Archive:Housing conditions

- Data from July 2014. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database.

This article analyses recent statistics on housing conditions in the European Union (EU). One of the key challenges of Europe 2020 and in particular the poverty and social exclusion element, is to provide decent (in terms of quality and cost) housing for everyone. The cost and quality of housing is key to living standards and well-being; shortage of adequate housing is a long-standing problem in most European countries. Over the past decade, worsening affordability, homelessness, social and housing polarisation and new forms of housing deprivation have been an increasing concern for public policy.

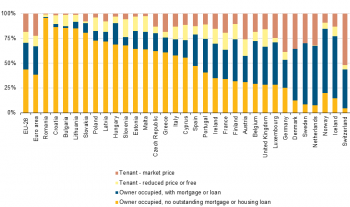

(% of population) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho01)

(% of population) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho02)

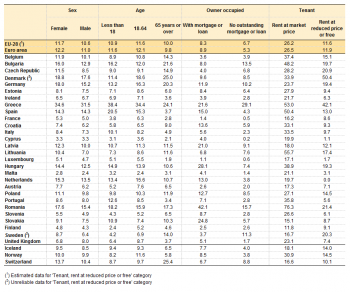

(% of specified population) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho07a) and (ilc_lvho07c)

(% of specified population) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho05a) and (ilc_lvho06)

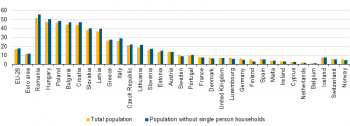

(% of specified population) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho05a)

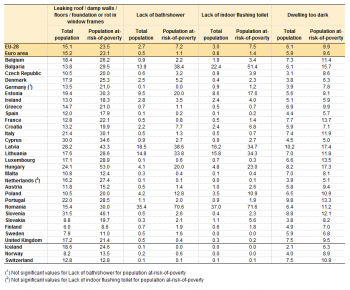

(% of specified population) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdho01), (ilc_mdho02), (ilc_mdho03) and (ilc_mdho04)

(% of specified population) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdho06a)

(% of specified population) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddw01), (ilc_mddw02) and (ilc_mddw03)

Main statistical findings

Type of dwelling and tenure status

In 2012, 41.3 % of the EU-28 population lived in flats, just over one third (34.1 %) in detached houses and 24.0 % in semi-detached houses. The share of persons living in flats was highest among the EU Member States in Estonia (65.1 %), Spain (65.0 %) and Latvia (64.4 %). The share of people living in detached houses peaked in Croatia (73.0 %), Slovenia (66.6 %), Hungary (63.9 %) and Romania (60.5 %); Norway also reported high share (60.7 %) of their population living in detached houses. The highest propensity to live in semi-detached houses was reported in the United Kingdom (60.9 %), the Netherlands (60.0 %) as well as Ireland (59.0 %) – see Figure 1.

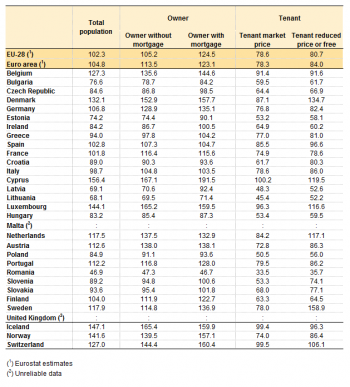

In 2012, over one quarter (27.1 %) of the EU-28 population lived in an owner-occupied home with mortgage or loan while almost half (43.5 %) of the population lived in an owner-occupied home with no outstanding mortgage or housing loan (Figure 2). As such, just over seven out of every ten (70.6 %) persons in the EU-28 lived in owner-occupied dwellings, while 18.4 % were tenants with a market price rent, and 11.0 % tenants in reduced-rent or free accommodation.

More than half of the population in each EU Member State (see Figure 2) lived in owner-occupied dwellings in 2012; the share ranged from 53.2 % in Germany to 96.6 % in Romania. In Switzerland, people living in rented dwellings outweighed those living in owner-occupied dwellings (56.2 % of the population are tenants). In Sweden (61.6 %), the Netherlands (59.9 %) and Denmark (51.8 %) more than half of the population lived in owner-occupied dwellings with mortgage or loan; this was also the case in Norway (64.9 %) and Iceland (62.7 %).

