Living conditions statistics at regional level

Data extracted in July 2023.

Planned article update: September 2024.

Highlights

In 2022, Sud-Est in Romania and Campania in Italy were the only regions in the EU to report that more than 45.0 % of their populations were at risk of poverty or social exclusion.

The EU’s material and social deprivation rate was 12.7 % in 2022: there was a considerable range across EU regions, from a low of 2.1 % in Zeeland (the Netherlands) up to a high of 47.1 % in Sud-Est (Romania).

By global standards, most people living in the European Union (EU) are relatively prosperous. This likely reflects the EU’s high income/wealth levels and its network of established social protection systems that provide a safety net for many of the less fortunate. Nevertheless, 95.3 million people in the EU (21.6 % of the population) were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2022 (see the infographic above for more information).

Sociodemographic characteristics like age, educational attainment, sex, country of birth / citizenship can play an important role in shaping an individual’s living conditions. Wider societal developments, such as the impact of globalisation, coupled with unexpected shocks – for example, the global financial and economic crisis, the COVID-19 crisis, the impact of Russian military aggression against Ukraine, or the cost-of-living crisis – can also have a considerable impact. In some cases, these events can rapidly undo long-term decreases in inequality, thereby reinforcing or exacerbating patterns of inequality and exclusion.

Having shown signs of a gradual fall in inequality prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the crisis reinforced some of the well-established inequalities in living conditions both between and within individual EU Member States. While some people were fortunate enough to continue working full-time from home (and in some cases were even able to save more of their income than usual), frontline and key workers faced increased health risks. Many people in precarious employment or working in sectors/businesses impacted by successive lockdowns faced reduced wages/earnings, short-time work (furlough schemes / temporary lay-offs / technical unemployment) and unemployment. Indeed, the asymmetric impact of the crisis was such that it may have exacerbated existing inequalities, with vulnerable groups in society being disproportionately impacted.

For more than a year, people in the EU have witnessed a considerable increase in the cost of living. Rising prices for goods like energy and food are felt across all socioeconomic groups. However, they tend to have a greater impact on the poorest individuals in society, as they usually allocate a larger proportion of their disposable income to such ‘essential goods’. The EU’s annual inflation rate accelerated from 0.7 % in 2020 to 9.2 % by 2022. This surge in prices experienced across the EU can be attributed, at least in part, to Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine. For example, the price of natural gas and oil increased as a result of concerns over supply shortages (with international sanctions placed on Russian energy exports), while foodstuffs and fertilisers also saw their prices rise, as the export capacity of Ukraine and Russia was cut due to the direct impact of the war. Another contributing factor to rising inflation was a post-pandemic surge in demand for a number of relatively scarce products/materials.

Full article

People at risk of poverty or social exclusion

There are two ways that poverty can be measured. According to the United Nations, absolute poverty is the deprivation of basic human needs, for example, a lack of food, shelter, water, sanitation facilities, health or education (in other words, where a household’s income is insufficient to afford the basic necessities of life). By contrast, relative poverty concerns the situation where a household’s income is below a certain percentage of the median household income of the country where they live (in other words, they do not have enough income to enjoy a ‘normal’ standard of living for the society in which they live).

The indicator for people at risk of poverty or social exclusion is based on measures of relative poverty, severe material and social deprivation and quasi-joblessness. The number/share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion (see the infographic at the start of this chapter) combines these three criteria covering people who are in at least one of the following situations:

- at risk of poverty – people with an equivalised disposable income (after social transfers) below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income;

- facing severe material and social deprivation – people unable to afford at least 7 out of 13 deprivation items (six related to the individual and seven related to the household) that are considered desirable (or even necessary) to lead an adequate quality of life;

- living in a household with very low work intensity – where working-age adults (aged 18–64, excluding students aged 18–24 and those who are retired) worked for 20 % or less of their combined potential working time during the previous 12 months.

On 4 March 2021, the European Commission set out its ambition for a stronger social EU to focus on education, skills and jobs, paving the way for a fair, inclusive and resilient socioeconomic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, while fighting discrimination, tackling poverty and alleviating the risk of exclusion for vulnerable groups. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan outlines a set of commitments from policymakers and provides three key targets for monitoring progress. One of these targets is to reduce the number of people in the EU at risk of poverty or social exclusion between 2019 and 2030 by at least 15 million persons (of which, at least five million should be children).

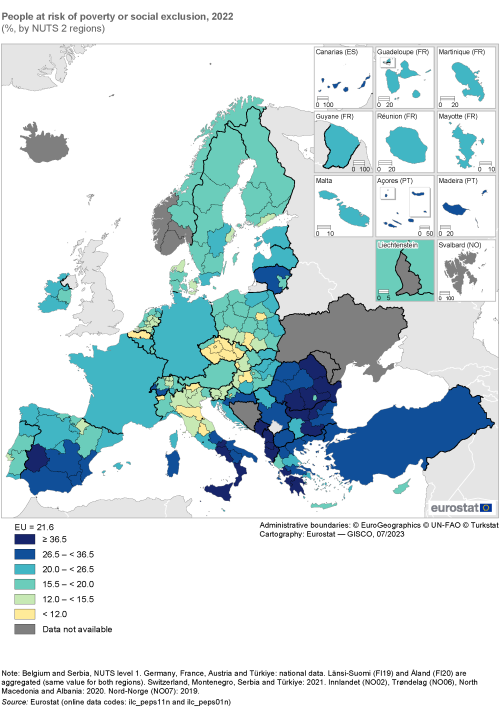

Some 21.6 % of the EU population was at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2022

Map 1 shows the regional distribution of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion for NUTS level 2 regions. Note that the statistics presented for Belgium and Serbia relate to level 1 regions and that only national data are available for Germany, France, Austria and Türkiye. In 2022, the regional distribution of the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion was somewhat skewed, as approximately two fifths of all regions in the EU (66 out of the 163 for which data are available) recorded shares above the EU average. Given that the national averages for Germany, France and Austria are all below the EU average, it is possible that the regional distribution would be even more skewed if regional data were available for these three EU Member States.

