World direct investment patterns

Data extracted in July 2023.

Planned article update: August 2024.

Highlights

In 2021, Europe was the largest location of foreign direct investment stocks in the world, accounting for more than one-third (36 %) of the world's inward investment positions.

In 2021, Europe was the leading outward investor in the world, accounting for more than two-fifths (42 %) of the world's outward investment stocks.

(% of total)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_pos) and UNCTAD (FDI/MNE database)

Globalisation patterns in EU trade and investment is an online Eurostat publication presenting a summary of recent European Union (EU) statistics on economic aspects of globalisation, focusing on patterns of EU trade and investment.

In an attempt to remain competitive, modern-day business relationships extend well beyond international trade in goods and services. Indeed, there is a growing reliance upon different forms of industrial organisation including: foreign affiliates, overseas investment, mergers, joint ventures, subcontracting, offshoring or licensing agreements. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is one such economic strategy and it is the subject of this article.

Some economists argue that, compared with international trade, FDI creates deeper links between economies, thereby stimulating technology transfers and fostering the exchange of know-how, which in turn drives productivity and makes economies more competitive. Governments often use economic arguments as a reason for seeking to attract FDI, based on the premise that it can help generate economic growth and provide jobs.

On the other hand, other economists provide a range of counter arguments, highlighting the role played by some multinational enterprises in 'stripping' resources or exploiting lower labour and environmental standards in host economies. Furthermore, there is also a considerable amount of literature around corporate responsibility, ethics and tax-optimisation or avoidance techniques that may be adopted by multinational enterprises. As such, there remains a sizeable debate over the motives and redistributive effects of FDI.

Data for the world and non-EU countries have been converted from United States dollars to euro. Annual average exchange rates have been used for FDI flows and end-of-year rates for FDI stocks (positions).

Full article

Statistics on foreign direct investment

Statistics on foreign direct investment

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is an investment made by a resident enterprise in one economy (direct investor or parent enterprise) with the objective of establishing a lasting interest in an enterprise that is resident in another economy (direct investment enterprise). This implies the existence of a long-term relationship between the direct investor and the direct investment enterprise, as well as the ability to exercise some form of control/influence over business decisions. Indeed, this effective voice in the management of the foreign enterprise is one of the principal differences between FDI and other forms of investment, such as portfolio investment (where the investor does not seek control the foreign enterprise) or other assets (for example, intellectual property rights).

FDI data are based on international standards: since 2013, these data follow the standards laid out in the IMF's Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, 6th edition (BPM6) and the OECD's Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct Investment, 4th edition (BD4). Within the financial account of the balance of payments, a positive sign represents an increase in an asset or a liability to which it relates, while a negative sign represents a decrease. Therefore, a plus sign denotes a net increase in financial assets or liabilities, while a minus sign refers to a net decrease in financial assets or liabilities.

There are four broad types of FDI: i) the creation of productive assets, for example, establishing a new plant/office abroad (so-called 'greenfield investment'); ii) the purchase of existing assets abroad through acquisitions, mergers or takeovers ('brownfield investment'); iii) the extension of capital, which relates to additional investments being made to expand an established business; and iv) financial restructuring, which refers to investments for debt repayment or loss reduction.

Important: note that the data presented for the EU include special purpose entities (SPEs), while those for the rest of the world exclude SPEs (see article on Foreign direct investment – intensity ratios for more information). Time series for the EU and its Member States excluding SPEs are only available, at the time of writing, for the period since 2013 and hence in order to avoid a break in series the information presented systematically include SPEs. From an economic standpoint, the inclusion of SPEs may distort the geographic distribution of FDI statistics as it can appear that countries receive or make investments when in reality the funds are simply being passed through holding companies and other similar structures. For this reason, statistics excluding SPEs should generally be preferred for economic analyses of FDI, as they remove those flows of FDI that have little or no impact on 'real' economies. On the other hand, as part of the balance of payments, the inclusion of SPEs should generally be favoured insofar as the main objective for this type of analyses is to measure all (direct) cross-border monetary transactions, irrespective of whether these are through SPEs or not.

