Children in migration - demography and migration

Data extracted in June 2023

Planned article update: in June 2024

Highlights

On 1 January 2022, around 6.6 million children aged less than 18 years did not have the citizenship of their country of residence in the EU.

Despite an increase in 2021 by 23.4 %, the number of non-EU children aged less than 15 years who migrated to one of the EU Member States (271 000) was still lower than the level observed in 2019, before COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2021, 11.5 % of newborns (470 000 births) in the EU had a mother who was not an EU citizen.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

This article presents European statistics on children in migration based on international migration (flows), the number of national and non-national citizens in the population (stocks) as well as data relating to live births by mother's citizenship and the acquisition of citizenship. It focuses mainly on flows and stocks of foreign and stateless children broken down by EU and non-EU citizens. Migration of children depends mainly on the migration of their parents or relatives, even if migration includes unaccompanied minors.

The main explanatory factors of migration can be found in the combination of economic, environmental, political and social factors: either in a migrant's country of origin (push factors) or in the country of destination (pull factors). Historically, the EU's relative economic prosperity and political stability is thought to have exerted a considerable pull effect on migrants. Eurostat data on asylum applicants and managed migration, even if not directly comparable with international migration and population statistics, provide complementary information on children in migration.

For more information see the articles Children in migration – asylum applicants and Children in migration – residence permits for family reasons.

Full article

Total number of non-national children in the EU: main indicators in 2022

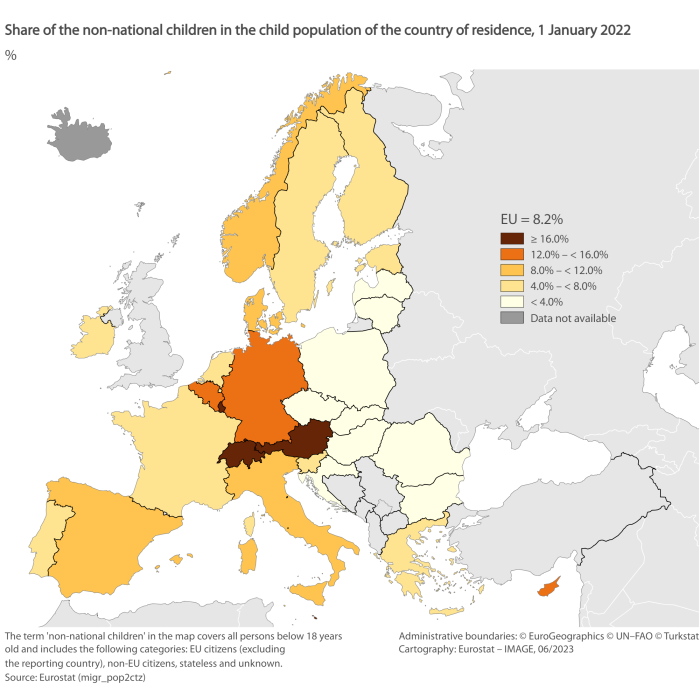

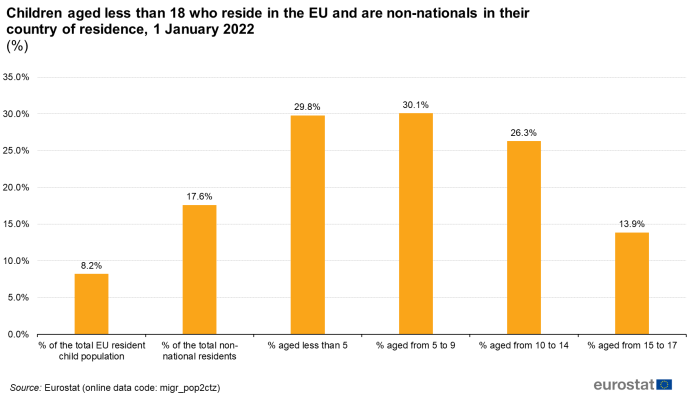

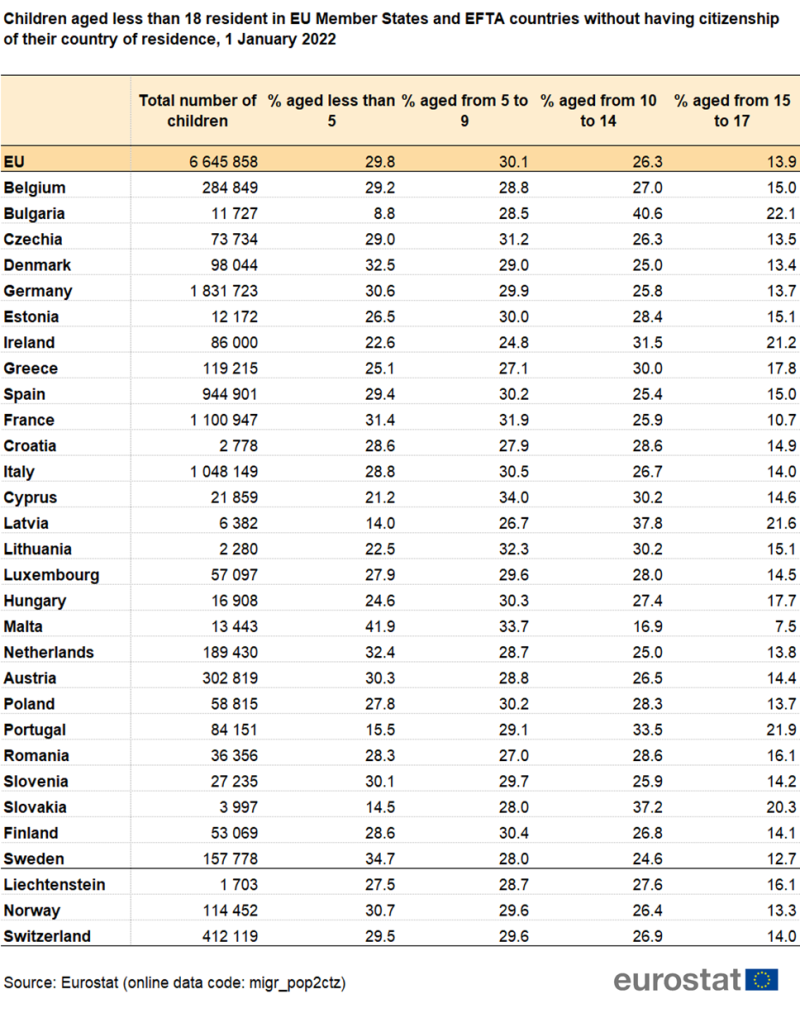

On 1 January 2022, around 6.6 million children aged less than 18 years did not have the citizenship of their country of residence in the EU. It accounted for 8.2 % of the total number of children living in the EU and 17.6 % of the total number of non-national residents. When looking at the distribution by main age groups, their weight is negatively correlated with age, with the highest weights being observed for the 0-4 years and 5-9 years age groups (29.8 % and 30.1 %, respectively). In comparison, the shares of children aged less than 5 years and those aged from 5 to 9 years in the total number of children in the EU amount respectively to 25.7 % and 27.7 %.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

