Early estimates of income inequalities

Data extracted in July 2023

Planned article update: 17 July 2024

Highlights

Early estimates show that the at-risk-of-poverty rate remained stable, while disposable income in nominal terms increased in all EU countries.

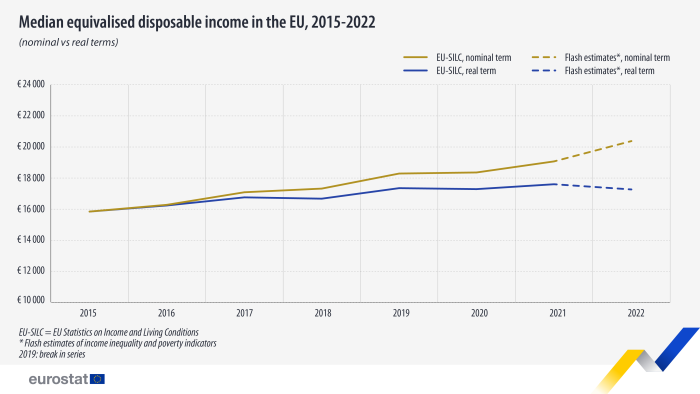

Early estimates show that the EU median disposable household income decreased by about 2% in real terms, while in nominal terms it increased by about 7%.

The at-risk-of-poverty rate adjusted by the price evolution in 2022 signals a deterioration of living standards in several countries.

This article presents early estimates of income inequality and poverty indicators for 2022, produced by Eurostat as experimental statistics based on microsimulation and nowcasting techniques. All figures refer to the annual change for income based indicators from 2021 to 2022 and complement the official 2021 income data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) collected in 2022[1]. Therefore, early estimates aim to give preliminary information on the evolution until the corresponding income data from EU-SILC becomes available (2024). The methodology takes into account both the effect of the labour market evolution on employment income and the changes in social protection schemes put in place by national governments. For the latter, Eurostat uses the EUROMOD microsimulation model[2], which provides the effects of direct taxes, social security contributions and benefits on households’ income. Additional information on specific material deprivation items from EU-SILC 2022 complement the analysis.

Full article

Key findings

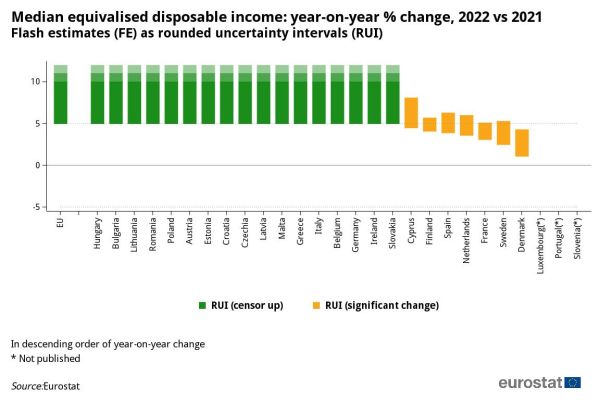

Early estimates for 2022 show a significant overall increase of 6.8 % in median equivalised disposable income at EU level, with positive changes estimated for all countries. The increase in disposable income is sustained by the positive evolution of the labour market and by several income support measures put in place to mitigate the impact of inflation, in particular to help low-income households. Therefore, the at-risk-of-poverty rate is estimated to remain stable at EU level (-0.2 percentage points, pp). It should be noted that these indicators are based on nominal values of disposable income and therefore do not incorporate changes in the cost of living and purchasing power.

Despite high nominal increases, the nowcasted median disposable income will decrease in real terms in most EU countries. Rising prices for essential items (goods and services)[3], such as food, energy and transport were the main reason for the decrease of the real income. At EU level, the prices of essential items rose by 16.8 % from 2021 to 2022.

