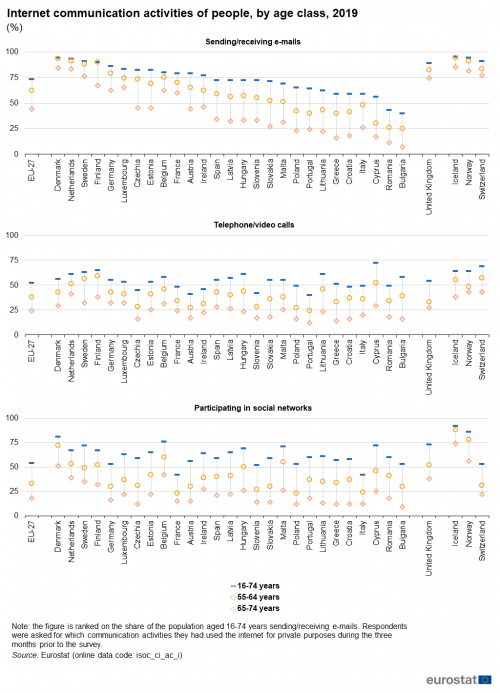

Figure 12 shows a range of internet activities, as carried out by people (for private purposes) during the three months preceding the survey. A lower than average share of older people (aged 65-74 years) in the EU-27 participated in each of the four activities shown. Sending/receiving e-mails was the most common activity among older people in the EU-27 (44 % in 2019), while they were less likely to use other forms of communication, such as telephone or video calls over the internet (24 %). Although the share of older people carrying out each of the four activities shown in Figure 12 was notably lower than the average for the adult population (aged 16-74 years) as a whole, the increases between 2009 and 2019 in the share of people carrying out each of these activities were similar in percentage point terms for both of these groups: for sending/receiving e-mails and seeking health information the increase was in fact greater among older people.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_ci_ac_i)

Less than one fifth of people aged 65-74 years made use of social networks

Older people (aged 65-74 years) in the EU-27 were less likely to use a range of internet communication activities than the population at large (defined here as adults aged 16-74 years). In 2019, less than one fifth (18 %) of older people participated in social networks, compared with an average of 54 % for all adults.

Figure 13 shows that the digital divide in communications is relatively narrow in several EU Member States that are characterised by high overall levels of digital activity, for example, Denmark and the Netherlands. By contrast, compared with national averages for the adult population as a whole, a relatively small proportion of people aged 65-74 years living in (most of) the southern, eastern or Baltic Member States used the internet for communication activities.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_ci_ac_i)

More than one quarter of people aged 65-74 years made online purchases

A growing share of older people are using the internet for online shopping; however, they remain less likely than other age groups to make purchases over the internet. In 2019, some 28 % of the EU-27 population aged 65-74 years made at least one online purchase (for private purposes) during the 12 months preceding the Community survey on ICT usage (see Figure 14); the corresponding share for people aged 55-64 years was 45 %, while the average for all adults (aged 16-74 years) was 60 %.

In 2019, a majority of older people (aged 65-74 years) in Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, made online purchases, with a peak of 65 % in Denmark. There were five EU Member States where less than 1 in 10 older people made online purchases, this ratio being lowest in Bulgaria and Romania at 2 % and 3 % respectively.

(% of people)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_ec_ibuy)

Tourism and older people

Recent years have seen an expansion in tourism among older people. This may, at least in part, be explained by: successive older generations becoming more accustomed to travelling; the relatively wealthy baby-boomer generation slowly moving into retirement; a growing share of older people living longer and healthier lives.

In contrast to the working-age population that may be constrained in terms of when they can take their holidays (for example, because of children’s school holidays or businesses closing down in the summer), older people who have already retired have far greater flexibility to choose when they go on holiday. Many take their holidays during shoulder and/or low seasons (thereby extending the tourist season in some destinations); this allows them to benefit from cheaper prices, while avoiding the crowds and high temperatures of peak periods.

