Archive:Quality of life indicators - productive or main activity

This article has been archived.

Highlights

In 2020, the share of employees who worked under a temporary contract because they could not find a permanent job ranged from 0.3 % in Estonia to 19.5 % in Spain.

Share of employees with a temporary contract aged 15-64 years that could not find a permanent job, 2020

This article is part of a Eurostat online publication that focuses on Quality of life indicators, providing recent statistics for the European Union (EU). The publication presents a detailed view of various dimensions that can form the basis for a more profound analysis of the quality of life, complementing gross domestic product (GDP) which has traditionally been used to provide a general overview of economic and social developments.

The focus of this article is the second dimension — productive or main activity — of the nine quality of life indicators dimensions that form part of a framework, endorsed by an expert group on quality of life indicators. The term productive or main activity refers to gainful or recompensed work (for example directly paid as an employee, or indirectly recompensed as a self-employed person or unpaid family worker), referred to hereafter as paid work, unpaid work (for example, unpaid work caring for family members or volunteering) and other types of main activity status (for example, studying or retirement).

Assessing the effect of working life on the overall quality of life is a complex matter as many complementary aspects of a person’s activity have to be taken into account. Broadly speaking, the quantity as well as the quality of employment needs to be measured.

Full article

Productive or main activity in the context of quality of life

While the employment indicators analysed in this article refer only to gainful employment, work affects quality of life not only because of the income it generates but also because of the role it plays in giving people their sense of identity and opportunities for social contact with others.

Paid work usually takes up a significant part of a person’s time and can have a significant impact on their quality of life. Work generates an income, provides a sense of identity and also offers opportunities for social contact, to be creative, to learn new things and to engage in activities that give a sense of fulfilment and enjoyment. Conversely, a person’s quality of life may deteriorate when, through work, they experience discrimination, harassment, insecurity or fear of physical injury, or have to work long hours for what they consider to be inadequate pay. A lack of work or unemployment potentially threatens a person’s psychological health.

Assessing the effect of paid work on quality of life is a complex task which requires several factors to be taken into account, covering various complementary aspects of a person’s main activity. Broadly speaking, the aspects that need to be measured are the quantity and the quality of employment. An indicator used for assessing the quantity or lack of employment is unemployment, including long-term unemployment. As noted in the Joseph E. Stiglitz, Amartya Sen and Jean-Paul Fitoussi report, ‘people who become unemployed report lower life-evaluations, even after controlling for their lower income, and with little adaptation over time; unemployed people also report a higher prevalence of various negative effects (sadness, stress and pain) and lower levels of positive ones (joy). These subjective measures suggest that the costs of unemployment exceed the income-loss suffered by those who lose their jobs, reflecting the existence of non-pecuniary effects among the unemployed and of fears and anxieties generated by unemployment in the rest of society’.

Involuntary temporary work and involuntary part-time employment are on the border between quantity and quality of employment. An indicator of involuntary part-time employment is used as a proxy for underemployment (working less than one is able and willing).

The quality of employment is measured by various sub-dimensions, within a framework developed by a joint UNECE/Eurostat/OECD Task Force, including income and benefits (the incidence of low earnings), over-qualification, work-life balance (based on the average number of hours worked and night time working) and health and safety at work (the incidence of work-related accidents). Information is also available concerning the overall perception of an individual’s satisfaction with their current job.

It should be noted that employment quantity and quality are complementary and, therefore, not to be substituted when it comes to measuring improvements in the quality of life. Improvements in quantity tend to affect the unemployed and the underemployed the most, whereas improvements in quality affect people who are in employment. The complementarity between employment quantity and quality as regards well-being has been reflected in the European Commission’s European employment strategy (EES) for more and better jobs.

Most of the indicators which are examined below are objective; in other words, they measure observed characteristics of the labour market. However, it is also important to balance these through the use of subjective indicators, such as an individual’s satisfaction with their work.

