Ageing Europe - statistics on health and disability

Data extracted in July 2020.

Planned article update: February 2024.

Highlights

In 2018, women aged 65 years living in the EU-27 could expect to live for an additional 21.6 years and men of the same age an additional 18.1 years.

Across the EU-27 in 2018, women aged 65 years could expect to live an additional 10.0 years of their remaining lives in a healthy condition, while the corresponding figure for men aged 65 years was 9.8 years.

In 2018, people aged 65 years or more in the EU-27 were more likely than the whole of the population aged 16 years or more to have eaten fresh fruit and vegetables on a daily basis.

Ageing Europe — looking at the lives of older people in the EU is a Eurostat publication providing a broad range of statistics that describe the everyday lives of the European Union’s (EU) older generations.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. While Europeans are generally living longer lives, many face multiple health conditions or mobility problems in their later years. Relatively high rates of chronic illness, mental health conditions, disability and frailty may be reduced if structural, economic and social drivers of poor health are tackled at an early stage — for example, healthcare services investing more in education and screening services, or individuals making changes to their lifestyles.

Full article

Life expectancy and healthy life years among older people

Women aged 65 years could expect to live an additional 21.6 years

Life expectancy at birth has been increasing for a considerable period in the EU: official statistics reveal that life expectancy has risen, on average, by more than two years per decade for both sexes since the 1960s (although the latest figures available suggest that life expectancy stagnated or even declined during the last few years for several EU Member States). The gender gap for life expectancy at birth — higher life expectancy for women than men — slowly diminished during the period under consideration, as male life expectancy increased at a faster pace.

Figure 1 presents information on life expectancy at age 65 years; it shows the average number of years that a person of that age can be expected to live (assuming that current age-specific mortality levels remain constant). In 2018, a woman aged 65 years living in the EU-27 could expect to live an additional 21.6 years, while the corresponding figure for a man aged 65 years was lower, at 18.1 years. Among the EU Member States, the highest life expectancy at age 65 was recorded in France — 23.8 years for women and 19.7 years for men. Women aged 65 years could expect to live longer than men of the same age in each of the EU Member States. Some of the biggest gender gaps in life expectancy at age 65 were recorded among Member States with relatively low overall (both sexes) levels of life expectancy, for example the Baltic Member States and Poland, although the fifth biggest gap was observed for France.

(years)

Source: Eurostat (demo_mlifetable)

An international comparison of life expectancy at age 65 is provided in Figure 2 — note that it is based on data covering the period 2010-2015. Across the world, male life expectancy at age 65 years was 15.1 years, while female life expectancy was 2.7 years higher, at 17.8 years. The life expectancy of people aged 65 years in the EU-27 was relatively high compared with most of the other G20 countries, although overall life expectancy (an average for both sexes) was higher in Japan, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and South Korea.

(years)

Source: Eurostat (demo_mlexpec) and United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects 2019

At the age of 65 years, women can expect to live a smaller share of their remaining lives in a healthy condition

Whether the growing numbers of older people in the EU are living their later years in good health is a crucial consideration for policymakers. Additional years of life spent in an unhealthy condition (limitations in functioning or disability) are likely to result in extra demand for supplementary healthcare or long-term care services.

Figure 3 provides information on healthy life years (sometimes referred to as disability-free life expectancy), in other words, the number of years that a person can expect to live in a healthy condition without severe or moderate health problems. Unlike the measure for conventional life expectancy, this indicator may be used to summarise both the duration and quality of life. Across the EU-27 in 2018, women aged 65 years could expect to live, on average, for 10.0 years of their remaining lives in a healthy condition, while the comparable figure for older men was lower, at 9.8 years. As a share of their whole remaining life expectancy, this equated to 46.3 % for women and 54.1 % for men.

In general, those older people who were living in EU Member States with higher life expectancy tended to spend a lower proportion of their elderly lives with health problems. For example, compare the situation for older people in Sweden (with relatively high life expectancy) — who, on average, spent the vast majority of their later years in relatively good health — with that in Slovakia (with relatively low life expectancy), where older people spent approximately one quarter of their remaining lifespan in relatively good health.

(years)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_hlye)

Self-perceived health among older people

While most older people do not expect to be in perfect health throughout their later years, many hope that their health / physical condition will be such that they can continue to work for as long as they would like, go out and socialise, remain independent, and be able to look after themselves.

Data limitations for analysing self-perceived health

Health status and health services consumption may strongly differ between individuals living in institutions and in private households. It is important to note that the information presented below for self-perceived health conditions is taken from a survey where people living in collective households and institutions are generally excluded from the target population, which may lead to lower incidence of some health issues than might be observed with a complete coverage (considering that many of these conditions are more frequently experienced by older people who are unable to continue living at home).

The share of the population perceiving their own health as good or very good fell by age

Self-assessed health status provides information concerning how an individual perceives his/her health — rating it as very good, good, fair, bad and very bad. Figure 4 presents information for this indicator by age: as might be expected, the share of people perceiving their own health as good or very good declined with the age of the respondent. In 2018, some 68.5 % of the EU-27 adult population (aged 16 years or more) considered their own health to be good or very good. Just less than half (47.8 %) of older people (aged 65-74 years) in the EU-27 perceived their health to be good or very good, a share that fell to less than one third (32.3 %) among those aged 75-84 years and to around one fifth (20.6 %) for very old people (aged 85 years or more).

