Living conditions in Europe - health conditions

Data extracted in December 2020.

No planned article update.

Highlights

In 2019, just over two thirds of the EU population aged 18 years and over perceived themselves as being in good or very good health, while 8.8 % perceived their health status to be bad or very bad.

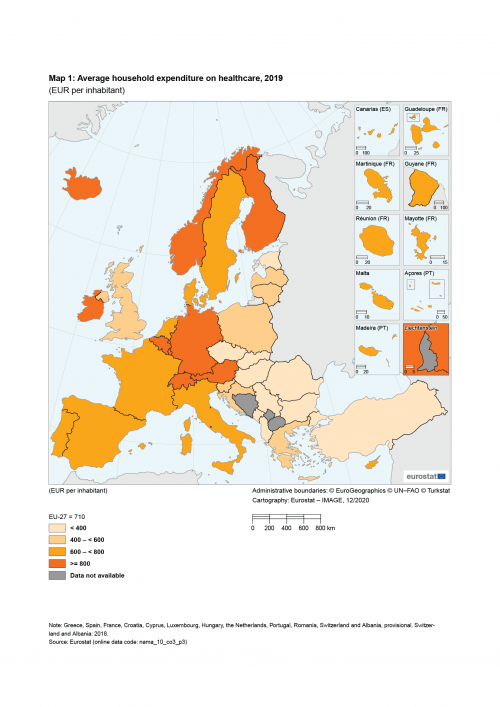

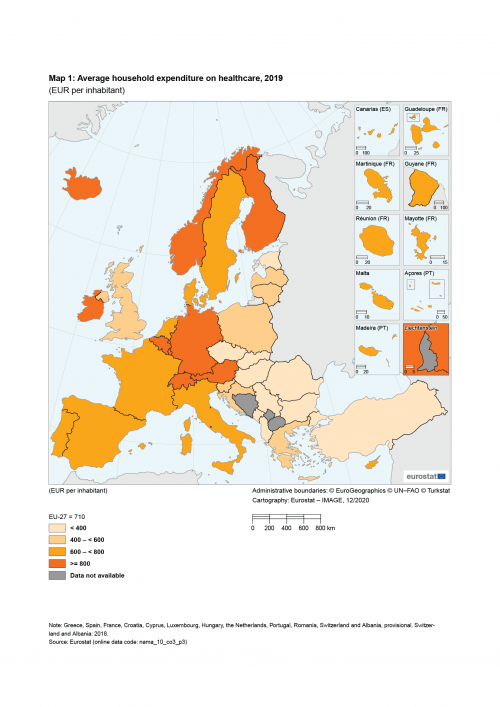

An average of €710 per person was spent on healthcare in 2019 by the EU population, ranging from €250 per person or less in Czechia and Slovakia to €1 000 per person or more in Ireland, Finland, Luxembourg, Germany and Belgium.

(EUR per inhabitant)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_co3_p3)

This article is part of a set of statistical articles that form Eurostat’s online publication, Living conditions in Europe. Each article helps provide a comprehensive and up-to-date summary of living conditions in Europe, presenting some key results from the European Union’s (EU) statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), which is conducted across EU Member States, as well as the United Kingdom and most of the EFTA and candidate countries.

Full article

Key findings

This article presents statistics related to living conditions experienced by people in the EU. It offers a picture of everyday lives across the EU, focusing on the health status of individuals in the EU-27 and the accessibility they have to healthcare, which may potentially have a profound impact on their living standards.

When asked in 2019, just over two thirds (67.8 %) of the EU-27 population aged 18 years and over responded that their health was good or very good.

Health conditions

The statistics presented in this section are based on an evaluation of self-perceived health. Therefore, readers should bear in mind that cultural and personal differences may have an impact on the results.

Two thirds of the EU-27 population perceived themselves as being in good or very good health

In 2019, 67.8 % of the EU-27 population aged 18 years and over reported that their health status was good or very good. At the other end of the spectrum, almost 1 in 10 (8.8 %) persons perceived their health status as being bad or very bad (see Figure 1).

(% of the population aged 18 years and over)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvhl01)

Between the EU Member States, there was a high degree of variation concerning self-perceived health status:

- in 2019, the share of the population aged 18 years and over that perceived their health to be very good, ranged from 4.6 % in Latvia and less than 10.0 % in Lithuania (low reliability data) and Portugal, up to more than two fifths of the adult population in Ireland, Greece and Cyprus (where a peak of 45.7 % was recorded);

- the share of the population that reported their health status as very bad was below 4.0 % in each of the EU Member States, with the highest shares recorded in Croatia and Portugal (both 3.8 %).