At the top end of the ranking, there were 17 regions across the EU where the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion was at least 36.5 % in 2022; they appear in the darkest shade of blue in Map 1. Most of this group was composed of regions located in Bulgaria, Greece or Romania, or regions located in southern parts of Spain and Italy. Sud-Est in Romania (46.9 %) and Campania in southern Italy (46.3 %) had the highest shares. They were followed by another Romanian and another southern Italian region, namely, Sud-Vest Oltenia (44.7 %) and Calabria (42.8 %). There were four more regions across the EU – Severozapaden (Bulgaria), Sicilia (Italy) and the two autonomous Spanish regions of Ciudad de Melilla and Ciudad de Ceuta – where more than two fifths of the population were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2022. Note that despite being one of the most affluent regions in the EU, more than one third (38.8 %) of the population was at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the Belgian Région De Bruxelles-Capitale / Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest (NUTS level 1).

A low proportion of people were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in a cluster of regions principally spread across eastern EU Member States. In 2022, there were 16 regions where less than 12.0 % of the population were at risk of poverty or social exclusion; they are shown in a yellow shade. This group was concentrated in Czechia (six out of eight regions) and also included two regions of Poland, as well as single regions from Slovakia, Croatia and Hungary. The remainder of this group was composed of four regions located in northern and central Italy, as well as single (NUTS level 1) region from Belgium. Looking in more detail, there were five regions within the EU where less than 1 in 10 people were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2022:

- the Polish and Czech capital regions of Warszawski stołeczny (7.7 %) and Praha (8.9 %), the former recording the lowest share in the EU;

- the Italian regions of Valle d’Aosta/Vallée d’Aoste (8.6 %) and Emilia-Romagna (9.6 %); and

- Střední Čechy (8.7 %), which surrounds the Czech capital region.

While living in a capital region may often appear an attractive proposition – better education and employment opportunities, enhanced infrastructure, improved public services and a broader range of cultural and social experiences – there are also challenges for people living in capital regions, such as higher living costs, increased competition, or a risk of isolation. People living in the capital regions of eastern EU Member States were less likely to be at risk of poverty or social exclusion than their counterparts living in the remainder of the country. For example, the proportion of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion across Poland (15.9 %) in 2022 was 2.1 times as high as the share recorded in its capital region of Warszawski stołeczny. A similar pattern was observed in Romania and in Croatia. In the former, the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion was 34.4 %, which was 1.8 times as high as the share recorded in the capital region of Bucureşti-Ilfov (19.2 %). Almost one fifth (19.9 %) of the population in Croatia was considered to be at risk of poverty or social exclusion, which was 1.8 times as high as the share recorded in the capital region of Grad Zagreb (11.2 %). This pattern was repeated, although to a lesser extent, in the other eastern EU Member States.

By contrast, the situation was reversed in three Member States. As already noted, the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the Belgian capital Région De Bruxelles-Capitale / Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest (NUTS level 1) was relatively high, at 38.8 %; indeed, it was more than twice as high (2.1 times) as the national average for Belgium. While regional differences across Denmark and the Netherlands were modest, the Danish and Dutch capital regions of Hovedstaden and Noord-Holland also recorded above average shares of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Hovedstaden had the second highest share among the five regions of Denmark (behind Syddanmark), while Noord-Holland had the third highest share among the 12 regions of the Netherlands.

(%, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_peps11n) and (ilc_peps01n)

Figure 1 identifies the EU regions with the highest and lowest shares of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2022. It also shows the regions with the biggest changes in their respective shares between 2021 and 2022. Overall, there was no significant change across the EU, as the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion fell 0.1 percentage points from 21.7 % to 21.6 % during this period.

Across the 163 NUTS level 2 regions for which data are available (note that the statistics presented for Belgium relate to NUTS level 1 regions and that only national data are available for Germany, France and Austria), the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion rose in 71 regions between 2021 and 2022, remained unchanged in two regions and fell in 90. The six regions with the highest increases were all located in eastern or southern EU Member States: two regions in Italy, together with single regions from each of Spain, Romania, Slovakia and Poland. Leaving aside the atypical Spanish region of Ciudad de Melilla, the largest increase was recorded in the Romanian region of Sud-Vest Oltenia (up 5.6 percentage points).

The regions with the biggest falls in their respective shares of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion were (also) largely composed of regions located in eastern and southern EU Member States: three regions in Greece, two in Italy and in Poland, and single regions from each of Portugal and Romania; Flevoland in the Netherlands also had a large fall. The high level of regional variations observed in some eastern and southern EU Member States may reflect, at least to some degree, less comprehensive social safety nets, such that their shares of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion fluctuate more in line with underlying economic fortunes. Between 2021 and 2022, the biggest decrease in the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion was recorded in the Greek island region of Kriti, down 11.0 percentage points (from 28.8 % to 17.8 %).