Stocks of foreign direct investment

In 2021, Europe accounted for 42 % of the world's outward investment positions

The international investment position of a country details its stock of financial assets and liabilities; for the purpose of this publication these stocks are measured at the end of each year (although more detailed statistics are collected at the end of each quarter). FDI stocks reflect the accumulated value held at the end of the reference period, reflecting the value of stocks at the start of the year, adjusted for any transactions (flows) which take place during the year and any changes in the value of positions other than transactions (for example, revaluations due to exchange rates or other price changes).

In 2021, the global stock of FDI was valued at €38.5 trillion (€38 500 billion), based on an average of inward and outward positions. Europe was the largest source and destination of FDI stocks in the world. According to the United Nations, more than one-third (36.2 %) of global inward investment was located in Europe (€14.5 trillion), while it accounted for more than two-fifths (42.2 %) of the world's outward investment stocks (some €15.6 trillion).

Between 2011 and 2021, Northern America was an increasingly attractive location for foreign investment

There was a relatively strong decline between 2011 and 2019 in the share of global FDI stocks that were located in Europe, its share of the world total falling by 6.2 percentage points (pp). However, there was a considerable change in 2020, in part reflecting the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, as investment stocks in Europe grew rapidly – the share of Europe rose 2.8 pp between 2019 and 2020. However, the long-term development returned in 2021, as Europe's share dropped to 36.2 %, slightly below the 2019 share and 6.4 pp below the 2011 share. The fall between 2011 and 2021 in the share of global FDI stocks that were located in Europe was the largest fall recorded in any of the continents over this period.

The share of FDI stocks located in Latin America and the Caribbean also fell (down 3.0 pp between 2011 and 2021), and falls were also recorded in Oceania, Africa and Asia, although the size of their falls were less. By contrast, the share of global direct investment in Northern America increased, up 12.0 pp.

Europe's outward stocks of FDI were greater than the value of inward FDI stocks held by the rest of the world within Europe; as such, Europe was a net investor. Asia was the only other continent that reported being a net investor. The second part of Figure 1 shows that there were relatively large fluctuations concerning Europe's share of the world's outward FDI stocks between 2011 and 2021. This proportion started at 50.7 % in 2011, in the aftermath of the global financial and economic crisis, in other words, at more than half of the global total. This share fell for six successive years to 43.0 % by 2017 and then remained between 42.6 % and 45.1 % through until 2020. The EU's share of the world's outward FDI stocks fell in 2021, down to 42.2 %, its lowest level during the period under consideration.

Northern America had the second highest share (28.9 %) of the world's outward FDI stocks in 2021, closely followed by Asia (24.9 %). Between 2011 and 2021, Europe's share declined greatly (down 8.5 pp), while there was a smaller decrease observed for Oceania, as well as for Latin America and the Caribbean; Africa's share was similar in 2021 to what it had been in 2011. By contrast, there were relatively sizeable increases in the shares of outward FDI from Asia (up 6.4 pp) and Northern America (up 3.1 pp).

(% of world total)

Source: UNCTAD (FDI/MNE database)

Stocks of foreign direct investment represent about one-third of the world's annual economic output

Figure 2 presents information on the relative importance of FDI stocks compared with the economic size of each economy (as measured by annual gross domestic product (GDP)). The global average in 2021 for the ratio of outward direct investment stocks to GDP was 44.9 %, while the ratio of inward direct investment stocks to GDP was 48.8 %.

In 2021, two Asian economies – Hong Kong and Singapore – reported particularly high degrees of 'openness', insofar as inward FDI stocks in both these reporting economies were valued considerably higher than their levels of GDP; the values of direct investment stocks in Hong Kong and Singapore were 5.7 and 4.9 times as high as their GDP, respectively. In all of the remaining economies presented in Figure 2, the value of inward FDI stocks was less than the economic output of the country / geographical aggregate concerned; the next highest share was recorded in the United Kingdom (with inward FDI stocks representing 88.1 % of GDP).