It is estimated that inflation led to a 1.9 % decrease for EU median disposable income in real terms in 2022 (compared to 2021). The effect of inflation is likely stronger for low-income households, as essential items represent a higher share of their overall consumption, and they have little margin for adjusting their consumption. In this context, the at-risk-of-poverty rate anchored in 2021[4] can complement the standard poverty indicator as it partially captures the evolution in the cost of living. This is estimated to statistically significant increase for about half of the EU countries. Complementary information from EU-SILC also shows a +2.4 pp increase in 2022 in the share of households declaring they were unable to keep a house adequately warm.

The uncertainty of the early estimates is particularly high for recent years due to significant fluctuations in the labour market, as well as due to temporary measures put in place by governments to alleviate the economic hardships the COVID-19 pandemic and the current inflation crisis have brought to households. A number of caveats and assumptions[5] should therefore be considered when interpreting the early estimates. The early estimates at country level throughout this article are presented as rounded uncertainty intervals (RUI), which accounts for the fact that the expected changes cover a possible range of values associated with uncertainty. Not showing the point estimate is intended to minimise the risk of misinterpretation as a result of disregarding the uncertainty of the estimate.

The standard nowcasting methodology for the early estimates of income and poverty takes into account income support measures introduced to shield consumers from rising and volatile energy prices[6]: e.g., indexation of wages, allowances, energy bonuses or specific social assistance benefits often intended to sustain vulnerable population sub-groups. However, the methodology does not cover indirect taxes or household expenditures and do not capture the effects of a complete range of price related measures, such as VAT changes, social tariffs, price caps and the like. For more details, see the methodological note.

Median disposable income is nowcasted to increase significantly at EU level and across all countries

Figure 1 presents the expected evolution of the median disposable income in nominal terms by EU country. In all countries for which data is published, a statistically significant increase in median disposable income is estimated for 2022 compared with 2021. For the EU as a whole, an increase of 6.8 % of median disposable income in 2022 is nowcasted, with 17 countries registering increases higher than 5 % (in green).

Explanatory note: Extreme values, where the uncertainty interval is entirely above a certain threshold, are censored, and an open-ended interval bounded by the limit is shown in green instead of the rounded uncertainty interval (RUI), conveying the message that the changes are relatively large. The lower limit for what is considered an extreme value is 5 % for deciles. For more details, see the general report on flash estimates 2022, Section 5: Communicating the FE: magnitude and direction of change using rounded uncertainty interval dissemination format.

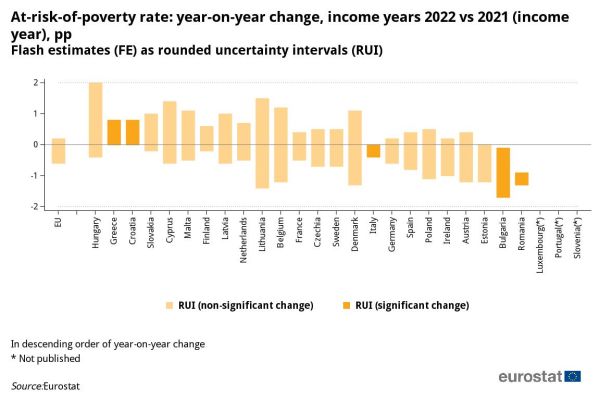

At-risk-of-poverty rate estimated to decrease or remain stable for most countries

Figure 2 shows the estimated change of the at-risk-of-poverty rate based on 2022 income data (nowcasting EU-SILC 2023). At the aggregate EU level, income poverty is estimated to remain stable. In the current context, it is important to note that the indicator does not take into account households’ expenditure and cost of living.

At country level, Figure 2 shows (in dark yellow) a statistically significant increase for two EU countries (Greece and Croatia). Most countries showed stability or not significant changes, while a statistically significant decrease (in dark yellow) was estimated for Italy, Bulgaria and Romania.