Four fifths of employed persons in the EU-27 perceived themselves as being in good or very good health

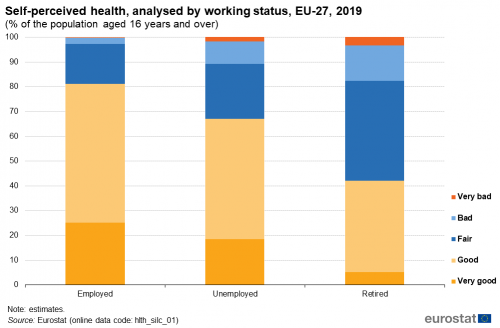

Figure 2 presents an analysis according to working status of the self-perceived health of the EU-27 population in 2019. Among persons aged 16 years and over, some 81.1 % of those in employment reported that they were in good or very good health, compared with just 2.6 % who reported that they were in bad or very bad health.

(% of the population aged 16 years and over)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_01)

The situation was quite different for unemployed persons across the EU-27, as just over two thirds (67.0 %) of this subpopulation perceived their health as being good or very good in 2019, compared with 10.7 % who reported that they were in bad or very bad health.

By contrast, just over two fifths (42.1 %) of retired persons in the EU-27 perceived their health as being good or very good in 2019, compared with 17.7 % who reported that they were in bad or very bad health. Contrary to the other types of working status, the response most often given by retired persons was that they considered their health to be fair (40.2 %).

Perceptions of bad or very bad health status were more prevalent among the elderly, particularly older women

As may be expected — given that many health problems tend to be more common among the elderly — there was a clear relationship between a person’s age and their (perceived) health status (see Table 1).

(% of the specified age group)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_01)

Across the EU-27, 1.4 % of persons aged 16-24 years reported that their health status was bad or very bad in 2019. This share was higher among older age groups, reaching 13.3 % among people aged 65-74 years, 22.5 % among those aged 75-84 years and 34.4 % among those aged 85 years and over. Note that these statistics exclude persons residing in homes for the elderly, where the prevalence of bad or very bad health status is likely to be higher than among the elderly who are living independently. This pattern of a higher share of elderly people (rather than younger people) with bad and very bad health status was repeated in the vast majority of EU Member States.

A more detailed analysis of the situation for persons aged 65 years and over is provided in Figure 3. It shows that in 2019 there was a gender gap, insofar as just over one fifth (20.6 %) of elderly women in the EU-27 perceived their health status as bad or very bad, while the corresponding share among men was 4.2 percentage points lower at 16.4 %.

(% of the population aged 65 years and over)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_01)

The same pattern — a higher share of elderly women (than elderly men) reporting bad or very bad health status — was repeated in 2019 in most of the EU Member States, the only exceptions being Slovenia, France and Finland, where the situation was reversed. This gender gap may, at least in part, be explained by women having a higher level of life expectancy, which may be linked to increased risks for contracting various illnesses/diseases and therefore a deterioration of health status.

The smallest differences between the sexes were recorded in Sweden, Ireland, Slovenia and France: these were the only EU Member States where the gender gap was less than 1.0 percentage points. By contrast, the gap between the sexes in 2019 was 11.1 percentage points in Portugal and 12.4 percentage points in Lithuania.

In 2019, the share of elderly women that reported bad or very bad health status was more than two fifths in Croatia, Portugal and Lithuania. Croatia also recorded the highest share of elderly men reporting that they had bad or very bad health status (36.8 %), followed by Slovakia (34.0 %).

High costs proved to be a barrier to accessing medical care and dental care for 0.9 % and 2.5 % of the EU-27 population

The provision of free state-funded medical examinations and treatments varies considerably between EU Member States, reflecting the different organisation of health services and the balance between public and private provisions. Relatively high medical or dental costs may act as a barrier preventing some individual patients from accessing the healthcare they require.

Across the EU-27, some 0.9 % of the population aged 16 years and over stated in 2019 that the high cost of medical care was the main reason that resulted in them having unmet medical needs (see Table 2). This share varied from less than 1.0 % in 19 EU Member States, up to 2.8 % in Latvia, 3.5 % in Romania and 7.5 % in Greece.

(% of the population aged 16 years and over)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_silc_08) and (hlth_silc_09)

Among the first income quintile (in other words, the 20 % of the EU-27 population with the lowest incomes), the share of adults with unmet medical needs due primarily to their cost/expense was 2.1%. By contrast, among the 20 % of highest-earners in the EU-27 (the top or fifth income quintile), the share of adults who stated that their main reason for unmet medical needs was due to their cost/expense was much lower (0.1 %). A similar pattern was repeated in 2019 across nearly all of the EU Member States, with a higher proportion of the adult population in the first income quintile (than the fifth income quintile) reporting unmet medical needs primarily because care was too expensive. The only exceptions were Spain and Sweden where the shares were 0.0 % for the first and fifth quintiles. In Greece, the share of the adult population in the lowest income quintile with unmet medical needs in 2019, primarily because care was too expensive, was 16.6 percentage points higher than the corresponding share recorded among the adult population in the top income quintile; this was the only EU Member State where the gap between the shares for these two subpopulations was in double-digits.

In 2019, the share of the adult population in the first income quintile with unmet medical needs, primarily because care was too expensive peaked at 17.4% in Greece, while Romania (6.3 %) and Latvia (6.1 %) reported that more than 5.0 % of this subpopulation had such unmet needs. By contrast, there were 12 EU Member States where less than 1.0 % of the adult population in the first income quintile reported that the principal reason why they had unmet medical needs was because care was too expensive.

