Urban-rural Europe - women and men living in rural areas

Data extracted: October 2022.

Planned article update: December 2024.

Highlights

Older women (aged 65 years or over) accounted for almost a quarter (24.9 %) of the female population in the EU's predominantly rural regions in 2021.

In 2021, just over two thirds (67.3 %) of all women of working age (20–64 years) living in rural areas of the EU were in employment; the employment rate for men living in rural areas was considerably higher, at 79.6 %.

Equality between women and men has always been acknowledged as one of the core values of the European Union (EU). It was recognised in the Treaty of Rome and during the intervening 65 years EU legislation has reinforced these values. Article 21 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union states that any discrimination based on gender, among other forms of discrimination, is prohibited.

Some women living in rural areas have more limited access (than men) to services, rural organisations, productive infrastructure and technology. In some cases, female achievements may be undervalued or not recognised; sometimes referred to as ‘invisible labour’ (for example, when providing family labour input for agricultural holdings or carrying out a wide range of household chores). Other women may face difficulties in finding/maintaining suitable, stable paid employment. The EU is committed to improving this situation, notably through the EU Rural Action Plan, which supports the uptake of female entrepreneurship and the provision of adequate services in rural areas (for example, those designed to stimulate female employment rates).

This article focuses on gender-based statistics for people living in rural areas: it forms part of Eurostat’s online publication Rural Europe.

Full article

Demography

Rural areas of the EU are sometimes characterised by gender-selective migration. The number of relatively young women leaving rural areas tends to exceed that for relatively young men. This may be linked, among other factors, to the range of employment opportunities available in rural areas, family farms being predominantly passed down to male heirs, or to a higher proportion of young women leaving rural areas to continue their education. These patterns can result in demographic imbalances both between and within regions, and may hamper the socioeconomic development of some rural areas.

Figure 1 shows that females of working age (defined here as 20–64 years) accounted for somewhat more than half (55.8 %) of the female population living in predominantly rural regions of the EU on 1 January 2021. Older women (aged 65 years or over) accounted for almost a quarter (24.9 %) of the female population in predominantly rural regions, with a 19.3 % share for girls and young women (aged less than 20 years).

A comparison between the sexes reveals that a considerably higher share of the male population living in predominantly rural regions of the EU were of working age (59.3 %; some 3.5 percentage points higher than the corresponding figure for females), while older men accounted for a smaller share of the male population, in part, reflecting the fact that women tend to live longer.

(% share of rural population)

Source: Eurostat (urt_pjangrp3)

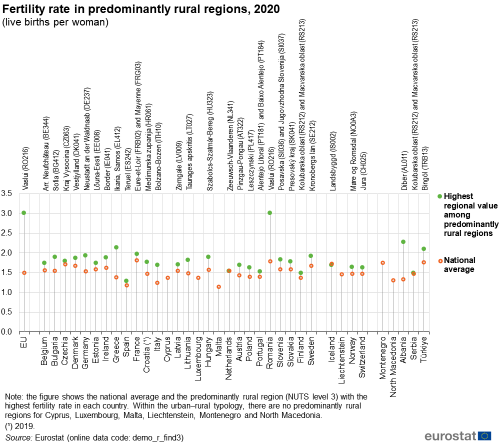

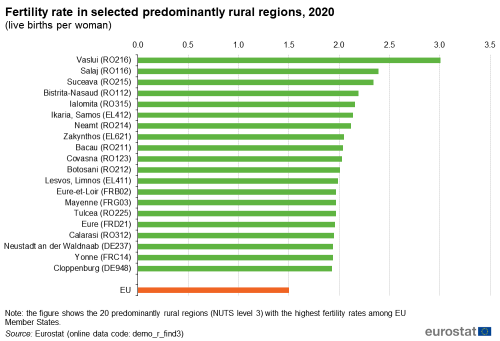

In 2020, the EU fertility rate stood at 1.50 live births per woman. The range of fertility rates across predominantly rural regions of the EU was from 0.70 in El Hierro (Canarias, Spain) to 3.01 in Vaslui (eastern Romania).