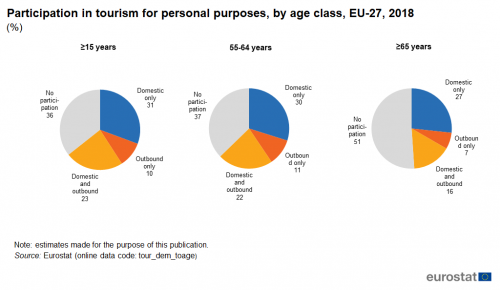

About half of all people aged 65 years or more participated in tourism

In 2018, some 64 % of the EU-27 population aged 15 years or more participated in tourism for personal purposes (therefore excluding tourism linked to business purposes). The corresponding share for people aged 55-64 years was slightly lower (at 63 %), while the proportion of older people (aged 65 years or more) participating in tourism was around half (49 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (tour_dem_toage)

This pattern — a lower share of older people participating in tourism — was repeated in each of the EU Member States for which data are available (see Figure 16 for coverage). Nevertheless, between three quarters and four fifths of all older people in Sweden, the Netherlands and Finland participated in tourism; a slightly lower share (74 %) was observed in Switzerland and an even higher share (87 %) in Norway. By contrast, this share was 12 % in Bulgaria and Romania.

Figures 15 and 16 show that domestic markets were the most popular holiday destination, both for the whole of the EU-27 adult population and for older people.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (tour_dem_toage)

In 2018, the EU-27 population aged 55 years or more accounted for 40.0 % of the total expenditure on tourist trips of at least one night. This share ranged across the EU Member States from highs of 44.0 % in Germany and 47.4 % in France down to less than 25.0 % in the Baltic Member States, Malta, Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania (where the lowest share was recorded, at 13.3 %).

Older people (aged 65 years or more) accounted for a higher share of total expenditure on tourist trips in 2018 than people aged 55-64 years in the Netherlands, Sweden, Luxembourg, Cyprus, Portugal, Germany, Greece and France (see Figure 17). Note that some of these EU Member States, such as Greece, Portugal and Germany, are characterised by relatively high proportions of older people within their total number of inhabitants, although the opposite is true in some others, such as Cyprus and Luxembourg.

(% share of total expenditure by all persons aged ≥15 years)

Source: Eurostat (tour_dem_exage)

Close to half of all people aged 65 years or more who did not participate in tourism cited health as a reason for not doing so

In 2016, almost half (47.2 %) of the EU-27 population aged 15 years or more said that financial reasons prevented them from participating in tourism. By contrast, a much lower share (33.5 %) of older people (aged 65 years or more) cited financial reasons as preventing them from participating. Older people were, unsurprisingly, also less likely (than the average for the whole adult population) to cite a lack of time as a reason for non-participation in tourism (see Figure 18).

Health issues were cited by close to half (45.7 %) of all older people in the EU-27 as a reason for not participating in tourism in 2016; this share was more than twice as high as the average recorded for the whole adult population (21.5 %). Older people were also more likely (than average) to say that safety was a reason for not participating in tourism, or to say that they simply had no interest in tourism.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (tour_dem_npage)

Contacts between older people, family and friends

Studies show that retired people who keep busy and maintain relationships and other social interactions are more likely to be happy and content with life. Changes in family structures mean that it is increasingly likely that older people will live alone and/or at a considerable distance from their family. As such, contacts with other people and the wider community become increasingly important for the well-being of older people.

Women are more likely than men to have regular daily contact with their family and relatives. In 2015, 29.2 % of older women (aged 65-74 years) in the EU-27 had daily contact; the corresponding share for older men was lower, at 20.7 % (see Figure 19). The share of older people in the EU-27 who had daily contact with their family and relatives was broadly similar to the average for the whole of the adult population (aged 16 years or more, both sexes combined).