(by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_peps11n) and (ilc_peps01n)

People at risk of poverty

The at-risk-of-poverty rate (after social transfers) is one of the three criteria used to identify people at risk of poverty or social exclusion. It identifies the proportion of the population who live in a household with an annual equivalised disposable income that is below 60 % of the national median. Note that at-risk-of-poverty rates do not measure poverty itself, rather they provide information on the share of the population with a level of income that is below a threshold which is set separately for each EU Member State.

The at-risk-of-poverty rate before social transfers measures a hypothetical situation where social transfers are absent; note that pensions, such as old-age and survivors’ (widows’ and widowers’) benefits, are counted as income (before social transfers) and not as social transfers. When comparing at-risk-of-poverty rates before and after social transfers it is possible to assess the impact and redistributive effects of welfare policies. These transfers cover assistance that is given by central, state or local institutional units and include, among other types of transfers, unemployment benefits, sickness and invalidity benefits, housing allowances, social assistance and tax rebates. Note that for statistics on income, the reference period generally refers to the calendar year before the year in which the survey took place.

In 2022, the reduction in the EU’s at-risk-of-poverty rate due to the impact of social transfers was 9.0 percentage points, with a rate of 25.5 % before social transfers and 16.5 % after. There was a relatively clear geographical divide in terms of the redistributive impact of social transfers and the extent to which they reduce the risk of monetary poverty. These differences reflect, among other influences, historical, political, economic and cultural factors. Social transfers had a particularly high impact across regions of the Nordic Member States, Belgium and Ireland. By contrast, their impact was relatively low – in percentage point terms – across many regions of the Baltic, eastern and southern EU Member States.

Figure 2 is split into two parts: the left-hand side presents the regions in the EU with the highest and lowest at-risk-of-poverty rates before social transfers. Prior to social transfers, there were seven regions in the EU where upwards of two fifths of the population faced the risk of monetary poverty in 2022. The Italian region of Campania had the highest share (51.0 %) and was the only region in the EU where the risk of monetary poverty prior to social transfers impacted more than half of the population. The other six regions with rates above 40.0 % included four more regions from southern Italy – Sicilia, Calabria, Sardegna and Molise – as well as the capital region of Belgium and the Bulgarian region of Severozapaden.

After taking account of the redistributive impact of social transfers, none of the seven regions mentioned above reported that more than two fifths of their populations were at risk of monetary poverty. Nevertheless, all seven regions featured near the top of the ranking for those regions with the highest at-risk-of-poverty rates after social transfers (see the right-hand side of Figure 2). In 2022, Campania (37.1 %) and Sicilia (36.8 %) had the highest rates, while more than 3 in 10 people also continued to experience such a risk after social transfers in Calabria (34.5 %), Severozapaden (33.8 %), Sardegna (30.8 %) and Molise (30.5 %); this was also the case for one other region – Sud-Vest Oltenia in Romania (34.7 %). By contrast, social transfers played a greater role in reducing the risk of poverty in several Irish, Danish and Belgian regions:

- the biggest reductions – in percentage point terms – were recorded in the Irish regions of Southern (down 21.1 points) and Northern and Western (down 18.9 points), while the capital region of Eastern and Midland also recorded a considerable fall (down 16.0 points);

- large reductions were recorded in two out of the three NUTS level 1 regions of Belgium, as the redistributive impact of social transfers was considerable in Région de Bruxelles-Capitale / Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest (down 16.8 percentage points) and in Région wallonne (down 16.3 points);

- in the Danish regions of Nordjylland and Midtjylland, the redistributive impact of social transfers was such that the share of the population facing the risk of poverty was reduced by 16.4 and 15.5 percentage points, respectively.

Looking in more detail at the EU regions with the lowest risks of monetary poverty (as shown in the bottom half of the right-hand chart), most were characterised by a relatively low risk of monetary poverty both before and after the redistributive impact of social transfers. For example, in the Romanian capital region of Bucureşti-Ilfov, the at-risk-of-poverty rate stood at 5.9 % before social transfers; the impact of social transfers was to reduce the rate by 2.0 percentage points (to 3.9 %). There were four other regions in Romania – Centru, Nord-Vest, Sud-Est and Sud-Vest Oltenia – where the impact of social transfers led to a relatively small reduction in the risk of poverty (2.8–3.1 percentage points). There were six other regions where the redistributive impact of social transfers led to a reduction that was no greater than 3.1 percentage points:

- the Italian regions of Valle d’Aosta/Vallée d’Aoste and Emilia-Romagna;

- the Greek regions of Voreio Aigaio and Dytiki Makedonia;

- the Croatian regions of Grad Zagreb and Sjeverna Hrvatska.

(%, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_li10_r), (ilc_li41), (ilc_li10) and (ilc_li02)

Material and social deprivation

Material and social deprivation refers to the enforced inability (rather than the choice not to do so) for people to afford five (or more) of the following items: to face unexpected expenses; to pay for one week annual holiday away from home; to pay rent, mortgage/house loan or utility bills; to eat meat, fish or an equivalent source of proteins every second day; to keep a home adequately warm; a car/van for personal use; to replace worn-out furniture; to replace worn-out clothes; at least two pairs of properly fitting shoes; to spend a small amount of money each week on themselves; to participate in a leisure activity; to get together with friends or family for a drink or meal at least once a month; an internet connection.