The share of persons living in rented dwellings with a market price rent in 2012 was less than 10.0 % in 11 EU Member States. In Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and Austria more than one quarter of the population lived in rented dwellings with a market price rent; this share rose to slightly more than half (51.7 %) in Switzerland. The share of the population living in a dwelling with a reduced price rent or occupying a dwelling free of charge was less than 20.0 % in all Member States.

Housing affordability

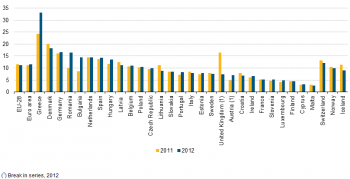

In 2012, 11.2 % of the EU-28 population lived in households that spent more than 40 % of their disposable income on housing (see Figure 3). In Greece, Denmark, Germany, Romania, Bulgaria, the Netherlands and Spain the housing cost overburden rate exceeded 14.0 % while the lowest rates were reported by Cyprus (3.3 %) and Malta (2.6 %).

Between 2011 and 2012, the housing cost overburden rate in the EU-28 decreased by 0.4 pp. In total, nine Member States reported for 2012 decreases, as compared to 2011, ranging from 0.1 pp in the Netherlands, to 9 pp in the United Kingdom (although for the latter this might be, at least partially, attributed to the reported series break in 2012). Iceland, Norway and Switzerland also reported decreases in respective housing cost overburden rates for 2012, as compared to the previous year. In two Member States, namely Slovakia and France, the rates remained stable. On the other hand, the largest increases were reported in Greece (an increase of 8.9 pp), Romania (an increase of 6.6 pp) and Bulgaria (an increase of 5.8 pp).

Housing affordability varies between different groups of society. Overall women were found to be more vulnerable to housing cost overburden than men in all, with the exception of the United Kingdom and Ireland (Table 1). This trend is especially evident in Lithuania, where overburden rates were 3.4 pp higher for women than for men, as well as in Bulgaria, Greece, the Czech Republic and Germany where differences were greater than 2.5 pp. Large differences have also been reported in Switzerland (3.3 pp). No clear trend is apparent in terms of a person's age with regard to housing affordability; at EU-28 level the percentage of people whose housing costs exceeded 40 % of their equivalised disposable income was around 11.0 % for people below the age of 18, 11.6 % for people in the age of 18-64 and 10.0 % for people over the age of 65. However, this is not the same in all EU Member States. In eleven Member States the elderly suffer more than the younger age groups in what regards housing cost affordability. The greatest difference in the housing cost overburden rate between the 18-64 age group and the elderly (over the age of 65) was reported in Bulgaria, Sweden and Denmark (which reported differences of 9.6, 7.1 and 6.4 pp respectively) and also in Switzerland (which reported a difference of 15.7 pp). On the other hand, the largest difference for those countries where the younger group (18-64) suffers more than the elderly (+65) was reported by Spain (11.6 pp) and Greece (10.3 pp).

The proportion of the population whose housing costs exceeded 40 % of their equivalised disposable income was higher for owners with a mortgage or loan than those owners that had no outstanding mortgage or housing loan, with the exceptions of Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Greece, Lithuania, Finland and Sweden. The same exception holds for Switzerland. For tenants, higher overburden rates tend to apply to those tenants that pay their rent at the market price. The only exceptions here apply to Denmark and Sweden; however this finding should be treated with caution due to low reliability of the value for those renting at reduced price or free.

Housing quality - overcrowding

One major element of the quality of housing conditions is the availability of sufficient space in the dwelling. The indicator that has been invented to describe space problems is the overcrowding rate, which assesses the proportion of people living in an overcrowded dwelling, as defined by the number of rooms available to the household, the household’s size, as well as its members’ ages and family situation. In 2012, the highest rates of overcrowding (Figure 4) were observed in Romania (51.6 %), Hungary (47.2 %) and Poland (46.3 %), while the lowest were seen in Cyprus (2.8 %), the Netherlands (2.5 %) and Belgium (1.6 %). The EU-28 average rate of overcrowding was 17.0 %.

In the EU as a whole and in more than half of the EU countries the overcrowding rate is higher if single person households are excluded from the computation of the indicator (see Figure 4). On the other hand in Sweden, France, Denmark, Luxembourg, Germany, Finland, the Netherlands, Belgium as well as in Iceland, Switzerland, and Norway the exclusion of single-person households decreases the overcrowding rate (e.g. very small flats - studios are inhabited by one person). However, in these countries overcrowding rates are relatively low.