- Apart from the Netherlands, all of the EU Member States reported that at least one of their predominantly rural regions had a fertility rate that was higher than the national average (note that within the urban–rural typology, there are no predominantly rural regions for Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta).

- The highest fertility rates among predominantly rural regions of the EU Member States ranged from 1.29 live births per woman in Teruel (eastern Spain) up to 3.01 in Vaslui (Romania).

- The biggest differences between fertility rates in a predominantly rural region and national averages were recorded in the Greek island region of Ikaria, Samos (where the fertility rate was 0.76 live births per woman higher than the national average) and in the Romanian region of Vaslui (1.22 live births per woman higher).

Figure 3 shows the 20 predominantly rural regions of the EU that had the highest fertility rates in 2020. Seven of these regions had a fertility rate equal to or above 2.10: this value is considered the natural replacement rate in developed economies (a level of fertility at which the population replaces itself from one generation to the next, if mortality rates remain constant and there is no impact from net migration). As noted above, the highest fertility rate among predominantly rural regions was in the eastern Romanian region of Vaslui (3.01 live births per woman in 2020). Five more predominantly rural regions in Romania also recorded fertility rates higher than 2.10; this was also the case in the Greek island region of Ikaria, Samos.

(live births per woman)

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_find3)

(live births per woman)

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_find3)

Gender differences in education

Education can play an important role in determining life chances and raising the quality of life of an individual. It also has social returns, insofar as raising overall educational standards will likely result in a more productive workforce which, in turn, may drive economic growth. In a similar manner, a lack of educational skills and qualifications is likely to restrict access to a variety of jobs/careers.

A Council Resolution on a strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training towards the European Education Area and beyond (2021/C 66/01) outlines seven EU-wide policy targets for the period 2021–2030. One of these concerns the share of early leavers from education and training, where an EU target of less than 9 % has been set for 2030.

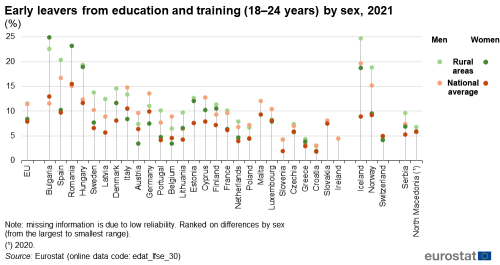

In 2021, almost one tenth (9.7 %) of young people aged 18–24 years in the EU were early leavers from education and training. An analysis based on the degree of urbanisation reveals that this ratio was slightly higher, at 10.0 %, for young people living in rural areas. There were considerable differences between the EU Member States when this share is analysed by sex (see Figure 4):

- particularly high rates of early leavers were recorded in the rural areas of Spain (for young men), Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria;

- by contrast, the share of early leavers from education and training was lower than the national average – for both women and men – across the rural areas of Belgium, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and Austria;

- within rural areas, Bulgaria was the only Member State to report a higher share of early leavers among young women.

A more detailed analysis of the gender gap for early leavers from education and training in rural areas is presented in Figure 5. In rural areas of the EU, the share of female early leavers from education and training fell from 11.9 % to 8.4 % between 2012 and 2021, while the share of male early leavers fell from 16.0 % to 11.5 %. With a faster reduction in male rates, the EU gender gap narrowed from 4.1 percentage points in 2012 to 3.1 points in 2021; note that due to a break in series, data for 2021 are not fully comparable with the previous years. This pattern – a narrowing of the gender gap over time – was repeated in a majority of the EU Member States: 14 of the 19 Member States where the share was higher for men as well as the exceptional case of Bulgaria where the share was higher for women.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_30)

(percentage points)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_30)

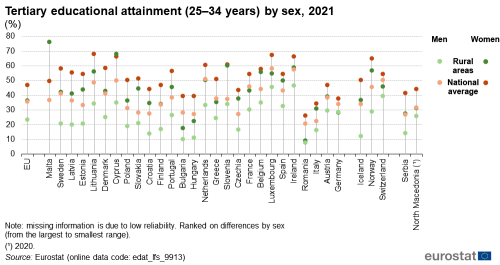

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9913)