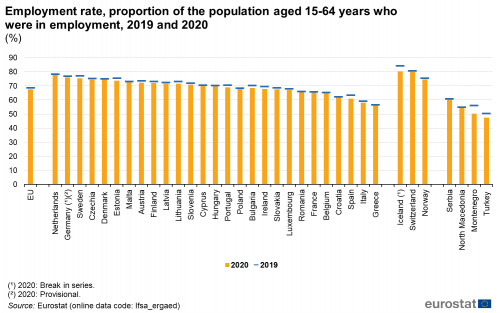

Quantitative aspects of employment

In 2020, the employment rate (in other words the number of persons employed aged 15-64 years as a proportion of the population of the same age group) in the EU was 67.6 %, compared with 63.3 % in 2010 (see Figure 1). The EU Member State with the highest employment rate in 2020 was the Netherlands, where 77.8 % of the working age population were employed. Sweden and Germany had employment rates above 75.0 %. At the other end of the ranking, Greece had the lowest employment rate in the EU, as just over half (56.3 %) of its working-age population were in employment, with Belgium, Croatia, Spain and Italy also recording rates that were below 65.0 %.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_ergaed)

When comparing the situation in 2020 with 2019, it can be clearly seen that the pandemic had an impact on the labour markets within the EU, as employment rates decreased after a period of uninterrupted increases at EU level which started in 2014. Between 2019 and 2020, employment rates decreased in all Member States with the exception of Malta and Poland, where a slight increase of 0.6 and 0.5 percentage points respectively was recorded. The largest decrease was recorded in Spain (minus 2.4 pp.), the only Member State with a drop of more than 2 percentage points. Seven EU countries saw a decrease in employment between 1 and 2 percentage points.

Unemployment and long-term unemployment

Unemployment is strongly associated with low levels of life satisfaction and happiness. The link between unemployment and underemployment and lower subjective well-being has been documented in several studies (see Abdalallah, Stoll and Eiffe, 2013 for a review).

In 2020, in the EU, the unemployment rate - which is the percentage of people actively looking for employment in the total labour force (also known as the economically active population) - was 7.1 % for the age group 15-74 years (see Figure 2). The long-term unemployment rate, the percentage of people who have been unemployed for at least one year in the total labour force, was 2.4 %. Looking from a different perspective, 33.8 % of all unemployed people in the EU had been unemployed for at least a year.

(12 months or more) rates, 2020

(% of labour force aged 15-74 years)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_urgaed) and (une_ltu_a)

The EU Member States with the highest unemployment rates in 2020 were Greece and Spain, with 16.3 % and 15.5 % respectively of their labour force unemployed. Czechia had the lowest unemployment rate in the EU, 2.6 %, followed by Poland (3.2 %), the Netherlands and Germany (both at 3.8 %).

The EU Member States with the highest overall unemployment rates also generally recorded the highest long-term unemployment rates, with some differences in the latter ranking. Greece again had the highest rate, as 10.9 % of its labour force had been unemployed for at least a year, more than double the next highest rate which was 5.0 % in Spain. The next highest long-term unemployment rate was 4.7 % in Italy. As for the overall unemployment rate, Czechia also recorded the lowest long-term unemployment rate among the Member States together with Poland (both at 0.6 %), followed by the Netherlands and Denmark (both at 0.9 %). It is important to note that although the unemployment rate is almost the same in Lithuania and Sweden (8.5 % and 8.3 % respectively), long-term employment is more than twice as high in the former (2.5 %) compared to the latter (1.1 %).

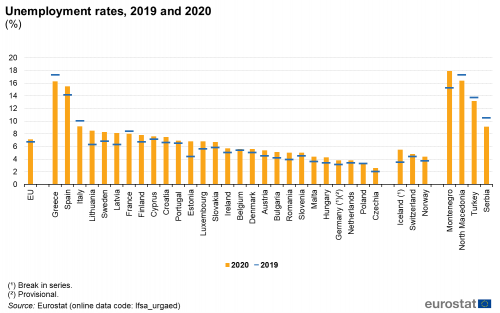

Unemployment in times of COVID

Figure 3 compares unemployment rates before and during the first stage of the COVID pandemic. Overall in the EU the unemployment rate increased slightly by 0.4 percentage points between 2019 and 2020. However, there were big discrepancies between the Member States. The largest increase in unemployment was observed in Estonia (plus 2.4 percentage points), followed by Lithuania (plus 2.2 pp). Six Member States (Latvia, Sweden, Spain, Luxembourg, Romania and Finland) saw their unemployment rate increasing between 1 and 2 percentage points. All other EU countries recorded a rise between zero and one percentage points. Nevertheless, there were four EU countries were unemployment decreased during the pandemic: Greece (minus 1.0 pp), Italy (minus 0.8 pp), France (minus 0.4 pp) and Poland (minus 0.1 pp).