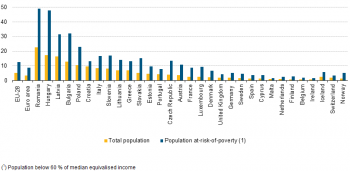

Overall in the EU-28 (Figure 5), the overcrowding rate is higher for those who are at risk-of-poverty (i.e. people living in households where equivalised disposable income per person was below 60 % of the national median) compared to the total population. The greatest differences in the overcrowding rates between the two groups were observed in Hungary (a difference of 23.8 pp), the Czech Republic (a difference of 22.4 pp), Sweden (a difference of 21.3 pp) and Austria (a difference of 20.4 pp). Also Norway reported a large difference (17.8 pp). On the other hand, the smallest differences were observed in Croatia, Malta and Ireland (each with percentage difference of lower than 4 pp).

Apart from the overcrowding rate, other measures, such as the size of the dwelling, can also provide a representative picture of housing quality, in terms of the availability of sufficient useful space in the dwelling. In 2012, the average size of the dwelling at EU-28 level was 102.3 m2. The average useful floor area of a dwelling varied in size from 46.9 m2 in Romania, 68.1 m2 in Lithuania and 69.1 m2 in Latvia up to 156.4 m2 in Cyprus (Table 2).

Overall, in 2012, owners with a mortgage or loan lived in dwellings whose size was on average 124.5 m2, while owners with no outstanding mortgage or housing loan had on average less living space at their disposal (105.2 m2). Among homeowners, this pattern is evident in the majority of Member States, except for Luxembourg, the Netherlands, France, Spain, Italy and Romania. The same exception holds for Iceland.

On the other hand, Europeans living in rented dwellings had, on average, less useful floor area at their disposal compared to homeowners. Europeans living in dwellings with a market price rent reported an average size of 78.6 m2 for their dwelling, while those living in dwellings with a reduced price or free of charge reported an average size of 80.7 m2.

Dwellings rented at market price varied in size across Member States. In Romania, Lithuania and Latvia, rented dwellings at market price were relatively small (less than 50 m2), while in the Netherlands, Spain, Denmark, Belgium and Luxembourg, the usable floor in dwellings rented at market price exceeded 80 m2, peaking at 100.2 m2 in Cyprus. Tenants living in dwellings with a reduced price or free of charge had relatively more usable floor space at their disposal. The available floor space for tenants living in dwelling with a reduced price or free of charge exceeded 100.0 m2 in Sweden, Denmark, Cyprus, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

Housing quality – housing deprivation

Housing quality can also be assessed by looking at other housing deficiencies, such as lack of certain basic sanitary facilities in the dwelling (such as a bath or shower or indoor flushing toilet), problems in the general condition of the dwelling (leaking roof or dwelling being too dark). In 2012 (Figure 6), 79.5 % of the Europeans (EU-28 average) were declared as not deprived for the 'housing dimension', 15.5 % were found to suffer from one of the dwelling problems, 4.0 % suffered from two, 0.8 % suffered from three and 0.2 % suffered from all four of dwelling problems (i.e. leaking roof/damp walls/floors/foundation or rot in window frames AND accommodation being too dark AND no bath/shower AND no indoor flushing toilet for sole use of the household).

At the EU-level, the main housing problem was found to be a ‘leaking roof’ (i.e. leaking roof or damp walls, floors or foundation, or rot in window frames of floor') (15.1 %), followed by ‘darkness of the dwelling' (6.1 %) while around 3.0 % of the EU population lacked basic sanitary facilities (i.e. lack of bath/shower or indoor flushing toilet) (Table 3). Exceptions to this EU trend are Bulgaria, Lithuania and Romania, where sanitary problems were found to be more frequent than the other two housing problems mentioned above. In Sweden and the Netherlands, nobody was reported to be lacking indoor flushing toilet. At the other extreme, about 36.2 % of the people in Romania had no bath or shower, or no indoor flushing toilet (35.4 % and 37.0 % respectively).

Overall, people at-risk-of poverty suffered more than the total population from these certain housing problems (or were deprived to a greater extent than the total population for the particular items). This was particularly the case in Romania, where the deficiency of basic sanitary facilities was found to be extremely common; 70.6 % of the at-risk-of poverty population were found not to have a bath or shower and 71.6 % did not have indoor flushing toilet. The situation is somewhat better, but still bad, in Bulgaria where 51.4 % of the at-risk-of-poverty population were found to be lacking indoor flushing toilet and 38.4 % of the at-risk-of-poverty population were found to be lacking a bath or shower. In Hungary, more than half of the at-risk-of-poverty population suffered from a ‘leaking roof’.