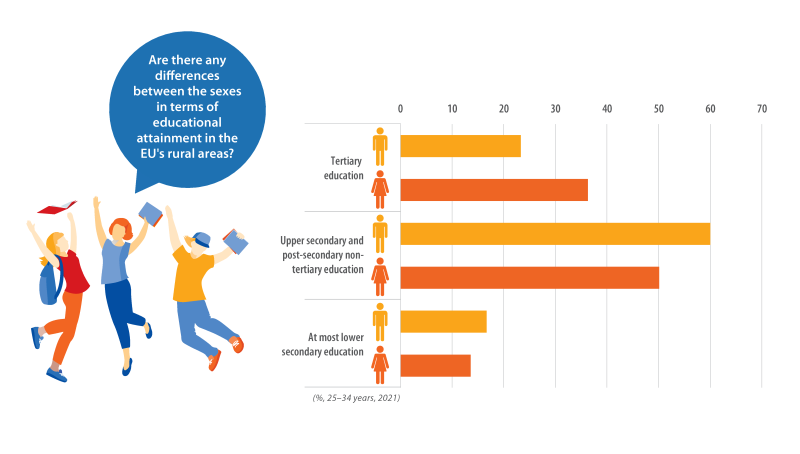

In 2021, around one sixth (16.7 %) of young men (aged 25–34 years) living in rural areas of the EU had, at most, a lower secondary level of educational attainment (as defined by ISCED levels 0–2), which was 3.1 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for young women (13.6 %). This gender gap in educational attainment levels was repeated in a majority of EU Member States (incomplete or no data for Ireland and Malta), with higher shares of young men having a relatively low level of educational attainment; in Estonia, Cyprus and Spain, the gap was more than 10.0 percentage points. By contrast, there were five (mainly eastern) Member States where a higher share of young women had at most a lower secondary level of educational attainment: this gap was relatively small in Hungary, Austria and Slovakia (no more than 2.5 percentage points), but was 3.7 points in Bulgaria and peaked at 7.5 points in Romania.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9913)

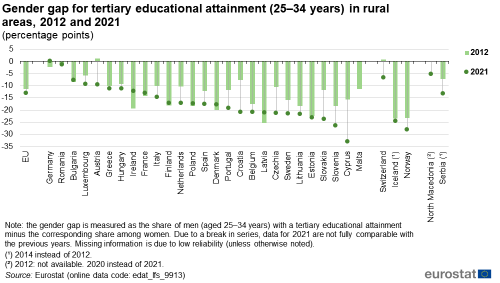

(percentage points)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9913)

Another target set within the strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training was to have at least 45 % of 25–34 year-olds with tertiary educational attainment by 2030. More than one third (36.3 %) of young women (aged 25–34 years) living in rural areas of the EU had a tertiary level of educational attainment (as defined by ISCED levels 5–8). The corresponding share for young men was less than one quarter (23.3 %); as such, there was a gender gap of 13.0 percentage points. This gap in tertiary educational attainment was observed in the vast majority of EU Member States (incomplete data for Malta). Germany was the only Member State to report a higher share of young men (rather than young women) living in rural areas with a tertiary level of educational attainment, although the gap between the sexes was very small (0.2 percentage points). Elsewhere, the gap in favour of young women ranged from 1.3 percentage points in Romania, and less than 10.0 points in Bulgaria, Luxembourg and Austria, up to 26.4 points in Slovenia and 33.0 points in Cyprus.

A more detailed analysis of the gender gap for tertiary educational attainment in rural areas is presented in Figure 8. In rural areas of the EU, the share of women (aged 25–34 years) with a tertiary education rose from 30.5 % to 36.3 % between 2012 and 2021; note again that due to a break in series, data for 2021 are not fully comparable with the previous years. During the same period, the share of young men living in rural areas with a tertiary education rose from 19.2 % to 23.3 %. With a faster increase in tertiary educational attainment among young women, the EU gender gap widened from 11.3 percentage points in 2012 to 13.0 points in 2021. This pattern – a widening of the gender gap over time – was repeated in 18 of the 26 EU Member States for which data are available (incomplete data for Malta) and was particularly pronounced in Czechia, Austria (where the gender gap was initially in favour of young men in 2012), Slovakia, Croatia and Cyprus. Among the eight Member States where the gender gap in tertiary educational attainment narrowed between 2012 and 2021, the gap fell at a relatively fast pace in Latvia and particularly Ireland, while in Germany it reversed from being in favour of young women in 2012.

