Regional socioeconomic developments - statistics

Data extracted in March and April 2019.

Planned article update: None.

Highlights

Between 2008 and 2016, the highest increases in regional household disposable income per inhabitant were in London, Denmark and Sweden (at least EUR 4 500 per inhabitant).

Between 2008 and 2017, a majority of the 52 EU regions recording a real contraction in value added were found in Greece, Spain and Italy.

In 2017, the United Kingdom (Inner London – West) recorded the highest regional household disposable income per inhabitant (EUR 55 200), and Bulgaria (Severozapaden) the lowest (EUR 2 900).

The European Union (EU’s) regional policy aims to support the broader Europe 2020 agenda. It is designed to foster solidarity, such that each region may achieve its full potential by alleviating economic, social and territorial disparities. During the period 2014-2020, almost one third of the EU’s total budget is devoted to cohesion policy.

At the time of writing, just over a decade has passed since the global financial and economic crisis started. The analysis in this chapter aims to give an idea — based on a small selection of indicators — how resilient or vulnerable the regions in the EU were. The main focus of the analyses is the combined impact of the crisis and the subsequent recovery, to see how well the regions bounced back: have some leapt ahead while others have not yet returned to their pre-crisis levels?

This chapter uses key indicators from a variety of datasets to analyse socioeconomic developments within the EU-28 from 2008 — when the global financial and economic crisis was first felt in the EU — through until the most recent period, namely 2016, 2017 or 2018 (depending on the indicator concerned).

The first section is based on regional gross domestic product (GDP), the principal aggregate for measuring the economic output of an economy. It is followed by a regional analysis of gross value added, which is the main component of GDP (when compiled from the output approach). Two more national accounts indicators follow: household disposable income per inhabitant and labour productivity. The next section starts with information on population developments before moving on to an indicator of tertiary educational attainment among adults. This is followed by a measure of the working-age population, while the chapter concludes with two analyses concerning the employment rate.

Full article

Regional GDP per inhabitant

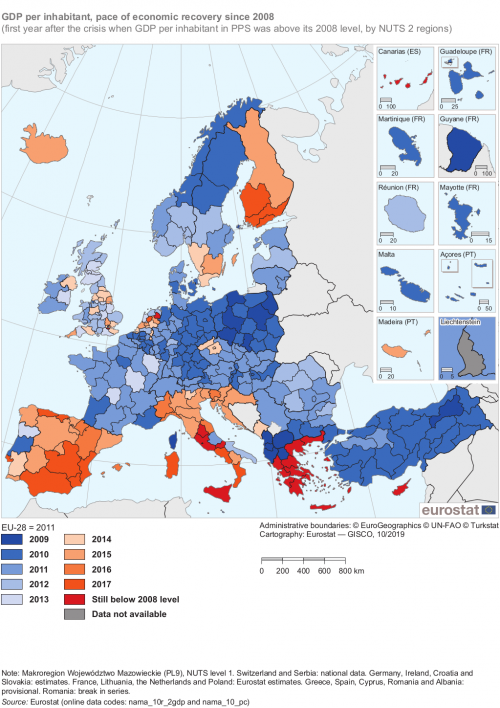

The first analysis — see Map 1 — focuses on GDP per inhabitant. In order to compensate for price level differences across countries, the GDP data presented here have been converted using conversion factors known as purchasing power parities (PPPs). The use of PPPs (rather than market exchange rates) results in the data being converted into an artificial common currency called a purchasing power standard (PPS).

The idea behind the analysis in Map 1 is that, having peaked in 2008, the value of this indicator fell in 2009 (and possibly also one or more subsequent years) as a result of the crisis and then subsequently rose as regional economies recovered. The map shows in which year (therefore how quickly) each region had recovered to the extent that its GDP per inhabitant had surpassed its 2008 level. However, 10 of the 280 NUTS level 2 regions were exceptions in that their GDP per inhabitant actually rose rather than fell in 2009: six of these regions were in Poland, two in France and one each in Greece and Finland. Most of them experienced an uninterrupted increase in their GDP per inhabitant despite the crisis, as was the case in Corsica (France) and the six Polish regions. The other three regions — Dytiki Makedonia (Greece), Guyane (France) and Åland (Finland) — recorded a fall one year later, in other words their GDP per inhabitant peaked in 2009 rather than in 2008.

(first year after the crisis when GDP per inhabitant in PPS was above its 2008 level, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10r_2gdp) and (nama_10_pc)

Leaving these 10 exceptions aside, GDP per inhabitant in approximately half of the remaining 270 regions had moved back above its 2008 level within two years, 66 regions achieving this in 2010 (in other words, after just one year below the 2008 level) and 70 in 2011. A total of 111 of the remaining 134 regions had spent between three and eight years with their GDP per inhabitant below its 2008 level: 28 had recovered by 2012, 16 by 2013, 20 by 2014, 27 by 2015, 7 by 2016 and 14 by 2017.

The remaining 22 regions recorded nine consecutive years — from 2009 up to the most recent year (2017) — with GDP per inhabitant below its 2008 level. These included:

- all of the remaining 12 Greek regions (other the Dytiki Makedonia mentioned above);

- three Spanish regions (Canarias and the Ciudades Autónomas de Ceuta y Melilla);

- four central, southern and island regions of Italy.

Looking more generally at Map 1 it can be seen that GDP per inhabitant in most regions in the north, west and east of the EU had stayed above or returned above their 2008 level by 2013 at the latest, with the exceptions of:

- much of Finland and several regions in Sweden among the northern EU Member States;

- several regions in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom among the western Member States;

- Croatia, Slovenia and a few regions of Czechia among the eastern Member States.

The main concentration of regions whose GDP per inhabitant was still below its 2008 level by 2014 was in the southern EU Member States of Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus and Portugal. Along with Malta (one region at this level of detail), the only other regions in the southern Member States where GDP per inhabitant had in fact returned above its 2008 level before 2014 included:

- four Italian regions — Valle d’Aosta/Vallée d’Aoste, Abruzzo, Puglia and the Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano/Bozen;

- three Portuguese regions — Norte, Centro and the Região Autónoma dos Açores.

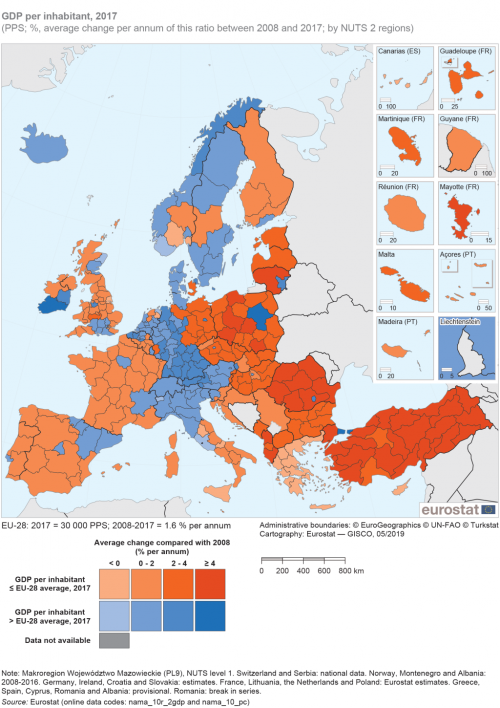

GDP per inhabitant in Inner London — West was more than 6.3 times as high as the EU-28 average

The information presented in Map 2 is based on the same indicator, namely GDP per inhabitant in PPS. This map shows the level of GDP per inhabitant for the most recent year, 2017, as well as its annual average change between 2008 and 2017. As such, the rate of change covers a relatively long period of time including the crisis and the subsequent recovery, insofar as nearly all regions have recovered at least to the level they were at in 2008. Note a previous chapter on economy at regional level provides a detailed analysis of the latest data for GDP per inhabitant and so the analysis here starts with just a few key points concerning 2017 before concentrating on the change between 2008 and 2017.