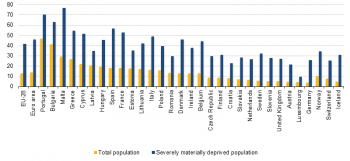

Insufficient spacing and poor amenities are those characteristics used to define severe housing deprivation. In 2012, the severe housing deprivation rate in the EU was 5.1 % and it was more than double that figure (12.6 %) for the population that was at risk of poverty (Figure 7). The highest rates for the total population were exhibited by Romania (22.8 %), Hungary (17.2 %) and Latvia (16.4 %). The severe housing deprivation rate was below 1 % of the total population in the Netherlands, Finland, Belgium and Ireland. In Romania and Hungary almost half of the population that was at-risk-of poverty faced severe housing deprivation (49.2 % and 48.0 % respectively).

The severe housing deprivation rate was from 1.4 to 3.9 times (for the EU-28 it is 2.5 times) greater for the population at-risk-of poverty compared to the total population. The discrepancy is even larger in Norway, where the rate was found to be 4.3 times greater for the at-risk-of-poverty population.

In addition to objective measures of housing deprivation, indicators reflecting people’s perceptions of the sufficiency of the facilities of their dwelling to satisfy the general needs of the household can also be used to assess housing deficiencies. Below we analyse self-reported measures of the efficiency of the dwelling equipment in terms of insulation and heating / cooling system.

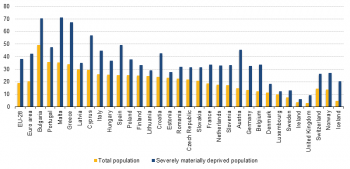

In 2012, 12.9 % of the EU-28 population declared that their dwelling was not comfortably warm during winter (Figure 8). The share of the population living in a dwelling not comfortably warm during winter did not exceed 30.0 % in all EU countries, except for Portugal (46.6 %) and Bulgaria (41.1 %). On the other hand, almost 20.0 % of the Europeans perceived the dwelling not sufficiently insulated against excessive heat during summer (Figure 9); the share ranged from 3.3 % in the United Kingdom, to at least 30.0 % in Greece, Malta and Portugal, and peaking at 49.5 % in Bulgaria.

Overall, people assessed to be severely materially deprived were more likely to face heating and cooling problems in the dwelling during winter and summer than the total population reporting the same problems. This is particularly evident in Malta (Figures 8 and 9), where such problems were reported by a significant percentage of the population; 76.7 % of the severely materially deprived population felt their dwelling insufficiently warm during winter and 71.3 % of the same population declared that their dwelling was not comfortably cool during summer.

Moreover, in Malta, Portugal, Bulgaria, Spain, Greece, France and Cyprus, more than half of the severely deprived population found the heating system unable to keep their dwelling adequately warm during winter; while more than two thirds of the population in Greece, Bulgaria and Malta perceived that the dwelling was not kept efficiently cool during summer.

Housing quality – problems in the residential area

Housing quality depends not only on the quality of the dwelling itself, but also on the wider residential area. In this case the indicators rely on the subjective opinion of the respondents, but have the advantage of drawing a more complete picture of housing.

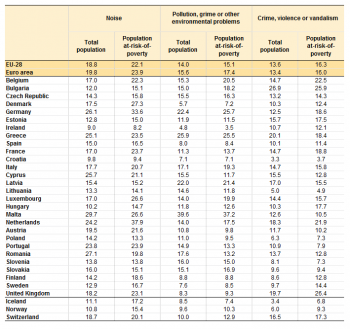

In 2012, 18.8 % of EU-28 population lived in a dwelling where noise from neighbours or from the street was perceived as a problem (Table 4). Almost 30.0 % of people in Malta were concerned with noise, followed by Romania (27.1 %), Germany (26.1 %), Cyprus (25.7 %) and Greece (25.1 %). At the other extreme, the rates were lowest in Hungary (10.2 %), Croatia (9.8 %) and Ireland (9.0 %). The same holds for Iceland (11.1 %) and Norway (10.8 %).