Gender differences in the labour market

Despite a strong political commitment to promote gender equality across the EU, large differences between women and men still exist in various domains of life. Among these is the labour market, where issues concern, for example, access, equal pay and working conditions, or gender-balanced leadership in decision-making.

As shown in the previous section, almost all of the EU Member States reported that a higher share of women (than men) living in rural areas had a tertiary level of educational attainment. However, this has rarely translated into better labour market outcomes for women (both in terms of the quantity and quality of employment). This reflects – at least in part – the slow pace of change in social expectations which create barriers to participation. In 2021, just over two thirds (67.3 %) of all women of working age (20–64 years) living in rural areas of the EU were in employment. The employment rate for men living in rural areas was considerably higher, at 79.6 %, resulting in a gender gap of 12.3 percentage points. The gender gap in employment rates was wider for people living in rural areas than it was for the population as a whole (where there was a gap of 10.8 points), suggesting that women living in rural areas had more difficulty to find work or that the necessary conditions to encourage some women to move into or re-enter the workforce were missing.

Figure 9 shows how EU employment rates for men and women developed during the period 2012–2021. It is interesting to note that employment rates for rural areas tended to fluctuate more than the average development for the whole of the EU territory and that this was the case for both women and men.

In 2021, the EU employment rate for men (aged 20–64 years) living in rural areas was 79.6 %. This figure was 1.1 percentage points higher than the employment rate for men across the whole of the EU territory (78.5 %). By contrast, the employment rate for women living in rural areas was 67.3 %, which was slightly (0.4 points) lower than the average rate for women across the whole of the EU territory (64.7 %). This pattern – lower employment rates for women living in rural areas (compared with the national average for all women) – was repeated in 19 of the 27 EU Member States, including all of the eastern and Baltic Member States; it was most apparent in Bulgaria and Romania, where the latest rates for rural areas were 12.1 and 12.4 percentage points, respectively, lower than average. By contrast, female employment rates for rural areas were higher than average in Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands, France, Austria, Germany, Belgium and Malta.

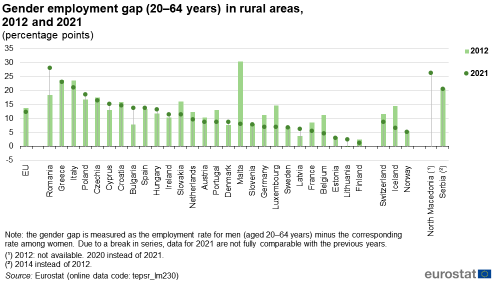

Figure 11 presents an analysis of the gender employment gap for working-age people (20–64 years) living in rural areas. In 2021, the employment rate for men living in rural areas of the EU was 79.6 %, which was 12.3 percentage points higher than the corresponding rate for women. This gender gap narrowed marginally during the last decade, as it had been 13.7 points in 2012; note again that due to a break in series, data for 2021 are not fully comparable with the previous years.

Within rural areas, male employment rates were persistently higher than female employment rates across all of the EU Member States in 2021; this was also the case in 2012, except for Lithuania (where the female employment rate had been marginally higher). There were 12 Member States where the gender employment gap for rural areas was in double-digits in 2021. This gap was more than 20.0 percentage points in Italy, Greece and Romania (where a peak of 28.2 points was observed). These gaps may be explained, at least in part, by the particularly low level of female employment rates; for example, less than half of all working-age women were employed in Greece and Romania.