Regions which may be considered as relatively ‘rich’ — with GDP per inhabitant above the EU-28 average in 2017 — are shown in blue, while those that may be considered as relatively ‘poor’ are shown in orange. The lightest shade of orange and of blue indicate regions whose GDP per inhabitant in 2017 was (still or again) below its 2008 level, in other words with a negative rate of change between these years in relation to the EU-28. The other three shades of orange and of blue show regions that experienced a more positive development than the EU-28 during the period under consideration, with darker shades for regions with stronger growth.

Economic activity across the EU in 2017 was somewhat skewed insofar as 105 out of the 280 regions for which data are available recorded a level of GDP per inhabitant above the EU-28 average; as such, wealth creation was concentrated in regional pockets, while a higher share of regions experienced below average levels of GDP per inhabitant. The relatively rich regions were largely found in a band that ran from northern Italy, up through Austria and Germany before splitting in one direction towards several regions in the Benelux countries, southern England, Eastern and North-Eastern Scotland, and Southern Ireland, and in the other direction towards the Nordic EU Member States. Other regions with GDP per inhabitant above the EU-28 average were often capital city regions (for example in Bulgaria, Czechia, Spain, France, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia) as well as in north-east Spain and Rhône-Alpes in France.

The highest GDP per inhabitant was in one of the two capital city regions of the United Kingdom, Inner London — West, where GDP per inhabitant was more than six times as high as the EU-28 average in 2017. Luxembourg (one region at this level of detail), Southern Ireland and Hamburg (Germany) were the only other regions across the EU where GDP per inhabitant was at least twice as high as the EU-28 average.

While the highest levels of GDP per inhabitant were generally recorded in capital city regions of EU Member States, the contrast between the economic performance of capital city regions and their surrounding regions was in some ways particularly stark in several eastern Member States, notably in Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia.

The list of regions where GDP per inhabitant was lower in 2017 than in 2008 was largely comprised of regions with low levels of GDP per inhabitant

There were 27 regions that had lower GDP per inhabitant in 2017 than in 2008. These included the 22 regions identified in Map 1 as having not yet (by 2017) recovered their 2008 level of GDP per inhabitant, as well as:

- Dytiki Makedonia in Greece (whose GDP per inhabitant did not start to fall until 2010);

- Valle d’Aosta/Vallée d’Aoste in Italy;

- Groningen in the Netherlands;

- East Yorkshire and Northern Lincolnshire, and North Eastern Scotland, both in the United Kingdom.

GDP per inhabitant had recovered above its 2008 level in each of these five additional regions, but had subsequently fallen back below it again. Among the 27 regions with lower GDP per inhabitant in 2017 than in 2008, 85 % of them had a level of GDP per inhabitant in 2017 that was below the EU-28 average, the exceptions being Valle d’Aosta/Vallée d’Aoste, Groningen, North Eastern Scotland and Lazio.

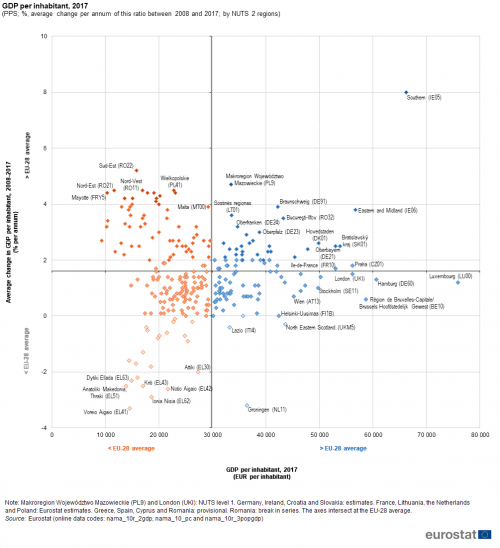

The most rapid growth in wealth generation during the period 2008-2017 was among regions that had relatively low GDP per inhabitant, mainly in Poland and Romania

As such, 253 regions recorded a higher level of GDP per inhabitant in 2017 than in 2008. Of these, 161 different regions recorded annual average growth of less than 2.0 % per year. A total of 76 regions recorded annual average growth of at least 2.0 % per year but less than 4.0 % per year. The remaining 16 regions recorded annual average growth of at least 4.0 % per year. The proportion of regions with GDP per inhabitant below the EU-28 average in 2017 was particularly high among those with the strongest average growth, as was the case among those with a negative rate of change (below 0 %).

Among the 16 regions with the highest rate of increase in GDP per inhabitant between 2008 and 2017 were two with above average GDP per inhabitant in 2017, namely Southern Ireland and the Polish capital city region (Makroregion Województwo Mazowieckie; a NUTS level 1 region). The other 14 regions — all with below average GDP per inhabitant — included:

- five more Polish regions (Małopolskie, Wielkopolskie, Dolnośląskie, Pomorskie and Łódzkie);

- seven Romanian regions (Nord-Vest, Centru, Nord-Est, Sud-Est, Sud-Muntenia, Sud-Vest Oltenia and Vest).

As such, Poland was the only EU Member State whose capital city region recorded annual average growth of 4.0 % or more. Most of the 16 regions with the highest annual average growth recorded growth in the range of 4.0-4.7 %, with the Sud-Est region of Romania (5.2 %) and Southern Ireland (8.0 %) above this.

A comparison of EU Member States composed of more than one NUTS level 2 region reveals GDP per inhabitant grew at an equal or faster pace than the EU-28 average in every region of Bulgaria, Denmark, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia, as well as every region except one in Czechia (Severozápad), Ireland (Northern and Western), Hungary (Pest) and Austria (the capital city region, Wien). The vast majority of regions in Germany also recorded an increase in their relative living standards. There was also higher than average growth in Estonia, Latvia and Malta (each covered by a single region at this level of detail).

(PPS; %, average change per annum of this ratio between 2008 and 2017; by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10r_2gdp) and (nama_10_pc)

The east-west divide in terms of wealth creation in the EU-28 has become less pronounced

Although there remains an east-west divide in terms of wealth creation in the EU-28, this has become less pronounced. Among the 54 regions in eastern EU Member States that are shown in Map 2, six (all of which were capital city regions) had average GDP per inhabitant that was above the EU-28 average in 2017 and 48 were below average. Only six of these 54 regions recorded slower growth in GDP per inhabitant between 2008 and 2017 than recorded for the EU-28 as a whole:

- Severozápad in Czechia;

- Pest in Hungary;

- both Croatian and both Slovenian regions.

All regions in southern EU Member States had below average growth in GDP per inhabitant, except for Malta and the Portuguese region of Norte

Among the 62 regions in southern EU Member States, 17 had average GDP per inhabitant that was above the EU-28 average in 2017 and 45 had a below average ratio. Only two of these 62 regions — Malta and the Portuguese region of Norte — recorded faster growth in GDP per inhabitant between 2008 and 2017 than recorded for the EU-28 as a whole.

The situation for western regions was much more varied. Among these, there were 54 regions, with lower that average GDP per inhabitant in 2017 and slower than average growth (or even a contraction) between 2008 and 2017, including:

- four regions within the Région Wallonne of Belgium;

- 20 regions across France;

- 26 regions across the United Kingdom.

By contrast, there were 21 regions in western EU Member States where GDP per inhabitant in 2017 below the EU-28 average was combined with growth between 2008 and 2017 that was equal to or higher than the EU-28 average, including:

- nine regions in Germany, mainly in the eastern part of the country;

- five French regions, comprising four overseas regions as well as Midi-Pyrénées;

- four regions in the United Kingdom (Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire; West Midlands; East Wales; Southern Scotland).