In 2012, 14.0 % of the EU-28 population perceived the area in which they live as being affected by pollution, grime or other environmental problems. At the country level, the figures ranged from less than 10 % in Finland, the United Kingdom, Spain, Sweden, Croatia, Denmark and Ireland to almost 40.0 % in Malta. Rates were also small in Switzerland (10.0 %), Norway (9.6 %) and Iceland (8.5 %).

Crime and/or vandalism were perceived as a problem by 13.6 % of the EU-28 population in 2012. At the country level, the rates were highest in Bulgaria (26.9 %) and Greece (20.1 %), while only 3.3 % of the population in Croatia and 5.0 % in Lithuania considered this to be a problem. Rates were also low for Iceland (3.4 %) and Norway (6.0 %).

Additionally, access of basic services is another an important determinant for assessing housing quality in the residential area. Accessibility to basic facilities in the residential area, such as public transport and health care services, refers to the ability of households to obtain the services they need.

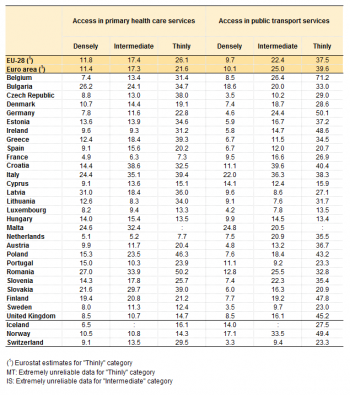

In 2012, the share of the EU-28 population considering that primary health care services could be accessed with some or great difficulty peaked at 26.1 % in thinly populated areas of the EU (Table 5), which was considerably higher than the respective shares recorded for either intermediate density areas (17.4 %) or densely populated areas (11.8 %).

This pattern was common across all EU Member States in 2012, although there were some exceptions. In Croatia, the highest share of the population reporting some or great difficulty in accessing primary health care services was recorded for intermediate density areas.

By contrast, the largest differences between the population having some or great difficulty in accessing primary health care services in thinly and densely populated areas, were recorded in Poland, the Czech Republic and Greece, where thinly populated areas recorded a share that was over 25 pp higher than for densely populated areas.

Slightly less than 40.0 % of the EU-28 population (Table 5) in thinly populated areas considered that there was some or great difficulty in accessing transport services in 2012, with this share ranging from 13.4 % in Hungary to 71.2 % in Belgium. On the other hand, the same share for intermediate density areas was 15.1 pp (22.4 %) lower than for thinly populated areas.

In all Member States, the proportion of the population reporting some or great difficulty in accessing public transport was lower (an average of 9.7 % across the whole of the EU-28) for densely population areas than the other area types. Exceptions to this trend are Cyprus, Portugal, Latvia and Lithuania.

Finally, differences between the population having some or great difficulty in accessing transport services in thinly and densely populated areas exceeded 40.0 % in Belgium, Germany, Ireland and Finland.

Overall satisfaction with the dwelling

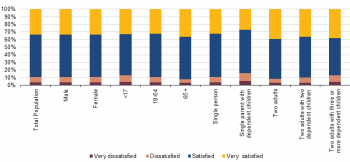

Overall, 89.3 % of Europeans in 2012 felt (very) satisfied with the dwelling they lived in. Subjective assessments of Europeans of the degree of their satisfaction with the dwelling were based on a number of factors considered important for meeting household needs, such as the price, space and quality of the dwelling, distance from home to work, etc.

Figure 10 explores the relation of some socio-demographic characteristics (sex, age, and household composition) with the degree of satisfaction of with the dwelling. Evidently sex is not a factor that is related to the degree that the person feels satisfied with the dwelling, since percentages for both males and females are similar.

Regarding the age dimension, the differences between the three age groups (less than 17 years old, 18 to 64 years old and over than 65 years old) are small, however respondents aged 65 and over felt very satisfied with their dwelling at a higher frequency than respondents in the two other age groups. Differences are as high as 3.0 pp between the population aged 65 and over and the population less than 17 years, and 3.6 pp between the population aged over 65 years and the younger age group.

The degree of satisfaction with the dwelling seems to be also affected by the household composition. Single parents with dependent children reported the highest percentage of dissatisfaction with their dwelling (16.0 %) compared with households with two adults with or without dependent children.