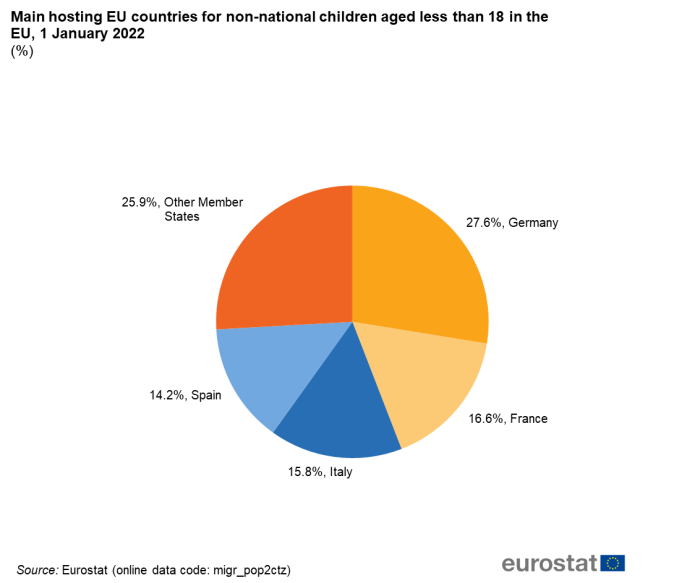

As shown in Figure 2, Germany (27.6 %), France (16.6 %), Italy (15.8 %) and Spain (14.2 %) are the main EU countries hosting non-national children in absolute terms – almost three out of four children without the citizenship of their country of residence were residing in one of those four Member States on 1 January 2022.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

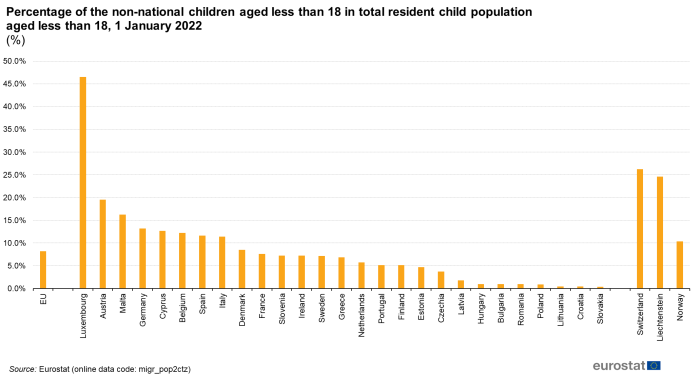

In relative terms, when looking at the share of non-national children in the total child population at country level, the highest shares are observed in Luxembourg (46.6 %), Austria (19.5 %), Malta (16.3 %) and Germany (13.2 %), with this share also higher than 10 % in four other EU Member States (Cyprus, Belgium, Spain, and Italy). In all other Member States, except for Denmark (8.5 %), this share is lower than the EU average, with the lowest shares observed in Romania, Slovakia (each 0.4 %) and Lithuania (0.5 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

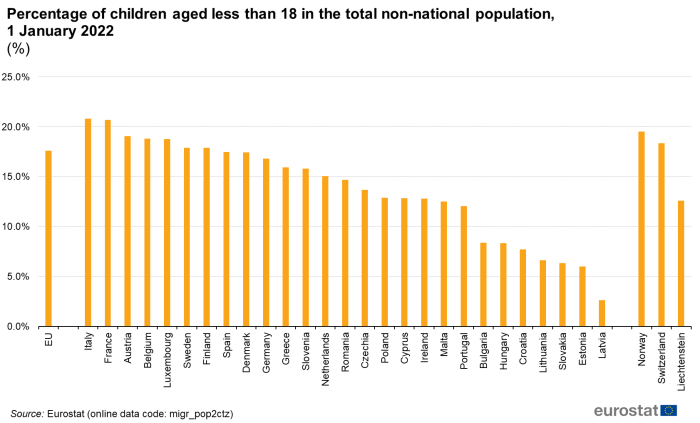

The share of non-national children in the total non-national population in Figure 4 not only depends on past migration flows but also on the number of births of non-national children on the territory of the host country and policies on the acquisition of citizenship. This share is higher than the EU average (17.6 %) in seven Member States, with a value higher than 20 % in Italy (20.8 %) and France (20.7 %), while it is lowest in the Baltic countries and Slovakia.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

Concerning the breakdown by age group, Table 1 shows that it varies from one EU Member State to another. For example, the share of children aged less than 5 years is higher than 40 % in Malta, and lower than 20 % in four Member States (Portugal, Slovakia, Latvia and Bulgaria).

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

Non-national children in the EU: development over 2014-2022

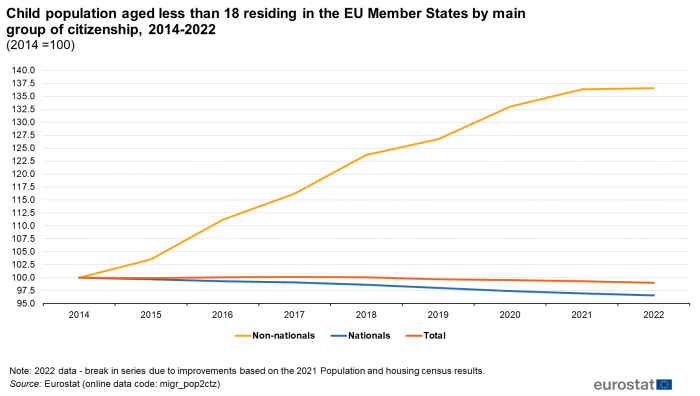

The development of the child population in the EU by main groups of citizenship shows the impact of each group of citizenship on the development of the total child population in the EU. This dynamic, as already stated, is influenced by several factors: emigration and immigration flows, acquisition of citizenship, birth of non-national children, and the fact that each year, some of the children become adults. Figure 5 presents the index trend (2014 = 100) over 2014-2022 for the total child population and the populations of national and non-national children in the EU. It shows that the increase (+36.6 %) of the population of non-national children between 2014 and 2022 almost compensated for the decrease in the population of national children (-3.4 %). This resulted in an almost stable total child population (-1.0 %).

(2014=100)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

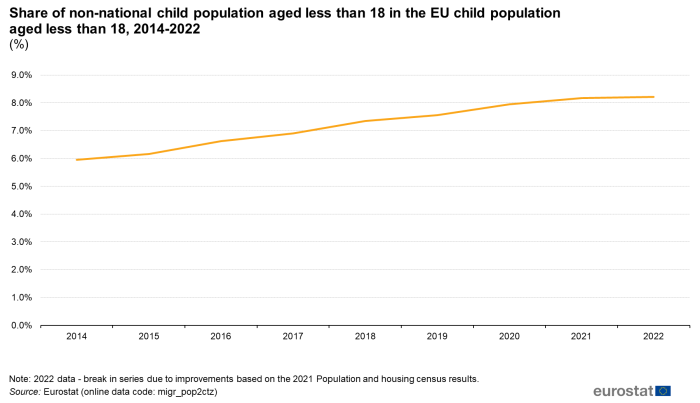

These opposing trends in the populations of non-national and national children led to a significant increase in the weight of the population of non-national children in the total child population in the EU, from 6.0 % in 2014 to 8.2 % in 2021 and 2022 (see Figure 6).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

Number of children aged less than 15 years in the EU by main groups of citizenship

Eurostat data collected on the stocks of non-nationals broken down by age group and main group of citizenship are available for the 27 EU Member States and non-EU countries for all the Member States and EFTA countries only for 2021 and 2022. Thus, in this article, from this paragraph onwards, the statistics provided before 2021 for the category EU citizens (excluding reporting country) include the citizens of the United Kingdom, while the statistics provided before 2021 for the category non-EU citizens exclude the citizens of the United Kingdom. This break in the presented time series implies a negative bias in 2021 in comparison with 2020 for EU citizens (removal of the United-Kingdom) and a positive bias in 2021 in comparison with 2020 for non-EU citizens (addition of the United-Kingdom).