Although there is some evidence, at a national level, of economic convergence across the EU now that the EU Member States most affected by the global financial and economic crisis have started to show persistent signs of recovery, there remain contrasting patterns of regional development. During the past decade, some of the most rapid economic growth has been recorded in capital city regions; their expansion has often, at a national level, hidden much slower growth in other regions. Regional divergences since the crisis have largely been driven by the continued move towards services-based economies: highly productive sectors are concentrated in capital city or other metropolitan regions, and these tend to attract and retain the most highly-skilled employees. By contrast, former industrial heartlands and rural regions have, to some degree, been ‘left-behind’.

(PPS; %, average change per annum of this ratio between 2008 and 2017; by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10r_2gdp), (nama_10_pc) and (nama_10r_3popgdp)

Real rate of change for gross value added

Gross value added at basic prices is defined as output at basic prices minus intermediate consumption at purchaser prices. The sum of gross value added at basic prices over all activities plus taxes on products minus subsidies on products should equal GDP.

The information presented in Figure 2 looks at developments for total gross value added in real terms. In other words, the monetary value has been deflated to take account of price changes. Across the whole of the EU-28 the average real rate of change for total value added between 2008 and 2017 was an increase of 0.8 % per year (equivalent to an overall increase of 7.7 % for the period under consideration).

The majority of the 52 regions in the EU where a real contraction in value added was recorded in the decade from 2008 were in Greece, Spain and Italy

The majority of the 52 regions in the EU where a contraction in value added in real terms was recorded between 2008 and 2017 (time series for some regions start a year later and others finish a year earlier) were in Greece (all 13 regions), Spain (nine regions) and Italy (17 regions), while there were also multiple regions in each of Finland, Portugal and Romania.

The five regions in the EU to report the strongest contractions in value added in real terms were located in Greece and Romania. Value added in the Nord-Est region of Romania declined by 29.5 % between 2008 and 2016 (an average of 4.3 % per year), more than in any other region. The contraction in GDP in most of these five regions was mainly concentrated in the period from 2008 to 2011 or 2012, since when the real development of value added was relatively stable. The one exception was the Greek region of Dytiki Makedonia whose value added increased in 2009 before subsequently declining each and every year through until 2016.

The Irish region of Southern had the strongest growth, its value added increasing by 61.8 % overall between 2008 and 2017

The five regions in the EU to report the strongest growth in value added in real terms also included two Romanian regions, alongside two Irish regions and the Lithuanian capital city region. The Irish region of Southern had the strongest growth, value added increasing by 61.8 % overall between 2008 and 2017 (an average of 5.5 % per year). Interestingly it was not until 2014 that value added in the Irish region of Southern returned above its 2008 level; its leading position was achieved through exceptionally strong growth in 2015 assisted by further strong growth in 2016 and 2017.

(2008 = 100, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10r_2gvagr)

Private household income

Many of the ‘richest’ regions in the EU have a relatively high share of their wealth generated by inflowing commuters; this pattern is particularly true in capital city regions, where the cost of living in central locations often results in people living in suburban areas that may be in neighbouring NUTS regions. Commuter flows between regions (or across borders) lead employees to contribute to the wealth created in one region (where they work), while their household income is classified to another region (where they live). The high levels of value added (or GDP) per inhabitant that are recorded in some metropolitan regions characterised by large numbers of net incoming commuters overstate the true economic well-being in these regions. By contrast, the economic well-being of regions that surround capital city or metropolitan regions is likely to be understated when based on an analysis of average value added (or GDP) per inhabitant.

An alternative analysis is presented in Map 3, which provides information for household disposable income per inhabitant in NUTS level 2 regions; data are presented in euro and so are influenced by price differences between countries. Household disposable income is the total amount of money households have available for spending and saving after subtracting income taxes and pension contributions. Regions with household disposable income per inhabitant above the EU-28 average in 2016 are shown in blue in Map 3, while those with below average income are shown in orange. The lightest shade of orange and of blue indicate regions whose household disposable income per inhabitant in 2016 was below its 2008 level, in other words with a negative rate of change between these years. The other three shades of orange and of blue show regions with growth, with darker shades indicating those regions with stronger growth.

The highest regional household disposable income in the EU was EUR 55 200 per inhabitant in Inner London — West and the lowest EUR 2 900 per inhabitant in Severozapaden

In 2016, household disposable income in the EU-28 averaged EUR 15 600 per inhabitant. It ranged from a high of EUR 55 200 per inhabitant in Inner London — West (the United Kingdom) down to EUR 2 900 per inhabitant in Severozapaden (Bulgaria), a factor of 19.0 to 1. As such, the highest and lowest ratios were recorded for the same regions as GDP per inhabitant, where the difference between the two regions was 20.2 to 1 in 2017.

(EUR per inhabitant; overall change of this ratio between 2008 and 2016; by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10r_2hhinc), (nasa_10_nf_tr) and (nama_10_pe)

In 2016, 138 out of the 225 regions in the EU for which data are available recorded a level of household disposable income per inhabitant above the EU-28 average; as such, above average income was recorded in a majority of regions whereas the reverse was true for GDP per inhabitant. However, it should be noted that only national data are available for Ireland, France, the Netherlands and Poland and so they are each only counted once, despite the fact that collectively they have 59 NUTS level 2 regions. Bearing this in mind, it appears that the regional distribution of household disposable income per inhabitant was somewhat less skewed than that of GDP per inhabitant.

High household disposable income per inhabitant was mainly concentrated in western and Nordic EU Member States, but was also recorded in some Spanish and Italian regions

As for GDP per inhabitant, the regions with relatively high household disposable income per inhabitant were largely found in a band that ran from central and northern Italy, up through Austria and Germany before splitting in one direction towards the Benelux countries, the United Kingdom and Ireland, and in the other direction towards the Nordic EU Member States. The only other regions with household disposable income per inhabitant above the EU-28 average were in Spain: País Vasco, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, Comunidad de Madrid and Cataluña.

There were 43 regions that had lower household disposable income per inhabitant in 2016 than in 2008. Among these, 12 regions had above average household disposable income per inhabitant in 2016:

- País Vasco in Spain;

- Ireland;

- 10 central and northern Italian regions, including Lazio, the capital city region.

The 31 regions with below average household disposable income per inhabitant in 2016 and lower disposable income per inhabitant in 2016 than in 2008 included:

- all but one (Notio Aigaio) of the 13 regions of Greece;

- six southern and island regions in Italy.

The largest falls in household disposable income per inhabitant between 2008 and 2016 were in Greek regions and in Cyprus

In 11 of the 13 Greek regions, household disposable income per inhabitant fell by at least EUR 3 400 per inhabitant between 2008 and 2016, with the largest fall in Attiki (down EUR 5 800 per inhabitant). In Cyprus, disposable income fell by EUR 2 400 per inhabitant.

By contrast, 182 of the regions shown in Map 3 recorded a higher level of household disposable income per inhabitant in 2016 than in 2008. Of these, 51 regions recorded growth of less than EUR 1 000 per inhabitant, while 75 recorded growth of at least EUR 1 000 per inhabitant but less than EUR 3 000 per inhabitant. The remaining 56 regions recorded growth of at least EUR 3 000 per inhabitant, among which just one had household disposable income per inhabitant below the EU-28 average, namely the Lithuanian capital city region. Indeed, the vast majority of regions with relatively large increases in household disposable income per inhabitant also reported a level of income per inhabitant that was above the EU-28 average.