Direct investment stocks in the EU were valued at 52.0 % of GDP in 2021, which was somewhat higher than the global average. Aside from Hong Kong, Singapore and the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States were the only other global competitors (among those shown in Figure 2) that recorded a higher ratio than the EU. By contrast, stocks of inward FDI relative to GDP were much lower in the Chinese (12.1 %) and, in particular, the Japanese (5.4 %) economies. The relatively low overall level of inward FDI stocks in Japan resulted from an absence of foreign investment in most activities, aside from the manufacture of machinery and motor vehicles.

Most 'open' economies have considerable stocks of both inward and outward investment

Reversing the analysis and considering the relative importance of outward stocks of FDI from each economy, a general pattern emerges whereby many of those countries which were 'open' to a high degree of market penetration in the form of inward FDI were also found to have high ratios of outward FDI relative to GDP. This supports a view that some economies seek to gain a competitive advantage by encouraging free trade and investment opportunities, whereas other countries are more inward-looking.

Nevertheless, there were some exceptions: for example, the ratio of stocks of direct investment abroad relative to GDP for Japan was 41.4 % (much higher than the ratio of inward FDI stocks relative to GDP) – suggesting that while it was relatively commonplace for Japanese enterprises to invest in foreign plants, it was far less common for foreign enterprises to invest in Japan. A similar pattern was observed in Canada, where the ratio of outward stocks of FDI relative to GDP was 119.2 % (in other words, outward investment was valued higher than the size of the Canadian economy), and also in South Korea (where outward investment was more than double the size of inward investment). By contrast, the value of stocks of direct investment abroad from Mexico, India, Türkiye and Brazil was relatively low (both in relation to GDP and in relation to the value of stocks of inward investment in each of these economies). These differences between ratios for inward and outward stocks of FDI may be used to identify which economies were net investors in 2021; this was the case for Japan, South Korea, Canada, South Africa, the United Arab Emirates, China, the EU and Hong Kong,

(%)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_pos) and (nama_10_gdp) and UNCTAD (FDI/MNE database)

Multinational enterprises

A wide range of factors may influence an enterprise's decision as to whether to (re)locate (some) production abroad, including the size and distance of the foreign market, its growth prospects, wage and productivity levels, or regulatory and legal regimes. However, investment decisions are often focused on profits. As the relative price of transport and communications fell, it became considerably easier for multinational enterprises to consider moving their production locations across the globe, for example, to benefit from cost savings that may be linked to lower labour costs or local resource endowments of raw materials. In a similar vein, the provision of some services has also been affected, as witnessed by the concentration of call centres / helpdesks and software developers in some countries. Furthermore, FDI provides enterprises with the possibility of accessing protected and regulated service markets through the establishment of a commercial presence in the host economy.

Table 1 provides details relating to the size of the top 20 non-financial multinational enterprise groups in the world in terms of their foreign assets. The information comes from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Half (5 out of the top 10) of the world's leading multinational enterprise groups (in terms of foreign assets) in 2022 had their headquarters in the EU: TotalEnergies SE (France) was specialised in energy activities, the Volkswagen Group (Germany) and Stellantis NV (the Netherlands) were specialised in the manufacture of motor vehicles, Deutsche Telekom AG (also Germany) was specialised in information and communication services, while Anheuser-Busch InBev NV (Belgium) was specialised in the manufacture of beverages (principally the brewing of beer).

Looking across the whole of the top 20 non-financial multinational enterprises, eight were located in the EU (three in Germany, two from France and one in each of Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands), four were from the United Kingdom, three from the United States, three from Japan, leaving a single multinational from each of China and Hong Kong.