The pace at which the older population perceived their own health to be deteriorating varied considerably across the EU Member States. Nevertheless, the pattern of declining health as a function of age was repeated in all of the EU Member States in 2018. In Belgium, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Latvia and Portugal there was a relatively small difference — less than 3.0 percentage points — between the share of people aged 75-84 years perceiving their own health as good or very good and the equivalent share for very old people.

In 2018, the share of older people (aged 65-74 years) perceiving their own health as good or very good was less than half the corresponding share recorded for the whole adult population in Romania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Slovakia, Croatia, Hungary, Poland and Portugal. Even greater differences were registered in Latvia and Lithuania, as the share for people aged 65-74 years was around one third of the average for all adults in Latvia and approximately one quarter of the average for all adults in Lithuania.

(% of people perceiving their own health as good or very good)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_01)

A higher proportion of older men than older women tended to perceive their own health as good or very good

In 2018, the share of older men (aged 65 years or more) in the EU-27 perceiving their own health as good or very good was 43.1 %. This figure was 6.6 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for older women (36.5 %). Across the EU Member States, Ireland recorded the highest shares of older women (69.6 %) and older men (66.7 %) perceiving their own health as good or very good. Ireland was also the only Member State to record a higher proportion of older women than older men perceiving their own health as good or very good. By contrast, the share of older men perceiving their own health as good or very good was more than 10.0 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for older women in Spain, Malta, Cyprus and Romania (where the largest difference was recorded, at 11.7 percentage points).

(% of people perceiving their own health as good or very good)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_01)

Older people with high incomes were more likely to perceive their own health as good or very good

Figure 6 shows that, within the EU-27, self-perceived health was closely related to income, insofar as the proportion of older people (aged 65 years or more) who perceived their own health as good or very good rose as a function of income. In 2018, less than one third (30.1 %) of older people in the first income quintile (in other words, the 20 % of the population with the lowest incomes) perceived their own health to be good or very good. This share rose to more than half (52.6 %) for older people in the fifth income quintile (the 20 % of the population with the highest incomes).

In 2018, more than two thirds (68.3 %) of the population aged 65 years or more in Ireland considered their own health to be good or very good; this was also the case for a majority of older people in Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark and Belgium. By contrast, less than one fifth of older people in Poland, Estonia, Portugal and Latvia perceived their own health as good or very good, a share that was less than one tenth in Lithuania.

The close link observed for the EU-27 as a whole between income and self-perceived health was repeated in the vast majority of EU Member States. In 2018, the highest proportion of people aged 65 years or more perceiving their own health to be good or very good was consistently registered by the fifth income quintile. At the other end of the range, the lowest proportion of older people perceiving their own health to be good or very good was generally registered by those in the first income quintile, although this was not the case in Denmark, Ireland, Austria, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Slovakia (where the second income quintile registered the lowest share).

(% of people perceiving their own health as good or very good)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_10)

Healthy lifestyles among older people

Viewed in a broad context, health is more than just the absence of disease. Individuals can take responsibility for their own health by making a number of lifestyle choices — through action on smoking, diet, exercise or alcohol consumption — to impact on the risk of disease.

The tendency for older people to eat fresh fruit and vegetables was higher than average

Fresh fruit and vegetables intake is often cited as a factor behind increased longevity and protection against a range of illnesses/diseases (for example, cancer or osteoporosis). Older people (aged 65 years or more) in the EU-27 were more likely to have eaten fresh fruit and vegetables on a daily basis in 2017 than the whole of the adult population (defined here as people aged 16 years or more) — see Figures 7-10. Almost three quarters (72.4 %) of older people in the EU-27 ate fresh fruit on a daily basis, while the corresponding figure for fresh vegetables was slightly higher than two thirds (67.1 %).

In 2017, the share of older people eating fresh fruit on a daily basis ranged among the EU Member States from a high of 88.4 % in Italy down to a low of 31.0 % in Bulgaria. In Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Croatia, Hungary and Slovakia, less than half of all older people ate fresh fruit every day.

In 2017, older people were more likely than the adult population to consume fresh fruit on a daily basis in 17 of the EU Member States (in Czechia the shares were identical); the gap between the older generation and the population as a whole — in favour of older people — was particularly pronounced in the Netherlands, France, Sweden, Finland and Germany.

A higher proportion of older women (74.3 %) than older men (70.0 %) in the EU-27 ate fresh fruit on a daily basis in 2017. This pattern was particularly pronounced in Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, Estonia, Finland, Czechia and Slovakia, where the share among older women was more than 10.0 percentage points higher than the share among older men; the largest gap between the sexes was recorded in Denmark, at 17.9 percentage points. By contrast, in Portugal, Lithuania and Cyprus, it was more common for older men (rather than older women) to eat fresh fruit on a daily basis.