The highest increases in household disposable income per inhabitant between 2008 and 2016 were in regions of Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom and the northern EU Member States

The 56 regions with the highest rate of increase in household disposable income per inhabitant between 2008 and 2016 included:

- all regions of Denmark, Finland and Sweden;

- 20 British regions, mainly in southern England;

- 16 German regions.

In summary, the highest increases were all recorded in regions of northern EU Member States (all Nordic regions and one Baltic region), Germany, Austria and the United Kingdom. The largest increases of all were recorded in Inner London — West (where household disposable income rose by EUR 8 500 per inhabitant) and Outer London — West and North West (up EUR 6 000 per inhabitant), while 15 other regions recorded increases ranging between EUR 4 500 and EUR 5 700 per inhabitant, all of which were in London (two more regions), Denmark (all five regions) or Sweden (all eight regions).

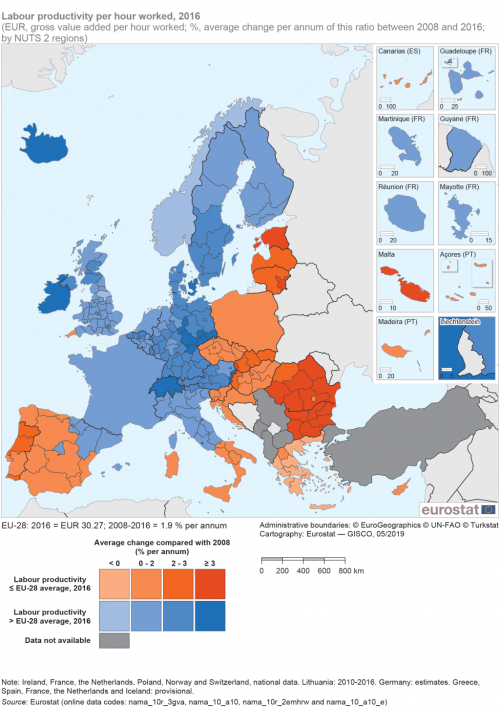

Labour productivity

Labour productivity may be defined as gross value added at basic prices expressed in relation to employment: in the analysis used in Map 4 the number of hours worked is used as the measure of labour input. Relatively high levels of labour productivity may be linked to an efficient use of labour (without using more inputs), or may result from the mix of activities within a local economy, as some activities — for example, extraction of oil and gas as well as business and financial services — are characterised by higher levels of labour productivity than others.

(EUR, gross value added per hour worked; %, average change per annum of this ratio between 2008 and 2016; by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10r_3gva), (nama_10_a10), (nama_10r_2emhrw) and (nama_10_a10_e)

As for the previous maps, regions which have a relatively high productivity — above the EU-28 average in 2016 — are shown in blue, while those that have a relatively low productivity are shown in orange. The lightest shade of orange and of blue indicate regions whose labour productivity in 2016 was below its 2008 level, in other words with a negative rate of change between these years. The other three shades of orange and of blue show regions with growth, darker shades indicating regions with stronger productivity growth. Information on labour productivity for Ireland, France, the Netherlands and Poland concern national rather than regional data, as is the case for Norway and Switzerland.

The highest labour productivity was EUR 76.26 per hour in Luxembourg and the lowest was EUR 5.42 per hour in Yuzhen tsentralen

Across the EU-28, there was an average of EUR 30.27 of added value for each hour worked in 2016. Among the 226 regions of the EU shown in Map 4 there were 85 with below average productivity and the remaining 141 were above average. The highest values recorded for this indicator were EUR 76.26 per hour in Luxembourg and EUR 70.91 per hour in Ireland, both countries that are strongly specialised in financial services. The lowest productivity was EUR 5.42 per hour in Yuzhen tsentralen (Bulgaria), resulting in a factor of 14.1 to 1 between the highest and lowest regions in the EU.

Higher than average labour productivity was concentrated in western and Nordic regions of the EU, as well as in parts of Spain and Italy

In 2016, the regions with labour productivity per hour above the EU-28 average included:

- all regions of Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, Austria, Finland and Sweden;

- Ireland, France and the Netherlands (only national data available);

- all regions of the United Kingdom, except for Cornwall and Isles of Scilly;

- 14 (out of 21) Italian regions, mainly northern and central, but also including Abruzzo;

- 7 (out of 19) Spanish regions (the capital city region and several regions in the north and east).

Therefore, none of the regions in eastern EU Member States or the Baltic Member States recorded above average productivity, while most southern regions also recorded below average productivity.

In nearly all EU Member States, the highest level of regional labour productivity was recorded in the capital city region. The four exceptions (among the Member States for which regional data are available) in 2016 were:

- Germany, where Hamburg had the highest labour productivity and Berlin the 26th highest out of 38 regions;

- Spain, where País Vasco had the highest productivity just ahead of the Comunidad de Madrid;

- Croatia, where Kontinentalna Hrvatska had higher productivity than Jadranska Hrvatska;

- Italy, where Lombardia had the highest productivity and Lazio the 6th highest out of 21 regions.

The regions where labour productivity was less than half the EU-28 average were exclusively from eastern or Baltic regions of the EU or from Greece

There were 34 regions in Map 4 where labour productivity was less than half the EU-28 average in 2016, including:

- Latvia (a single region at this level of detail) and one of two Lithuanian regions;

- Poland (only national data available);

- three Czech regions;

- all Bulgarian, Croatian and Hungarian regions;

- seven of eight Romanian regions;

- five Greek regions.

Turning to developments between 2008 and 2016, the average change in labour productivity in the EU-28 was an increase of 1.9 % per year. A total of 92 regions matched or bettered this increase, while 121 regions recorded smaller increases and 13 regions recorded decreases. Note that these changes are based on data in current prices.

The regions with lower productivity in 2016 than in 2008 were North Yorkshire in the United Kingdom and almost all Greek regions

The 13 regions with lower productivity in 2016 than in 2008 were North Yorkshire in the United Kingdom and 12 Greek regions; the only Greek region that recorded an increase in its labour productivity was Dytiki Makedonia. The only one of these 13 regions with a fall in productivity that had a level of productivity above the EU-28 average in 2016 was North Yorkshire.

Average increases of less than 2.0 % per year were recorded in 126 regions, in other words more than half of the regions. Somewhat faster increases were recorded in 61 regions, where productivity increased by at least 2.0 % but less than 3.0 % per year.

The fastest increase in productivity was in Yugoiztochen

There were 26 regions that recorded the fastest increases in productivity, averaging at least 3.0 % per year:

- 16 regions had a level of labour productivity in 2016 that was below the EU-28 average; they were mainly located in Bulgaria and Romania;

- 10 regions had above a level of labour productivity in 2016 that was above the EU-28 average; they were principally located in Denmark and Germany.

In fact, all six Bulgarian regions were in this group of regions with fast productivity growth, including Yugoiztochen which had the fastest average growth (7.2 % per year) among all regions of the EU.

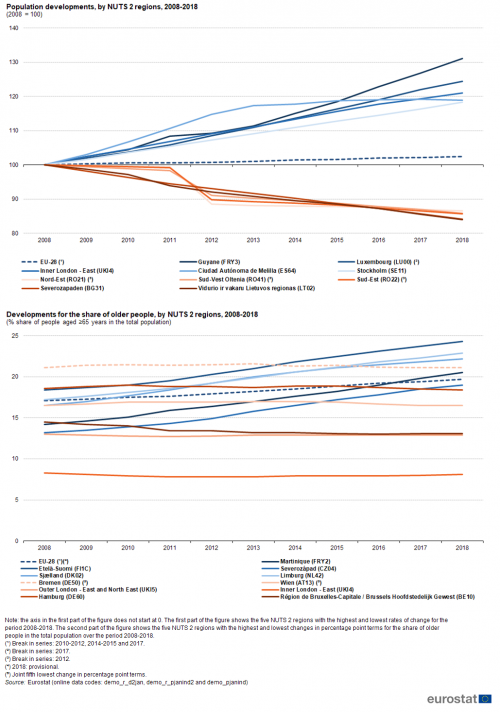

Population developments

The next analysis provides a description of changes in the total number of inhabitants living in NUTS level 2 regions between 2008 and 2018. Population change is driven by natural population change (the total number of births minus the total number of deaths) and net migration (the difference between the number of immigrants and emigrants); note that in the context of regional demography statistics, Eurostat produces net migration figures by taking the difference between total population change and natural change — hereafter referred to as net migration plus (statistical) adjustment.