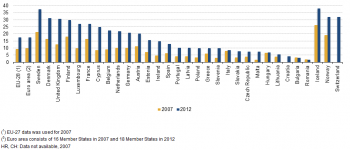

Although the majority of Europeans felt (very) satisfied with their dwelling in 2012, slightly more than one in six persons reported that has changed dwelling during the last five years (Figure 11). At country level, the highest percentage of population having changed dwelling within a five-year period was recorded in Sweden (37.6 %), followed by Denmark (31.3 %) and the United Kingdom (30.8 %). Between 2007 and 2012, the percentage of population that moved to other dwelling increased by 8.4 pp. Τhe largest differences were recorded in the United Kingdom (18.1 pp), Luxembourg (17.4 pp), Cyprus (16.6 pp) and Sweden (16.3 pp). Only Romania and Bulgaria reported decreases in their respective percentages (a decrease of 0.3 and 0.2 pp respectively).

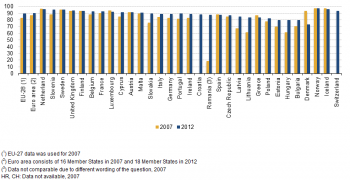

Overall, the percentage of population feeling satisfied or very satisfied with the dwelling increased in 2012 compared to 2007 (Figure 12). Between 2007 and 2012, the proportion of population declaring (very) satisfied with the dwelling increased by at least 15 pp in Latvia, Hungary, Lithuania and Romania, although for the latter this could be due to the reported difference in the wording of the question in 2007. In total, six countries reported decreases between 2007 and 2012, ranging from 0.1 pp in Sweden to 19.9 pp in Denmark. The same holds for Norway and Iceland.

Data sources and availability

The data used in this section are primarily derived from micro-data from EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). The reference population is all private households and their current members residing in the territory of the Member State at the time of data collection; persons living in collective households and in institutions are generally excluded from the target population. The EU-28 aggregate is a population-weighted average of individual national figures.

All the data used in this article related to the the space in the dwelling, dwelling installations and facilities, overall satisfaction with the dwelling, the accessibility of basic services and the reasons for having changed dwelling in the past, come from the EU-SILC 2012 ad-hoc module on housing conditions, which was firstly carried out in 2007.

Context

Questions of social housing, homelessness or integration play an important role within the EU’s social policy agenda. The charter of fundamental rights stipulates in Article IV-34 that ‘in order to combat social exclusion and poverty, the Union recognises and respects the right to social and housing assistance so as to ensure a decent existence for all those who lack sufficient resources, in accordance with Community law and national laws and practices’.

However, the EU does not have any responsibilities in respect of housing; rather, national governments develop their own housing policies. Many countries face similar challenges: for example, how to renew housing stocks, how to plan and combat urban sprawl, how to promote sustainable development, how to help young and disadvantage groups to get onto the housing market, or how to promote energy efficiency among house owners.

In order to draw a more complete picture of housing conditions, the 2012 module on housing conditions complements existing indicators derived from the core EU-SILC instrument with subjective data about people’s perceptions of their housing conditions. Additionally, the collected statistics permit analyzing the evolution of the results on this topic and in continuation of the former (2007) ad-hoc module.

See also

- European cities - demographic challenges

- Housing statistics

- Housing price statistics - house price index

- Income distribution statistics

- People at risk of poverty or social exclusion

- Statistics on European cities

- Quality of life indicators

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- European social statistics (2013)

- Housing conditions in Europe in 2009 - Statistics in focus 4/2011

- Income and living conditions in Europe - Statistical books

- The social situation in the European Union 2009 - Statistical books

- Over-indebtedness of European households in 2008 - Statistics in focus 61/2010

- 51 million young EU adults lived with their parent(s) in 2008 - Statistics in focus 50/2010

- Combating poverty and social exclusion

Main tables

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (t_ilc_ip)

- Living conditions (t_ilc_lv)

Database

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

- Housing conditions (ilc_lvho)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- Housing deprivation (ilc_mdho)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file - ilc_esms)

- The production of data on homelessness and housing deprivation in the European Union: survey and proposals

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

Other information

- Regulation 1177/2003 of 16 June 2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation 1553/2005 of 7 September 2005 amending Regulation 1177/2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation 1791/2006 of 20 November 2006 adapting certain Regulations and Decisions in the fields of ... statistics, ..., by reason of the accession of Bulgaria and Romania

External links

- Employment and Social Developments in Europe (2013)

- The Housing Sector in Europe - Household Consumption Long Term and During the Crisis - Peter Parlasca, RICS research report, October 2013

- United Nations - Housing and its environment

- WHO - Housing