While a relatively high share of older people aged 75 years or more had no contact with family and relatives …

By contrast, older people (aged 75 years or more) were more likely (than the average for the whole population) not to have had any contact [1] with family and relatives during a 12-month period prior to the EU survey on income and living conditions. In 2015, some 6.6 % of older men and 6.0 % of older women in the EU-27 reported having had no contact with family and relatives during the 12 months preceding the survey. The share of older women that had no contact with family and relatives was 2.7 times as high as the average for all adult women, while for older men it was 2.0 times as high.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp11)

… they were more likely to get together with family or relatives on daily basis

Figures 20 and 21 develop these findings by looking at the frequency of actually getting together with family and friends (rather than simply making contact). The information presented shows that older people (aged 75 years or more) were more likely to get together with family or relatives [2] every day than was typical for the adult population (aged 16 years or more) as a whole. In 2015, daily contacts were observed for more than one fifth (21.4 %) of older people in the EU-27, compared with an average of 16.8 % for the whole adult population.

In 2015, the highest shares of older people (aged 75 years or more) getting together with family or relatives on a daily basis were usually found in southern EU Member States. This was in keeping with general patterns observed for the total population (as a greater share of people in southern Europe tend to socialise), with Cyprus (60.5 %) and Greece (43.8 %) recording the highest proportions of older people aged 75 years or more getting together with family or relatives on a daily basis. By contrast, there were five Member States where the share of older people getting together on a daily basis with family or relatives was lower than the average recorded for the whole population: this pattern was observed in Slovakia, Germany, Bulgaria, Croatia and particularly Romania (18.8 % for older people aged 75 years or more compared with an average of 25.3 % for all adults).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp09)

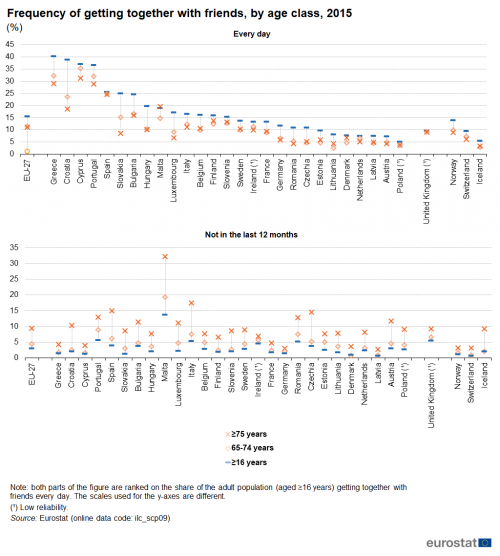

Older people in southern Europe were more likely to get together on a daily basis with friends …

In 2015, some 15.5 % of the EU-27 adult population (aged 16 years or more) got together with friends on a daily basis. As people age their circle of friends tends to diminish, while work and family commitments often make it more difficult to socialise; the share of the EU-27 population aged 50-64 years who got together with friends every day was 9.9 %. Retired people tend to have more free time than people at the end of their working careers and this may be one reason why a higher proportion of older people (than people aged 50-64 years) got together on a daily basis with friends — 11.3 % among those aged 65-74 years and 11.0 % among those aged 75 years or more (see Figure 21).

… but they were also more likely to be living in isolation

In 2015, almost one tenth (9.3 %) of older people aged 75 years or more in the EU-27 failed to get together with friends during the 12 months preceding the survey; this share was just over three times as high as the average for the whole of the adult population (2.9 %).

While the southern EU Member States recorded some of the highest shares of older people aged 75 years or more getting together with friends on a daily basis, they also recorded some of the highest shares of older people that did not get together with friends during the 12 months preceding the survey — for example, in Malta (32.2 %), Italy (17.4 %) or Spain (14.9 %). As such, while older people in these countries often had a higher level of contact and potential support from family, there was also a sizeable group of the elderly population having little social contact outside of their family circle.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp09)

Support networks and older people

Family and household structures in the EU are evolving, with increasing numbers of older people living alone. This has implications for the role of communities in ensuring that people remain connected and supported in older age.