Similarly, unemployment rose in the EFTA countries during the pandemic, whereas the situation in the candidate countries was not as clear cut. Only one of them (Montenegro) saw an increase whereas the other countries recorded a drop in their unemployment rates.

(% of labour force aged 15-74 years)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_urgaed)

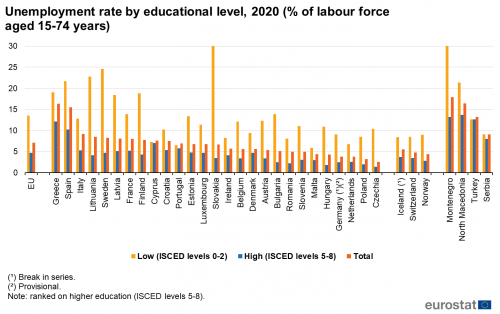

Unemployment by level of educational attainment

In all EU Member States, people with a high level of educational attainment were less likely to be unemployed than people with a low level of educational attainment. In 2020, the unemployment rate in the EU was 13.5 % for people with a low level of education (having completed at most lower secondary education), some 2.9 times as high as the 4.7 % rate for people with a high level of education (having a tertiary level of educational attainment) — see Figure 4.

(% of labour force aged 15-74 years)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_urgaed)

The greatest difference in unemployment rates observed for people with the lowest and the highest levels of educational attainment was recorded in Slovakia, where the unemployment rate for people with a low level of educational attainment was 30.6 %, some 27.1 percentage points higher than the rate for people with a high level of educational attainment (3.5 %). A further six EU Member States reported a gap of at least 10.0 percentage points, including a gap of 19.9 percentage points in Sweden, the second highest gap. The narrowest educational gap in unemployment rates was in Cyprus, where the rate for people with a low level of educational attainment (7.3 %) was 0.3 percentage points higher than the rate for people with a high level of attainment (7.0 %). Other Member States where the educational gap was below 5.0 percentage points included Croatia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Ireland, Malta and Portugal.

Quality of employment

Involuntary temporary work

An employee is considered as having a temporary job if employer and employee agree that its end is determined by objective conditions, such as a specific date, the completion of an assignment, or the return of an employee who is temporarily replaced. Such contracts are referred to by a variety of names, including temporary contracts, limited duration contracts or fixed-term contracts. Typical cases include: people in seasonal employment; people engaged by an agency or employment exchange and hired to a third party to perform a specific task (unless there is a written work contract of unlimited duration); people with specific training contracts.

Temporary contracts might provide an entry point into the labour market, for example for people with little or no experience, the unemployed or people trying to return to work after a period outside the labour market. Some people may choose to work under temporary contracts for a number of reasons, for example to gain a variety of different experiences or to accommodate particular personal or family circumstances; temporary contracts may offer greater flexibility which may be appreciated by some employees. However, depending on national regulations, people working on temporary contracts might receive conditions different from those given to permanent workers (for example with respect to financial benefits and/or training), which, along with the generally less secure nature of temporary contracts, may affect a person’s quality of life.

Around one in seven (13.4 %) working-age employees (15-64 years) in the EU worked under temporary contracts in 2020 and around 1 in 12 (6.8 %) were employees who worked under temporary contracts because they could not find a permanent job. In other words, more than half of all workers with temporary contracts (50.7 %) could not find work with a permanent contract and so their temporary working status can be considered to be involuntary.