In 2017, the highest share of older people eating fresh vegetables on a daily basis was reported in Belgium (87.7 %), while more than four fifths of older people in Ireland, Luxembourg, Italy, France and Portugal also ate vegetables on a daily basis. By contrast, in Hungary, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Romania, Latvia, Czechia and Slovakia less than half of all older people ate fresh vegetables every day; the lowest share was recorded in Hungary (34.1 %).

There was generally a lower degree of variation between the generations concerning the share of people eating vegetables on a daily basis. Indeed, the EU Member States were split almost equally with 14 Member States reporting a higher share of older people (than the whole adult population) consuming vegetables on a daily basis in 2017. Relative to the whole adult population, a high share of older people in France, Luxembourg and the Netherlands consumed vegetables every day. By contrast, in Lithuania and Bulgaria a relatively small share of older people (compared with the whole adult population) ate vegetables daily.

A higher proportion of older women (68.8 %) than older men (64.8 %) in the EU-27 ate vegetables daily in 2017. This pattern was particularly pronounced in Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Germany, where the share among older women was more than 10.0 percentage points higher than the share among older men; the largest gap between the sexes was recorded in Sweden, at 13.9 percentage points. By contrast, there were six EU Member States where a higher proportion of older men (than older women) ate vegetables daily: Romania, Latvia, Bulgaria, Greece, Lithuania and Cyprus (where the largest gap in favour of older men was recorded; 3.2 percentage points).

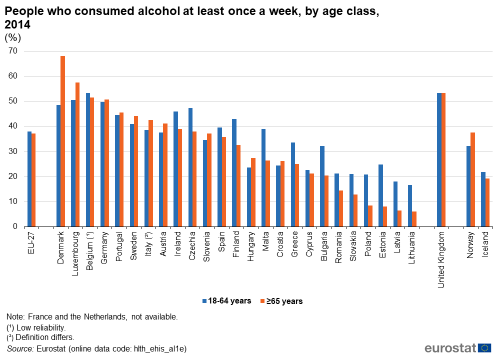

Relatively high and persistent levels of alcohol consumption may cause chronic physical or mental illness: alcohol intake is generally higher among men (than women). Figure 11 shows information on the consumption of alcohol by older people (aged 65 years or more). In 2014, some 37.2 % of older people in the EU-27 consumed alcohol at least once a week (16.8 % on a daily basis). This was very similar to the overall share among the working-age population, as 37.9 % of those aged 18-64 years consumed alcohol at least once a week (7.8 % on a daily basis, which was less than half the share recorded among older people). In 2014, the highest shares of older people consuming alcohol on a daily basis were recorded in Portugal (35.8 %), Italy (27.5 %), Denmark (27.4 %) and Spain (25.9 %), while more than half of all older people in Denmark, Luxembourg, Belgium and Germany consumed alcohol at least once a week.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_al1e)

In 2014, older men (aged 65 years or more) in the EU-27 were more than twice as likely as older women to consume alcohol: more than half (54.3 %) of all older men consumed alcohol at least once a week, compared with a share of close to one quarter among older women (24.1 %). In Estonia and Lithuania, the share of older men that consumed alcohol at least once a week was approximately 10 times as high as the share recorded among older women; this could be largely attributed to the very low share (no more than 2.0 %) of older women that consumed alcohol at least once a week.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_al1e)

Older people were less likely to be daily smokers

Smoking rates in the EU have declined in recent years, which may in part be due to legislation that introduced smoke-free areas in public places. Nevertheless, smoking remains the largest avoidable health risk in the EU and its consequences are a major burden on health care systems.

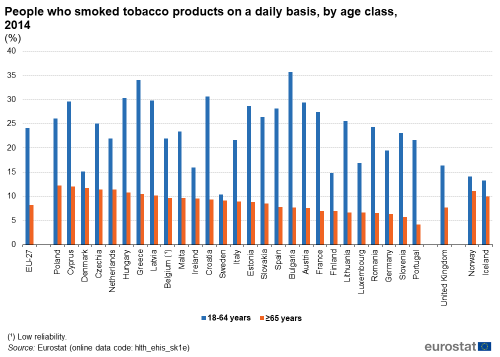

While it was relatively common for a higher share of older people (than the working-age population) to consume alcohol at least once a week — for example, in Denmark, Luxembourg, Italy or Hungary, as well as Norway — older people were systematically less likely (than the working-age population) to be daily smokers. Figure 13 shows that 8.2 % of older people in the EU-27 smoked on a daily basis, while the share for the working-age population was almost three times as high, at 24.1 %. Among older people, the proportion of daily smokers ranged from 4.1 % in Portugal to 12.2 % in Poland.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_sk1e)

In 2014, the share of older men (aged 65 years or more) in the EU-27 who smoked tobacco products on a daily basis was 11.2 %. This was approximately twice as high as the share recorded among older women (5.9 % of whom were daily smokers). In Lithuania, the share of older men who smoked tobacco products on a daily basis was almost 16 times as high as the share among older women. Relatively large disparities between the sexes were also recorded for older people living in Romania (where the share was about eight times as high for older men) and Cyprus (where the share was almost five times as high for older men).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_sk1e)

Older people were more likely than average to be obese

Obesity is another serious public health problem as it significantly increases the risk of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, type-2 diabetes, coronary heart disease and certain cancers. The body mass index (BMI) of an individual may be calculated as their body mass (in kilograms) divided by the square of their height (in metres); BMI = weight (kg)/height (m²). People with a body mass index of 30 or more are considered obese.