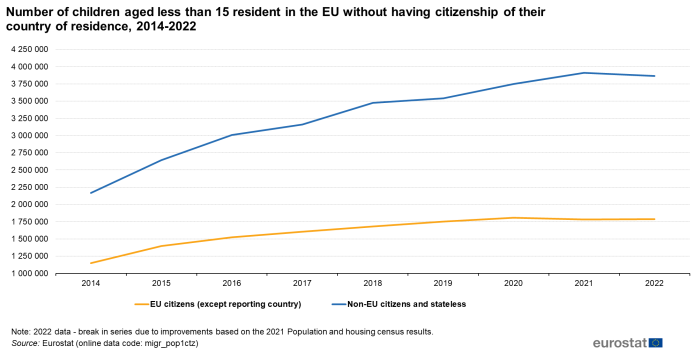

Figure 7 presents the trend in the number of children aged less than 15 years in the EU having either EU citizenship (excluding the reporting country) or non-EU citizenship (including stateless). In both cases, an upward trend is visible from 2014 to 2022, but the total growth of non-EU citizen children (+78.1 %) was higher than for EU citizen children (+55.7 %). On 1 January 2022, the number of non-EU citizen and stateless children was slightly more than twice (2.2) the number of EU citizen children.

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

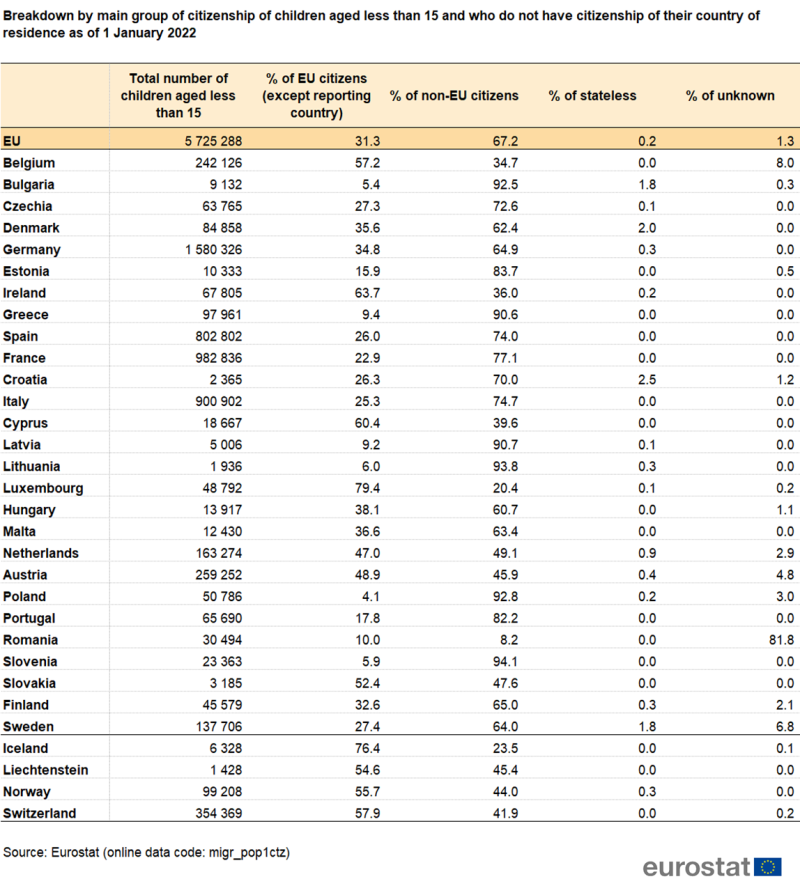

In 2022, slightly more than two out of three (67.2 %) non-national children aged less than 15 years were non-EU citizens or stateless. Table 2, which provides a breakdown by main group of citizenship for EU Member States and EFTA countries, shows that this structure can vary greatly from one country to another. In six Member States (Belgium, Ireland, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Austria and Slovakia), the majority of non-national children are EU citizens, whereas the Netherlands is the only other Member State where the share of EU children in the total number of non-national children was higher than 40 %. By contrast, in eight EU Member States (Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal and Slovenia) the share of non-EU children and stateless is higher than 80 %. Furthermore, in the four EFTA countries, the majority of non-national children aged less than 15 years have the citizenship of an EU Member State.

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

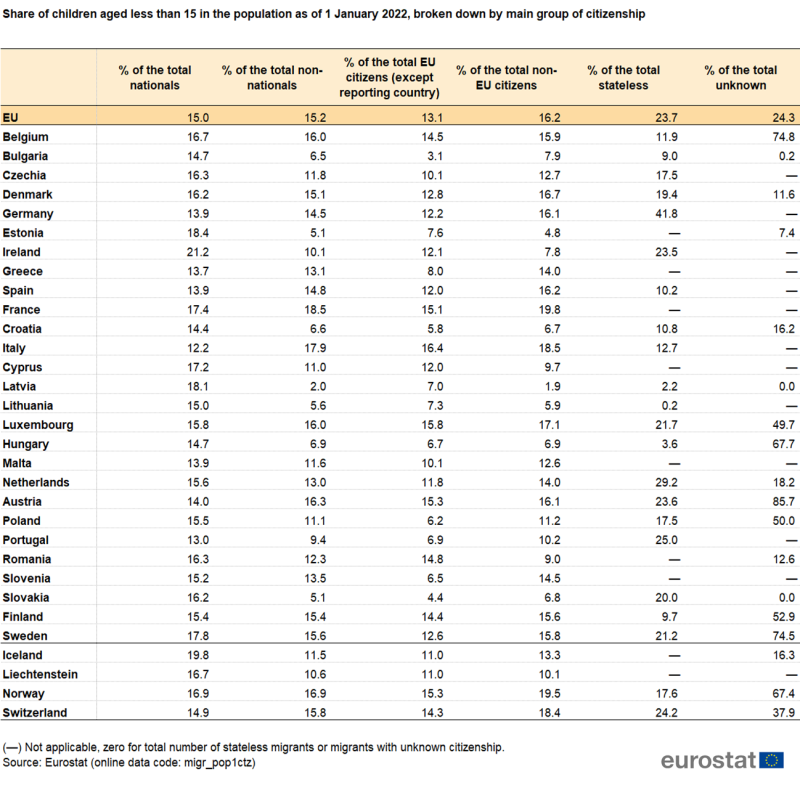

Table 3 presents the corresponding share of children aged less than 15 years in the total population for each main group of citizenship for the year 2022. At EU level, 15.0 % of the national residents were aged less than 15 years, whereas 15.2 % of non-national residents were aged less than 15 years. If those shares are comparable, this is not the case when looking at the share of children in the non-national population by main group of citizenship: 13.1 % for non-nationals with EU citizenship, 16.2 % for non-EU citizens, 23.7 % for stateless and 24.3 % for those with unknown citizenship. It indicates that the proportion of children in the migrant population depends on the relevant group of citizenship. This pattern observed at EU level is only found in Germany, Luxembourg and Austria and is different in all other EU Member States. The share of children in the non-national population with EU citizenship is for example higher than that for non-EU citizen children in six Member States (in Ireland, Cyprus, the Baltic countries and Romania).