Improvements in employment income sustain the overall estimated growth in disposable income

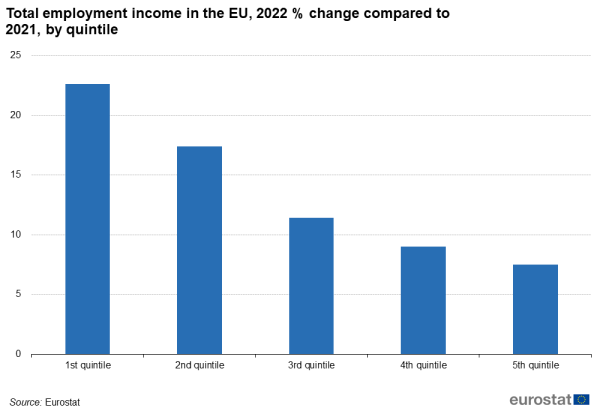

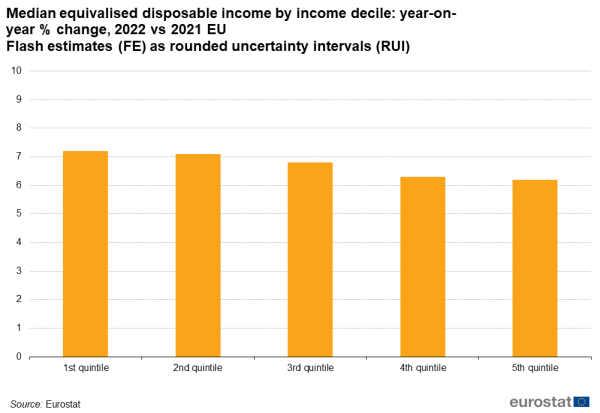

Estimated increases in disposable income were sustained by the positive evolution of employment income[7] across income quintiles[8]. Early estimates show higher increases for workers with lower earnings. This is in line with the positive evolution of the labour market: the return to work of workers affected by COVID-19 measures and indexation measures for wages across EU countries.

Figure 4 illustrates the evolution of equivalised disposable income by quintile, comparing 2022 to 2021. Besides earnings from employment, disposable income refers to a household’s total income including taxes and social benefits

High inflation had a negative impact on households’ income in real terms

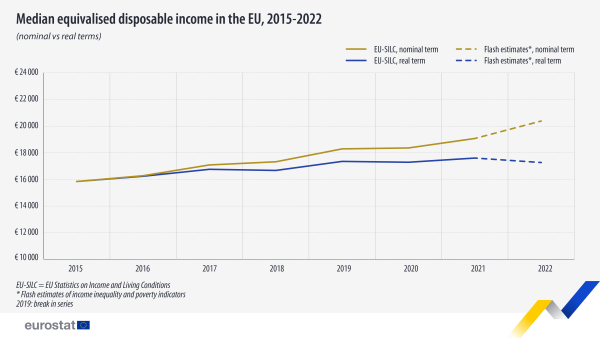

Early estimates of the median disposable income in 2022 in the EU showed a 6.8% (Figure 5) increase in nominal terms. In the context of the current inflation crisis, it is also important to monitor the evolution of disposable income in real terms. This makes it possible to take into account not only the changes in households’ income, but also to estimate the impact of the rising cost of living.

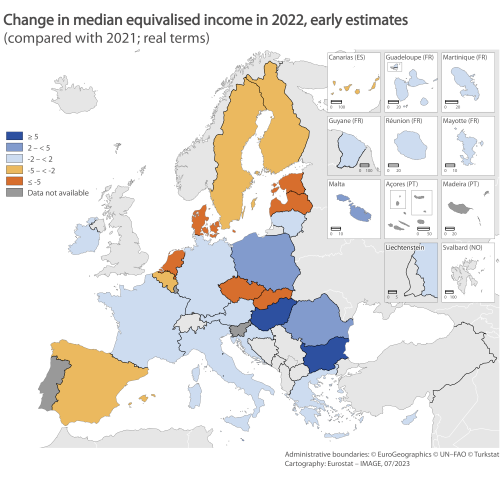

The overall inflation at EU level reached 9.2 % in 2022. In the context of poverty and income distribution, it is important to highlight that essential items, such as food, energy and transport, registered much higher increases. In the EU, median disposable income decreased in real terms by 1.9 % between 2021 and 2022, with negative values in most countries (Figure 5). This inflation-adjusted measure of disposable income is calculated using the overall harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP).