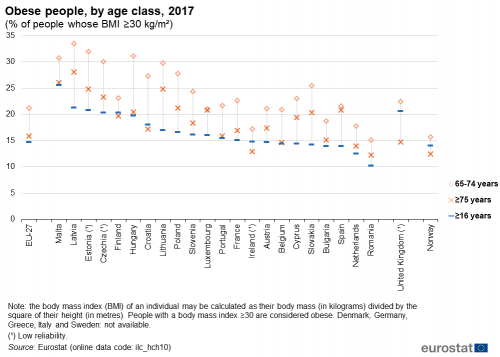

The likelihood that somebody is obese increases with age: more than one fifth (21.2 %) of people aged 65-74 years in the EU-27 were obese in 2017, while the average for the adult population (aged 16 years or more) was 14.7 %. At least 30.0 % of people aged 65-74 years in Czechia, Malta, Hungary, Estonia and Latvia were obese.

The situation was somewhat different for people aged 75 years or more: across the EU-27, some 15.8 % of this age group were obese. Indeed, the share of obese people often fell at quite a rapid pace as people became very old. For example, in Hungary and Croatia, the obesity rate was at least 50 % higher among people aged 65-74 years than it was for people aged 75 years or more. By contrast, there was almost no difference in obesity rates between these two groups of older people in Spain or Luxembourg.

(% of people whose BMI ≥30 kg/m²)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hch10)

Across the EU-27 there was little difference between the sexes in terms of the shares of older men and older women who were classified as being obese. In 2017, 21.5 % of older men aged 65-74 years were obese, which was 0.6 percentage points higher than the share for older women of the same age. By contrast, the share of older women aged 75 years that were obese (16.7 %) was some 2.1 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for older men of the same age.

There were 12 EU Member States where a higher share of older women (than older men) were obese in 2017 for both subpopulations (people aged 65-74 years and people aged 75 years or more). This was particularly apparent in the Baltic Member States, the Netherlands, Malta, Poland and Finland. By contrast, a higher proportion of older men were obese (among people aged 65-74 years and people aged 75 years or more) in Luxembourg, Ireland, France, Belgium and Austria.

(% of people whose BMI ≥30 kg/m²)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hch10)

Health limitations among older people

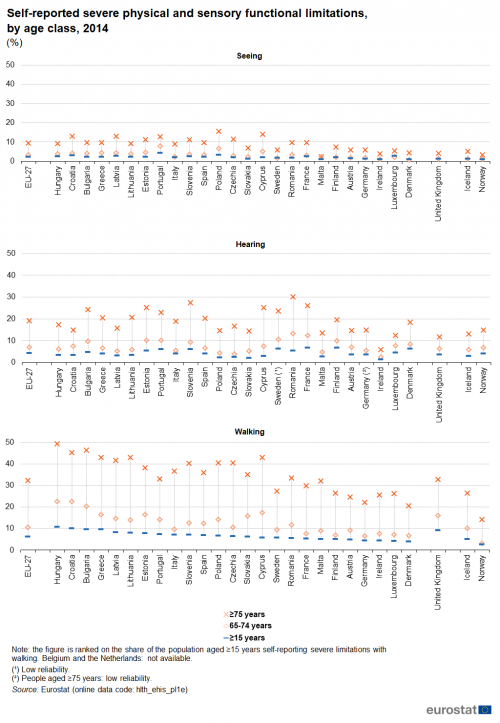

Health is a crucial measure of an individual’s well-being: it is intrinsically tied to aspects of personal independence. The share of the adult population that struggles with daily life — basic activities like eating, bathing and dressing — rises with age. One of the principal reasons behind this pattern is the relatively high share of older people who suffer from physical and sensory functional limitations, impacting on their vision, hearing, mobility, communication or ability to remember (see Figure 17).

Almost one third of people aged 75 years or more had severe difficulties in walking

In 2014, the share of people aged 65-74 years in the EU-27 who had severe difficulty in seeing was only marginally higher, at 3.2 %, than the average for the whole of the adult population (defined here as people aged 15 years or more; 2.2 %). A much higher proportion (9.3 %) of people aged 75 years or more in the EU-27 had severe difficulty in seeing, with this share rising above 12.5 % in Portugal, Croatia, Latvia, Cyprus and Poland.

Similar information for people who reported severe difficulties in hearing reveals that the share of the EU-27 adult population with this sensory functional limitation was 4.2 % in 2014, with higher shares among people aged 65-74 years (7.0 %) and people aged 75 years or more (19.1 %). The share of this latter age group who reported severe difficulties in hearing was at least 25.0 % in Cyprus, Estonia, France, Slovenia and Romania.