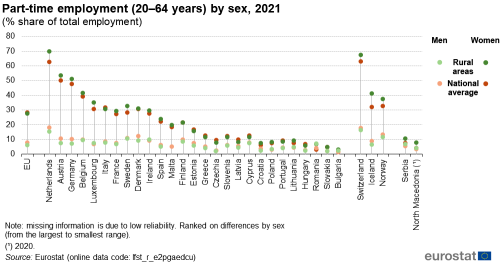

Policy measures that seek to promote, among other actions, childcare support, working from home, flexible working hours, part-time work or other forms of atypical employment – tend to enhance women’s participation within the labour force. Looking in more detail at part-time work, its prevalence within the EU has steadily increased during recent decades. This can be seen as a positive development if it reflects, on the part of employees, a genuine choice to improve their work-life balance, or if it increases employment opportunities among individuals previously excluded from the labour market. However, some part-time work is involuntary: for example, people who accept part-time work because there is a shortage/absence of full-time posts, or people who cannot reconcile their working lives with family responsibilities without reducing their working hours.

(percentage points)

Source: Eurostat (tepsr_lm230)

(% share of total employment)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_e2pgaedcu)

The share of employed people working on a part-time basis differs considerably across EU Member States. It is most common in the Netherlands, Austria, Germany or Belgium. The share of persons working on a part-time basis is generally much lower across several eastern and Baltic Member States (where young children are often cared for directly by family members).

Part-time employment remains a highly gendered phenomenon: in 2021, 28.3 % of women (aged 20–64 years) in the EU worked on a part-time basis, compared with a much lower share among men (7.6 %). These differences often result from women reducing their working hours after childbirth to balance work and care responsibilities. In rural areas, the share of women working on a part-time basis was higher than for men in all EU Member States (no data for Malta) other than in Romania. The share of women working on a part-time basis was higher in rural areas (than the national average) in 18 of the EU Member States, with the widest gaps observed in the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Sweden.

In 2021, some 13.0 % of employees (aged 20–64 years) in the EU were employed with a fixed-term contract; this figure was somewhat higher for women (13.8 %) than it was for men (12.2 %). A more detailed analysis by degree of urbanisation reveals that the share of male and female employees living in rural areas of the EU and employed with a fixed-term contract was somewhat lower than average.

Across the EU Member States, the share of female employees (aged 20–64 years) in rural areas working with a fixed-term contract was generally higher than the corresponding share for male employees; there was no difference between the sexes for this share in Slovakia, while higher shares were recorded for male employees living in rural areas of Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania. In 10 southern and eastern Member States as well as in Ireland, the share of employees in rural areas with a fixed-term contract was higher than the national average for men and also for women; these gaps were particularly apparent in Greece.

(% share of total employees)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_e2tgaedcu)

Unemployment can have a bearing not just on the macroeconomic performance of a country (lowering productive capacity) but also on the well-being of individuals without work and their families. The personal and social costs of unemployment are varied and include a higher risk of poverty and social exclusion, debt or homelessness, while the stigma of being unemployed may have a potentially detrimental impact on (mental) health.

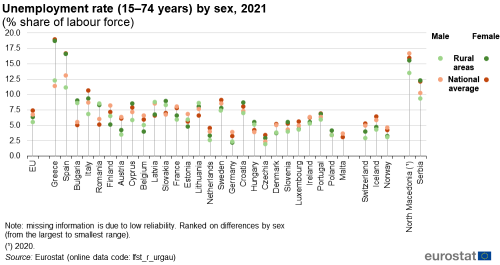

In 2021, the EU’s unemployment rate (for people aged 15–74 years) was 7.0 %: an analysis by degree of urbanisation reveals that the unemployment rate was considerably lower in rural areas (5.9 %). During the most recent 10-year period for which data are available (2012–2021), the female unemployment rate in rural areas fell at a more rapid pace (than the overall female unemployment rate for the whole of the EU territory); note again that due to a break in series, data for 2021 are not fully comparable with the previous years. By contrast, the gap between the male unemployment rates for rural areas and the male unemployment rate for the whole of the EU territory remained relatively stable during the period under consideration.

(% share of labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_urgau)

(% share of labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_urgau)

Among the EU Member States, it was more often the case that unemployment rates for rural areas were lower than national rates observed for the whole territory. In 2021, this pattern was repeated in more than half of the Member States (15 out of 26; no data for Malta), both for male and female unemployment rates, whereas:

- in Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia, unemployment rates in rural areas for both males and females were at least as high as average;

- in Croatia, Cyprus and Slovenia, female unemployment rates for rural areas were higher than average (while male rates were lower than average);

- in Greece, male unemployment rates for rural areas were higher than average (while female rates were lower than average).