The share of foreign assets in total assets was generally very high for most multinationals shown in Table 1, accounting for more than four-fifths of all assets in half (10 out of the top 20). However, more than half of all assets were in the domestic economy for five of the non-financial multinationals – Exxon Mobil Corporation (52.3 %), Volkswagen Group (57.6 %), EDF SA (60.8 %), Microsoft Corporation (64.0 %) and China National Petroleum Corp (79.0 %).

Source: UNCTAD (World Investment Report 2022)

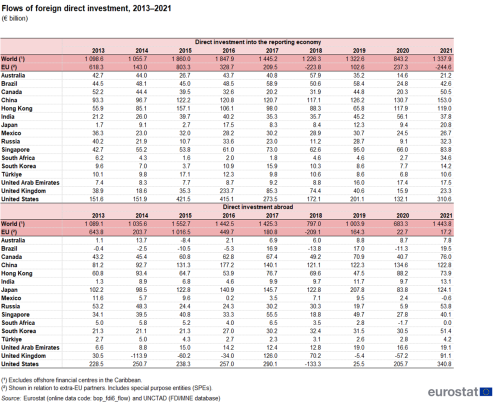

The stock of foreign investment in the United States more than trebled between 2013 and 2021

Developments for both inward and outward stocks of FDI are shown in Table 2. There were six countries where the nominal value of inward FDI stocks more than doubled between 2013 and 2021; the highest growth rates were recorded by the United States (where the value more than trebled), India, Singapore, China, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom.

The pace of change was even more rapid concerning the level of Chinese investment stocks abroad: in 2021, outward FDI stocks from China were valued at 4.8 times as high as they had been in 2013. It should be noted that the total value of these stocks had been, in 2013, still relatively small (compared with the levels recorded in the EU or the United States). The next highest growth rates for outward FDI stocks were recorded for the United Arab Emirates, South Korea, Singapore and Canada.

(€ billion)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_pos) and UNCTAD (FDI/MNE database)

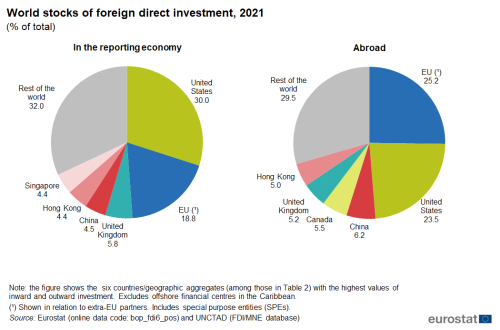

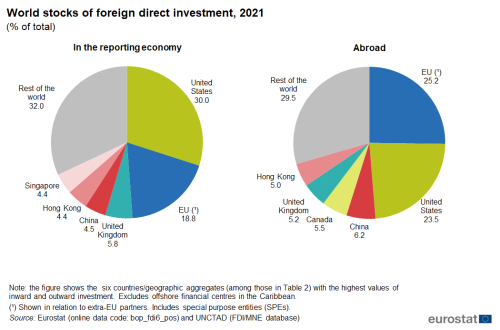

The final presentation of information concerning inward and outward stocks of FDI describes the share of world stocks between the leading global players (see Figure 3). In 2021, just under one-fifth (18.8 %) of global inward investment stocks were located in the EU; its share of global outward investment was somewhat higher, reaching 25.2 %. The EU recorded the highest share of outward stocks of FDI in 2021 and the second highest share of inward stocks; the reverse situation – highest inward stocks and second highest outward stocks – was observed in the United States. The United Kingdom accounted for the third highest share of global FDI stocks for inward investment, while China had the third highest share for outward investment.

(% of total)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_pos) and UNCTAD (FDI/MNE database)

Foreign direct investment flows

FDI flows comprise capital provided by a foreign direct investor to an FDI enterprise, or capital received from an FDI enterprise by a foreign direct investor. These flows are composed of three components: equity capital, reinvested earnings and intra-company loans. Global flows of FDI were valued at €1 331 billion in 2021, based on an average of inward and outward flows.