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

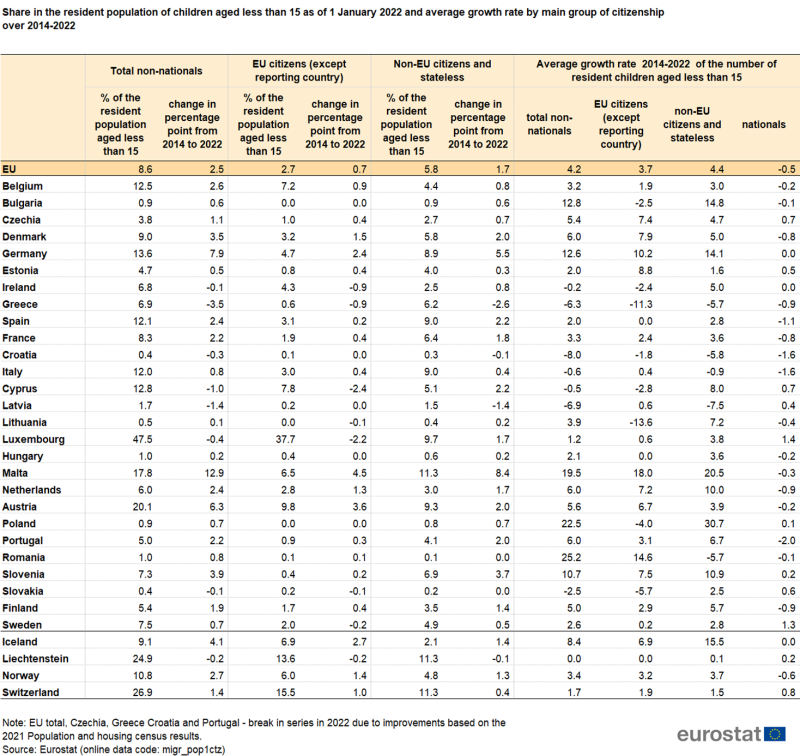

Table 4 provides some synthetic indicators on the trend in the population of non-national children aged less than 15 years in the EU, the Member States and the EFTA countries over 2014-2022. Among the eight EU Member States where the share of non-nationals in the child population aged less than 15 years is higher than 10 %, this share decreased only in Cyprus (-1.0 percentage points (pp)) and Luxembourg (-0.4 pp). By contrast, it increased slightly in Italy (+0.8 pp), Spain (+2.4 pp) and Belgium (+2.6 pp), whereas it increased more rapidly in three other EU Member States, in Malta (+12.9 pp), Germany (+7.9 pp) and Austria (+6.3 pp). In Malta and Germany, this increasing share of non-national children was mainly explained by the increasing share of non-EU citizen children, while in Austria by increasing share of EU citizen children.

When looking at the average yearly growth rates, the main feature at EU level involves the opposing trend followed by the number of national children (-0.5 %) and the number of non-national children (+4.2 %). In terms of geographical breakdown, the difference between EU and non-EU children is equal to 0.7 pp of growth on average per year (+3.7 % versus +4.4 %), but it corresponds in both cases to a significant growth. A positive growth rate in the number of national children can nevertheless be observed in ten of the EU Member States, with higher values recorded in Luxembourg (+1.4 %) and Sweden (+1.3 %). Negative growth rates for non-national children have been recorded in seven Member States (Ireland, Cyprus, Italy, Slovakia, Greece, Latvia and Croatia). Over the period in question, positive yearly growth rates higher than 10 % for the total number of non-national children were observed in six Member States (Bulgaria, Germany, Malta, Poland, Romania and Slovenia), with a higher growth rate recorded for non-EU citizen children than EU citizen children in all those countries, but one, Romania, where a negative yearly growth rate (-5.7 %) was observed for non-EU citizen children, while a positive growth rate of 14.6 % was recorded for EU citizen children.

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

Immigration of children aged less than 15 years by main groups of citizenship

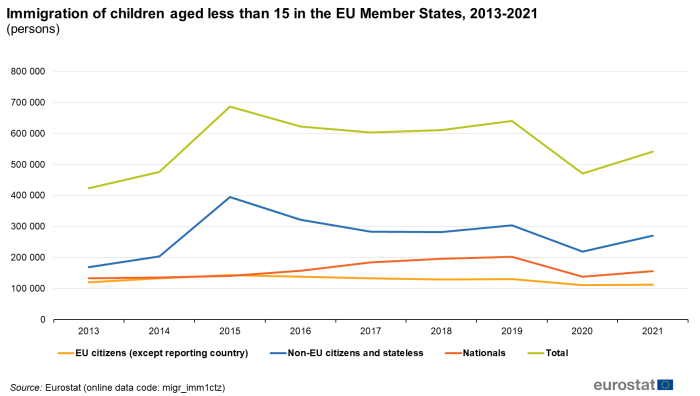

Immigration of children is one of the factors that influences the total number of non-national children in the total child population. In addition to EU citizen children, non-EU citizen children and stateless children, immigration statistics also include national children having immigrated in their country of citizenship. Figure 8 shows the trend from 2013 to 2021 in the immigration of children in the EU for those three main groups of citizenship. It should be noted that the EU aggregated figures presented here do not represent the immigration flows to the EU as a whole as they also include flows between different EU Member States. In order to compute the migration flows to the EU as a whole, it would be necessary to remove those intra-EU flows. Each group of citizenship followed a different path:

- The immigration of non-EU citizen and stateless children, which forms the main group over the whole period, peaked in 2015 linked to the 'migration crisis'. After peaking, it declined in the next 2 years, before increasing again in 2018 and 2019. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, a significant drop (-27.7 %) was recorded, while in 2021 the numbers increased again reaching a level of 271 087.

- The immigration of EU citizen children (excluding the reporting country) is characterised by an upward trend between 2013 and 2015 and a downward trend from 2015 onwards, accentuated in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic (-14.8 %). Over the entire period, the immigration of EU citizen children decreased by 6.5 % to reach 112 496 persons in 2021.

- The immigration of national children exhibited an upward trend from 2013 to 2019, but as for EU and non-EU citizen children, a strong decline in immigration of nationals (-31.8 %) was observed in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, 156 649 children migrated in their EU Member State of citizenship, a number comparable with that recorded in 2016 (157 705).

The trend in total child immigration was qualitatively comparable with that of non-EU citizen and stateless children, but with a total growth rate of 28.1 % over the period instead of 60.6 %.

(persons)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz)