Note that the material and social deprivation rate is not one of the components used to compute the number/share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion for the EU 2030 target on poverty and social exclusion. For that purpose, the severe material and social deprivation rate is used. It provides information on people experiencing an enforced lack of necessary and desirable items to lead an adequate life (individuals who cannot afford a certain good, service or social activity). It is defined as the proportion of the population experiencing an enforced lack of at least 7 out of 13 deprivation items (six related to the individual and seven related to the household). Regional data for the severe material and social deprivation rate should, in principle, be available for the next edition of the Eurostat regional yearbook.

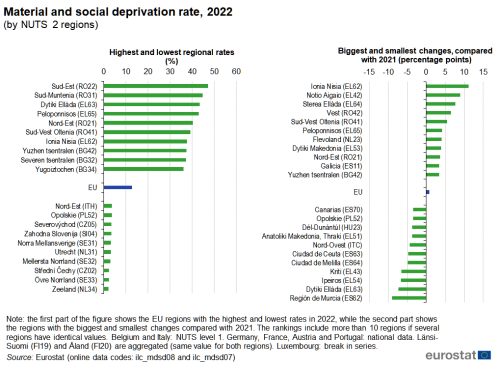

In 2022, the share of people facing material and social deprivation in the EU stood at 12.7 %. This figure was 0.8 percentage points higher than a year before, which may be linked – at least to some degree – to the onset of the cost-of-living crisis.

There were five regions in the EU where more than two fifths of the population experienced material and social deprivation: three were located in Romania and the other two in Greece

Figure 3 shows the regional distribution of material and social deprivation rates. Note that the statistics presented in this section for Belgium, Italy and Serbia relate to level 1 regions and that only national data are available for Germany, France, Austria, Portugal and Türkiye. Generally, material and social deprivation rates tended to be higher in the south-eastern part of the EU, whereas regions in the Nordic Member States had some of the lowest rates.

In 2022, the highest regional shares of people experiencing material and social deprivation were recorded in Sud-Est in Romania (47.1 %). There were four other regions in the EU where more than two fifths of the population were unable to afford at least five of the material and social deprivation items: Sud-Muntenia and Nord-Est (both in Romania); Dytiki Elláda and Peloponnisos (both in Greece). There were a further 12 regions across the EU where the share of people experiencing material and social deprivation was higher than 30.0 %: they were concentrated in southern and eastern EU Member States, with four regions in each of Bulgaria and Greece, three regions in Romania, and a single region from Spain.

At the other end of the distribution, every region in the Nordic Member States, Czechia, Estonia, Croatia, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland and Slovenia had a material and social deprivation rate that was less than the EU average of 12.7 % in 2022; this was also the case in Germany, Austria and Portugal (for which only national data are available). There were four regions in the EU where the material and social deprivation rate was less than 3.0 %: Mellersta Norrland and Övre Norrland (both in Sweden), Střední Čechy (Czechia) and Zeeland (in the Netherlands). Zeeland recorded the lowest material and social deprivation rate in the EU, at 2.1 %.

Greece, Spain, Romania and Hungary were characterised by considerable inter-regional differences in material and social deprivation rates. The range between the highest and lowest regional rates in each of these EU Member States was greater than 20.0 percentage points. The largest range was recorded in Greece (23.4 points), with its highest material and social deprivation rate observed in Dytiki Elláda and its lowest in Ipeiros. By contrast, there were six Member States where inter-regional differences were less than 5.0 percentage points: this was the case in Sweden, Ireland, Denmark, Lithuania, Slovenia and Finland. The latter recorded the smallest range (1.7 points), with its highest material and social deprivation rate observed in Helsinki-Uusimaa and its lowest in Pohjois- ja Itä-Suomi.

(%, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdsd08) and (ilc_mdsd07)

The EU’s material and social deprivation rate was 0.8 percentage points higher in 2022 than in 2021. During this period, the material and social deprivation rate rose in approximately three fifths of regions (80 out of the 141 for which data are available). Among these 80 regions, some of the largest increases in material and social deprivation rates were concentrated in Greece. The biggest was observed in the island region of Ionia Nisia, where the rate increased 11.2 percentage points; it was the only region in the EU to record a double-digit increase. Another popular Greek holiday destination, Notio Aigaio, had the next highest increase (up 9.0 points). There were three more regions in the EU where the material and social deprivation rate increased by at least 5.0 percentage points; this was also the case in the Greek region of Sterea Elláda, and the Romanian regions of Vest and Sud-Vest Oltenia.

The largest decrease recorded across EU regions for the material and social deprivation rate – down 9.0 percentage points between 2021 and 2022 – was reported in the southern Spanish Región de Murcia, where the rate fell from 21.8 % to 12.8 %. The next largest reduction was recorded in the Greek region of Dytiki Elláda (down from 50.6 % to 43.3 %, a reduction of 7.3 points). There were only two other regions across the EU where the material and social deprivation rate fell by at least 5.0 percentage points between 2021 and 2022 – Ipeiros and Kriti (both in Greece).