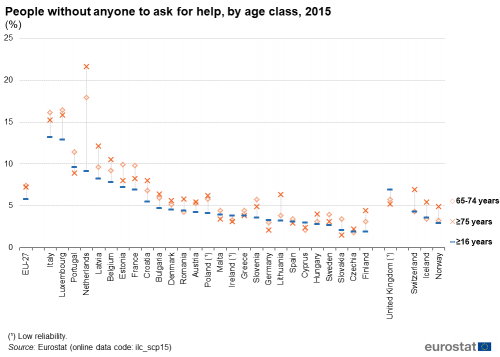

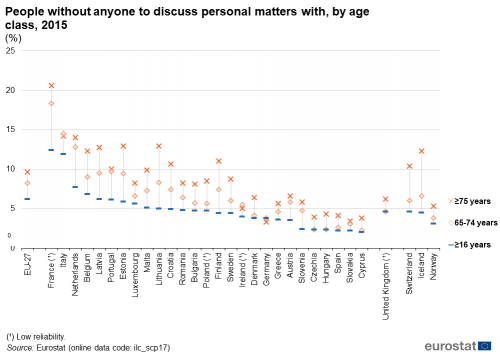

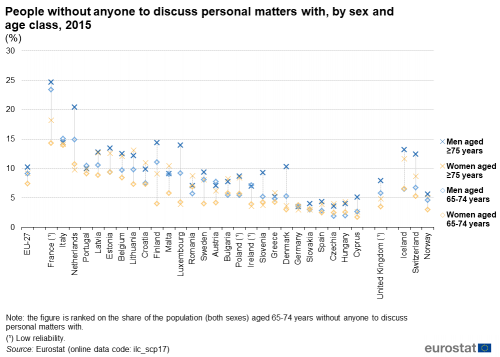

Almost one tenth of older people aged 75 years or more were without anyone with whom they could discuss personal matters

In 2015, the share of the EU-27 adult population (aged 16 years or more) without anyone to discuss personal matters with was 6.2 % (see Figure 22). This share grew as a function of age: 8.2 % of older people (aged 65-74 years) were without anyone to discuss personal matters as were 9.6 % of those aged 75 years or more.

A similar pattern was observed in the vast majority of the EU Member States: older people (aged 75 years or more) were generally the most likely to be without anyone to discuss personal matters with. In 2015, there were three exceptions — Germany, Ireland and Italy. The share of older people aged 75 years or more without anyone to discuss personal matters with was relatively high in the Netherlands (14.0 %), Italy (14.2 %) and particularly France (20.6 %) — although these figures reflected high overall shares for the whole adult population in these three Member States, rather than any age-specific difference.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp17)

Figure 23 provides similar information but with a distinction between men and women. In the EU-27 as a whole, older men (aged 65-74 years and 75 years or more) were more likely (than women in the same age groups) not to have anyone with whom they could discuss personal matters.

Higher shares for men in both age groups were observed in 14 EU Member States. In Estonia a higher share was observed for men than for women in the age group covering older people aged 75 years or more, while for older persons aged 65-74 years the shares were the same for both sexes; a similar situation was observed in Portugal, but with similar shares for the older age group and higher shares for men among older people aged 65-74 years. Elsewhere, the share of older women not having anyone with whom they could discuss personal matters was higher than the share for older men in at least one of the two age groups:

- in Germany, Poland and Slovakia, the share for women was higher among people aged 65-74 years;

- in Greece, Croatia, Lithuania and Malta, the share for women was higher among people aged 75 years or more;

- in Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary and Romania, the share for women was higher among both age groups covering older people.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp17)

In 2015, the share of the EU-27 adult population (aged 16 years or more) that was without anyone to ask for help was 5.8 % (see Figure 24). This measure of isolation rose modestly as the population became progressively older through to a peak of 7.4 % for people aged 65-74 years, while a slightly lower proportion (7.2 %) of older people aged 75 years or more were without anyone to ask for help. The highest shares of older people aged 75 years or more without anyone to ask for help were recorded in Italy (15.2 %), Luxembourg (15.8 %) and the Netherlands (21.6 %).

In 2015, the Netherlands was the only EU Member State where the proportion of older people aged 75 years or more without anyone to ask for help exceeded the average for all adults by at least 10 percentage points. In contrast, there were seven EU Member States where the share of older people aged 75 years or more without anyone to ask for help was lower than the average for the whole adult population: Spain, Malta, Cyprus, Slovakia, Portugal, Ireland and Germany.