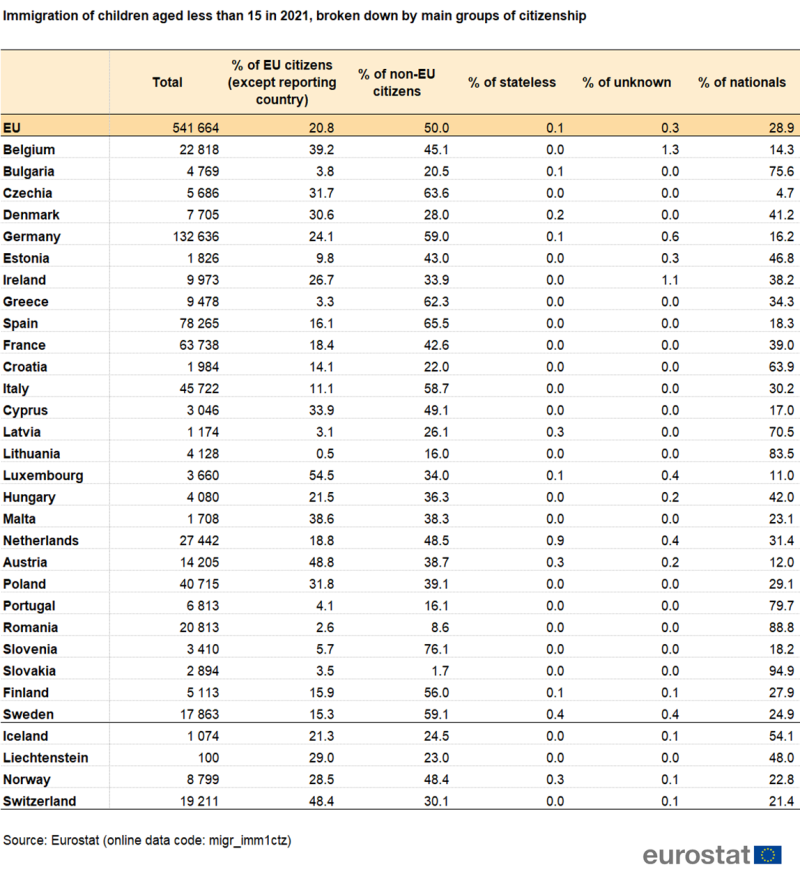

Table 5 provides the breakdown by main groups of citizenship for available EU Member States and EFTA countries in 2021. At EU level, every second immigrant child in the EU was a non-EU citizen, and almost one-third were nationals. In five Member States (Germany, Spain, France, Italy and Poland), the level of child immigration was higher than 40 000. In all those Member States, the share of non-EU citizens and stateless immigrant children was the highest. A share of nationals higher than 50 % of the total child immigration can also be found in Slovakia, Romania, Lithuania, Portugal, Bulgaria, Latvia and Croatia. By contrast, Luxembourg (54.5 %) was the only EU Member State where the share of EU citizens in the total child immigration was over 50 %. Slovenia (76.1 %), Spain (65.5 %), Czechia (63.6 %) and Greece (62.3 %) formed the Member States where the share of non-EU citizens in the total child immigration was the highest.

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz)

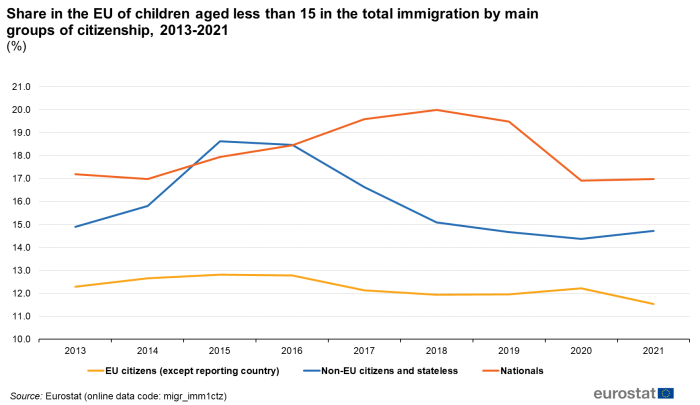

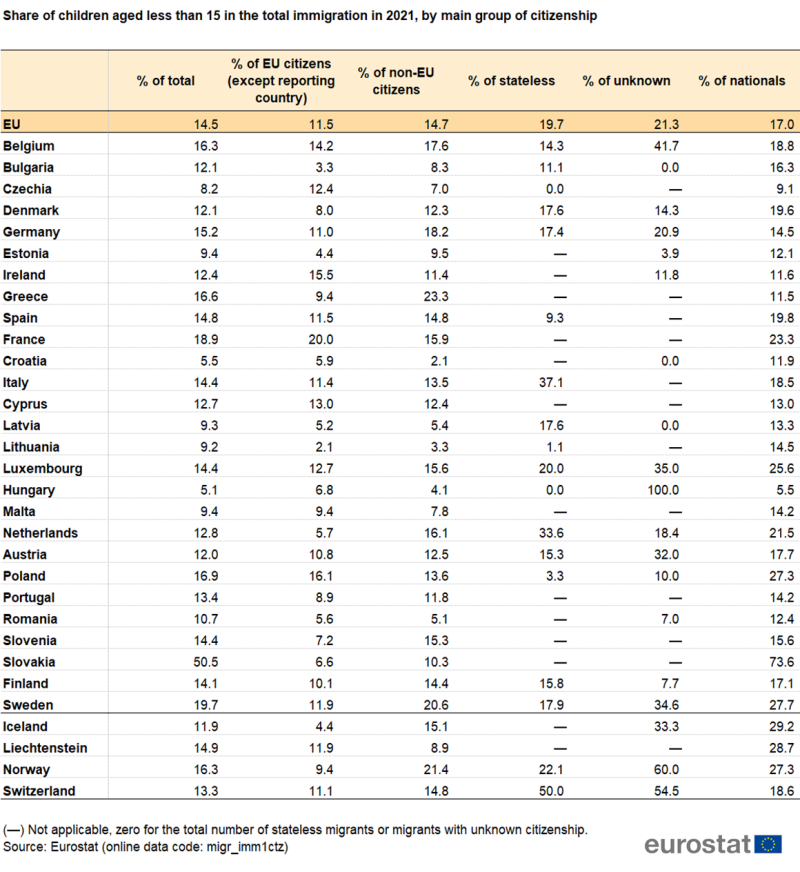

Figure 9 and Table 6 show the share of children aged less than 15 years in the total immigration in the EU by main group of citizenship. At EU level, the share of immigrant children is the highest for nationals, then for non-EU citizens and stateless and the lowest for EU citizen children. It should also be noted that the share of children in the total immigration is not stable, particularly for non-EU citizen and stateless children and national children. For example, this share for non-EU citizen and stateless children was the highest during the migration crisis in 2015-2016, whereas for national children it followed an upward trend from 2014 to 2018 before slightly dropping in 2019 and in a more pronounced way in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz) and Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz) and (migr_pop1ctz)

At EU Member State level, the highest share of children in the total immigration can be observed in Slovakia (50.5 %), ahead of Sweden (19.7 %) and France (18.9 %). For Slovakia, it was caused by the share of children in the immigration of nationals, which equalled 73.6 %. The highest shares of EU citizen children were recorded in France (20.0 %), Poland (16.1 %), Ireland (15.5 %) and Belgium (14.2 %), whereas the highest shares for non-EU citizen children were observed in Greece (23.3 %), Sweden (20.6 %), Germany (18.2 %) and Belgium (17.6 %).

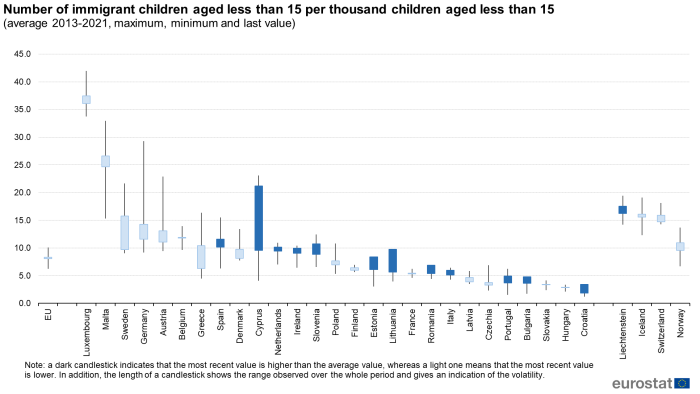

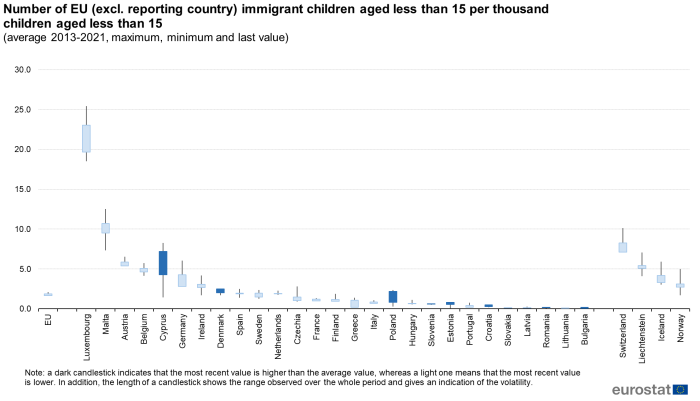

![]() Tables 7.a to 7.d as well as Figures 10.a to 10.d (presented below) show the ratio of the number of immigrant children aged less than 15 years per thousand resident children aged less than 15 years for the main groups of citizenship. It therefore provides an indication in relative terms of the weight of child immigration in the EU, the individual EU Member States and EFTA countries. Candlesticks in Figures 10.a to 10.d show the average, maximum (higher wick), minimum (lower wick) and most recent values of the ratios for each country. A dark candlestick indicates that the most recent value is higher than the average value, whereas a light one means that the most recent value is lower. In addition, the length of a candlestick shows the range observed over the whole period and gives an indication of the volatility.