(by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdsd08) and (ilc_mdsd07)

Income distribution

Gross domestic product (GDP) per inhabitant has traditionally been used to assess regional divergence/convergence in overall living standards. As well as not accounting for income paid/received across borders, it does not capture the distribution of income within a population and thereby does little to reflect economic inequalities. The unequal distribution of income/wealth has gained increasing importance in political and socioeconomic discourse since the global financial and economic crisis and is also a key issue when analysing regions that have been ‘left behind’, or the impact of the cost-of-living-crisis. Note that for statistics on income, the reference period generally refers to the calendar year before the year in which the survey took place.

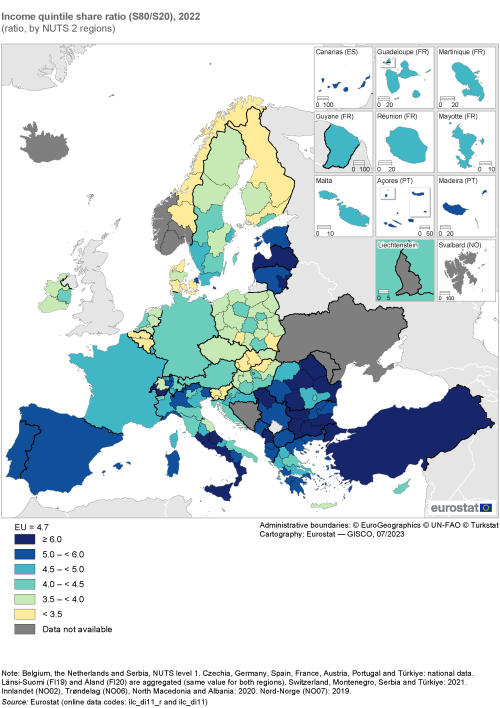

The income quintile share ratio (S80/S20 ratio) measures the inequality of income distribution. It is calculated as the ratio between the share of income received by the 20 % of the population with the highest income (the top quintile) and the share of income received by the 20 % of the population with the lowest income (the bottom quintile). High values for this ratio suggest that there are considerable disparities in the distribution of income between upper and lower income groups. In 2022, the EU’s ratio was 4.7 – in other words, the collective income received by the 20 % of people with the highest incomes was 4.7 times as high as the collective income received by the 20 % with the lowest incomes.

Map 2 shows the regional distribution of the income quintile share ratio. Note that the statistics presented for Belgium, the Netherlands and Serbia relate to level 1 regions and that only national data are available for Czechia, Germany, Spain, France, Austria, Portugal and Türkiye. In 2022, the regional distribution of the income quintile share ratio was skewed: almost two thirds (78 out of 124) of those regions for which data are available had a ratio that was below the EU average; there were two regions that had the same ratio, while just over one third (44 regions) had income disparities that were greater than the EU average.

The highest income quintile share ratio was recorded in the Romanian region of Sud-Vest Oltenia

Across the whole of the EU, the highest income quintile share ratios in 2022 were concentrated in Bulgaria, Italy, Romania and the Baltic Member States. A peak was recorded in the Romanian region of Sud-Vest Oltenia, where the income of the top 20 % of earners was 9.6 times as high as the income of the bottom 20 % of earners. The next highest ratios were observed in two regions of Bulgaria – Severozapaden (8.2) and the capital region of Yugozapaden (7.9) – followed by the southern Italian region of Calabria (7.5).

At the other end of the range, the distribution of income was most equitable in three different regional clusters: in 2022, there was a group of regions that spanned several of the eastern EU Member States, a group in the Nordic Member States, and two out of the three NUTS level 1 regions of Belgium (the exception being the capital region). The income shares held by the highest earning 20 % of the population in the Slovak regions of Bratislavský kraj, Stredné Slovensko and Západné Slovensko were 2.7–3.0 times as high as those held by the lowest earning 20 % of the population; these were the lowest income quintile share ratios across the EU.

Within multi-regional EU Member States, the distribution of income often followed a different pattern in the capital region when compared with the rest of each territory. In 2022, it was commonplace to find that the capital region had the highest income quintile share ratio. This was the case in Belgium (NUTS level 1), Denmark, Ireland, Lithuania, Hungary, Slovenia, Finland and Sweden. By contrast, this pattern was reversed in Romania, as its lowest income quintile share ratio was recorded in the capital region of Bucureşti-Ilfov.

(ratio, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_di11_r) and (ilc_di11)

Consumption expenditure according to the degree of urbanisation

The EU’s annual inflation rate was 9.2 % in 2022. At the time of writing, large numbers of people across the EU are facing significant challenges to maintain their standard of living. The cost-of-living-crisis has resulted from rapid price increases for many types of essential goods and services, in particular, energy and food. The high inflation rate may be linked to a number of factors, including (among others) disruptions to supply chains and logistical issues during the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of Russian military aggression against Ukraine, and a surge in post-pandemic demand. Many people have seen price increases outpace their income growth (in other words, they have become worse-off in real terms). High interest rates, particularly for borrowers, have also heightened the cost-of-living crisis. As a result, the crisis has sparked debate on issues such as income inequality (see above), social welfare and social justice (how to create a fairer and more inclusive society).