Regular (preferably daily) exercise may help prevent elderly mobility issues. Figure 17 shows that in 2014 almost one third (32.3 %) of people aged 75 years or more in the EU-27 reported severe difficulties in walking, while close to one tenth (10.5 %) of people aged 65-74 years faced this limitation. There were 10 EU Member States where the share of people aged 75 years or more who faced difficulties in walking was within the range of 40.0-50.0 %; the highest shares were in Croatia, Bulgaria and Hungary.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_pl1e)

Around one quarter of all older women had severe difficulties in walking

Figure 18 extends the findings of self-reported severe physical and sensory functional limitations by looking at gender differences. In 2014, the share of older women (aged 65 years or more) in the EU-27 who had severe difficulty in seeing was 7.3 %, which was considerably higher than the corresponding share for older men (4.4 %). There was almost no difference in the shares of older men and older women that had severe difficulty in hearing (12.8 % and 12.7 %). However, the most striking difference between the sexes was in terms of the share of older people who had severe difficulty in walking. One quarter (25.0 %) of all older women in the EU-27 reported severe difficulty in walking, while the share for older men was much lower at 15.3 %. This pattern — a higher share of older women reporting severe difficulty in walking — was repeated in each of the EU Member States and was particularly notable in Cyprus (where the difference between the sexes was 19.9 percentage points), Portugal (16.1 percentage points) and Slovenia (15.3 percentage points). More than one third of all older women in Greece, Cyprus, Croatia and Hungary reported severe difficulty in walking, with a peak of 38.7 % in Hungary. The highest shares of older men reporting severe difficulty in walking were recorded in Hungary (25.6 %), Bulgaria (26.8 %) and Croatia (26.9 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_pl1e)

Almost three quarters of people aged 85 years or more had a long-standing illness or health problem

The information presented in Figure 19 complements that already shown in Figure 4 (above), insofar as people who assess their own health as good or very good are unlikely to report that they suffer from chronic morbidity — a long-standing illness or health problem that has lasted for at least six months — while the reverse is also true.

In 2018, almost three quarters (72.5 %) of very old people (aged 85 years or more) in the EU-27 reported that they had a long-standing illness or health problem. This share fell as a function of age: approximately two thirds (66.0 %) of people aged 75-84 years were affected by a long-standing illness or health problem, while the corresponding share for people aged 65-74 years was lower still (55.8 %).

The share of very old people (aged 85 years or more) suffering from a long-standing illness or health problem ranged in 2018 from highs of 97.2 % in Cyprus and 89.7 % in Estonia down to less than half of this age group in Denmark (49.0 %) and Belgium (45.4 %). Note also that Belgium was one of four EU Member State where very old people did not record the highest prevalence of chronic morbidity, with slightly higher shares of self-reported long-standing illness or health problems for people aged 75-84 years in Belgium, the Netherlands, Malta and Sweden.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_04)

A higher proportion of older women than older men reported that they suffered from a long-standing illness or health problem In 2018, the share of older women (aged 65 years or more) in the EU-27 suffering from a long-standing illness or health problem was 62.6 %. This was 3.9 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for older men (58.7 %). This pattern — a higher share of older women (than older men) suffering from a long-standing illness or health problem — was repeated across all but one of the EU Member States; the only exception was France. The gender gap for self-reported suffering from a long-standing illness or health problem peaked at 13.5 percentage points in Romania (with a 58.7 % share among older women compared with a 45.2 % share among older men); Lithuania also recorded a gap in double-digits (10.0 percentage points).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_04)

More than one tenth of people aged 75 years or more reported severe difficulties preparing meals

Figure 21 shows in more detail some of the (self-reported) difficulties that are faced by people aged 75 years or more in their everyday lives. In 2014, almost two fifths (39.2 %) of these older people in the EU-27 had severe difficulties doing occasional heavy housework [1] during the 12 months preceding the survey, with a higher share for older women (45.9 %) than older men (27.9 %). This pattern was repeated for each of the household and personal care activities presented in Figure 21, with a higher proportion of older women (than older men) reporting severe difficulties. Note that women have greater longevity than men and are hence more likely to be living alone and more likely to be frail, which could have an impact on the frequency with which older men and older women undertake some of these activities. More than one tenth of all people (both sexes) aged 75 years or more in the EU-27 had severe difficulties managing medication (10.4 %), preparing meals (13.8 %), bathing and showering (14.3 %), taking care of finances and everyday administrative tasks (17.1 %) or doing light housework [2] (18.6 %), with this share rising to more than one fifth for shopping (23.2 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_ha1e) and (hlth_ehis_pc1e)

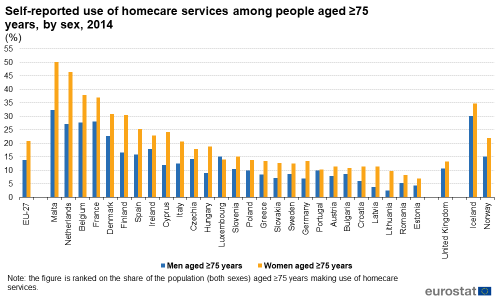

One fifth of women aged 75 years or more made use of homecare services

The relatively high proportion of people aged 75 years or more in the EU-27 facing severe difficulties in carrying out a range of everyday tasks suggests that there is considerable demand for the provision of homecare services [3] that can alleviate such issues and make it possible for older people to remain independent for longer (rather than moving into residential, long-term, or institutional-based nursing and care homes); these (professional) services are expected to become increasingly important in the coming years.