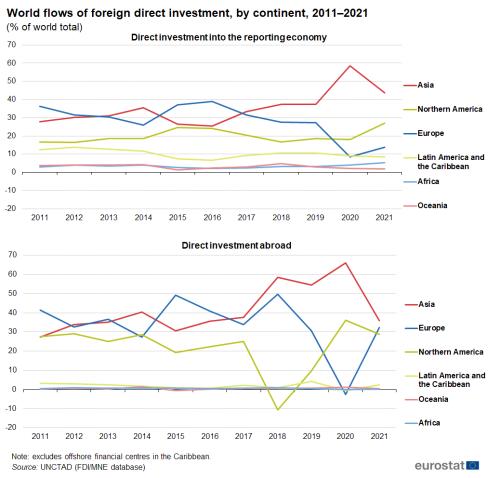

In 2021, Europe was the world's second largest source of foreign direct investment, behind Asia, and third largest recipient behind Asia and Northern America

Figure 4 shows the share of global flows of FDI accounted for by each continent during the period 2011–2021. Note the sudden change in the geographical structure of investment flows between 2019 and 2020 and again between 2020 and 2021 that may be attributed, at least in part, to the COVID-19 crisis; this reflects not only the spread and intensity of the pandemic itself but also the economic/cultural differences in how governments and businesses reacted to the pandemic. There was a dramatic overall fall in global inward investment flows in 2020 (down 36.2 %), while outward flows fell somewhat less (down 31.9 %). The recovery in 2021 was stronger in terms of outward flows (up 111.3 %) than inward flows (up 58.7 %). Geographically, the share of flows into and out of Asia increased greatly in 2020, while the shares into and out of Europe fell greatly; in 2021, this pattern was largely reversed.

Over the longer-term, inward investment followed a fluctuating pattern of developments coupled with a restructuring of investment flows with less directed towards Europe and more towards other continents, particularly Asia. A similar pattern was observed for outward investment. Europe's share of the world's outward investment fell from 41.3 % in 2011 to 27.3 % in 2014. It rebounded to 49.7 % by 2018. At the start of the COVID-19 crisis (in 2020), it turned negative, down to -2.6 %, but grew to 32.3 % in 2021. FDI inflows into Europe were valued at €185 billion in 2021 while Europe's outflows of FDI were much larger at €466 billion.

While the European share of world FDI flows was considerably lower in 2021 than in 2011, Asia saw an increase in its respective shares; this was particularly the case in 2020. While global investment flows generally plummeted in 2020, inward flows to Asia were almost stable (down 0.2 %). For comparison, outward flows from Asia fell 17.6 %. As a result, Asia attracted a majority (58.4 %) of global inward investment flows in 2020 and provided close to two-thirds (66.0 %) of the world's outward flows. These shares dropped considerably in 2021:

- back to 43.6 % for inward flows, which was nevertheless higher than the shares in any year from 2011 to 2019;

- to 35.8 % for outward flows, in line with the shares recorded between 2012 and 2017.

(% of world total)

Source: UNCTAD (FDI/MNE database)

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, developments for FDI flows were quite irregular (similar to the pattern observed for international trade in goods). Very large increases in investment flows were observed in 2015 and 2021. By contrast, there were relatively large falls in global investment flows in 2017, 2018 and (after the onset of the pandemic) 2020.

Developments observed in the levels of global FDI flows are often strongly influenced by particularly large changes observed for just one or two countries / geographical aggregates. For example, looking at inward flows, the large increase observed in 2015 reflected very large changes in the level of FDI flows reported by the EU and the United States, while the large decrease observed in 2017 reflected very large changes in the level of FDI flows reported by the EU, the United Kingdom and the United States. Concerning movements in outward flows, the large increase in 2015 mainly reflected changes reported for the EU, while the large decrease observed in 2018 reflected changes for the EU, the United States and (to a lesser degree) the United Kingdom. The fall in 2020 and increase in 2021 were exceptions, as decreases were observed in a majority of economies in 2020 and increases in a majority in 2021.