A further presentation of the share of people without anyone to ask for help is presented in Figure 25, with shares for men and women aged 65 years or more. In the EU-27 as a whole, older men (aged 65-74 years and 75 years or more) were more likely (than women in the same age groups) not to have anyone to ask for help.

Higher shares for men in both age groups were observed in 22 EU Member States. In Estonia and Malta, the share of women without anyone to ask for help was higher than the share for men among people aged 65-74 years. In the Netherlands, Romania and Sweden, the share for women was higher (than the share for men) among both age groups covering older people.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp15)

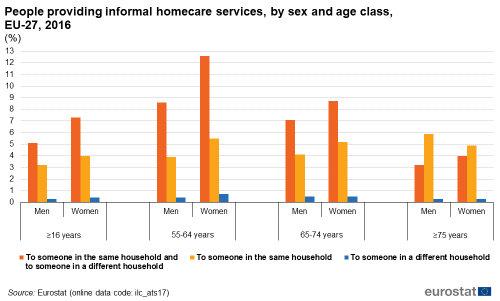

Women aged between 55 and 64 years were the most likely providers of informal homecare services

Intergenerational solidarity may be defined as social cohesion among different age groups linked by a mutually accepted understanding of concepts such as fairness and reciprocity. The provision of informal homecare [3] is a good example, insofar as care, transfers and social capital may flow both from older people to younger people or vice versa. Those individuals who decide to provide informal homecare services are likely to experience an impact on their working lives, as well as their financial security and more generally their well-being (unpaid carers may feel lonely or socially isolated as a result of their caring responsibilities).

Figure 26 confirms that women are generally more likely than men to provide informal homecare services. In 2016, the burden of providing these services was most often assumed by women aged 55-64 years, as more than one tenth (12.6 %) of women in this age group provided informal homecare services to both someone in the same household and to someone in a different household, 5.5 % provided such services to someone in the same household, and 0.7 % provided such services to someone in a different household.

It is interesting to note that the share of men who uniquely provided homecare services to someone in the same household rose (from the age group of 55-64 years) as a function of age, with a peak for older men aged 75 years or more, while the reverse was true for women as their share declined with age. In the oldest age group (covering persons aged 75 years or more), this share was higher for men (5.9 %) than for women (4.9 %), while in the two younger age groups the reverse was true.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_ats17)

Figure 27 focuses on the age group 65-74 years and presents the share of people providing homecare services to someone in the same household, comparing the shares for men and women. In the EU-27, this was 4.1 % for older men and 5.2 % for older women. In nearly all EU Member States, the share recorded for older men was lower than the share recorded for older women, the only exceptions — where the reverse was true— were Malta, Sweden, Lithuania, Hungary and Denmark; the shares were also higher for men than for women in the United Kingdom and in Norway. Among the Member States, the highest shares were recorded in Spain: 10.1 % of older men aged 65-74 years provided informal homecare services to someone in the same household as did 12.4 % of women in the same age group. The lowest shares of people aged 65-74 years providing homecare services to someone in the same household were recorded in Romania for men (0.8 %) and Sweden for women (1.1 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_ats17)

Across the EU Member States, informal care services are increasingly being recognised as part of the long-term care system, rather than something that takes place in the isolation of family homes. Some reform projects have piloted cash payments to informal carers, rewarding them for the cost-effective work they provide that enables older people to remain at home rather than being institutionalised.

In 2016, some 2.3 % of the EU-27 adult population (aged 16 years or more) provided at least 20 hours of informal homecare services per week (see Figure 28). This burden of providing informal homecare services was particularly apparent for older people (from the age of 55 years upwards); 3.6 % of people aged 55-64 years provided at least 20 hours of care per week, with this share slightly lower among people aged 65-74 years (3.5 %) and those aged 75 years or more (3.4 %). This pattern — a slightly higher share of people aged 55-64 years (than those aged 65-74 years or 75 years or more) providing at least 20 hours of informal homecare services — was repeated in approximately half (13) of the EU Member States. Spain recorded the highest shares of people providing at least 20 hours of informal homecare services (for each of the older age groups covered by Figure 21); the highest proportion was recorded for people aged 75 years or more (9.8 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_ats17) and (ilc_ats18)

