Archive:Housing conditions

This article has been archived. For updated information, please see Living conditions in Europe - housing quality and Housing statistics.

This article analyses recent statistics on housing conditions in the European Union (EU). The cost and quality of housing is key to living standards and well-being; shortage of adequate housing is a long-standing problem in most European countries. Over the past decade, worsening affordability, homelessness, social and housing polarisation and new forms of housing deprivation have been an increasing concern for public policy.

(% of specified population)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho07a) and (ilc_lvho07c)

(% of specified population)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho05a) and (ilc_lvho06)

(% of specified population)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho05a)

(m2)

Source: Eurostat 2012 ad-hoc module 'Housing Conditions' (ilc_hcmh01)

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddd04b)

(% of specified population)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdho01), (ilc_mdho02), (ilc_mdho03) and (ilc_mdho04)

(% of specified population)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdho06a)

(% of specified population)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddw01), (ilc_mddw02) and (ilc_mddw03)

Main statistical findings

Housing affordability

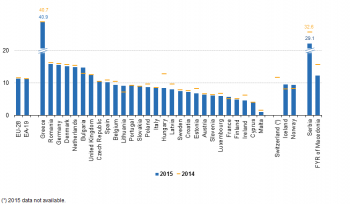

In 2015, 11.3 % of the EU-28 population lived in households that spent more than 40 % of their disposable income on housing (see Figure 1). In Greece, Romania, Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands and Bulgaria the housing cost overburden rate exceeded 14.0 %, while the lowest rates were reported by Cyprus (3.9 %) and Malta (1.1 %).

Between 2014 and 2015, the housing cost overburden rate in the EU-28 decreased by 0.2 percentage points (pp). In total, 6 EU Member States reported increases for 2015, as compared with 2014, ranging from + 0.1 pp in Slovakia and Italy, to + 2.0 pp in Lithuania. Iceland and Norway also reported an increase in respective housing cost overburden rates for 2015, as compared with the previous year. In the United Kingdom, the rates remained stable. On the other hand, the largest decreases were reported in Hungary (– 4.3 pp), Ireland (– 1.6 pp), Estonia and Latvia (both with – 1.5 pp).

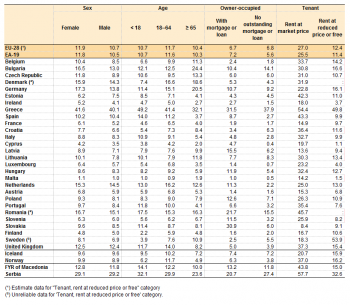

Housing affordability varies between different groups in society. Overall, women were found to be more vulnerable to housing cost overburden than men in most EU Member States, with the exception of Estonia, Spain and Finland (see Table 1). This trend was especially evident in Germany and Bulgaria, where overburden rates were 3.5 pp higher for women than for men, as well as in the Czech Republic (2.9 pp), Lithuania (2.3 pp) and Belgium (1.9 pp).

No clear trend was apparent in terms of a person’s age with regard to housing affordability; at EU-28 level the percentage of people whose housing costs exceeded 40 % of their equivalised disposable income in 2015 was 10.7 % for people under the age of 18, 11.7 % for people aged 18–64 and 10.4 % for people aged 65 or over.

However, the same cannot be said for all EU Member States. In 12 EU Member States the elderly suffered more than the younger age groups with regard to housing cost affordability with the greatest differences in the housing cost overburden rate between the 18–64 age group and the elderly (65 or over) in Bulgaria, Germany and Lithuania (which reported differences of 11.9, 5.4 and 3.9 pp respectively). On the other hand, the largest difference for those EU Member States where the younger group (18–64) suffered more than the elderly (65 or over) were observed in Greece (9.3 pp) and Spain (7.5 pp).

The proportion of the population whose housing costs exceeded 40 % of their equivalised disposable income was higher for owners with a mortgage or loan than those owners that had no outstanding mortgage or housing loan, with the exceptions of Greece, Bulgaria, Sweden, Croatia, Lithuania, Finland, Estonia and Austria. The same exception applied for the Serbia. For tenants, higher overburden rates tended to apply to those tenants that pay their rent at the market price. The only exceptions here applied to Slovakia and Sweden; however data for Sweden should be treated with caution due to low reliability of the value for those renting at reduced price or free.