Household budget surveys (HBS) are used to collect data on consumption expenditure. The latest data concern 2020 and are therefore likely to have been impacted by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, the crisis led to widespread economic disruptions and changes in consumer behaviour and household spending/saving (linked, at least in part, to restrictions that forced most people to stay at home). With lockdowns and other forms of restrictions in place, many households reduced their spending on non-essential items (like travel, entertainment or luxury goods) and – with considerable uncertainty about their financial future – some increased their precautionary savings. HBS data are analysed according to the classification of individual consumption by purpose (COICOP) and are presented according to the degree of urbanisation. The latter classifies local administrative units based on a combination of geographical contiguity and population density to identify cities, towns and suburbs and rural areas.

Figure 5 shows information on the structure of household consumption expenditure for four specific items that have been the closely scrutinised during the cost-of-living crisis: food and non-alcoholic beverages; electricity, gas and other fuels; the operation of personal transport equipment; and catering services. Note that the data shown relate to the overall share of each item in total household expenditure; the figures do not relate to the actual level of spending. A summary of the highest and lowest shares for national data in 2020 (no data available for Ireland, Portugal, Finland and Sweden; incomplete data for Romania) is presented below:

- for food and non-alcoholic beverages, the range was from a low of 9.4 % of household consumption expenditure in Luxembourg up to a peak of 27.6 % in Romania;

- for electricity, gas and other fuels, it was from 2.6 % in Luxembourg up to 10.5 % in Slovakia;

- for the operation of personal transport equipment, it was from 4.7 % in Belgium up to 10.4 % in Slovenia;

- for catering services, it was from 2.1 % in Hungary up to 8.2 % in Cyprus.

An analysis by degree of urbanisation reveals that people living in rural areas usually spent a higher proportion of their total household expenditure on ‘essential items’; this may be linked, at least in part, to average incomes being lower in rural compared with urban areas. In 2020, the share of total household expenditure accounted for by food and non-alcoholic beverages was – subject to data availability – generally higher for people living in rural areas than for those living in cities. In several eastern and Baltic Member States, the difference between these two shares was considerable. For example, people living in rural areas of Bulgaria spent, on average, 31.2 % of their total household expenditure on food and non-alcoholic beverages, some 9.8 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for people living in cities (21.4 %). Germany was the only exception, as people living in rural areas spent 11.1 % of their household expenditure on food and non-alcoholic beverages, which was marginally lower than the share for people living in cities (0.2 percentage points less).

A similar pattern was observed for electricity, gas and other fuels and for the operation of personal transport equipment, as people living in rural areas generally spent a higher proportion of their total household expenditure on these items. In 2020, the biggest difference in the structure of expenditure on electricity, gas and other fuel was (once again) recorded in Bulgaria: on average, people living in rural areas spent 13.8 % of their total budget on these items, compared with a 7.1 % share for those living in cities (reflecting, at least in part, differences in average income levels for people living in rural areas and cities). For the operation of personal transport equipment, the situation was similar: the biggest difference in the structure of expenditure was observed in Slovenia, where people living in rural areas spent, on average, 11.7 % on these items, compared with a 7.8 % share for people living in cities. Bulgaria was an exception, insofar as people living in cities devoted a slightly higher share of their total household expenditure to the operation of personal transport equipment than those living in rural areas (5.4 % compared with 5.1 %).

For the final group of items – catering services (restaurants, cafés and canteens) – there was a different pattern. For each of the EU Member States (for which data are available), the share of total household expenditure that was accounted for by catering services was systematically higher for people living in cities than it was for people living in rural areas. For example, city-dwellers living in Luxembourg spent, on average, 6.2 % of their total expenditure on catering services, compared with a 4.1 % share for those living in rural areas. The higher proportion of total expenditure devoted to catering services by people living in cities may be linked to a variety of factors, among which:

- cities typically offer a greater concentration of restaurants and cafés, providing better accessibility and more choice;

- cities tend to attract a younger demographic, with younger people more inclined to go out and socialise, while they may also be more open to exploring a broader range of catering options.

For more statistics broken down by degree of urbanisation, see:

(%, by degree of urbanisation)

Source: Eurostat (hbs_str_t221) and (hbs_str_t226)

Source data for figures and maps

Data sources

Statistics on income and living conditions cover objective and subjective aspects of income, poverty, social exclusion, housing conditions, labour, education and health. They are presented in monetary and non-monetary terms for households and for individuals.

As of reference year 2021, EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) have a new legislative basis – Regulation (EU) No 2019/1700 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 October 2019 establishing a common framework for European statistics relating to persons and households, based on data at individual level collected from samples. This is the first time that data collected and processed in compliance with this new legal basis are presented in the Eurostat regional yearbook.

The reference population for the EU-SILC data collection is all private households and their current members residing in the territory of an EU Member State; persons living in collective households and in institutions are generally excluded. The data presented for the EU aggregate are population-weighted averages of national data.

Household budget surveys (HBS) are used to collect data on consumption expenditure. The statistics presented are for reference year 2020; this is the sixth wave of data collection. The information was collected on a voluntary basis, under a so-called gentleman’s agreement; there is no legal basis. HBS data are collected via national surveys and involve a combination of one or more interviews and diaries maintained by households and/or individuals, generally on a daily basis. The principal focus of the data collection is household expenditure on goods and services, although information is also collected for household characteristics. This is one of the key attributes of HBS, insofar as these additional characteristics allow for deeper analyses of expenditure patterns, based on a range of socioeconomic characteristics. In the future, Regulation (EU) No 2019/1700 will provide a legal basis for the collection of household budget survey data; this is planned for the next wave which concerns reference year 2026.