There are wide-ranging differences in patterns of demographic change across the EU. Some of the most common medium-term developments may be summarised as follows:

- a capital city region effect, as populations continue to expand in and around many capital cities which exert a ‘pull effect’ on national and international migrants associated with (perceived) education and/or employment opportunities, as well as the potential to live a particular lifestyle;

- an urban-rural split, with the majority of urban regions continuing to report population growth, while the number of persons resident in many peripheral, rural and post-industrial regions declines;

- regional divergences within individual EU Member States which may impact on regional competitiveness and cohesion, for example, between the eastern and the western regions of Germany, or between northern and southern regions of Belgium, Italy and the United Kingdom.

About one third of EU regions recorded a lower level of population in 2018 than in 2008

In 2018, the EU-28’s population was 2.4 % higher than in 2008, up from 500 million to 512 million. About one third of the regions of the EU for which data are available recorded a lower population in 2018 than in 2008. EU Member States where at least half of the regions reported a fall included:

- Bulgaria, Estonia, Croatia, Latvia and Lithuania, where all regions reported a decline in population numbers;

- Hungary and Romania, where all of the regions except the capital city region reported a fall (for Hungary the data concerning the capital city region relate to NUTS level 1);

- Greece, Poland and Portugal, where a majority of the regions followed this pattern.

None of the regions in Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, Austria and Sweden had a lower population in 2018 than in 2008

By contrast, every region of Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, Austria and Sweden reported an increase in population numbers between 2008 and 2018. Six regions reported average growth of more than 1.5 % per year (including four capital city regions): Guyane (France), Luxembourg, Inner London — East, Ciudad Autónoma de Melilla (Spain), Stockholm and Malta.

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_d2jan), (demo_r_pjanind2) and (demo_pjanind)

In many of the EU Member States composed of more than one NUTS level 2 region the fastest population growth was recorded in the capital city region, although there were eight exceptions, including:

- Germany, where Oberbayern had faster growth than Berlin;

- Greece, where Voreio Aigaio had the fastest growth and Attiki had, in fact, the second fastest decrease among the 13 Greek regions;

- Spain, where the Ciudades Autónomas de Melilla y Ceuta, Illes Balears and Canarias had faster growth than the Comunidad de Madrid;

- France, where Guyane and eight other regions had faster growth than the Île de France.

In 2018, one fifth of the EU-28 population was aged 65 years or older

The bottom half of Figure 3 looks at the issue of ageing, in this case based on the share of the population aged 65 years or older. In the EU-28, this share was 19.7 % in 2018, up from 17.1 % in 2008. Changes in this share can reflect a number of different factors, such as developments for life expectancy, birth rates or migration. For example, an increase in the share of older people in a particular region might reflect older people moving into the region when they retire or younger people leaving the region (for example, to look elsewhere for education, work or other opportunities).

The Belgian capital city region, Hamburg and two London regions were the only regions in the EU to record a fall in their share of people aged 65 years or older

Only four regions in the EU recorded a fall in their share of older people (aged 65 years or older) between 2008 and 2018 (for some regions the time series is shorter): the Belgian capital city region (which had the largest reduction, down 1.4 percentage points (pp) from 14.5 % to 13.1 %), Hamburg and two London regions (all down 0.1-0.2 pp). In Bremen (Germany) and the Austrian capital city region the share of older people in the total population was stable, while elsewhere (275 regions) it increased.

There were 12 regions across the EU where the share of older people was at least 5.0 pp higher in 2018 than in 2008, for example:

- Severozápad, Severovýchod and Moravskoslezsko in Czechia;

- Friesland, Drenthe, Zeeland and Limburg in the Netherlands;

- Etelä-Suomi and Pohjois- ja Itä-Suomi in Finland.

As can be seen from the bottom half of Figure 3, the largest increase in this share was recorded in the French overseas region of Martinique, where the proportion of older people in the total population rose 6.3 pp from 14.2 % (below the EU-28 average of 17.1 %) in 2008 to 20.5 % in 2018 (above the EU-28 average of 19.7 %).

Working-age population — tertiary educational attainment

There is a range of policy challenges in relation to tertiary (higher) education (ISCED levels 5-8), among which: increasing participation (especially among disadvantaged groups); reducing drop-out rates and the time it takes some individuals to complete their course; making degree courses more relevant for the world of work. With a growing share of the EU-28 population having a tertiary level of educational attainment, some concerns have been expressed that certain regions have developed skills mismatches with a growing proportion of the labour force overqualified.

The tertiary educational attainment data shown in Map 5 are based on the share of the working-age population — defined here as 25-64 years — who had successfully completed a tertiary education programme; the lower age limit of 25 is used as most students have completed their tertiary education programmes before the age of 25.

Regions which have a relatively high level of tertiary educational attainment — above the EU-28 average in 2018 — are shown in blue, while those that have a relatively low level are shown in orange. The lightest shade of orange and of blue indicate regions whose level of tertiary educational attainment in 2018 was below its 2008 level, in other words with a negative rate of change between these years. The other three shades of orange and of blue show regions with growth in tertiary educational attainment, with darker shades indicating the regions with the strongest growth. The information in this map for Ireland and Lithuania relates to national rather than regional data, as is the case also for Serbia; the data for two Polish and two British regions are based on NUTS level 1 rather than level 2 regions.

In 2018, almost one third (32.3 %) of the EU-28 working-age population possessed a tertiary level of educational attainment; this was 8.1 pp higher than the corresponding share from a decade earlier.

The main characteristic of Map 5 is that capital city regions appear to act as a magnet for highly-qualified people. This was particularly true in several northern and western EU Member States, where capital city regions exerted considerable ‘pull effects’ through the varied employment opportunities that they could offer higher education graduates. This movement of graduates occurs not just within countries but also across national borders, with a growing share of the EU-28’s highly-qualified working-age population having moved internationally (in particular, moving from east to west within the EU).

More than half of the working-age population living in the Nordic capital city regions had a tertiary level of educational attainment

In 2018, there were 109 NUTS level 2 regions where the share of the working-age population (25-64 years) that had a tertiary level of educational attainment was above the EU-28 average, among which there were eight where the share passed 50 %. Three of these regions — London (NUTS level 1) and two of its neighbouring regions (Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire; Surrey, East and West Sussex) — were in the United Kingdom. Three more were capital city regions of the Nordic Member States (Denmark, Finland and Sweden), while Utrecht in the Netherlands and Prov. Brabant Wallon neighbouring the Belgian capital city region completed the list.

By contrast, among the 154 regions where the share of the working-age population that had a tertiary level of educational attainment was equal to or below the EU-28 average, 26 regions reported that this share was below 20 %. These were often rural regions characterised as local economies concentrated on agriculture, with a generally low level of demand for highly-skilled labour, including:

- Közép-Dunántúl, Dél-Dunántúl, Észak-Magyarország and Észak-Alföld in Hungary;

- 12 regions across Italy;

- all Romanian regions except for the capital city region.