The share of employees who worked under a temporary contract because they could not find a permanent job is shown in Map 1. This share ranged from 0.3 % in Estonia (low reliability) to 19.5 % in Spain. Shares of more than 10 % were recorded in several southern European Member States, e.g. Portugal (14.6 %), Cyprus (12.8 %), Croatia (12.2 %) and Italy (12.1 %). On the contrary, in 16 Member States less than 5 % were involuntarily temporary employees, with four countries reporting values of less than 1 %: Germany, Lithuania (both at 0.7 %), Austria (0.6 %) and Estonia (0.3 %). Among the EFTA countries shown in the map, Iceland and Switzerland reported relatively low figures for this indicator. By contrast, among the candidate countries more than a quarter (28.0 %) of employees in Montenegro worked under a temporary contract because they could not find a permanent job.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_etgar)

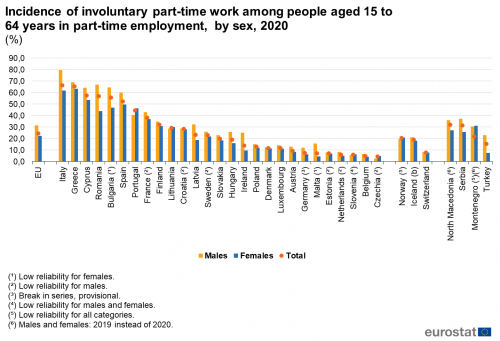

Involuntary part-time employment

Involuntary part-time employment (as a proportion of total part-time employment) measures one aspect of underemployment which is important in the context of quality of life. If people work fewer hours than they would like to, this has implications for their opportunities to earn income, interact socially, shape their identity and develop their skills, all of which can impinge on their quality of life. People sometimes accept part-time work for lack of full-time alternatives. However, in some EU Member States without favourable legislation or collective agreements for this type of contract, part-time work may be accompanied by inferior conditions as regards access to benefits and opportunities for training and career advancement.

In 2020, about one in four (24.4 %) of all part-time workers in the EU would have preferred to work full time, i.e. were in this situation involuntarily (see Figure 5). Greece and Italy were the EU Member States with the highest proportions (more than 60 %) of involuntary part-timer workers, followed by Cyprus, Romania, Bulgaria and Spain where more than half of all part-time workers would prefer to work full time. Eight Member States, Austria, Germany, Malta, Estonia, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Belgium and Czechia, recorded involuntary part-time work rates below 10 %, with Czechia at the bottom of the list at 4.5 %.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_eppgai)

At EU level, among males 31.5 % were involuntarily part-time working, among female part-time employed, the proportion was 22.2 %. In the majority of the EU Member States, the proportion of involuntary part-time workers was higher among men than among women. However, this was not the case in all countries: in Portugal, the incidence of involuntary part-time work was 5.8 percentage points higher for women than for men, with smaller gaps — but still with higher rates for women — also recorded in Czechia, Lithuania and Slovenia. The opposite situation was encountered in the other Member States, with the biggest differences recorded in Romania (23.1 percentage points), Italy (17.9 pp) and Bulgaria (17.7 pp).

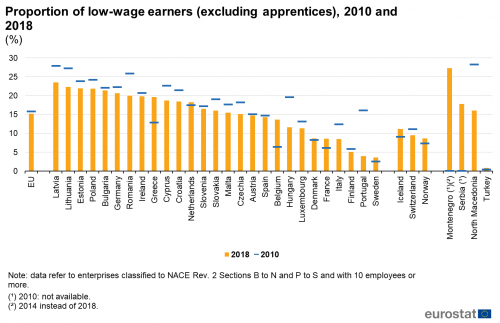

Income and benefits

Low-wage earners are employees earning two thirds or less of national median earnings (an hourly rate that one half of a country’s population earn less than and the other half earns more than). Hence, the low-wage threshold is different in each country.

In 2018 (latest available data), 15.2 % of all employees (excluding apprentices) in the EU were low-wage earners (see Figure 5). The EU Member States with the highest proportions of low-wage earners were in the Baltic Member States, eastern parts of the EU and Germany: Latvia (23.5 %), Lithuania (22.3 %), Estonia (22.0 %), Poland (21.9 %), Bulgaria (21.4 %), Germany (20.7 %) and Romania (20.0 %). At the other end of the ranking, just 3.6 % of employees (excluding apprentices) were low-wage earners in Sweden, while in Portugal, Finland, Italy, France and Denmark less than 1 in 10 employees were low-wage earners.