Figure 6 shows the change in median disposable income in real terms at country level. The largest decreases were estimated in Estonia, Latvia, the Netherlands, Denmark, Slovakia and Czechia. It increased most sharply in Hungary and Bulgaria.

Support measures to cope with rising inflation and the cost of living

In the standard methodology for early estimates produced by Eurostat policies and income support measures for households are simulated via the tax-benefit model (EUROMOD). These include for 2022 indexation measures, social assistance benefits, housing benefits and allowances often intended to sustain vulnerable population sub-groups/low-income households. Examples range from the universal climate bonus (e.g., Austria), compensation measures to households to cope with high energy prices (e.g., Germany, France, Slovenia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Italy and Netherlands), a temporary increase in the national minimum income benefit and/or minimum living standard (e.g., Spain, Czechia and Greece). More information on the specific energy measures simulated in EUROMOD in different countries can be found in the EUROMOD Country Reports. However, standard income and poverty indicators in nominal terms do not account for the evolution in the cost of living[9]. Inflation adjusted indicators, such as median income in real terms or the anchored at-risk-of-poverty rate reflect, at least partly, the impact of rising energy prices and related compensation measures (e.g., VAT cuts, social tariffs and price caps). Further details on the treatment of energy price compensation measures in the HICP can be found here.

Inflation more likely to affect the material wellbeing of low-income households

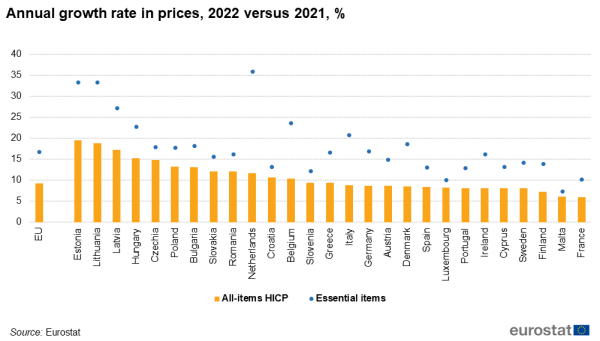

The median disposable income in real terms gives a first indication of the impact of inflation on households’ material wellbeing. However, the HICP measures the change over time in the prices of consumer goods and services as an average across all households. To assess the asymmetrical effects of inflation along the income distribution it is relevant to consider both the commodity groups most impacted by high inflation and the structure of expenditure of different household groups.

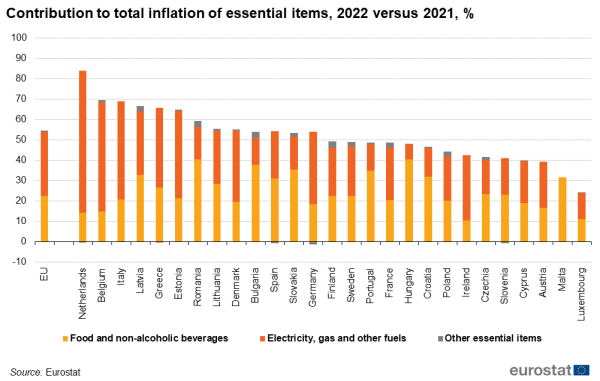

Figure 7 provides the annual rate of change in 2022 of the overall HICP and a specific index that reflects the overall increase in selected product categories considered as essential items. This latter index registered in 2022 an annual rate of change of 16.8 % at EU level with the largest increases (>30 %) in the Netherlands, Lithuania and Estonia, and the lowest (<11 %) in France, Luxembourg and Malta.