Indicator definitions

People at risk of poverty or social exclusion

The number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion corresponds to the number of persons who are at risk of poverty and/or facing severe material and social deprivation and/or living in a household with a very low work intensity. As well as being expressed as an absolute number, an indicator can also be compiled as a share of the total population.

In 2021, the calculation of the number/share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion was modified to reflect new EU targets introduced within the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan. One of these targets is for the number of people in the EU who are at risk of poverty or social exclusion to decrease by at least 15 million by 2030 (compared with 2019), with children accounting for at least one third of the overall fall. The EU’s 2030 target on poverty and social exclusion redefined two of the components used to calculate the risk of poverty or social exclusion, extending the measure of:

- deprivation by introducing a new indicator for severe material and social deprivation (defined as people experiencing an enforced lack of at least 7 out of 13 deprivation items);

- quasi-joblessness among people living in households with low work intensity (through the inclusion of adults aged 60–64, who were previously omitted).

Note: both of these revised definitions are used to measure the overall number/share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion for the EU’s 2030 target on poverty and social exclusion. Regional statistics for both components – the severe material and social deprivation rate and the share of people (aged 0–64) living in a household with very low work intensity – should be available for the next edition of the Eurostat regional yearbook.

At-risk-of-poverty rate

The equivalised disposable income is the total income of a household, after tax and other deductions, that is available for spending or saving, divided by the number of household members converted into equalised adults. Household members are ‘equalised’ or made ‘equivalent’ by weighting each person according to their age, using the so-called modified OECD equivalence scale (a weight of 1.0 to the first adult; 0.5 to the second and each subsequent person aged 14 years or more; 0.3 to each child aged under 14).

The at-risk-of-poverty threshold is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income after social transfers.

The at-risk-of-poverty rate before social transfers is calculated as the share of people having an equivalised disposable income before social transfers that is below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold (calculated after social transfers). Pensions, such as old-age and survivors’ (widows’/widowers’) benefits, are counted as income before social transfers and not as social transfers. A comparison of rates before and after social transfers gives some idea as to the impact of social transfers in terms of alleviating the risk of poverty. The at-risk-of-poverty rate after social transfers is one of three components for monitoring progress towards the EU’s 2030 target on poverty and social exclusion.

Note, these relative measures do not provide an indication of wealth or poverty directly, but rather they measure the share of people facing low incomes in comparison with other residents in the same country/region; this does not necessarily imply a low standard of living.

Material and social deprivation rate

The material and social deprivation rate is an indicator in EU-SILC that expresses an inability to afford some items considered by most people to be desirable or even necessary to lead an adequate life. The indicator distinguishes between individuals who cannot afford a certain good or service, and those who do not have this good or service for another reason, for example, because they do not want or do not need it.

The material and social deprivation rate is defined as the share of the population who could not afford at least five items out of the following list:

- to face unexpected expenses;

- one week annual holiday away from home;

- to pay rent, mortgage/house loan or utility bills;

- to eat meat, fish or an equivalent source of proteins every second day;

- to keep a home adequately warm;

- a car/van for personal use;

- to replace worn-out furniture;

- to replace worn-out clothes;

- at least two pairs of properly fitting shoes;

- to spend a small amount of money each week on themselves;

- to participate in a leisure activity;

- to get together with friends/family for a drink/meal at least once a month;

- an internet connection.

Note this indicator is different to the severe material and social deprivation rate which is one of the three components used in the calculation of the revised definition for the EU’s 2030 target on poverty and social exclusion.

Income quintile share ratio (S80/S20)

The income quintile share ratio (S80/S20 ratio) is a measure of the inequality of income distribution. It is calculated as the ratio of total income received by the 20 % of the population with the highest incomes (the top quintile) to that received by the 20 % of the population with the lowest incomes (the bottom quintile). All incomes relate to equivalised disposable incomes (see above for an explanation). Note that for statistics on income, the reference period generally refers to the calendar year before the year in which the survey took place.

Structure of consumption expenditure

Data for consumption expenditure are analysed by category using an EU version of the classification of individual consumption by purpose (COICOP). The data are presented in national currency, euro (€) and purchasing power standard (PPS) terms. Data collection only takes place sporadically (not on an annual basis): the information presented here concerns reference year 2020. The next reference year will be 2026.

The main COICOP divisions include: food and non-alcoholic beverages (CP01); alcoholic beverages, tobacco and narcotics (CP02); clothing and footwear (CP03); housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels (CP04); furnishings, household equipment and routine maintenance of the house (CP05); health (CP06); transport (CP07); communications (CP08); recreation and culture (CP09); education (CP10); restaurants and hotels (CP11); miscellaneous goods and services (CP12).

For 2020, HBS data concerning France, Cyprus and Malta were produced by converting 2015 data to 2020 prices using coefficients for harmonised indices of consumer prices.

Note that consumption expenditure data are not collected for life insurance and financial intermediation services indirectly measured. Note also that information on consumption expenditure linked to activities that might be considered as less acceptable by society (for example, the consumption of alcoholic beverages, narcotics or prostitution) are normally under-reported, and hence these figures may not be fully reliable. Such under-reporting may lower the value of overall expenditure, while increasing the relative weight of other expenditure categories.