The EU’s gender unemployment gap (for people aged 15–74 years) for rural areas remained relatively stable during the period from 2012 to 2021. The female unemployment rate had been 0.9 percentage points higher (than the male rate) in 2012, with this gap rising to 1.1 points the following year. The gender unemployment gap thereafter narrowed to 0.7 points in 2020, before increasing marginally a year later to stand at 0.8 points in 2021; see Figure 16.

The unemployment rate for females living in rural areas was generally higher than the rate for males. In 2021, this pattern was observed in 18 out of 26 EU Member States (no data for Malta), with the largest gender gaps observed in Greece (where the female unemployment rate for rural areas was 6.4 percentage points higher than the male rate) and Spain (where the female rate was 5.5 points higher). In the eight Member States where male unemployment rates for rural areas were higher than female rates, differences between the sexes were relatively narrow. The largest gender gap for this group was recorded in Latvia (where the male unemployment rate for rural areas was 2.1 percentage points higher than the female rate).

(percentage points)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_urgau)

Youth unemployment is a major societal issue. In October 2020, a Council Recommendation on A Bridge to Jobs (2020/C 372/01) called on EU Member States to ensure that all young people under 30 years of age receive a good quality offer of employment, continued education, an apprenticeship or a traineeship within a period of four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education – the reinforced Youth Guarantee. This recommendation provides comprehensive support across the EU, adopting a more tailored approach by providing young people, in particular vulnerable ones, with guidance especially suited to their individual needs, the green and digital transitions of the EU economy, and the challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2021, the EU’s youth unemployment rate (defined here for persons aged 15–24 years) was 16.6 %. It is important to note that the youth unemployment rate is calculated on the same basis as the overall unemployment rate, with its denominator being the number of young people in the labour force (in other words, the sum of employed and unemployed persons aged 15–24 years). As such, a youth unemployment rate of 16.6 % does not mean that one sixth of all youths were unemployed; rather, it signifies that one sixth of all young people aged 15–24 years within the labour force were without work. A considerable number of young people may remain outside the labour force (for example, in full-time education or training); these young people are not taken into consideration when calculating youth unemployment rates.

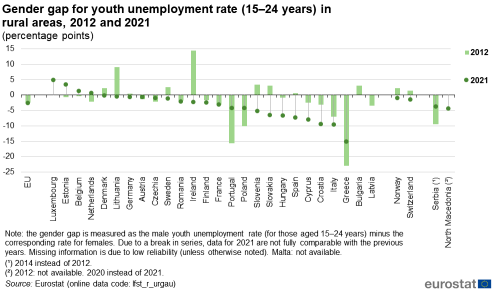

Figure 17 shows that there was little difference in youth unemployment rates if comparing young females living in the EU’s rural areas with those living across the whole of the EU territory. By contrast, there was a more pronounced difference for young men: the youth unemployment rate for males in rural areas was 13.5 %, some 3.0 percentage points lower than the average for all young males in the EU economy (16.5 %). This difference may be attributed to a concentration of male youth unemployment in cities (a pattern that was particularly apparent in Spain, Italy and several western EU Member States).

Youth unemployment rates in rural areas were generally lower for males than they were for females in 2021. The gender gap for youth unemployment across rural areas of the EU was 2.6 percentage points.

- There were four EU Member States where the female youth unemployment rate in rural areas was lower than the corresponding male rate – this group included all three Benelux Member States as well as Estonia.

- The biggest gender gaps – with lower youth unemployment rates for males – were observed around the Mediterranean in Spain, Cyprus, Croatia, Italy and Greece; in the latter, the female youth unemployment rate for rural areas was 15.1 percentage points higher than the corresponding male rate.