In 2014, some 18.1 % of all persons aged 75 years or more in the EU-27 reported that they had made use of homecare services during the 12 months preceding the survey. The share of older women (20.8 %) making use of these services was higher than the corresponding share for older men (13.9 %); this pattern was repeated in all but one of the EU Member States and was particularly strong in Latvia and Lithuania, where older women were three to four times as likely as older men to make use of homecare services. Luxembourg was the only exception, as a slightly higher share of older men (15.1 %) compared with older women (14.0 %) made use of homecare services. The provision and organisation of homecare services varies considerably between EU Member States and this is reflected in the use of such services: while at least one third of people aged 75 years or more reported using homecare services in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Malta, this share was less than one tenth in the Baltic Member States, Croatia and Romania.

It is also worth considering that while some older people receive homecare services, others are providers of similar services — for example, looking after other elderly people or looking after grandchildren — more information on this is provided in Chapter 6.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_am7e)

Use of doctors, medicines and health services among older people

Older people are more likely to consult both general and surgical practitioners

As people age, it might be expected that they need more frequent visits to consult both general practitioners and surgical practitioners. Figure 23 confirms that this is true: in 2017, approximately three quarters (76.4 %) of the EU-27 adult population (defined here as people aged 16 years or more) had consulted a general practitioner during the 12 months preceding the survey. The share was higher for people aged 65-74 years (86.7 %) and peaked among people aged 75 years or more (92.0 %).

In 2017, almost all (97.4 %) people aged 75 years or more in Denmark had consulted a general medical practitioner during the 12 months preceding the survey, while there were seven further EU Member States where this share was at least 95.0 %. By contrast, the lowest consultation rates were recorded in Bulgaria, Finland and Sweden (all below 80.0 %).

While people were generally less likely to have consulted a surgical practitioner (compared with a general practitioner), a similar pattern was observed, insofar as older people (aged 75 years or more) were again more likely than younger generations to have consulted this type of doctor. In 2017, almost three quarters (74.0 %) of people aged 75 years or more in the EU-27 had consulted a surgical practitioner during the 12 months preceding the survey; the highest consultation rate for this age group was recorded in Germany (90.4 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hch03)

The differences between the shares of older men and older women (aged 75 years or more) in the EU-27 who consulted a general or a surgical practitioner were relatively small. In 2017, a slightly higher share of older women (92.3 %) than older men (91.5 %) consulted a general practitioner during the 12 months preceding the survey. The situation was reversed for consulting a surgical practitioner: just over three quarters (75.4 %) of older men consulted this type of doctor in the 12 months preceding the survey, which was 2.4 percentage points higher than the corresponding share recorded among older women (73.0 %).

The share of older women that consulted a general practitioner in Estonia (88.2 %) was considerably higher than for older men (81.7 %); this was the largest gap (6.5 percentage points) between the sexes across the EU Member States. This pattern was repeated for consulting a surgical practitioner, as the share of older women (63.8 %) consulting this type of doctor in Estonia during the 12 months preceding the survey was 5.9 percentage points higher than the share for older men (57.9 %). By contrast, in Slovenia the share of older men (92.5 %) that consulted a general practitioner was 6.0 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for older women (86.5 %), while the share of older men (52.1 %) that consulted a surgical practitioner in Malta was 8.3 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for older women (43.8 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hch03)

Some 87 % of people aged 75 years or more used prescribed medicines

In a similar manner, older people also made a greater use of prescribed medicines (see Figure 25). In 2014, just less than half (48.1 %) of the EU-27 adult population (defined here as people aged 15 years or more) reported that they made use of prescribed medicines during the two weeks preceding the survey interview. This share rose with age and peaked among people aged 75 years or more, at 87.0 %. The use of prescribed medicines by older people aged 75 years or more across the EU Member States ranged from a low of 68.0 % in Romania up to a high of 96.3 % in Czechia.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_md1e)

The share of older women (aged 65 years or more) in the EU-27 reporting that they made use of prescribed medicines during the two weeks preceding the survey interview was 83.5 % in 2014. This was 3.4 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for older men (80.1 %). Luxembourg was the only EU Member State where a higher share of older men (89.0 %) made use of prescribed medicines; the corresponding share among older women was 86.6 %. By contrast, the share of older women reporting that they made use of prescribed medicines was 8.8-13.2 percentage points higher than the share among older men in the Baltic Member States — the three largest gender gaps in the EU.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_md1e)

Around half of all people aged 75 years or more had been vaccinated against influenza

Influenza occurs each winter in the EU, although the intensity and strain of the infection varies from year to year. While it is an unpleasant experience for a majority of the population, influenza can potentially develop into a far more serious illness for specific groups of society. People aged 65 years or more are considered one such ‘high-risk’ group, especially when they also suffer from a chronic disease.