Figure 8 shows that essential items contributed to price increases in 2022 with more than 50 % of total inflation. Within the essential items, the biggest contributors to inflation were ‘Electricity, gas and other fuels’ and ‘Food and non-alcoholic beverages’ components. The ‘Electricity, gas and other fuels’ item stands out as one of the key factors behind the increase in the price index. For example, in the Netherlands, ‘Electricity, gas and other fuels’ was the biggest contributor to price increases in 2022, with almost 70 % contribution to the overall price change. This was also the case for Italy, Belgium and Estonia, where it contributed for more than 40 % of the total HICP. On the other hand, the ‘Food and non-alcoholic beverages’ stood out (>30 % of the contribution to total inflation) in Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Portugal, Croatia, Malta and Spain.

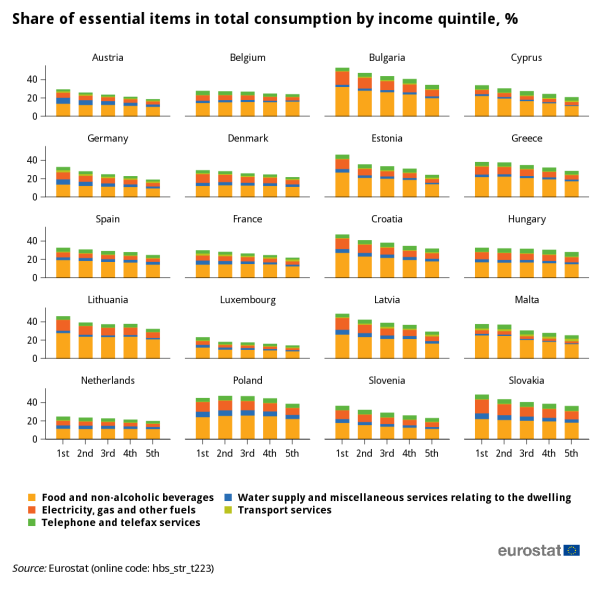

Figure 9 shows the consumption shares of the main essential items across the income quintiles based on the latest Eurostat figures on consumption from 2020 (for 20 countries)[10]. We note that for low-income households, these items represent a higher share of their overall consumption in comparison with the rest of the population. This is a consistent pattern across time and thus likely to increase the strain on low-income households also in 2022.

The higher impact of inflation on low-income households is confirmed by additional indicators that take into account the distributional effects of inflation.

Figure 10 provides the early estimates for the at-risk-of poverty rate, where the poverty threshold is anchored in 2021[11]. In this case, the poverty threshold is calculated based on the 2021 income level adjusted for inflation 2021-2022. The indicator is shows the estimated evolution in the percentage of people under this inflation-adjusted poverty threshold.

For about half the EU countries early estimates show an increase (> 0.5 percentage points; pp) in the anchored at-risk-of-poverty rate, signalling a deterioration of the standard of living for households. This increase is larger (≥ 2 pp) in three countries (Estonia, Latvia, the Netherlands). However, a decrease (< -0.5 pp) is estimated in Austria, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary.