There were six regions in eastern Germany where the share of the working-age population with a tertiary level of educational attainment declined between 2008 and 2018

Looking at the change between 2008 and 2018 in the share of the population aged 25-64 that had a tertiary level of educational attainment, the vast majority of regions recorded an increase. In fact, only six regions reported a lower share in 2018 than in 2008, all of them within Sachsen or Sachsen-Anhalt in eastern Germany. Leipzig — which was the only one of the six with a share above the EU-28 average in 2018 — and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern recorded falls of 1.1 pp, the smallest declines among these six regions. The largest fall was in Chemnitz where the share of the working-age population with a tertiary level of educational attainment fell from 30.4 % in 2008 to 24.7 % in 2018.

Increases of less than 5.0 pp between 2008 and 2018 were observed in 53 regions, while increases of at least 5.0 pp but less than 10.0 pp were recorded in 136 regions. At the other end of the range, some 68 regions reported increases of 10.0 pp or more. They were distributed across northern (seven regions), southern (eight), eastern (13), and western (40) EU Member States — the latter including every region of Austria.

(%, share of persons aged 25-64 years with a tertiary level of educational attainment; percentage points, change of this share between 2008 and 2018; by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_04)

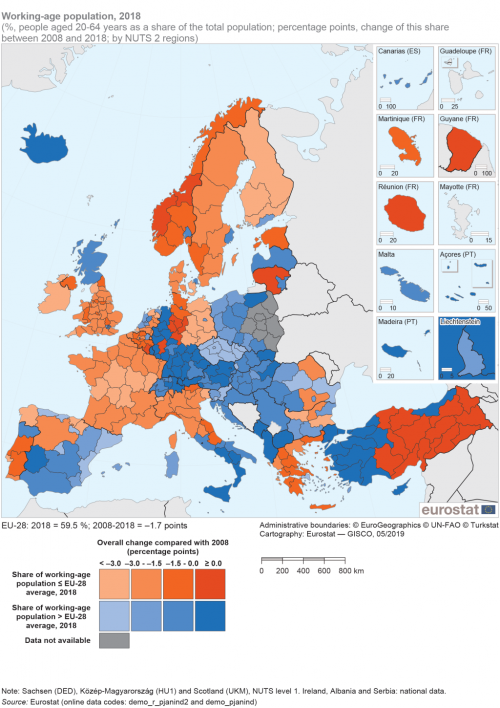

Relative size of the working-age population

Map 6 also focuses on the working-age population, in this case using a slightly broader age range, from 20-64 years. Within this age range some people, particularly younger ones may still be studying and so not actually in the labour force. Equally, some people in the labour force are outside this age range if they are working before the age of 20 years or still working when aged 65 years or older. The share of working-age people in the population is influenced by many factors, such as changes in birth rates, death rates, life expectancy and net migration (plus statistical adjustment).

The issue of an ageing population has already been mentioned with respect to Figure 3, which provided information for regional developments in the share of the population aged 65 years and over. Many of the comments noted there can be expected to apply here, but in reverse, as those regions with a relatively high or increasing share of older people tend to have a relatively low or falling share of people of working age.

In 2018, the average share of the working-age population in the total number of inhabitants was 59.5 % in the EU-28, which was 1.7 pp lower than in 2008. Among the 281 NUTS level 2 regions for which 2018 data are available, 137 recorded a share above the EU-28 average in and 144 equal to or below the EU-28 average. Of the 272 regions that are represented in Map 6 (some regions are shown at NUTS level 1 to allow a time series analysis), nine are not available (due to missing data for 2008), leaving 125 regions coloured blue (with above average shares) and 138 regions coloured orange.

In 2018, the highest shares of the working-age population were in Inner London regions

Considering all 272 of regions across the EU (as shown in Map 6), the highest shares of the working-age population in 2018 were in two of the British capital city regions, Inner London — East and Inner London — West (68.2 % and 67.3 % respectively). The Romanian capital city region (Bucureşti-Ilfov) and the Spanish island region Canarias also recorded shares above 65.0 %. By far the lowest share in 2018 was in Mayotte (shown as not available in Map 6 as data for 2008 are missing), which was the only region in the EU where less than half (43.5 %) of the population were of working age. The next five lowest shares for the working-age population were also in France, with shares ranging from 52.9 % in Guyane to 54.0 % in Bourgogne. In fact, the bottom 25 regions with the lowest shares — no higher than 55.5 % — were all located in France, the United Kingdom or the Nordic EU Member States; most of them were coastal regions, although five of the French regions were exceptions to this rule.

A total of 49 regions — mainly in Germany, Austria and Italy — recorded an increase or no change in the share of the working-age population between 2008 and 2018

The intensity of the blue and orange shading in Map 6 indicates the speed with which the share of the working-age population changed between 2008 and 2018 in the 263 regions of the EU for which data are available. A total of 49 regions recorded an increase or no change in this share. Nearly half of these regions (24) were in Germany while six more were in Austria and four in Italy; 11 other EU Member States had either one or two regions that experienced an expansion or stability in the share of their working-age population. The only region in the northern Member States to record an increase in the share of the working-age population was Vidurio ir vakarų Lietuvos regionas in Lithuania, while Warmińsko-mazurskie in Poland and Východné Slovensko in Slovakia were the only such regions in the eastern Member States. The single largest increase was in the Portuguese Região Autónoma dos Açores, where the share rose 2.5 pp from 60.9 % in 2008 to 63.4 %. The increase of 2.1 pp in Luxembourg was the second highest increase, followed by an increase of 1.7 pp in neighbouring Trier (Germany).

The largest fall in the share of the working-age population was in País Vasco in Spain, where the share decreased from 64.6 % in 2008 to 59.0 % in 2018

The share of the working-age population fell by at most 1.5 pp between 2008 and 2018 in 72 regions, while some 93 regions reported a fall in the share that was larger than 1.5 pp, but at most 3.0 pp. The final group of regions — those with the lightest shade of blue and orange in Map 6 — recorded falls of more than 3.0 pp in this share. These 49 regions were spread across 16 different EU Member States, most notably Spain (nine regions), Czechia (all eight regions), France (six), Germany (five), the Netherlands, Finland and the United Kingdom (three each). The largest fall of all was in País Vasco (Spain), where the share of the working-age population decreased 5.6 pp from 64.6 % in 2008 to 59.0 % in 2018. The next largest falls (between 4.3 and 4.9 pp) were recorded in five Czech regions (including the capital city region), as well as in the capital city regions of Slovakia, Portugal and Spain.

(%, people aged 20-64 years as a share of the total population; percentage points, change of this share between 2008 and 2018; by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_pjanind2) and (demo_pjanind)

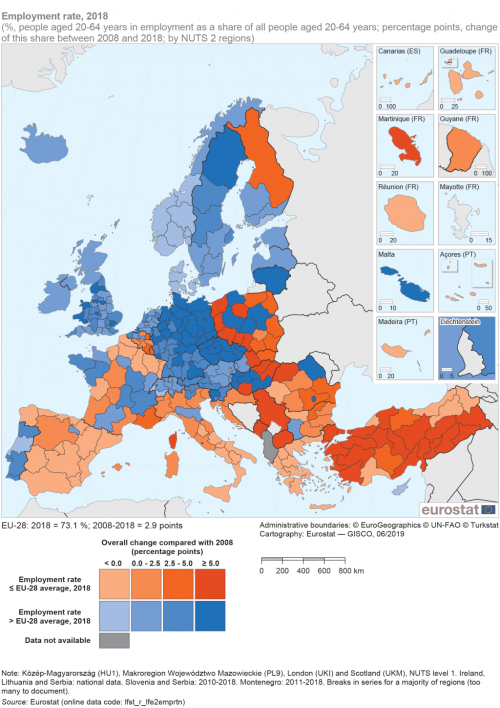

Employment rate

The final analyses in this chapter move on from the population of working age to employment within the same age range. The employment rate is the ratio of employed persons (of a given age) relative to the total population (of the same age); for this section, information is presented on the rate for people aged 20-64 years. This definition aims to ensure compatibility at the lower end of the age range, given that an increasing proportion of young people remain within educational systems, which may exclude them from participating in labour markets. At the upper end of the range, rates are usually set to a maximum of 64 years, taking into account (statutory) retirement or pension ages in some parts of the EU. Note however that policymakers are increasingly looking to extend retirement/pensionable ages and in the future it is likely that a greater share of older persons will remain in the labour force.