Between 2010 and 2018 there was a slight decrease in the share of low-wage earners in the EU, down 0.6 points from 15.8 %. The largest increase in the share of low-wage earners was in Belgium, where it rose 7.3 percentage points from 6.4 % to 13.7 %, considerably more than in any other EU Member State except Greece, where an increase of 6.8 percentage points was recorded. The largest falls in the share of low-wage earners between 2010 and 2018 were in Portugal (12.1 percentage points) and Hungary (7.9 percentage points).

(excluding apprentices), 2010 and 2018

(%)

Source: Eurostat (earn_ses_pub1a)

Over-qualified employees

For an individual, working in a job that requires a lower qualification than they possess can have an important negative impact on self-esteem, job satisfaction and their overall quality of life. Working in such a job, also usually implies a lower income. For society as a whole, over-qualified employees imply a suboptimal usage of the stock of human capital, which can hamper social and economic development. The indicator used here defines overqualified employees as those with tertiary education which work in a job classified as clerical or manual work.

Overall in the EU, about 21.5 % of working staff are over-qualified for the job they are doing. The biggest gap between individual skills and requirements for the job was observed in Spain where more than a third of the work force (35.8 %) were over-qualified, followed by Cyprus and Greece with levels above 30 %. Eight Member States recorded over-qualification rates between 20 and 30 %. All other EU countries had rates between 10 and 20 % with the exception of Luxembourg where the mismatch between skills and job requirements was just 3.9 %, the only country with a single digit value.

The three EFTA countries saw over-qualification rates between 10 and 20 %. Among the candidate countries, Turkey had the highest level of people over-qualified for their job, at 35.3 %.

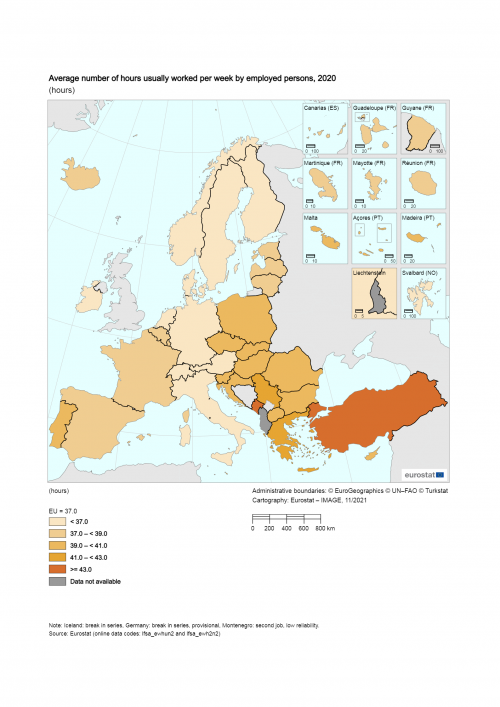

Working hours

The number of hours worked per week may affect an individual’s work-private life balance, which in turn can have an effect on subjective well-being; however, this effect is not linear. Research has shown that subjective well-being increases with the number of hours an individual works per week up to a certain point, beyond which it starts to deteriorate, possibly because excessive (for example over 48 hours per week) working hours reduce job satisfaction which in turn reduces overall fulfilment (Abdallah, Stoll and Eiffe, 2013).

In 2020, the average number of hours usually worked per week by employed persons in the EU was 37.0 for the main job (see Map 2) and 11.8 for the second job. It should be noted that the proportion of employed persons with a second job varies considerably across the EU Member States (and is relatively uncommon in most of them).