(% share of labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_urgau)

(percentage points)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_urgau)

Gender differences in living conditions

The number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion is a headline indicator for social protection and inclusion within the European pillar of social rights. This indicator forms the basis for one of three social targets to be achieved by 2030, namely, that the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion should be reduced by at least 15 million (of which, at least five million should be children) when compared with 2019.

People at risk of poverty or social exclusion

To calculate the number or share of people who are at risk of poverty or social exclusion three separate criteria are combined, covering people who are in at least one of the following situations.

- At risk of poverty – people with an equivalised disposable income (after social transfers) below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income after social transfers.

- Facing severe material and social deprivation – people unable to afford at least 7 out of 13 selected items (six of which are related to the individual and seven of which are related to the household in which they live) that are considered by most to be desirable (or even necessary) for having an adequate quality of life.

- Living in a household with very low work intensity – where working-age adults (aged 18–64 years, excluding students aged 18–24 years and those who are retired) worked no more than 20 % of their total potential during the previous 12 months.

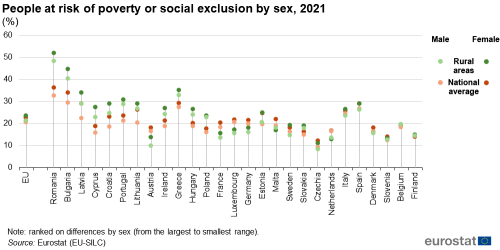

Across the EU, there were 95.4 million persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2021; this was equivalent to more than one fifth (21.7 %) of the population. The risk of poverty or social exclusion was somewhat higher among women (22.6 %) than it was among men (20.7 %). An analysis by degree of urbanisation reveals that people living in rural areas faced a greater risk of poverty or social exclusion (than the average for people in the EU), with shares 1.0 percentage points higher for females and 0.6 points higher for males.

In 2021, the risk of poverty or social exclusion in rural areas of the EU was 23.6 % for females, some 2.3 percentage points higher than for males (21.3 %). This gender gap was slightly wider in 2021 than it had been six years earlier (2.0 points in 2015). In the vast majority of EU Member States, females living in rural areas faced a higher risk of poverty or social exclusion than males:

- there were three exceptions – with a higher risk observed among males living in the rural areas of Belgium, the Netherlands and Malta;

- the biggest gender gaps – where the risk of poverty or social exclusion for females living in rural areas was more than 4.0 percentage points higher than for males – were recorded in Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Sweden and Latvia.

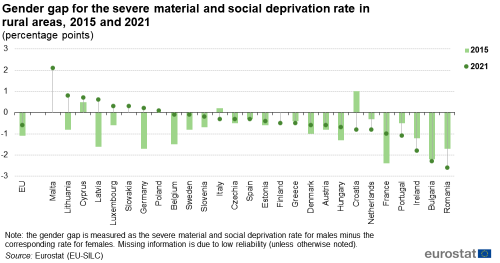

There were 27.1 million people across the EU facing severe material and social deprivation in 2021; this was equivalent to 6.3 % of the total population. Figure 21 shows that in the EU Member States where the risk of severe material and social deprivation was relatively high it was common to observe higher rates for people living in rural areas, in particular for females.

In 2021, the severe material and social deprivation rate for females living in rural areas of the EU was 7.2 %; this was 0.6 percentage points higher than the share recorded for males. A gender gap with higher shares for females was repeated in 19 of the EU Member States, with the largest gaps observed in Bulgaria and Romania. By contrast, in Poland, Germany, Luxembourg, Slovakia, Latvia, Cyprus, Lithuania and Malta, a higher proportion of males (than females) living in rural areas faced severe material and social deprivation.

EU median equivalised net income was €18 400 in 2021; on average, males (€18 800) had a higher level of income than females (€18 000). Figure 25 shows developments for the period 2012–2021.

- The impact of the global financial and economic crisis led to income falling in rural areas through to 2013, while by then there was already a modest increase in income across the whole economy.

- The growth of income across the whole economy stalled in 2021 (perhaps reflecting the impact of the COVID-19 crisis and the beginning of the cost-of-living crisis), while income levels in rural areas continued to rise by a similar rate to previous years.

- Median equivalised net income levels for females were consistently lower than the income levels observed for males, both across the whole economy and in rural areas.