A similar analysis for the top income quintile in 2019 reveals that Greece also had the highest share (0.8 %) of this subpopulation with unmet medical needs because care was too expensive; Romania (0.7 %) was the only other EU Member State where more than 0.5 % of the top income quintile reported unmet medical needs due to such care being too expensive. By contrast, 0.0 % of the adults in the top income quintile reported unmet medical needs primarily because care was too expensive in 14 Member States.

Although not usually life-threatening, dental conditions may result in excruciating pain, while untreated dental problems may have longer-term detrimental effects on both an individual’s health and well-being.

In 2019, the share of the EU-27 population aged 16 years and over reporting that the high cost/expense of dental care had resulted in unmet dental care needs was 2.5 % — about 2.8 times the corresponding share for unmet medical needs due to reasons of expense. This may reflect some people giving a higher priority to their medical needs rather than their dental needs and may also be affected by the relatively high level of dental care costs in some EU Member States, in comparison to medical costs which are often (entirely) paid for / reimbursed by social security systems.

The share of the population with unmet dental needs primarily due to the cost/expense of treatment ranged from less than 1.0 % in nine EU Member States (with the lowest share being 0.2 %, recorded in Malta) to 8.6 % in Greece, 9.6 % in Portugal and 9.8 % in Latvia.

Some 5.5 % of the EU-27’s adult population in the lowest income quintile had unmet dental needs in 2019 due to the cost/expense of treatment, compared with 0.6 % of the EU-27 adult population in the top income quintile. Across the EU Member States, people in the bottom income quintile were considerably more likely to have unmet dental needs than their fellow residents in the uppermost income quintile. In Germany, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Sweden, 0.0 % of the adult population in the uppermost (fifth) income quintile had unmet dental needs.

Large differences in the amount of money households spent on healthcare

National accounts provide information about household consumption expenditure on goods and services. This information may be analysed according to the classification of individual consumption by purpose (COICOP). Division 06 of this classification covers health, including expenditure on: medical products, appliances and equipment; outpatient services; hospital services.

On average, €710 were spent on health per inhabitant in the EU-27 in 2019 (see Map 1). There were large differences in the level of expenditure in 2019 between EU Member States, from lows in Slovakia (€230 per inhabitant) and Czechia (€250 per inhabitant) up to €1 000 or more per inhabitant in Ireland, Finland, Luxembourg, Germany and Belgium (where the highest value was recorded, averaging €1 350 per inhabitant).

These variations reflect, to some degree, the different provisions for the delivery of healthcare across the EU Member States: on the one hand, there are some characterised by predominantly public systems financed through taxation, where healthcare is provided free at the point of use; others are characterised by social premium payments, whereby patients usually pay their medical bills and are later reimbursed by government. In the Member States where healthcare provision tends to be provided free at the point of use, it is more commonplace to find that expenditure per inhabitant on health was relatively low.

(EUR per inhabitant)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_co3_p3)

A more detailed analysis for the EU-27 reveals that expenditure on health in 2019 was concentrated on medical products, appliances and equipment (43.0 %) and out-patient services (39.4 %), while a relatively small share (17.6 %) was accounted for by hospital services (see Figure 4).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_co3_p3)

Source data for tables and figures

Data sources

The data used in this article are primarily derived from EU-SILC. EU-SILC data are compiled annually and are the main source of statistics that measure income and living conditions in Europe; it is also the main source of information used to link different aspects relating to the quality of life of households and individuals.

The reference population for the information presented in this article is all private households and their current members residing in the territory of an EU Member State (or non-member country) at the time of data collection; persons living in collective households and in institutions are generally excluded from the target population. The data for the EU are population-weighted averages of national data.

At the end of the article data are presented from national accounts; this set of information relates to household consumption expenditure statistics.

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value. |

Context

Universal access to good healthcare, at an affordable cost to both individuals and society at large, is widely regarded within the EU as a basic need. Equally, good health is widely regarded as a major determinant for an individual’s quality of life and their ability to participate in social and family-related activities, while at the same time promoting economic growth and overall well-being.

Direct access to

- EU-SILC ad-hoc modules (ilc_ahm)

- 2018 and 2013 - Personal well-being indicators (ilc_pwb)

- Health, see:

- Health status (hlth_state)

- Health care (hlth_care)

- Detailed breakdowns of main GDP aggregates (by industry and consumption purpose) (nama_10_dbr)

- Final consumption expenditure of households by consumption purpose (COICOP 3 digit) (nama_10_co3_p3)

- Annual national accounts (ESMS metadata file — nama10_esms)

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

- Income and living conditions — information on data

- Income and living conditions — methodology

- 2018 and 2013 personal well-being indicators (ESMS metadata file — ilc_pwb_esms)

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion — Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2020

- European Commission — Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion — Indicators’ Sub-Group of the Social Protection Committee

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety — Public health

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety — State of health in the EU

- OECD — Health at a glance

- World Health Organization