(hours)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_ipga)

Among the EU Member States, Greece had the highest average number of hours usually worked by workers in their main job, 41.8 hours per week; Turkey recorded an even longer average working week (44.5 hours). The next longest working weeks among the Member States were in Bulgaria (40.4 hours) and Poland (40.1). The lowest value was reported in the Netherlands (30.3 hours), where part-time work is very widespread. For second jobs, again Greece had the longest weekly working time, 17.3 hours per week, followed by Poland (16.5 hours) and Bulgaria (16.2 hours). At the other end of the ranking was Germany, with an average of 8.2 hours per week, the only Member State below 10.0 hours.

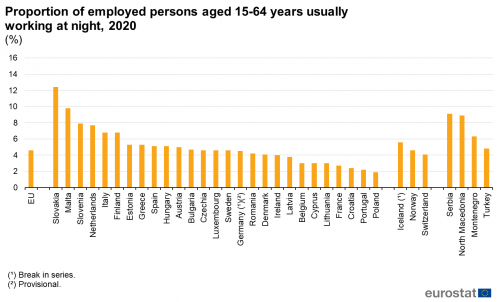

Working nights

Another indicator that may affect people's work-private life balance and thus potentially impinge on their quality of life, is the proportion of persons employed usually working at night. In 2020, an average of 4.6 % of employed people aged 15-64 years in the EU usually worked at night (see Figure 8). The distribution across EU Member States varied between 1.9 % in Poland and 9.8 % in Malta, with the share in Slovakia (12.4 %) much higher than anywhere else in the EU, reflecting in particular the extensive use of night shifts in Slovakia's relatively large manufacturing sector. Among the candidate countries, Serbia and North Macedonia also reported relatively high shares of persons employed working at night, 9.1 % and 8.9 %, respectively; in Turkey the share was 4.8 %, lower than in eleven Member States.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_ewpnig)

Health and safety at work

An important indicator that may be used to assess the quality of employment is the rate of accidents at work. This is measured by the number of work accidents recorded during a year per 100 000 persons employed. The information is presented as standardised rates that reflect the structure of the economy, as some activities (such as mining and quarrying or construction) have much higher incidence rates of accidents than others and the economic structure differs between EU Member States. The incidence of accidents at work reflects among other things, the extent to which health and safety standards are upheld in the workplace.

The following data refers to fatal accidents as these are better recorded than non-fatal accidents due to their severity and therefore they are more comparable between Member States. It should be noted that the total number of fatalities at work is relatively low and so the incidence rate can vary greatly from one year to the next, particularly in some of the smaller Member States.

(number per 100 000 persons employed)

Source: Eurostat (hsw_mi01)

In 2018, the EU incidence rate for fatal accidents at work was 2.2 per 100 000 persons employed, down slightly from 2.9 per 100 000 persons employed, recorded in 2010 (see Figure 9). The incidence rate in Luxembourg was almost three times as high as the EU average, at 6.4 per 100 000 persons employed, with the next highest rates at 5.3 in Romania and 4.7 in Latvia. The Netherlands had the lowest incidence of fatal work-related accidents in 2018, 0.9 per 100 000 persons employed, followed by Germany (at 1.0). Finland, Sweden, Greece, Poland, Denmark and Estonia had rates below 2.0 fatal accidents per 100 000 persons employed.

The biggest increase in fatal accidents at work was recorded in Latvia (up 1.2 per 100 000) and Luxembourg (plus 1.1). The largest decrease was seen in Portugal (minus 2.6 per 100 000), Cyprus (minus 2.3) and Poland (down 2.2)

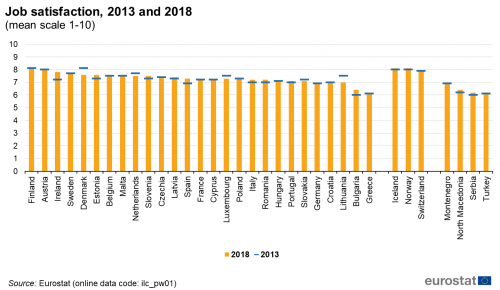

Job satisfaction

Empirical research suggests that job satisfaction is one of the most important factors in and predictors of overall life satisfaction. The results of the European quality of life surveys show that the satisfaction of people in employment with their current job appears to be relatively uniform across the EU Member States, as in 2018 average satisfaction was rated between 7.0 and 8.1 (on a mean scale of 1 to 10) in nearly all cases — see Figure 10. There were two exceptions, namely Bulgaria and Greece where job satisfaction was recorded at 6.4 and 6.2 respectively. Between 2013 and 2018 the mean level of job satisfaction changed by +/-0.4 points or less in most Member States, with a larger decrease in Lithuania and Denmark (down 0.5 points) and a larger increase in Ireland (up 0.6 points). Among the candidate countries shown in Figure 10 relatively small changes in job satisfaction were observed.