Figure 24 also shows information for median equivalised net incomes; note that the value are denominated in terms of purchasing power standards (PPS); a PPS is a unit that takes account of price-level differences between countries. The median equivalised net income of males in the EU was 4.1 % higher than for females in 2021; this gender gap was somewhat narrower in rural areas (where the net income of males was 3.9 % higher than that of females).

The average level of income for males living in rural areas was, with the exception of Malta, consistently higher than the average observed for females. The largest relative differences in income levels among those living in rural areas – with the median equivalised net income of males at least 7.5 % higher than for females – were recorded in Sweden, Bulgaria, Italy and Latvia. In a majority of the EU Member States, the gender gap for median equivalised net income was greater in rural areas than it was, on average, across the whole economy; this gap was particularly notable in Italy and Sweden.

(€)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_di17) and (ilc_di03)

(difference between male and female incomes as % of male incomes, based on PPS series)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_di17) and (ilc_di03)

Source data for tables and graphs

Context

Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, has stated that ‘Gender equality is a core principle of the European Union, but it is not yet a reality. In business, politics and society as a whole, we can only reach our full potential if we use all of our talent and diversity. Using only half of the population, half of the ideas or half of the energy is not good enough.’

The European Commission’s Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025 sets out a range of policy objectives and key actions, designed to help the EU achieve the fifth Sustainable Development Goal, namely, to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. The key actions include, among others, closing gender gaps in the labour market, achieving equal participation across different sectors of the economy, addressing the gender pay and pension gaps, and attaining gender balance in decision-making and politics. The implementation of the strategy is based on the dual approach of targeted measures for gender equality combined with enhanced gender mainstreaming in all policy areas.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) supports gender equality in rural areas through its strategic plans (for the period 2023–2027), in particular under Specific objective 8: Jobs, growth and equality in rural areas). This objective promotes employment, growth, gender equality (including the participation of women in farming), social inclusion and local development in rural areas, as well as the circular bio-economy and sustainable forestry.

Direct access to

Online publications

- Ageing Europe – looking at the lives of older people in the EU

- EU labour force survey statistics

- Eurostat regional yearbook

- Living conditions in Europe

- Quality of life indicators

- Rural Europe

- Urban Europe

Methodological publications

- Applying the Degree of Urbanisation – 2021 edition

- EU labour force survey

- Methodological manual on territorial typologies – 2018 edition

Background articles

Statistical publications

- Eurostat regional yearbook – 2022 edition

- Living conditions in Europe – 2018 edition

- Report on the impact of demographic change – 2020 edition

- Urban Europe – statistics on cities, towns and suburbs – 2016 edition

Methodological publications

- Applying the degree of urbanisation – A methodological manual to define cities, towns and rural areas for international comparisons – 2021 edition

- Education and training – methodology

- EU labour force survey – methodology

- EU labour force survey – new methodology from 2021 onwards

- Income and living conditions – methodology]

- EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) methodology

- Methodological manual on territorial typologies – 2018 edition

- Statistical regions in the European Union and partner countries: NUTS and statistical regions 2021 – 2022 edition

Statistical legislation

- Education and training – legislation

- Employment and unemployment (LFS) – legislation

- Income and living conditions – legislation

- Regulation (EU) 2017/2391 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2017 amending Regulation (EC) No 1059/2003 as regards the territorial typologies (Tercet)

- Consolidated and amended version of Regulation (EC) No 1059/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the establishment of a common classification of territorial units for statistics (NUTS)

Policy legislation

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 522/2014 of 11 March 2014 supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1301/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to the detailed rules concerning the principles for the selection and management of innovative actions in the area of sustainable urban development to be supported by the European Regional Development Fund

- Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD)

- Regulation (EU) No 1310/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 laying down certain transitional provisions on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD)

Visualisations

European Commission – Directorate-General Agriculture and rural development

European Commission – Directorate-General Regional and Urban Policy

- Cities and urban development

- Cohesion in Europe towards 2050; eighth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion

- Territorial cohesion

- Urban–rural linkages

European Committee of the Regions

European networks

United Nations