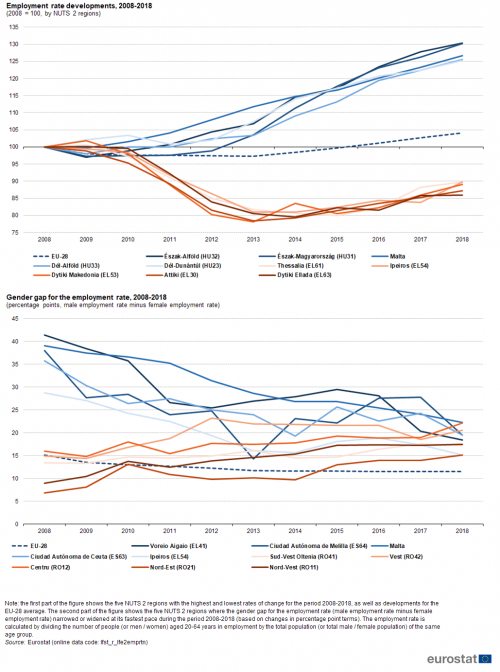

The Europe 2020 strategy set a benchmark target, as part of its agenda for growth and jobs, whereby 75 % of all 20-64 year-olds should be employed by 2020. The EU-28 employment rate for people aged 20-64 stood at 73.1 % in 2018, marking its fifth consecutive increase since a relative low of 68.3 % in 2013. The EU-28 employment rate in 2018 was 2.9 pp higher than 10 years earlier.

Map 7 presents employment rates for people aged 20-64 across NUTS level 2 regions. The 158 regions with rates above the EU-28 average are shown in blue and the 109 regions with rates equal to or below the average are shown in orange. The lightest shades show regions with rates that were lower in 2018 than in 2008, while the other shades show regions where rates increased over this period, with the largest increases shown in the darkest shades.

(%, people aged 20-64 years in employment as a share of all people aged 20-64 years; percentage points, change of this share between 2008 and 2018; by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_lfe2emprtn)

Apart from Pohjois- ja Itä-Suomi in Finland, all regions in northern EU Member States reported above average employment rates; note that only national data are available for Lithuania. By contrast, most regions in southern Member States had below average employment rates, as was the case in all regions of Greece and nearly all of Spain and Italy; nevertheless, Cyprus and Malta had above average employment rates as did most Portuguese regions. Among eastern EU Member States, Croatian regions had below average employment rates as did most regions in Bulgaria, Poland and Romania. Half the Slovakian regions had above average employment rates, as did a small majority of Hungarian regions and all regions in Czechia and Slovenia. Among western Member States, the situation was also mixed: Luxembourg had a below average employment rate as did most Belgian and French regions; all but one (the capital city region) of the Austrian regions had above average employment rates, as did all regions in Germany, Ireland (only national data available), the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

The highest regional employment rates in the EU were recorded in Stockholm and Åland

The regions with the highest employment rates had some of the most dynamic labour markets, often characterised by low levels of unemployment and a relatively high share of women in work. In 2018, the highest rate across all EU regions was 85.7 % in Stockholm, followed closely by Åland (85.1 %). In general, the highest employment rates were in regions of Germany, Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom, along with the Czech capital city region. By contrast, the lowest employment rates were recorded in regions of Belgium, Greece, Spain and Italy, as well as the French overseas regions. Five regions recorded employment rates below 50 %, four of which were southern or island regions of Italy and the fifth — with the lowest rate of all (40.8 %) — was Mayotte (shown as not available in Map 7 as 2008 data are missing).

The largest increases in the employment rate were in Hungarian regions

There were 68 regions in the EU where the employment rate rose by at least 5.0 pp between 2008 and 2018. Among these, there were 15 where the increase was at least 10.0 pp, with six regions in Hungary and three in Poland. The top half of Figure 4 shows the five regions with the largest increases in percentage terms — which also had the largest increases in percentage point (pp) terms — four of which were in Hungary. The largest increase was in Észak-Alföld, where the employment rate rose by 16.6 pp, from 54.7 % in 2008 to 71.3 % in 2018.

(2008 = 100, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_lfe2emprtn)

The employment rate increased by at least 2.5 pp but less than 5.0 pp between 2008 and 2018 in 63 regions, while 77 regions reported a stable or moderate increase (less than 2.5 pp).

The largest decreases in the employment rate were in Greek regions

The final group of regions — those with the lightest shade of blue and orange in Map 6 — recorded a lower employment rate in 2018 than in 2008. This group included 59 regions, mainly in Spain (15 regions), Greece (all 13 regions), France (nine), Italy (nine) and Denmark (all five regions), although there were also three regions in Portugal, two in Finland and one each in Bulgaria, Cyprus and Romania. The nine regions with the largest falls in employment rates were all in Greece, eight of which had a decline that was in excess of 6.0 pp. The largest fall was recorded in Dytiki Ellada where the employment rate in 2018 was 53.7 %, down 8.8 pp from 62.5 % in 2008.

The bottom half of Figure 4 provides an insight into the gender imbalance of the labour market. During the financial and economic crisis the gender gap for the EU-28’s employment rate narrowed rapidly, falling from 15.1 pp in 2008 to 11.7 pp in 2013, before stabilising at 11.5 pp between 2016 and 2018. The regions that are shown in the bottom half of the figure are those where the gender gap for the employment rate narrowed or widened at its fastest pace during the period 2008 to 2018 (based on changes in percentage point terms).

In fact, there were only 26 NUTS level 2 regions in the EU where the gender gap for the employment rate widened between 2008 and 2018 and three more where it was the same in both years. These regions were mainly in Poland, Romania and Hungary, with a few regions also in France, Germany, the United Kingdom and Sweden. The largest expansions in this gender gap were 8.6 and 8.3 pp in the Nord-Vest and Nord-Est regions of Romania; the gender gaps recorded in these regions were approximately twice as high in 2018 as they had been in 2008.

In the remaining 232 regions, the gender gap for the employment rate was narrower in 2018 than in 2008. In 11 regions the gap narrowed by more than 10 pp, with this difference reaching 23.0 pp in Voreio Aigaio (Greece). These regions with a particularly large contraction in the gender gap for the employment rate were nearly all in southern EU Member States — Spain, Greece, Portugal and Malta — but included also Haute-Normandie (France).

Source data for figures and maps

Data sources

National accounts

The European system of national and regional accounts (ESA 2010) is the latest internationally compatible accounting framework for a systematic and detailed description of the EU economy. ESA 2010 has been implemented since September 2014 and is consistent with worldwide guidelines on national accounting, as set out in the system of national accounts (2008 SNA). ESA 2010 ensures that economic statistics for EU Member States are compiled in a consistent, comparable, reliable and up-to-date way. The legal basis for these statistics is a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the European system of national and regional accounts in the European Union (Regulation (EU) No 549/2013).

ESA 2010 is not restricted to annual national accounting, as it also applies to quarterly and shorter or longer period accounts, as well as to regional accounts. It is harmonised with the concepts and classifications used in many other social and economic statistics (for example, statistics on employment, business or international trade) and as such serves as a central reference for socioeconomic statistics.