While job satisfaction depends on a multitude of factors (such as job content, responsibility, motivation, perception of fairness in the workplace, or remuneration), low job satisfaction and other adverse factors often coexist. For example, the EU Member State at the bottom of the job satisfaction scale, Greece, also reported the highest level of unemployment (see Figure 2) and of involuntary part-time employment (see Figure 5) and the highest number of hours worked by full-time workers in their main job (see Map 2). Furthermore, Lithuania registered the third lowest job satisfaction and the second highest proportion of low-wage earners (see Figure 6).

At the top end of the job satisfaction scale the relationship to a relative absence of adverse factors is less clear cut. Finland, Austria, and Ireland exhibited middle rankings for several of the adverse factors referred to above, with low rankings for Finland concerning the proportion of low-wage earners (see Figure 6) and the number of hours worked by full-time workers in their main job (see Map 2). Interestingly, Austria reported the second highest job satisfaction combined with the fifth highest incidence of fatal accidents at work, although it did report a particularly low share of employees who were unable to find a permanent contract (see Map 1).

Other main activity: proportion of the inactive population

People are considered as economically inactive if they are not part of the labour force, in other words they are neither employed nor unemployed. Provided that they are not in gainful employment and not available or looking for work either, among the working-age population the economically inactive population includes students, people caring for family members (often housewives or househusbands), some pensioners (where retirement before 65 is possible or for reasons of disability), as well as others who are not in the labour market for a variety of reasons, for example due to health reasons or because they have chosen to travel or undertake unpaid voluntary work. In general, many economically inactive people (like economically active people) do unpaid work that is valuable from an individual as well a societal perspective. Each subgroup of the economically inactive population has its own characteristics and issues that influence their quality of life.

The data presented in Figure 11 show the proportion of the population that was economically inactive before and during the pandemic; this can be compared with the employment rates presented in Figure 1 which are also shown as a proportion of the population for those years.

In 2020, just over one quarter (27.1 %) of the population aged 15-64 years in the EU was economically inactive, overall 0.5 percentage points more than in 2019. The lowest proportions of economically inactive people were reported in the Nordic Member States, as well as several western parts of the EU — the Netherlands and Germany. There were twelve Member States where the proportion of economically inactive persons was under one quarter. The three EFTA countries included in Figure 11 also reported relatively low proportions of economically inactive people. At the other end of the ranking, in excess of 30.0 % of the working-age population were economically inactive in Romania, Belgium, Greece, Croatia and Italy — and this was also the case in all the candidate countries included in Figure 11.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_ipga)

Between 2019 and 2020, the share of the working-age population that was economically inactive in the EU rose by 0.5 percentage points. In most (15 out of 27) Member States the share of economically inactive persons increased. The same is true for the EFTA and candidate countries. Among the EU Member States, the largest increases in the share of economically inactive amongst the working-age population were in Italy and Spain (1.6 percentage points) and Ireland (1.4 percentage points). Among the candidate countries Montenegro (+4.7 percentage points) recorded by far the largest increase. On the other hand, there were slight decreases in 9 Member States, the largest being recorded in Malta (-1.2 percentage points).

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

In the context of quality of life, the term ‘productive or main activity’ covers quantitative and qualitative aspects of employment and the main activity of those not in employment.

- Data on the quantity (or lack of) employment are provided by indicators on employment, unemployment (unemployment rate and long-term unemployment rate) and underemployment (involuntary part-time employment). All data on these quantitative aspects of employment come from the EU’s Labour force survey (LFS), a continuous household survey carried out in all EU Member States, EFTA countries (except Liechtenstein) and candidate countries.