In 2014, around half (49.6 %) of all people aged 75 years or more in the EU-27 reported that they had been given a vaccination against influenza during the 12 months preceding the survey; the share for people aged 65-74 years was lower, at 34.9 %. Across the EU Member States, the Netherlands (82.1 %) had the highest vaccination rate for influenza among people aged 75 years or more, while there were 11 additional Member States where a majority of this age group had received an influenza vaccination during the 12 months preceding the survey. At the other end of the range, vaccination rates were less than 5 % for people aged 75 years or more in Bulgaria and the Baltic Member States (with a low of 0.9 % in Estonia).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_pa1e)

High blood pressure, arthrosis and back problems were the most common chronic diseases reported by older people

Despite the best intentions, regular check-ups and screenings cannot prevent the onset of chronic illness for some older people; the prevalence of such diseases usually increases with age. Chronic diseases can restrict the independence of older people and may require considerable health and social resources for care and/or treatment.

Figure 28 shows some of the most common chronic diseases for older people in the EU-27. In 2014, more than half (53.3 %) of all people aged 75 years or more suffered from high blood pressure during the 12 months preceding the survey, while relatively high shares of people in this age group suffered from arthrosis (47.9 %) and back problems (41.2 %).

In 2014, it was common to find that a higher proportion of women (rather than men) aged 75 years or more in the EU-27 suffered from chronic diseases. This was particularly notable for arthrosis, back and neck problems, high blood pressure, and chronic depression. There were some chronic diseases that affected a higher proportion of older men, although differences between the sexes were relatively small. Among others, these included heart attacks, chronic lower respiratory diseases and diabetes.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_cd1e)

A relatively high share of people aged 75 years or more reported depressive symptoms

A range of common mental health disorders — depression, anxiety, panic attacks or phobias — may be linked to pressure at work, the stresses of everyday life, or loneliness. Figure 29 shows self-reported depressive symptoms among older people, by age and by sex. In 2014, some 7.1 % of people aged 55-64 years in the EU-27 had depressive symptoms during the 12 months preceding the survey, this share was lower (6.5 %) among people aged 65-74 years (when the majority of older people were already in retirement), but higher (13.1 %) among people aged 75 years or more (when there was an increased risk of living alone, losing personal independence and facing mobility issues).

This pattern — the highest share of depressive symptoms being recorded for people aged 75 years or more — was repeated in all but two of the 25 EU Member States for which data are available; the exceptions were Finland (where the highest prevalence of depressive symptoms was recorded among people aged 55-64 years) and Austria (where the highest share was recorded among people aged 65-74 years).

Older women aged 75 years or more were more prone (than older men) to experience depressive symptoms. In 2014, 15.8 % of women in this age group reported depressive symptoms, compared with a 9.2 % share among men of the same age; note than older women are more likely to be living alone than older men. Older women were much more likely than older men to report depressive symptoms in the southern EU Member States of Cyprus, Spain and Portugal, while Romania, Ireland, Finland and Austria were the only Member States where a higher share of older men reported depressive symptoms.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_mh1e)

Very old people were more likely to visit hospital as an in-patient rather than as a day patient

A hospital discharge occurs when a hospital patient is formally released after an episode of care. The reasons for discharge include finalisation of the patient’s treatment, signing out against medical advice, a transfer to another healthcare institution, or death.

In 2018, older people were more likely than the population as a whole to be discharged from hospital; Figure 30 shows that this pattern held for in-patients in all 24 of the EU Member States for which data are available. The share of very old people (aged 85 years or more) being discharged from in-patient care was almost six times as high as the national average for the whole population in Finland and was 4.5-5.0 times as high in Malta (2017 data), Sweden, Cyprus and Luxembourg (2016 data). Equally, the share of very old people being discharged as in-patients was higher than the corresponding share for people aged 65-84 years in each of the Member States except for Romania.

Older people aged 65-84 years were more likely than the national average to be discharged from hospital after day care treatment in 2018. It was common to find that a higher share of people aged 65-84 years — compared with people aged 85 years or more — were discharged after day care treatment, perhaps reflecting mobility issues or the severity or nature of medical conditions among the very old; the only exceptions were Denmark (2016 data), Sweden and Germany (2017 data).

(index, number of hospital discharges per 100 000 inhabitants in the whole population = 100)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_disch4) and (hlth_co_disch2)

A relatively high share of older women aged 75 years or more had unmet needs for medical examination

The share of older people reporting unmet needs for medical examination aims to capture the subjective difficulties faced by respondents, on at least one occasion during the 12 months preceding the survey, to receive medical care which they required. Figure 31 shows that older people in the EU-27 generally faced greater difficulties in accessing medical services (than the adult population as a whole — defined here as people aged 16 years or more) which may, at least in part, reflect higher levels of demand for medical services among older people. In 2018, the cost of medical services and waiting lists were the two principal issues that led to unmet needs for medical examination among both sexes and all age groups, but in particular among women aged 75 years or more.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_08)

Causes of death among older people

Defining the cause of death

A cause of death is defined as the disease or injury which started the train (sequence) of morbid (disease-related) events which led directly to death, or the circumstances of the accident or violence which produced the fatal injury. This information may be used by health authorities to help determine the focus of their public actions (for example, where to launch health information programmes to prevent illness/disease, or where to increase/decrease health expenditure).

