Archive:Social participation statistics

- Data from December 2010. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Data from a new ad hoc module of the EU-SILC on Social participation will be available by the end of 2016. The article will be updated accordingly.

First author: Orsolya Lelkes, European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research (Vienna, Austria)

This article analyses data on social isolation in the European Union (EU), collected via an ad-hoc module of the EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). About one out of fourteen EU citizens was found to be socially isolated, never meeting friends or relatives, or not in a position to receive help if needed.

The analysis provides some insight in factors affecting social isolation. It increases in old age, is higher among those who are at risk of poverty and shows geographical variation as well: Mediterranean countries, especially Cyprus, Portugal and Greece, tend to be more ‘social’. Friendship ties appear to be cultivated more than family ties: in the majority of European countries, people are more likely to maintain close contact with friends than with relatives.

Main statistical findings

In 2006, 7.2% of EU citizens were found to be socially isolated: which means that they never meet friends or relatives, or that they cannot receive help if needed. Social isolation increases in old age, and it is higher among those who are at risk of poverty. There is little variation in the total level of social contacts: over three quarters of the population meet relatives or friends at least once a month in all the countries. However, there are major differences in terms of the intensity of these contacts. The Mediterranean countries tend to be among the most ‘social’, especially Cyprus, Portugal and Greece, where about 40% or more meet friends on a daily basis. Friendship ties appear to be cultivated more than family ties: in the majority of European countries, people are more likely to maintain close contact with friends than with relatives.

Social isolation

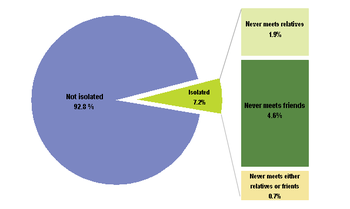

In 2006, 7.2% of Europeans were socially isolated: this is the share of the population who said that they never meet friends or relatives, not even once a year. This figure, calculated as a weighted average of national results, can be regarded as an extreme degree of isolation, which is somewhat at variance with contemporary social standards, given that in most countries people typically meet every week. Social isolation can be regarded as a measure of social exclusion.

Relative, friend and neighbour - basis of social ties

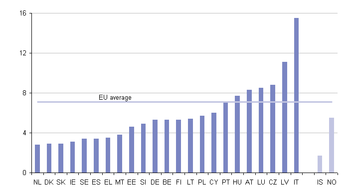

Family ties are stronger than friendship ties, in the sense that relatives are more likely to provide a last resort in terms of personal contacts. While 4.6% (between 2% and 16% in the particular countries) say that they ‘never’ meet friends, not even ‘once a year’; a smaller share, 1.9% (0.6-5.2%) of the population say that they ‘never’ meet relatives. When observing the overlap between these groups, we find that it is relatively small: only 0.7% say that they do not meet either friends or relatives. The overall majority of people in European countries are able to call on the help of a relative, friend or neighbour if necessary. The share of those who say that they cannot is 7% in the EU on average and the range is between 2% and 16% (Figure 2).

Note that the questionnaire covers help from relatives and friends who do not live in the same household as the respondent. Few people regard themselves as socially isolated in the Netherlands, Denmark, Slovakia, Ireland, Sweden, Spain and Greece. On the other hand, a relatively high share of the population think that they cannot ask for and receive help in Austria, Luxembourg, the Czech Republic, Latvia and Italy. In the latter two countries, the share is as high as 11.1% and 15.5% respectively. Interestingly, there are no obvious geographical patterns. For example, Slovakia, with its low level, is markedly different from the neighbouring Czech Republic, Austria and Hungary, all of which have above-average levels. Italy also appears to be quite distinct from the other Mediterranean countries, especially Greece and Spain.

Social network provides help

The inability to ask for help is strongly related to the individual’s social network, the intensity of social contacts with friends and kin. As Table 1 shows, the ability to ask for help declines as meetings become more sporadic. There is a particularly marked cut-off point for those who never meet friends or relatives (or do not have any), and these are the people most at risk of becoming socially isolated. Only 54.5% of these are able to ask anyone for help, which is much lower than among those who do have some personal contacts with relatives or friends, even if it is only once a year (79.6%).

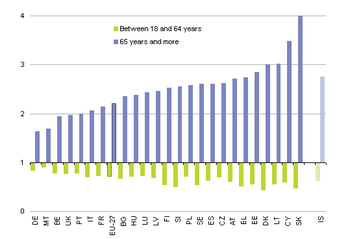

Social isolation increases with age

The old age population is affected by the break-up of friendships or the death of friends, and the growing difficulty of replacing these relationships. As a result, in two thirds of the countries, over 1 in 10 persons aged 65 or more have no friends or never meet them. This share increases to more than 1 in 4 in case of Hungary and Latvia, indicating that a large proportion of elderly people are isolated. As Figure 3 shows, the relative disadvantage of those aged 65 or more is three or more times higher in many countries compared to the total population, including Denmark, Latvia, Cyprus and Slovakia. The figures show the ratio of those with no friends by age group compared to the total population, thus checking for country level differences. Our calculations also show that family and relatives play a major role in preventing isolation in old age: significantly fewer people claim to have no relatives or no contact with them than in the case of friends.

Social isolation is greater among those at risk of poverty

The population at risk of poverty (with an equivalised disposable income below 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income) tends to be exposed to greater social isolation: the share of those with no friends is significantly higher among this population in all EU countries examined here (Figure 4). The relative disadvantage of those on low incomes is particularly high (with rates that are at least twice as high) in 12 out of 25 countries. Cyprus, in particular, stands out with a ratio of 4.5 (7.7% of the poor have no friends, whereas the corresponding ratio among the non-poor population is only 1.7%). Poverty may cause social isolation, e.g. if people cannot afford to go out with friends or invite them to their homes. On the other hand, social isolation may also ultimately lead to poverty, as friends and acquaintances (primarily the so-called ‘bridging social capital’) can provide useful support in finding (good) jobs. The direction of causality is thus not clear. We know, however, that such situations are not desirable, and the accumulation of social isolation and poverty flags up the risk of social exclusion.