FDI flows entering the United States were considerably higher in 2021 than they had been in 2013

Among the economies presented in Table 3, the highest increases in absolute terms for inward flows of FDI between 2013 and 2021 concerned investment in the United States, Hong Kong, China, Singapore and South Africa (with increases in the range of €28.3–159.0 billion). By contrast, the highest relative growth was recorded in Japan, as its inward flows of FDI in 2021 were 12.0 times as high as in 2013, although they remained relatively low in absolute terms (€20.8 billion). Among the remaining countries, South Africa, the United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong and the United States recorded inward flows of FDI in 2021 that were at least twice as high as they had been in 2013.

Between 2013 and 2021, China and Hong Kong became increasingly important investors in the global economy

The highest increases in absolute terms for outward flows of FDI between 2013 and 2021 concerned investment from the United States (which was €112.4 billion higher in 2021 than in 2013). By contrast, the highest relative growth rates were recorded for India and Australia, as their outward flows of FDI in 2021 were 10.4 and 7.2 times, respectively, as high as in 2013, although they remained relatively low in absolute terms (€13.1 billion and €7.8 billion). Most of the remaining economies also recorded higher outward flows of FDI in 2021 than in 2013, the exceptions being the EU, South Africa, Mexico and Brazil.

Another interesting aspect of the information presented in Table 3 is the rapid transformation of the balance between inward and outward flows of FDI to/from China. While the level of direct investment into and from the Chinese economy was relatively balanced in 2014, 2018, 2019 and 2020, outward flows clearly exceeded inward flows in 2015, (most notably) 2016 and 2017, while inward flows exceeded outward flows in 2013 and 2021. As a sign of its growing global importance, outward Chinese investment exceeded the level recorded for Japan in 2015, 2016 and 2020.

Geopolitical concerns may also impact on the development of investment flows. For example, there was a considerable decrease in flows of inward and outward investment to and from Russia between 2014 and 2015, reflecting the introduction of economic sanctions and restrictions on access to capital markets for the Russian banking sector (which may have impacted this sector in the form of capital flight). Inward flows to Russia increased substantially in 2021, whereas outward flows were negative.

(€ billion)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_flow) and UNCTAD (FDI/MNE database)

In 2021, the United States was the world's largest outward investor and also the largest recipient of inward investment

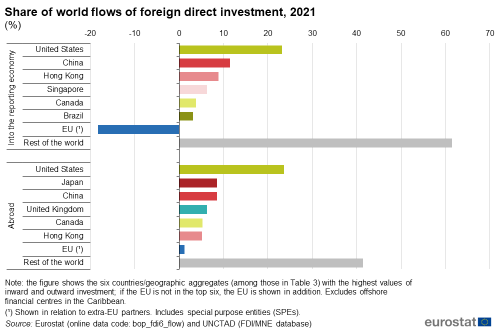

Among the economies studied, the United States was the host economy that received the highest value of inward FDI in 2021, with a 23.2 % share of the world total (see Figure 5). Just over one-tenth (11.4 %) of the world's FDI flowed into China and somewhat less than one-tenth (8.9 %) into Hong Kong. The value of inward FDI in the EU in 2021 was negative, due to disinvestment exceeding new investment.

In 2021, the United States was also the leading outward investor among the economies studied, accounting for nearly one quarter (23.6 %) of the world's FDI flows abroad. The next highest shares were observed for Japan (8.6 %) and China (8.5 %). The value of outward FDI from the EU in 2021 was equivalent to 1.2 % of the world total.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_flow) and UNCTAD (FDI/MNE database)

Source data for tables and graphs

Direct access to

- Globalisation patterns in EU trade and investment (Chapters 4 and 5)

- Balance of payments

- Balance of payments – International transactions (BPM6) (ESMS metadata file – bop_6_esms)