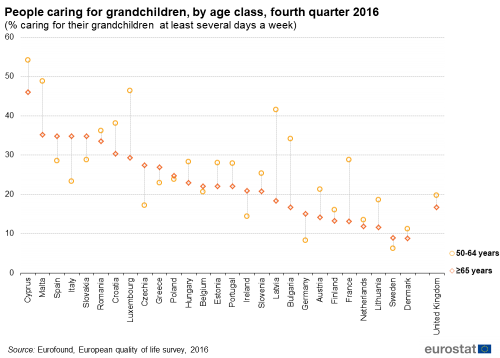

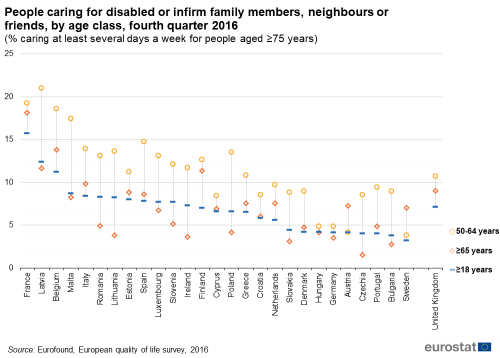

The greatest burden of providing care to grandchildren and elderly, disabled or infirm family members fell on people aged 50-64 years

The final part of this section provides two contrasting examples of intergenerational solidarity that cover the ends of the life cycle; the information presented is from a quality of life survey [4]. Figure 29 shows that in the fourth quarter of 2016, more than half (54.1 %) of all grandparents aged 50-64 years in Cyprus spent at least several days a week caring for their grandchildren, while Malta (48.8 %) and Luxembourg (46.4 %) also recorded relatively high shares. It was common to find that the share of people caring for their grandchildren was lower among older people (aged 65 years or more) than it was for people aged 50-64 years. However, there were several exceptions, for example, in Italy and Czechia. The different shares for these two age groups may in part reflect variations between EU Member States in the age distribution at which women give birth.

Figure 30 presents contrasting information, as it details the share of people who were caring for disabled or infirm family members neighbours or friends (aged 75 years or more). In the fourth quarter of 2016, some 15.7 % of the adult population (aged 18 years or more) in France was providing care at least several days a week to such a person; double-digit shares were also recorded in Latvia and Belgium. Generally, the highest proportion of care provided to such elderly people was provided by people aged 50-64 years; Sweden and Austria were the only exceptions, in both cases a higher proportion of older people (aged 65 years or more) were providing such care.

Opinions and life satisfaction of older people

This final section presents a snapshot of intergenerational differences in opinions, which may underline how divided some societies have become, not only in terms of objective measures (such as inequality or living standards) but also for a range of subjective measures. Indeed, it is increasingly the case that older and younger people sometimes appear to be living in almost different worlds (socially, economically, culturally and politically).

At the end of 2017, a public opinion survey [5] across the EU-27 found that lower shares of older people (compared with the whole of the adult population aged 15 years or more) considered themselves to be happy. Furthermore, a lower share of older people (than the adult population in general) thought that globalisation or immigration were good things (see Figure 31).

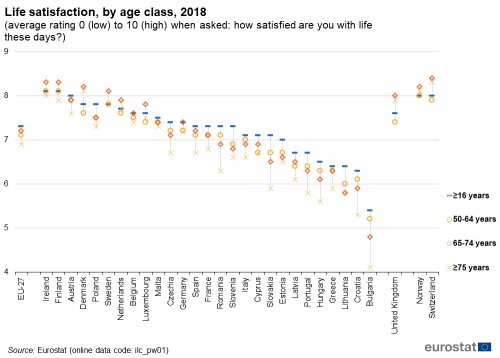

Older people are often more positive than middle-aged people in terms of life satisfaction