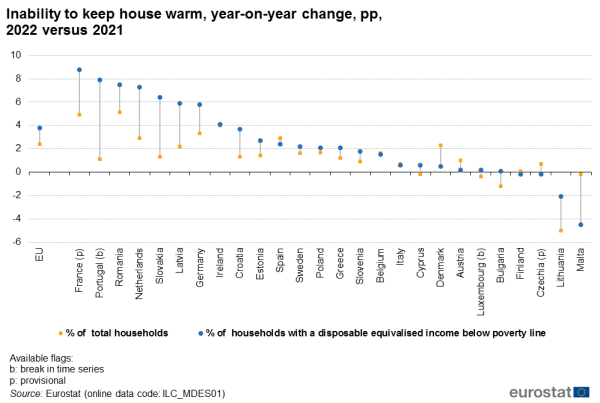

In addition, subjective indicators collected in EU-SILC, such as the inability to keep a house warm provide a good indication of the impact of the energy crisis on the poorest households. Figure 11 shows an increase in most countries for the share of households who declared they were unable to keep their house adequately warm. This increase was higher for households whose equivalised disposable income was below the poverty line. Seven EU countries registered an increase over 5 pp in 2022: France showed the highest increase (+8.8 pp), followed by Portugal (+7.9 pp), Romania (+7.5 pp), the Netherlands (+7.3 pp), Slovakia (+6.4 pp), Germany (+5.8 pp) and Latvia (+5.8 pp).

Feedback

To help Eurostat improve these experimental statistics, users and researchers are kindly invited to give us their feedback by email

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The data used in this report are based on Eurostat estimations. For microsimulation, the information set that was entered includes the EUROMOD[12] microsimulation model combined with the latest EU-SILC users' database (UDB) microdata file and/or national SILC microdata available at the time of production. This is enhanced with the latest information on labour from the reference period (2021) – Labour Force Survey (LFS).

EU-SILC further information

- Income, social inclusion and living conditions

- EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) methodology

EUROMOD, the European Union tax-benefit microsimulation model, originally maintained, developed and managed by the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER) at the University of Essex, since 2021 is maintained, developed and managed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) in the European Commission, in collaboration with EUROSTAT and national teams from the EU Member States.

EU-LFS further information. For more in-depth information on EU Labour Force statistics in 2022 that was used in our estimations please consult the links below:

The part of the article on inflation is based on the HICP, which is an index for measuring the change in prices of consumer goods and services acquired by households in monetary transactions. More information on this topic can be found here:

Price statistics further information:

Context

All figures provided are part of the experimental statistics produced by Eurostat in the context of early estimates on income inequality and poverty indicators. The final income indicators for 2022 from the EU-SILC 2023 will be released in 2024.

Early estimates are based on nowcasting and modelling techniques that take into account the labour market changes and the effects of different policy measures supporting household income in 2022. While the standard nowcasting methodology focuses on nominal data, additional analysis in the article reflects the estimated impact of the inflation in 2022.

Direct access to

Methodology

Indicators on poverty and income inequality are based on EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). In order to provide timelier data on income poverty and distribution Eurostat is producing flash estimates (FE) with a release date appreciably earlier than the survey data These estimates are calculated on the basis of nowcasting and modelling techniques[13].

The standard nowcasting methodology to produce flash estimates on income indicators follows two main steps:

1) The impact of the labour market on income distribution was modelled using detailed and up-to-date distributional information on the employment net changes from the EU-LFS and other national sources. The standard methodology is based either on reweighting or labour transitions at individual level. For flash 2022 annual labour transitions are used. Overall trends in labour market are translated in distributional information by assessing the probabilities to lose/find employment. These are modelled via a logistic regression at individual level based on LFS longitudinal data. Income from work is updated according to changes on the labour market and in line with the general evolution in auxiliary sources which are more up to date.

2) The impact of social policies: government transfers are simulated via EUROMOD, the European Union tax-benefit microsimulation model, managed, maintained and developed by the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER) at the University of Essex and the Joint Research Centre (JRC) in the European Commission, in collaboration with national teams from the EU Member States. Income elements simulated by the model include universal and targeted cash benefits, social insurance contributions and personal direct taxes. Data on income that cannot be simulated mostly concern benefits for which entitlement is based on previous contribution history (e.g. pensions) or unobserved characteristics (e.g. disability benefits). These are extracted from the data and updated according to statutory rules (such as indexation rules) or changes to average levels over time. For the purposes of the flash estimates exercise standard EUROMOD policy simulation routines are enhanced with additional adjustments to the input data to take into account the most recent policy changes in the population structure, the evolution of employment and main indexation factors.