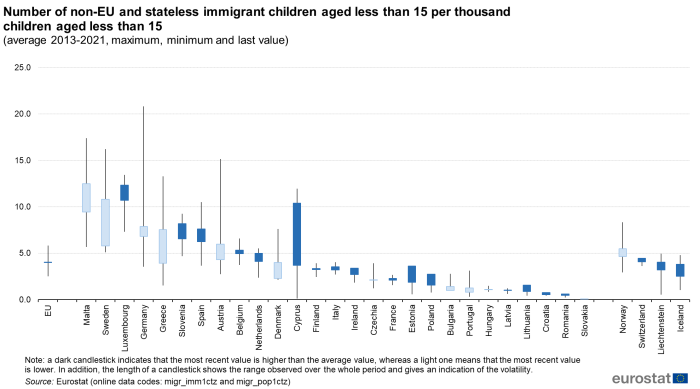

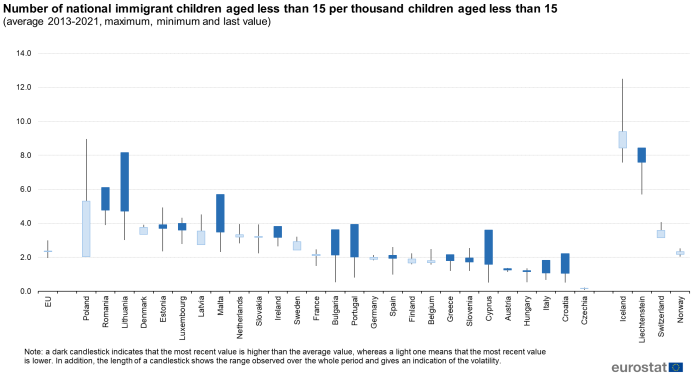

Tables 7.a to 7.d as well as Figures 10.a to 10.d (presented below) show the ratio of the number of immigrant children aged less than 15 years per thousand resident children aged less than 15 years for the main groups of citizenship. It therefore provides an indication in relative terms of the weight of child immigration in the EU, the individual EU Member States and EFTA countries. Candlesticks in Figures 10.a to 10.d show the average, maximum (higher wick), minimum (lower wick) and most recent values of the ratios for each country. A dark candlestick indicates that the most recent value is higher than the average value, whereas a light one means that the most recent value is lower. In addition, the length of a candlestick shows the range observed over the whole period and gives an indication of the volatility.

In Figure 10.a, the weight of children immigrants aged less than 15 years in the total resident children population aged less than 15 years recorded for 2021 was lower than the observed average over 2013-2021 in 15 Member States (light candlesticks), with a significant difference observed in Sweden, Greece and Germany. This may indicate the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the level of child immigration. By contrast, the most recent value available was higher than the average value in 12 EU Member States (dark candlesticks), in particular in Cyprus, Lithuania and Estonia.

(average 2013-2021, maximum, minimum and last value)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz) and Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

In Figure 10.b, which gives the weight of EU children immigrants aged less than 15 years in the total resident children population aged less than 15 years, EU immigrant children have on average a significant weight (more than 10 per thousand) in Luxembourg and Malta, and to a lesser extent in Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Germany and Ireland (more than 2.5 per thousand). The maximum value observed in 2021 for Cyprus can also be pointed out. Figure 10.b also shows that the range of candlesticks is reduced more in most of the Member States than for non-EU and stateless children (Figure 10.c) and national children (Figure 10.d). It therefore tends to confirm a more stable development in EU children immigration (see Figure 9).

(average 2013-2021, maximum, minimum and last value)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz) and Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

By contrast, the candlesticks in Figure 10.c are longer than in Figures 10.b and 10.d, which indicates a high level of volatility in non-EU and stateless children immigration. This pattern can be observed in particular in Germany, Austria, Greece, Sweden, Malta, Cyprus and Spain. The maximum value over the period 2013-2021 has been reached in 2021 in five Member States (Croatia, Romania, Lithuania, Poland and Spain), whereas there was no Member State recording the minimum value in 2021.

(average 2013-2021, maximum, minimum and last value)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz) and Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

Figure 10.d shows that the weight of national children immigration was on average higher than the EU average in 12 Member States (Poland, Romania, Denmark, Baltic countries, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Ireland, Malta and Sweden). A higher value in 2021 than the average has been observed in 16 Member States (dark candlestick) and a lower value than the average in 11 Member States (light candlestick).

(average 2013-2021, maximum, minimum and last value)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz) and Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

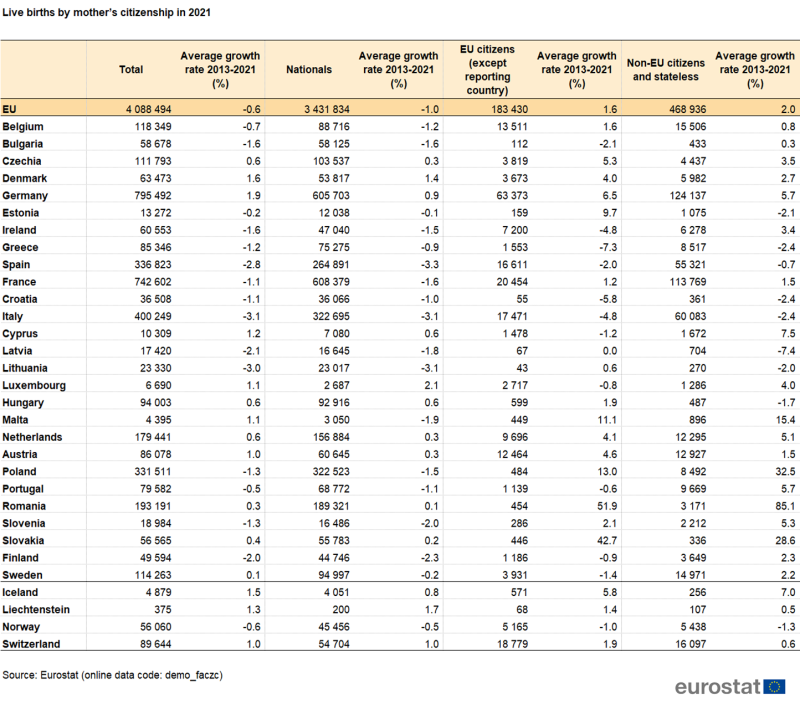

Live births by mother's citizenship

The number of births of non-national children is another factor influencing the share of non-national children in the total population of resident children. Table 8, which gives the number of live births by mother's citizenship in 2021, provides an indication to measure this phenomenon. It only deals with a proxy indicator since it does not give the citizenship of the child. In absolute terms, the number (183 430) of children born from an EU citizen mother (excluding the reporting country) and the number (468 936) from a non-EU citizen mother (including stateless mothers) was significantly higher in 2021 than the number of EU immigrant children (0-14 years old) and non-EU immigrant children (0-14 years old and including stateless immigrant children). Even if not all new-born children received only the citizenship of their mother, it shows that births have to be taken into account when analysing children in migration.