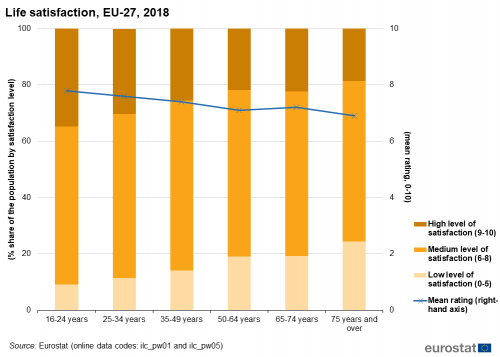

Figures 32-35 provide information on life satisfaction. Life satisfaction represents how a person evaluates or appraises his or her life taken as a whole. It is intended to cover a broad, reflective appraisal the person makes of his or her life. The term ‘life’ is intended here as all areas of a person’s existence. The variable therefore refers to the respondent’s opinion/feeling about the degree of satisfaction with his/her life. It focuses on how people are feeling ‘these days’ rather than specifying a longer or shorter time period. The intent is not to obtain the current emotional state of the respondent but to receive a reflective judgement on their level of satisfaction.

Life satisfaction tends to dip in middle age as people move towards retirement, at the end of their working careers. Note that this is also the period in many people’s lives when they have to provide care and ultimately deal with the death of their own parents. Thereafter, life satisfaction tends to stabilise/increase for older people (at least up until the point that they start to become frail or suffer from disability/chronic disease).

In 2018, the average rating for life satisfaction — on a scale of 0 (low) to 10 (high) — across the whole of the EU-27 adult population (aged 16 years or more) was 7.3. Average life satisfaction declined from a high of 7.8 among people aged 16-24 years to 7.1 among people aged 50-64 years. Thereafter there was a modest increase in life satisfaction for older people (aged 65-74 years; 7.2), followed by a further decline to 6.9 among people aged 75 years or more. Whereas more than one third (34.8 %) of 16-24 year olds reported a high level of satisfaction, this was the case for just over one fifth of people aged 50-64 years (21.9 %) or 65-74 years (22.3 %) and less than one fifth (18.7 %) among those aged 75 years or more.

Among the EU Member States, the highest levels of life satisfaction among older people were recorded in Ireland, the Nordic Member States, Austria and the Netherlands — see Figure 33. Ireland and Finland reported the highest average ratings of life satisfaction among people aged 50-64 years (both 8.1) and among those aged 65-74 years (both 8.3), while Ireland also had the second highest average rating of life satisfaction among people aged 75 years or more (8.0), just behind Denmark (8.1). For all three age groups, the lowest average ratings for life satisfaction were observed in Bulgaria.

(average rating 0 (low) to 10 (high) when asked: how satisfied are you with life these days?)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01)

Figure 34 provides a focus on the levels of life satisfaction experienced by older people aged 65-74 years for 2018. A higher proportion of people in this age group in the EU-27 declared themselves to be highly satisfied with their lives (22.3 %) than the proportion who had a low level of life satisfaction (19.2 %), with the remaining three fifths (58.5 %) reporting a medium level of life satisfaction. Based on these three levels of satisfaction, several groups of Member States can be identified.

In Bulgaria, Lithuania and Croatia, a larger proportion of people aged 65-74 years had a low level of life satisfaction than had either a medium or high level of satisfaction, with an absolute majority (65.8 %) in Bulgaria having a low level of life satisfaction.

At the other extreme were Ireland and Denmark, where a larger proportion of people aged 65-74 years had a high level of life satisfaction than had either a low or medium level of satisfaction, with an absolute majority (53.1 %) in Denmark having a high level of life satisfaction. A relative majority also had a high level of life satisfaction in Norway and an absolute majority in Switzerland (50.5 %).

Between these two groups were 22 Member States, all of which had at least a relative majority (and often an absolute majority) of people aged 65-74 years with a medium level of life satisfaction.

- In 12 of these, a higher proportion of people had a low level of life satisfaction than a high level, most notably in Hungary, Greece and Portugal.