- Data on the quality of employment relate to several aspects of work, such as income and benefits (measured by the percentage of low-wage earners, which is derived from the structure of earnings survey (SES)), health and safety at work (work-related accidents from European Statistics on Accidents at work). Information on the work-private life balance (average number of hours usually worked per week; prevalence of night work), the prevalence of temporary contracts and over-qualification among the workforce, is coming from the EU-LFS. Self-assessment of the quality of employment complements the objective indicators. An indicator on job satisfaction is available from the 2013 EU SILC ad hoc module, which was repeated in 2018.

Context

The European Pillar of Social Rights is the EU’s overarching strategy for inclusive growth (which includes more and better jobs) for the current decade. The Pillar sets out 20 key principles which represent the beacon guiding us towards a strong social Europe that is fair, inclusive and full of opportunity in the 21st century. One of the three targets included in the strategy relates to employment, as 78 % of people aged 20-64 should be in work by 2030. As well as this target linked directly to the quantity of employment, other targets within the strategy are also linked to employment. For example, reducing the number of early leavers from education and training, or increasing the proportion of people having completed at least a medium level of education may boost employment rates.

The European employment strategy (EES) was launched in 1997 in anticipation of the entry into force of the Amsterdam Treaty. The EES established a framework to encourage EU Member States to put into place effective policies. Overall, the main aim of the strategy is the creation of more and better jobs throughout the EU. The EES now constitutes part of the Europe 2020 growth strategy and it is implemented through the European semester, an annual process promoting close policy coordination among Member States and EU institutions. The implementation of the EES involves the following four steps of the European semester:

- Employment guidelines are common priorities and targets for employment policies proposed by the European Commission, agreed by national governments and adopted by the EU Council.

- The Joint employment report (JER) is based on (a) the assessment of the employment situation in the EU (b) the implementation of the employment guidelines and (c) an assessment of the scoreboard of key employment and social indicators. It is published by the European Commission and adopted by the EU Council.

- National Reform Programmes (NRPs) are submitted by national governments and analysed by the European Commission for compliance with Europe 2020.

- Based on an assessment of the NRPs, the European Commission publishes a series of country reports, analysing Member States’ economic policies and issues country-specific recommendations.

The current employment guidelines target four key domains and are structured as follows:

- boosting demand for labour, and in particular guidance on job creation, labour taxation and wage-setting;

- enhanced labour and skills supply, by addressing structural weaknesses in education and training systems, and by tackling youth and long-term unemployment;

- better functioning of the labour markets, with a specific focus on reducing labour market segmentation and improving active labour market measures and labour market mobility;

- fairness, combating poverty and promoting equal opportunities for all.

Direct access to

- All articles on the labour market

- Quality of life indicators (online publication)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (t_lfsa)

- Employment rate by educational attainment level (tepsr_wc120)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- Employment rates - LFS series (lfsa_emprt)

- Temporary employment - LFS series (lfsa_emptemp)

- Full-time and part-time employment - LFS series (lfsa_empftpt)

- Population in employment working during unsocial hours - LFS series (lfsa_empasoc)

- Working time - LFS series (lfsa_wrktime)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- Inactivity - LFS series (lfsa_inac)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (lfso)

- 2014. Migration and labour market (lfso_14)

- Labour market situation of immigrants (lfso_14lmk)

- Self-declared over-qualified employees as percentage of the total employees by sex, age, migration status and educational attainment level (lfso_14loq)

- Labour market situation of immigrants (lfso_14lmk)

- 2014. Migration and labour market (lfso_14)

- Accidents at work (ESAW, 2008 onwards) (hsw_acc_work)

- Earnings, see:

- Structure of earnings survey - main indicators (earn_ses_main)

- Low-wage earners and median earnings (earn_ses_pub)

- Proportion of low-wage earners (earn_ses_pub1)

- Low-wage earners as a proportion of all employees (excluding apprentices) by age (earn_ses_pub1a)

- Proportion of low-wage earners (earn_ses_pub1)

- Low-wage earners and median earnings (earn_ses_pub)