Statistics from regional economic accounts are largely shown for NUTS level 2 regions. The data for statistical regions in the EFTA and candidate countries are often unavailable and have been replaced (where appropriate) by national aggregates. Note also that the data for these countries are sometimes less fresh than for EU regions; all discrepancies are footnoted under maps or figures.

For more information:

ESA 2010 — manuals and guidelines

Population

Eurostat collects a wide range of regional demographic statistics: these include data on population numbers and various demographic events which influence the population’s size, structure and specific characteristics. Regional demographic statistics may be used for a wide range of planning, monitoring and evaluating actions, for example, to:

- analyse population ageing and its effects on sustainability and welfare;

- evaluate the economic impact of demographic change;

- calculate per inhabitant ratios and indicators — such as regional GDP per inhabitant, which may be used, for example, to allocate structural funds to economically less advantaged regions.

For more information:

Dedicated section for population

Tertiary education

As the structure of education systems varies from one country to another, a framework for assembling, compiling and presenting regional, national and international education statistics is a prerequisite for the comparability of data and this is provided by the international standard classification of education (ISCED). ISCED 2011 provides the basis for the statistics presented in this article: it was adopted by the UNESCO General Conference in November 2011. Tertiary education comprises ISCED levels 5 to 8.

Most EU education statistics are collected as part of a jointly administered exercise that involves the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UNESCO-UIS), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and Eurostat, often referred to as the UOE data collection exercise; data on regional enrolments are collected separately by Eurostat. However, information on tertiary educational attainment is compiled from the EU’s labour force survey (see below).

For more information:

International standard classification of education (ISCED 2011)

Dedicated section for education statistics

Labour force

The data for tertiary educational attainment and the employment rate that are presented in this article pertain to annual averages derived from the labour force survey. This survey covers more than 30 countries, comprising the EU Member States, three EFTA countries (Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) and four candidate countries (Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey). The survey population generally consists of persons aged 15 and over living in private households, with definitions aligned with those provided by the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

When analysing regional information from the LFS, it is important to bear in mind that the information presented relates to the region where the respondent has his/her permanent residence and that this may be different to the region where their place of work is situated as a result of commuter flows.

For more information:

Context

Just over a decade has passed since the global financial and economic crisis started. The analyses presented here look at the impact of the crisis the pace at which regions have bounced back or have been left behind. To put this into context, the following section provides a brief summary of how events unfolded in the EU-28.

Annual measures of GDP show a peak value for the EU-28 in 2008, although annual growth (0.5 %) was already considerably lower than it had been in 2007 (3.1 %). In fact, quarterly data indicate that the rate of change for overall economic activity had already turned negative by the second quarter of 2008. Employment in the EU-28 also peaked in 2008, with growth (1.1 %) just over half the level recorded in 2007 (1.9 %). A quarterly time series of employment shows a slightly later impact of the crisis: in the second quarter of 2008 the level of employment was unchanged (0.0 %) and there was growth (0.1 %) in the third quarter, such that it was not until the fourth quarter of 2008 that a sustained series of quarter on quarter falls in the level of employment began. Unsurprisingly, these developments are reflected in the unemployment rate: the annual rate for the EU-28 was 7.3 % in 2008, down from 7.5 % in 2007; the quarterly unemployment rate fell most quarters between the middle of 2005 to reach a low of 6.8 % in the first quarter of 2008 and was relatively stable in quarters 2 and 3 (rising by 0.1 % in each quarter), however, it was not until the fourth quarter of 2008 that the EU-28 unemployment rate started to record a sustained increase (up 0.4 %) resulting from the impact of the crisis.

A timeline for the causes of the crisis as a whole can be established: falling house prices in the United States in 2006 lead to a crisis in the United States’ subprime mortgage market in 2007, which in turn lead to difficulties for some mortgage lenders, banks and insurance companies in 2007 which in 2008 became a global financial crisis (as witnessed through a global economic slowdown and recession). While the data presented above show how and when its impact started to be observed in the EU-28 as a whole (for a selection of key indicators), the impact of the crisis became apparent at different times among the EU Member States and also at different times among the regions; not only did the timing of the crisis vary between countries and regions, but also the extent of the economic damage and subsequent recovery.

The analyses in this chapter focus on annual data, taking 2008 as the starting point, reflecting peak economic output (as measured by GDP) and peak employment in the EU-28.

European Pillar of Social Rights

The European Pillar of Social Rights was primarily conceived for the euro area, but is open to all EU Member States wishing to participate. It aims to take into account the changing realities of the world of work, serve as a compass for a renewal of convergence within the euro area, and deliver new and more effective rights for citizens. It was jointly signed by the European Parliament, the Council and the European Commission in November 2017. It has 20 principles grouped within three main categories.

For more information:

European Commission: European Pillar of Social Rights

General Directorate Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion: European Pillar of Social Rights

GDP and beyond

In August 2009, the European Commission adopted a communication GDP and beyond: measuring progress in a changing world (COM(2009) 433 final), which outlined a range of actions to improve and complement GDP measures. This noted that there was a clear case for complementing GDP with statistics covering other economic, social and environmental issues, on which individuals’ well-being critically depends. A set of complementary indicators was detailed in a staff working paper Progress on GDP and beyond actions (SWD(2013) 303 final), including regional and local indicators.

Direct access to

Regional statistics

- Population statistics at regional level

- Education and training statistics at regional level

- Labour market statistics at regional level

- Economy at regional level

Population

Education

- Education and training in the EU — facts and figures (online publication)

Labour market

- EU labour force survey — online publication

- EU labour force survey statistics — online publication

- Employment - annual statistics

National accounts

- Regional demographic statistics (t_reg_dem)

- Regional economic accounts - ESA2010 (t_nama_10reg)

- Regional education statistics (t_reg_educ)

- Regional labour market statistics (t_reg_lmk)

- Regional demographic statistics (reg_dem)

- Regional economic accounts (reg_eco10)

- Regional education statistics (reg_educ)

- Regional labour market statistics (reg_lmk)

- Population (demo_pop)

- Regional data (demopreg)

- Education and training outcomes (educ_outc)

- Educational attainment level (edat)

- Population by educational attainment level (edat1)

- Educational attainment level (edat)

- LFS series - Specific topics (lfst)

- LFS regional series (lfst_r)

- Regional employment - LFS annual series (lfst_r_lfemp)

- LFS regional series (lfst_r)

- Auxiliary indicators (population, GDP per capita and productivity) (nama_10_aux)

- Basic breakdowns of main GDP aggregates and employment (by industry and by assets) (nama_10_bbr)

- Regional economic accounts (nama_10reg)

- Gross domestic product indicators (nama_10r_gdp)

- Branch and Household accounts (nama_10r_brch)

Manuals and online methodological publications

- Labour force survey methodology — main concepts

- Methodological manual on territorial typologies — Eurostat — 2018 edition

- Manual on regional accounts methods — 2013 edition

Metadata

- Population (ESMS metadata file — demo_pop_esms)

- Regional economic accounts (ESMS metadata file — reg_eco10_esms)

- Regional education statistics (ESMS metadata file — reg_educ_esms)

- Regional labour market statistics (ESMS metadata file — reg_lmk_esms)

- European Commission — Education and Training — Strategic framework — Education & Training 2020

- European Commission —Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion — European employment strategy

- European Commission — European Pillar of Social Rights

- European Commission — Regional and Urban Policy — European Structural and Investment Funds (ESI Funds)

.

Maps can be explored interactively using Eurostat’s statistical atlas (see user manual).

This article forms part of Eurostat’s annual flagship publication, the Eurostat regional yearbook.