Table 8 also shows that at EU level, the yearly average growth rate of the total number of births (-0.6 %) was negative between 2013 and 2021, whereas it was positive for the number of live births recorded for foreign mothers with EU citizenship (+1.6 %) and non-EU citizenship (+2.0 %).

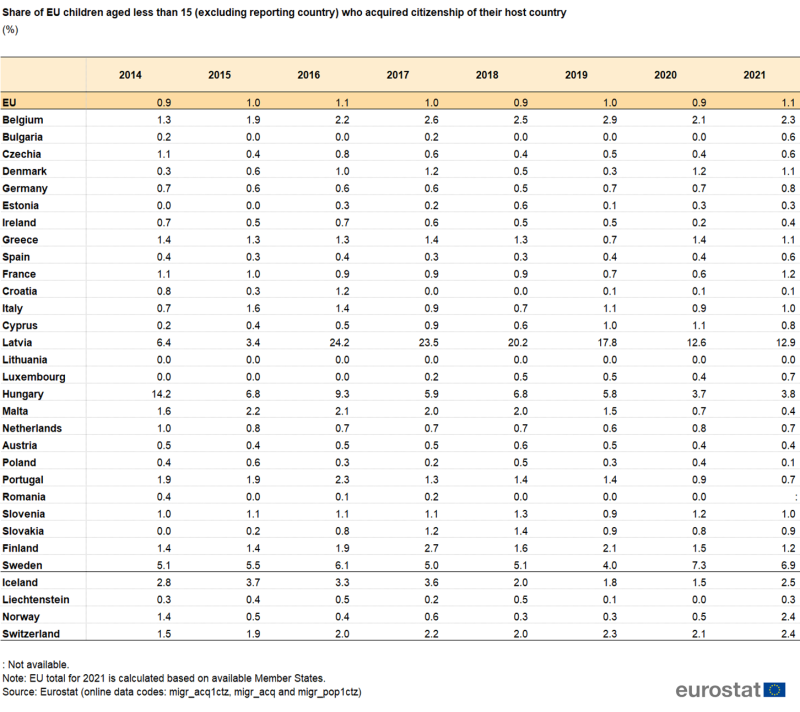

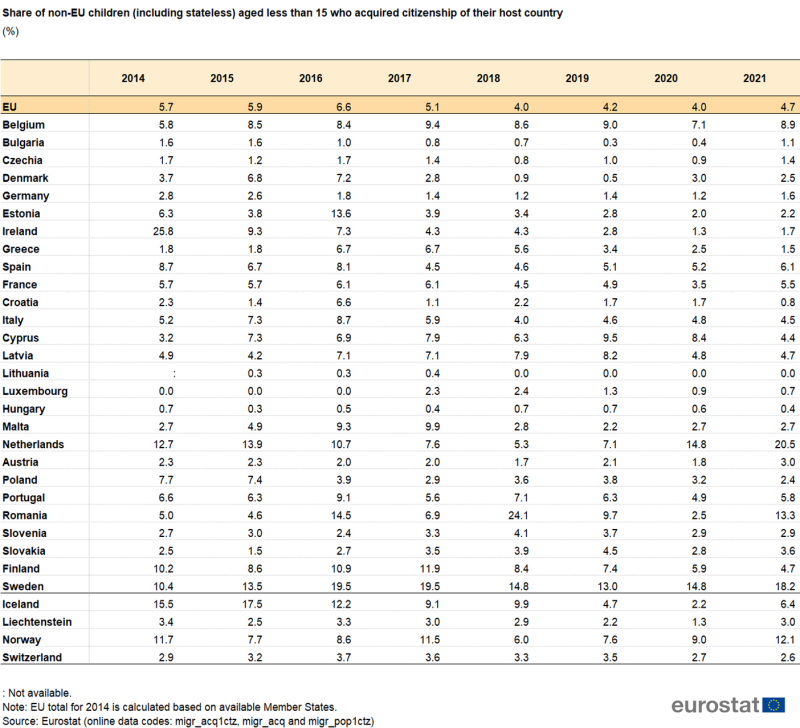

Acquisition of citizenship

Acquisition by migrant children of the citizenship of their country of residence is also a factor that should be taken into account when analysing children in migration. Table 9.a and Table 9.b give the share over 2014-2021 of non-national EU citizen children aged less than 15 years who acquired citizenship of their country of residence and the share of non-EU resident children aged less than 15 years who acquired citizenship of their country of residence respectively. At EU level, this share was equal to 1.1 % for EU children and 4.7 % for non-EU children in 2021. The share of EU children that had acquired the citizenship of their host country remained almost stable over the whole period, fluctuating between 0.9 % and 1.1 % for EU citizens, whereas the share of non-EU children that had acquired the citizenship of their host country ranged from 4.0 % in 2018 and 2020 to 6.6 % in 2016.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_acq1ctz) and (migr_acq) and (migr_pop1ctz)

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_acq1ctz) and (migr_acq) and (migr_pop1ctz)

At EU Member State level, the share of non-national children who acquired citizenship varies greatly from one country to another and over time. This share very much depends on the country's policies on the acquisition of citizenship. In 2021, the share of EU children who acquired citizenship was more than twice the EU average share in four Member States (Belgium, Latvia, Hungary and Sweden). On the share of non-EU citizens who acquired citizenship, it was higher than the EU average in seven Member States, with the four highest shares recorded in the Netherlands (20.5 %), Sweden (18.2 %), Romania (13.3 %) and Belgium (8.9 %).

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

This article presents European statistics on children in migration based on international migration (flows), the number of national and non-national citizens in the population (stocks) as well as data relating to live births by mother's citizenship and the acquisition of citizenship. It focuses mainly on flows and stocks of foreign and stateless children broken down by EU and non-EU citizens. Data are collected on an annual basis and are supplied to Eurostat by the national statistical authorities of the EU Member States and EFTA countries.

Legal sources

Since 2008, migration and international protection data have been collected based on Regulation (EC) No 862/2007. The analysis and composition of the EU, EFTA and candidate country groups as of 1 January of the reference year are given in Commission Regulation (EC) No 351/2010. This defines a core set of statistics on international migration flows, population stocks of foreigners, the acquisition of citizenship, residence permits, asylum and measures against illegal entry and stay. Although EU Member States may continue to use any appropriate data sources according to national availability and practice, the statistics collected under the Regulation (EC) No 862/2007 must be based on common definitions and concepts. Most EU Member States base their statistics on administrative data sources such as population registers, registers of foreigners, registers of residence or work permits, health insurance registers and tax registers. Some countries use mirror statistics, sample surveys or estimation methods to produce migration statistics. The implementation of the Regulation is expected to result in increased availability and comparability of migration statistics.

As stated in Article 2.1(a), (b), (c) of Regulation (EC) No 862/2007, immigrants who have been residing (or who are expected to reside) in the territory of an EU Member State for a period of at least 12 months are counted, as are emigrants living abroad for more than 12 months. Data collected by Eurostat therefore concern migration for a period of 12 months or longer: migrants therefore include people who have migrated for a period of one year or more as well as persons who have migrated on a permanent basis. Eurostat collects data on acquisitions of citizenship under the provisions of Article 3.1.(d) of Regulation (EC) No 862/2007, which states that 'Member States shall supply to the Commission (Eurostat) statistics on the numbers of (…) persons having their usual residence in the territory of the Member State and having acquired during the reference year the citizenship of the Member State (…) disaggregated by (…) the former citizenship of the persons concerned and by whether the person was formerly stateless'.