It is important to note in the current context that the standard nowcasting methodology takes into account income support measures introduced to shield consumers from rising and volatile energy prices : e.g., indexation of wages, allowances, energy bonuses or specific social assistance benefits often intended to sustain vulnerable population sub-groups. However, the methodology does not cover indirect taxes or household expenditures and do not capture the effects of a complete range of price related measures, such as VAT changes, social tariffs, price caps and the like. More information on the specific energy measures simulated in EUROMOD in different countries can be found in the EUROMOD Country Reports.

Finally, the uncertainty of the early estimates is particularly high for recent years due to significant fluctuations on the labour market, as well as due to temporary measures put in place by governments to alleviate the economic hardships the COVID-19 pandemic and the current inflation crisis brought to households. A number of caveats and assumptions should therefore be considered when interpreting the early estimates: incomplete information and model errors for the estimation of employment income; over-simulation of benefits related to compensation schemes and assumptions of full take-up of benefits; lack of information on the informal economy and workers who fell outside the safety net of the tax-benefit system.

For more details please see here.

Notes

- ↑ The reference period for most of the information collected in EU-SILC is the data collection year. However, income-based indicators refer to the previous calendar year (fixed 12-month period). For more information, please also see Income and living conditions (ilc) (europa.eu).

- ↑ Social benefits and taxes are simulated via the EUROMOD tax benefit model]. This is maintained, developed and managed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission, in collaboration with Eurostat and national authorities from the EU countries.

- ↑ Essential items, usually considered fundamental for meeting basic needs and maintaining a reasonable standard of living, are defined for the purpose of this exercise by the aggregation of the following COICOPclasses: Food and non-alcoholic beverages (CP01); Water supply (CP0441); Refuse collection (CP0442); Sewerage collection (CP0443); Electricity, gas and other fuels (CP045); Passenger transport by railway (CP0731); Passenger transport by road (CP0732); Combined passenger transport (CP0735); Other purchased transport services (CP0736); Telephone and telefax services (CP0830).

- ↑ People at-risk-of poverty anchored at 2021 are those with an equivalised disposable income below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold calculated in 2021 adjusted with the evolution of HICP between 2021 and2022. The AROP anchored indicator is defined as the percentage of persons in the total population who are under this inflation-adjusted poverty threshold.

- ↑ Incomplete information and model errors for the estimation of employment income; over-simulation of benefits related to compensation schemes and assumptions of full take-up of benefits; lack of information on the informal economy and workers who fell outside the safety net of the tax-benefit system.

- ↑ Some income support measures cannot be simulated in the model due to the lack of data on the energy consumption of households or the amounts compensated.

- ↑ It includes wages and self-employment income

- ↑ Quintiles are based on the ranking of people in terms of their employment income.

- ↑ The EU-SILC definition of income and poverty does not take into account the effect of increasing prices for food, energy, interest rates or other essential items.

- ↑ No detailed data on expenditure is available for 2022 to build specific inflation rates across the different income groups. In addition, it is important to consider that during 2020 consumption patterns were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the higher share of essential items for lower quintiles is a constant pattern across time and thus likely to increase the strain on low-income households also in 2022.

- ↑ The poverty threshold for income 2021 (EU-SILC 2022) is adjusted with the evolution of HICP between 2021-2022. It is intended to nowcast the anchored at-risk-of-poverty rate to be collected in EU-SILC 2023.

- ↑ EUROMOD is a tax-benefit microsimulation model for the EU and UK that enables researchers and policy analysts to calculate, in a comparable manner, the effects of taxes and benefits on household incomes and work incentives for the population of each country and for the EU as a whole. The implementation of policies is coordinated by the Joint Research Centre and national teams

- ↑ For Romania, flash estimates are based on current income information collected in HBS (Household Budget Survey – Romania).