Context

The COVID-19 crisis had a direct and indirect impact on vulnerable groups such as the elderly, young people, parents of pre-school and school age children (particularly single-parents), low-wage earners, women, migrants, people with disabilities, people with precarious work contracts and those living in areas with limited or no digital connectivity. Some of these groups faced a higher risk of income loss due to increasing unemployment and reduced possibilities for teleworking, while disruptions to services (especially for health and education) may also have exacerbated existing inequalities.

Aside from putting huge pressure on health care services, the crisis also led to considerable demands for additional support from social and welfare services. There was an extensive political debate over how best to respond to the socioeconomic crisis resulting from the pandemic. This reflected, among other issues, the balance between concerns over public finances and the need for further spending on healthcare, education and social protection.

The EU and the EU Member States operate an open method of coordination for social protection and social inclusion. This aims to promote social cohesion and equality through adequate, accessible and financially sustainable social protection systems and social inclusion policies. As such, the EU provides a framework for national strategy development, as well as the opportunity to discuss and learn from best practices and to coordinate policies between EU Member States in areas such as: building a fairer and more inclusive EU, social protection and social inclusion, and pensions.

At the start of March 2021, the European Commission outlined its ambition for an EU that focuses on education, skills and jobs for the future and targets a fair, inclusive and resilient socioeconomic recovery. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan outlines a range of actions designed to promote social rights through the active involvement of social partners and civil society. It also proposes employment, skills and social protection headline targets for the EU. One of the headline targets relates specifically to living conditions, namely that the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion should decrease by at least 15 million persons (of which, at least five million should be children) between 2019 and 2030.

The Action Plan highlights how the principles of the social pillar might be implemented, with the aim of building a stronger social Europe by 2030, through:

- more and better jobs (creating job opportunities in the real economy; making work standards fit for the future of work; improving occupational safety and health standards; increasing labour mobility);

- skills and equality (investing in skills and education to unlock new opportunities for all; building a Union of equality);

- social protection and inclusion (living in dignity; fostering social inclusion and combatting poverty; promoting health and ensuring care; improving social protection).

Under the heading of fostering social inclusion and combatting poverty, the EU plans actions to:

- break intergenerational cycles of disadvantage;

- review the adequacy and coverage of minimum income schemes;

- provide access to affordable housing through raising the quality of the existing housing stock;

- extend access to essential services, such as water, sanitation, healthcare, energy, transport, financial services and digital communications.

Direct access to

- Household budget survey – statistics on consumption expenditure

- Living conditions in Europe – housing

- Living conditions in Europe – material deprivation and economic strain

- Living conditions in Europe – poverty and social exclusion

- Quality of life indicators (online publication)

- Unmet health care needs statistics

News articles

- 13 % of EU children faced material deprivation

- 7 % of EU population unable to keep home warm in 2021

- Ability to make ends meet becoming harder

- Gender gap for income narrower in rural areas

- How many people can afford a proper meal in the EU

- Income inequality across Europe in 2021

- Life satisfaction in the EU slightly down in 2021

- People at risk of poverty: 38 % of income for housing

- People at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2022

- Risk of poverty decreases as work intensity increases

- Housing, food & transport: 61 % of households’ budgets

Online publications

- Regions in Europe – 2023 interactive edition

- Rural Europe – online publication

- Urban Europe – online publication

Statistical publications

- Persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion (EU 2030 target) (t_ilc_pe)

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (t_ilc_ip)

- Living conditions (t_ilc_lv)

- Material deprivation (t_ilc_md)

- Regional poverty and social exclusion statistics (t_reg_ilc)

- Mean consumption expenditure of private households (hbs_exp

- Persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion (EU 2030 target) (ilc_pe)

- Inequality (ilc_iei)

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (ilc_ip)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- Regional poverty and social exclusion statistics (reg_ilc)

Manuals and further methodological information

- Eurostat – methodological publications on income and living conditions

- EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) – Methodological guidelines

- EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) methodology (online publication)

- Household budget surveys – 2020 wave – Description of the data transmission; standardised key social variables: implementation guidelines

- Household budget surveys in the EU - Methodology and recommendations for harmonisation 2003

- Methodological manual on territorial typologies – 2018 edition

- Statistical matching of European Union statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) and the household budget survey

- Statistical regions in the European Union and partner countries – NUTS and statistical regions 2021 – 2020 edition

Metadata

- Consumption expenditure of private households (ESMS metadata file – hbs_esms)

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file – ilc_sieusilc)

- Detailed list of legislative information on EU-SILC provisions for survey design, survey characteristics, data transmission and ad hoc modules

- Regulation (EU) No 2019/1700 – establishing a common framework for European statistics relating to persons and households, based on data at individual level collected from samples – repealing legislation on EU-SILC (as of 01 January 2021)

- European Commission – Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion, see:

- Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2021 – Towards a strong social Europe in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis: reducing disparities and addressing distributional impacts

- Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2022 – Young Europeans: employment and social challenges ahead

- European Platform on Combatting Homelessness

- European Social Fund Plus (ESF+)

- Social protection and social inclusion

- The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan

- European Commission – The European Pillar of Social Rights in 20 principles

Maps can be explored interactively using Eurostat’s statistical atlas (see user manual).

This article forms part of Eurostat’s annual flagship publication, the Eurostat regional yearbook.