- In the remaining 10 Member States, a higher proportion of people had a high level of life satisfaction than a low level, most notably in Finland, Sweden, Austria, the Netherlands and Luxembourg; this was also the case in the United Kingdom.

(% share of the population aged 65-74 years by satisfaction level)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw05)

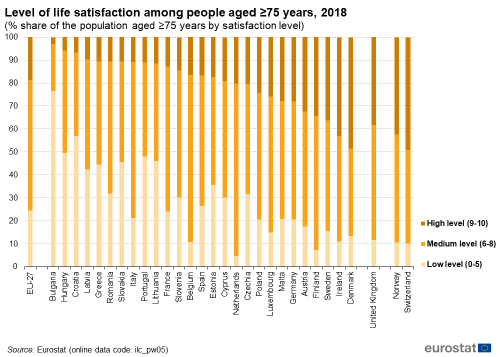

Figure 35 presents similar information but for older people aged 75 years or more, once again for 2018. For this age group, a smaller proportion of people in the EU-27 declared themselves to be highly satisfied with their lives (18.7 %) than the proportion who had a low level of life satisfaction (24.4 %), with the remaining share (56.9 %) reporting a medium level of satisfaction. Again, several groups of Member States can be identified.

In Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Portugal and Lithuania, a larger proportion of people aged 75 years or more had a low level of life satisfaction than had either a medium or high level of satisfaction, with an absolute majority in Bulgaria (76.6 %) and Croatia (57.0 %) having a low level of life satisfaction.

At the other extreme was Denmark, where a larger proportion of people aged 75 years or more had a high level of life satisfaction (48.5 %) than had either a low or medium level of satisfaction. A relative majority also had a high level of life satisfaction in Switzerland (49.1 %).

Between these two groups were 20 Member States, all of which had at least a relative majority (and often an absolute majority) of people aged 75 years or more with a medium level of life satisfaction.

- In 10 of these, a higher proportion of people had a low level of life satisfaction than a high level, most notably in Greece, Latvia and Romania.

- In the remaining 10 Member States, a higher proportion of people had a high level of life satisfaction than a low level, most notably in Ireland, Finland and Sweden; this was also the case in the United Kingdom and Norway.

(% share of the population aged ≥75 years by satisfaction level)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw05)

Source data for tables and graphs

Notes

- ↑ Contact can be made by telephone, SMS, letter, fax, or the internet (e-mail, social media and/or other internet communication tools); it should however be real contact/interaction, for example, a letter or a conversation, rather than simply sharing files (such as photographs).

- ↑ Family or relatives should be understood in its widest meaning: father, mother, children, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, nephews, nieces, and families-in-law.

- ↑ Homecare aims to make it possible for people to remain at home rather than use residential, long-term, or institutional based nursing care. Homecare may include healthcare (medical treatment, wound care, pain management and therapy), or help with daily tasks such as meal preparation, medication reminders, laundry, light housekeeping, shopping, transportation, and companionship.

- ↑ The European quality of life survey (EQLS) was conducted by Eurofound from September 2016 to March 2017. It measured subjective well-being, optimism, health, standards of living and aspects of deprivation, as well as work/life balance.

- ↑ Special Eurobarometer 471 on fairness, inequality and intergenerational mobility was coordinated by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Communication; fieldwork was carried out in December 2017.

Direct access to

Online publications

Categories of articles

- All articles on digital economy and society — households

- All articles on poverty and social exclusion

- All articles on quality of life

- All articles on residents' trips and destinations

Individual articles

- Living conditions (t_ilc_lv)

- ICT usage in households and by indivduals (t_isco_i)

- Digital skills (t_isoc_sk)

- Tourism (t_tour), see:

- Annual data on trips of EU residents (t_tour_dem)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

- EU-SILC ad-hoc modules (ilc_ahm)

- ICT usage in households and by indivduals (isco_i)

- Digital skills (isoc_sk)

- Tourism (tour), see:

- Annual data on trips of EU residents (tour_dem)

Metadata

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

- ICT usage in households and by individuals (ESMS metadata file — isoc_i)

- Annual data on trips of EU residents (ESMS metadata file — tour_dem)

Further methodological information