Notes: Data on acquisitions of citizenship for Germany are provisional for 2018 and 2019 and are rounded to the nearest five from 2018 onwards. The EU totals on acquisitions of citizenship data by single former citizenship are computed based on available Member States:

- Table 9.a. Share of EU children aged less than 15 years (excluding reporting country) who acquired citizenship of their host country

- 2021: data by individual former citizenship are not available for Romania

- Table 9.b. Share of non-EU children (including stateless) aged less than 15 years who acquired citizenship of their host country

- 2014: data by individual former citizenship are not available for Lithuania

Age: On the definitions of age for migration flows, 2021 data concern the respondent's age reached or age at the end of the reference year for all EU Member States with the exception of Ireland, Greece, Austria, Malta, Romania and Slovenia. In these countries, data concern the respondent's age completed or age on their last birthday. On the definitions of age for acquisitions of citizenship, 2021 data concern the respondent's age reached or at the end of the reference year for all EU Member States with the exception of Germany, France, Greece, Ireland, Austria, Lithuania, Malta, Poland and Slovenia. In these countries, data concern the respondent's age completed or age on their last birthday.

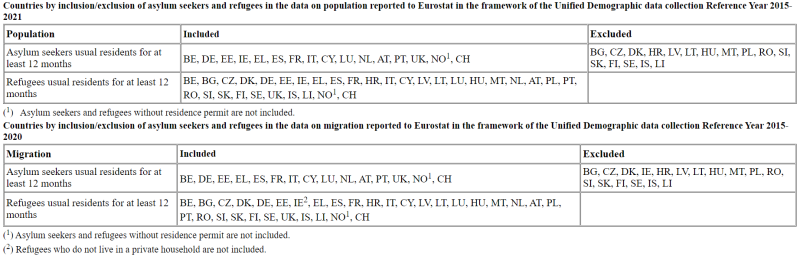

Countries by inclusion/exclusion of asylum seekers and refugees in the data on population and migration reported to Eurostat:

Refugee: The term does not solely refer to persons granted refugee status (as defined in Art.2(e) of Directive 2011/95/EC within the meaning of Art.1 of the Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees of 28 July 1951, as amended by the New York Protocol of 31 January 1967) but also to persons granted subsidiary protection (as defined in Art.2(g) of Directive 2011/95/EC) and persons covered by a decision granting authorisation to stay for humanitarian reasons under national law concerning international protection.

Asylum seeker: First-time asylum applications are country-specific and imply no time limit. An asylum seeker can therefore apply for the first time in a given country and afterwards again as a first-time applicant in any other country. If an asylum seeker lodges another application in the same country after any period of time, they are not considered a first-time applicant again.

Methodological notes:

- For the purpose of this Statistics Explained, the distinction between EU and non-EU citizens for the stocks of migrants and immigration flows is based on the composition in force at the time of reference of data. Therefore, for non-EU child migrants, citizens from the United-Kingdom are counted as EU citizens from 1 January 2013 to 1 January 2020 while they are counted as non-EU citizens in 2021 and 2022 data. For immigration flows, citizens from the United-Kingdom are counted as EU citizens from 2013 to 2020 while they are counted as non-EU citizens in 2021. This break in the presented time series implies a negative bias in EU citizens (removal of the United-Kingdom) and a positive bias for non-EU citizens (addition of the United-Kingdom).

- Non-national category includes the following categories: EU citizens (excluding the reporting country), non-EU citizens, stateless and unknown.

- Data on immigration and acquisition of citizenship can be based either on the age reached during the year or on the age in the completed year. Other data are solely based on the age reached during the year.

Context: EU migration policy

In recent years, the number of children in migration[1] arriving in the European Union, many of whom are unaccompanied, has increased in a dramatic way, particularly in 2015 and 2016. Beside asylum applicants, a significant number of non-EU children are migrating for family reasons.

Protecting children is first and foremost about upholding European values of respect for human rights, dignity and solidarity. This is why protecting all children in migration, regardless of status and at all stages of migration, is a priority. The European Union, together with its Member States and with the support of the relevant EU agencies (European Border and Coast Guard Agency; European Asylum Support Office (EASO) and the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA)), has been active on this front for many years. The existing EU policies and legislation provide a solid framework for the protection of the rights of the child in migration covering all aspects including reception conditions, the treatment of their applications and integration.

The protection of children in migration starts by addressing the root causes which lead so many of them to embark on perilous journeys to Europe. This means addressing the persistence of violent and often protracted conflicts, forced displacement, inequalities in living standards, limited economic opportunities and access to basic services by making sustained efforts to eradicate poverty and deprivation and develop integrated child protection systems in non-EU countries. The European Union and its Member States have stepped up their efforts to establish a comprehensive external policy framework to reinforce cooperation with partner countries in mainstreaming child protection at the global, regional and bilateral level. The European Union is fully committed to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which calls for a world in which every child grows up free from violence and exploitation, has his/her rights protected and access to quality education and healthcare. The 2015 Valletta Summit[2] political declaration and its Action Plan calls for the prevention of and fight against irregular migration, migrant smuggling and trafficking in human beings (with a specific focus on women and children).

The EU Guidelines on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of the Child renew the EU's commitment to promote and protect the indivisibility of the rights of the child in its relations with non-EU countries, including countries of origin or transit. In this context, the Council reaffirmed the need to protect all refugee and migrant children, regardless of their status, and give primary consideration at all times to the best interests of the child, including unaccompanied children and those separated from their families, in full compliance with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and its Optional Protocols.

Within the European Commission, the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs is responsible for immigration policy, whereas the Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers is in charge of child policy. All relevant legal acts and information regarding the EU's immigration policy can be accessed on the European Commission's website. Readers interested in the recent development of the global immigration policy in the European Union can also refer to the New Pact on Migration and Asylum which has been presented by the European Commission in September 2020.

The New pact on Migration and Asylum underlines that the EU asylum and migration management system needs to provide for the special needs of vulnerable groups, including children. In particular, the reform of EU rules on asylum and return is an opportunity to strengthen safeguards and protection standards under EU law for migrant children with the following goals:

- The right for the child to be heard in the context of asylum and migration proceedings.

- Unaccompanied minors should be appointed a guardian within 15 working days.

- Unaccompanied minors and families with children under 12 years to be exempted from the mandatory border procedure.

- Develop effective alternatives to detention for children and their families.

- Rules on evidence required for family reunification simplified.

- The right to adequate accommodation and assistance, prompt and non-discriminatory access to education, and early access to integration services, will be reinforced.

Direct access to

Methodology

- Population (national level) (ESMS metadata file — demo_pop_esms)

- International Migration statistics (ESMS metadata file — migr_immi_esms)

- Acquisition and loss of citizenship (ESMS metadata file — migr_acqn_esms)

- DG for Migration and Home Affairs — Legal migration and Integration

- DG Justice and Consumers — Policies

- DG for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion — European Child Guarantee

- The EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child and the European Child Guarantee

- New Pact on Migration and Asylum

- JRC Publications Repository — Data on Children in Migration

- International Data Alliance for Children on the Move (IDAC)

Notes

- ↑ The terms 'children in migration' or 'children' in this document cover all non-EU country national children (persons below 18 years old) who are forcibly displaced or migrate to and within the EU territory, be it with their (extended) family, with a non-family member (separated children) or alone, whether or not seeking asylum.

- ↑ https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/21839/action_plan_en.pdf