Major differences in the intensity of personal contacts

There is little variation in the total level of social contacts: over 75% of the population meet friends at least once a month in all the countries (see Figure 5). If we focus on daily meetings, however, there is much greater cultural divergence across Europe. The Mediterranean countries tend to be among the most ‘social’ - especially Cyprus, Greece and Portugal, where about 40% or more meet friends or relatives on a daily basis. At the other end France, Austria, Latvia and Denmark, where around 12% meet friends every day. All in all, the cultural differences arise not with respect to maintaining relationships with friends as such, but rather with respect to the intensity of these contacts.

More intensive social life with friends than with relatives

Friendship ties appear to be nurtured more than family ties: in the majority of European countries, people are more likely to maintain close relationship with friends than with relatives. This is particularly so in the Baltic Member States, Bulgaria and some other countries, where the majority of the population meets relatives less often than every week. On the other hand, however, in Cyprus, Greece and Portugal, which are characterised by intensely maintained friendships, family contacts remain important: over 70% of the population get together at least once a week with both family and friends. In Malta - the EU country where family contacts appear to be the most nurtured - contacts with friends are much less intense. Note, however, that this measure does not explore the depth and nature of these relationships, or the potential personal support arising from them. Thus, ‘getting together with friends’ might imply rather different things in specific cultural contexts. (see Figure 6, EU-27(s) means that it an estimation).

Data sources and availability

The calculations are based on the 2006 ad-hoc module on social participation of EU-SILC. Data are either from the Users’ database or available via downloadable ad-hoc modules (Excel files).

This study covers 26 out of the 27 Member States. Only Romania is not covered in this study. The module was surveyed on the same sample as the main questionnaire. In some countries (Finland, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Sweden), however, it covered only a subsample. The sample size for this module varies between 6 779 individuals (Sweden) and 45 975 individuals (Italy).

EU-SILC was implemented in order to provide underlying data for these indicators. Organised under a Framework Regulation 1177/2003, it is now the reference source for statistics on income and living conditions and for common indicators for social inclusion in particular. In the context of the Europe 2020 agenda, the European Council adopted in June 2010 a headline target on social inclusion. EU-SILC is the reference source for the three sub-indicators on which this new target is based.

Context

Social participation and social isolation are currently not part of the set of common statistical indicators of social exclusion. The paper explores new indicators, which are but could be potentially considered as an extension to the current set of common indicators. At the Laeken European Council in December 2001, European heads of state and government endorsed a first set of common statistical indicators of social exclusion and poverty that are subject to a continuing process of refinement by the Indicators Sub-Group of the Social Protection Committee. These indicators are an essential element in the Open Method of Coordination to monitor the progress of Member States in the fight against poverty and social exclusion.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Income and living conditions in Europe, Chapter 10: Social participation and social isolation, p. 217-240, author: Orsolya Lelkes

Main tables

Database

- Population at risk of poverty or social exclusion (Europe 2020 strategy) (ilc_pe)

- Main indicator - Europe 2020 target on poverty and social exclusion (ilc_peps)

- Population at risk of poverty or social exclusion by age and gender (ilc_peps01)

- Population at risk of poverty or social exclusion by most frequent activity status (population aged 18 and over) (ilc_peps02)

- Population at risk of poverty or social exclusion by income quintile and household type (ilc_peps03)

- Population at risk of poverty or social exclusion by education level (population aged 18 and over) (ilc_peps04)

- Population at risk of poverty or social exclusion by broad group of citizenship (population aged 18 and over) (ilc_peps05)

- Population at risk of poverty or social exclusion by broad group of country of birth (population aged 18 and over) (ilc_peps06)

- Intersections between sub-populations of Europe 2020 indicators on poverty and social exclusion (ilc_pees)

- Intersections of Europe 2020 Poverty Target Indicators by age and gender (ilc_pees01)

- Intersections of Europe 2020 Poverty Target Indicators by most frequent activity status (population aged 18 and over) (ilc_pees02)

- Intersections of Europe 2020 Poverty Target Indicators by income quintile (ilc_pees03)

- Intersections of Europe 2020 Poverty Target Indicators by type of household (ilc_pees04)

- Intersections of Europe 2020 Poverty Target Indicators by education level (population aged 18 and over) (ilc_pees05)

- Intersections of Europe 2020 Poverty Target Indicators by broad group of citizenship (population aged 18 and over) (ilc_pees06)

- Intersections of Europe 2020 Poverty Target Indicators by broad group of country of birth (population aged 18 and over) (ilc_pees07)

- Main indicator - Europe 2020 target on poverty and social exclusion (ilc_peps)

Dedicated section

Source data for tables, figures and maps on this page (MS Excel)

Methodology / Metadata

- Eurostat - Feasibility study for Well-Being Indicators

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

- The production of data on homelessness and housing deprivation in the European Union: survey and proposals

Other information

- Regulation 1177/2003 of 16 June 2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation 1553/2005 of 7 September 2005 amending Regulation 1177/2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation 1791/2006 of 20 November 2006 adapting certain Regulations and Decisions in the fields of ... statistics, ..., by reason of the accession of Bulgaria and Romania

External links

- Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress

- European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research

- OECD - Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs - Society at a Glance 2011 - OECD Social Indicators

- The New Economics Foundation (NEF), UK - National Accounts of Well-being

- The World Bank - Measuring Social Capital