Diseases of the circulatory system were the most common cause of death among people aged 75 years or more

As already shown in Chapter 1, women can expect to live longer than men; this is also borne out when studying the information presented in Figure 32. In 2016, the principal causes of death among people aged 55 years or more in the EU-27 were diseases of the circulatory system, cancer and diseases of the respiratory system. Cancer was the main cause of death both for men and for women between the ages of 55 and 74 years. From the age of 75 years onwards, the most common cause of death was diseases of the circulatory system.

In 2016, more men than women in the EU-27 died from the six principal causes of death that are highlighted in Figure 32; this pattern was repeated for each of five-year age groups between 55 and 79 years. Unsurprisingly therefore, the overall number of men still alive after the age of 80 was considerably lower than the total number of women that were still alive. After the age of 80, these six causes of death accounted for more female (than male) deaths, reflecting changes in population structure and the higher number of women still alive. The difference was particularly pronounced for the final age category, as the total number of deaths (from these causes) among very old women aged 95 years or more was 3.3 times as high as the corresponding figure for very old men, as far fewer men had experienced such longevity.

The crude death rate is an alternative measure based on the number of deaths per 100 000 inhabitants. EU-27 crude death rates were higher for men than for women for each of the six main causes of death shown in Figure 32 and this pattern was repeated for most age categories. The only exceptions were: crude death rates for women aged 90-94 years and 95 years or more were higher than those for men of the same age for diseases of the nervous system and sense organs and for mental and behavioural disorders; the crude death rate for women aged 95 years or more was higher than that for men of the same age for diseases of the circulatory system.

(number of deaths)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_cd_aro)

The standardised death rate for men aged 65 years or more for cancer was almost twice as high as that for women

Standardised death rates are adjusted to reflect differences in population structures. As most causes of death vary significantly with people’s age and sex, the use of standardised death rates improves comparability over time (and between countries) with the results adjusted to reflect a standard age distribution.

In 2016, EU-27 standardised death rates for older men (aged 65 years or more) were consistently higher than those for older women for each of the 10 main causes of death. Standardised death rates of older men for cancer (1 390 deaths per 100 000 male inhabitants) and for diseases of the respiratory system (503 deaths per 100 000 male inhabitants) were almost twice as high as those for older women (738 and 257 deaths per 100 000 female inhabitants). By contrast, there was almost no difference between the sexes in terms of standardised death rates for mental and behavioural disorders.

(per 100 000 male/female inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_cd_asdr2)

More than two fifths of women aged 65 years or more died from diseases of the circulatory system

In 2016, more than two fifths (43.3 %) of all deaths among older women (aged 65 years or more) in the EU-27 were attributed to diseases of the circulatory system, while the share for older men was lower (36.8 %). By contrast, more than one quarter (28.1 %) of all deaths among older men in the EU-27 were attributed to cancer, while the share for older women was lower (19.3 %).

Figure 34 provides a more detailed picture based on standardised death rates, taking account of differences in population structures between EU Member States; it shows information for the two principal causes of death within the EU. In 2017, standardised death rates for older men (aged 65 years or more) were consistently higher than for older women in each of the EU Member States both for diseases of the circulatory system and for cancer. For every 100 000 older male inhabitants in Bulgaria, Latvia and Lithuania, there were more than 6 000 deaths caused by cancer or diseases of the circulatory system. In a similar vein, for every 100 000 older female inhabitants in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania, there were more than 4 000 deaths caused by cancer or diseases of the circulatory system.

(per 100 000 inhabitants aged ≥65 years)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_cd_asdr2)

Source data for tables and graphs

Notes

- ↑ Walking with heavy shopping for more than five minutes, spring cleaning, scrubbing floors with a scrubbing brush, vacuum cleaning, cleaning windows, or other similar heavy housework.

- ↑ Washing dishes, ironing, bed-making and childcare.

- ↑ Includes help with daily tasks such as meal preparations, house-keeping, shopping, medication reminders or transportation.

Direct access to

Online publications

- Ageing Europe — looking at the lives of older people in the EU

- Health in the European Union — facts and figures

- Disability statistics

Categories of articles

- Health (t_hlth), see:

- Health status (t_hlth_state)

- Health care (t_hlth_care)

- Causes of death (t_hlth_cdeath)

- Mortality (t_demo_mor)

- Life expectancy at birth by sex (tps00205)

- Life expectancy at age 65, by sex (tps00026)

- Mortality (t_demo_mor)

- Health (hlth), see:

- Health status (hlth_state)

- Health determinants (hlth_det)

- Health care (hlth_care)

- Disability (hlth_dsb)

- Causes of death (hlth_cdeath)

- Mortality (demo_mor), see:

- Deaths by age and sex (demo_magec)

- Life expectancy by age and sex (demo_mlexpec)

- Life expectancy by age, sex and educational attainment level (demo_mlexpecedu)

Metadata

- Health care resources (ESMS metadata file — hlth_res)

- Health care activities (ESMS metadata file — hlth_act)

- European health interview survey (EHIS) (ESMS metadata file — hlth_det)

- Causes of death (ESMS metadata file — hlth_cdeath)

- Mortality (ESMS metadata file — demo_mor)

Further methodological information