Housing quality — overcrowding

One major element of the quality of housing conditions is the availability of sufficient space in the dwelling. The indicator that is used to describe space problems is the overcrowding rate, which assesses the proportion of people living in an overcrowded dwelling, as defined by the number of rooms available to the household, the household’s size, as well as its members’ ages and family situation.

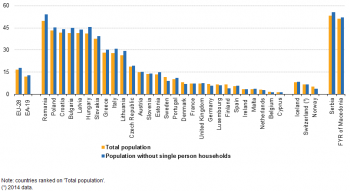

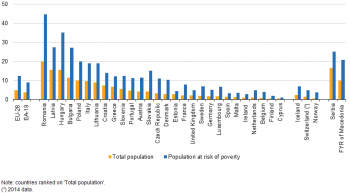

In 2015, while the EU-28 average rate of overcrowding was 16.7 % (see Figure 2), the highest rates of overcrowding were observed in Romania (49.7 %), Poland (43.4 %), Croatia, Bulgaria, Latvia and Hungary (all over 41.0 %), and the lowest in the Netherlands (3.3 %), Belgium (1.6 %) and Cyprus (1.4 %).

Overall in the EU-28 (see Figure 3), the overcrowding rate was higher for those who were at risk of poverty compared with the total population. The largest differences in the overcrowding rates between the two groups were observed in Sweden (24.5 pp), the Czech Republic (21.7 pp), Hungary (20.9 pp) and Slovakia (19.8 pp). On the other hand, the smallest differences were observed in Estonia, Cyprus, Ireland and Croatia (each presented a difference of less than 4 pp).

Apart from the overcrowding rate, other gauges, such as the size of the dwelling, can also provide a representative picture of housing quality, in terms of the availability of sufficient useful space in the dwelling.

In 2012 (no later data available), the average size of the dwelling at EU-28 level was 95.9 m2. The average useful floor area of a dwelling varied in size from 44.6 m2 in Romania, 62.5 m2 in Latvia and 63.2 m2 in Lithuania, to 141.4 m2 in Cyprus (see Table 2).

Overall, the owners with a mortgage or loan lived in dwellings whose size was on average 119.7 m2, while owners with no outstanding mortgage or housing loan had on average less living space at their disposal (96.8 m2). Among homeowners, this pattern was evident in the majority of EU Member States, except for Spain, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Romania. The same exception applied to Iceland.

On the other hand, Europeans living in rented dwellings had, on average, less useful floor area at their disposal compared to homeowners.

In the case of those living in dwellings with a market price rent, an average size of 74.5 m2 for their dwelling was reported, while those living in dwellings with a reduced price or free of charge reported an average size of 78.7 m2.

Dwellings rented at market price varied in size across EU Member States. In Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovenia rented dwellings at market price were relatively small (less than 50 m2), while in Belgium, Spain, Cyprus and Luxembourg (as well as Iceland and Switzerland) the usable floor in dwellings rented at market price exceeded 80 m2, peaking at 91.9 m2 in Cyprus. Tenants living in dwellings with a reduced price or free of charge had relatively more usable floor space at their disposal and exceeded 100 m2 in Denmark, Cyprus, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Sweden.

Housing quality — housing deprivation

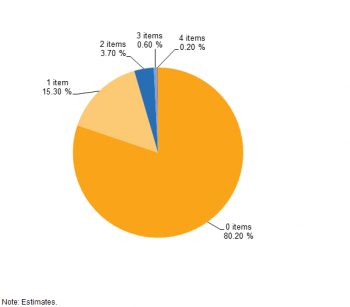

Housing quality can also be assessed by looking at other housing deficiencies, such as lack of certain basic sanitary facilities in the dwelling (a bath or shower or indoor flushing toilet) and problems in the general condition of the dwelling (leaking roof or dwelling being too dark). In 2015 (see Figure 4), 80.2 % of Europeans (EU-28 average) were declared as not deprived for the ‘housing dimension’, 15.3 % were found to suffer from one of the dwelling problems, 3.7 % suffered from two, 0.6 % suffered from three and 0.2 % suffered from all four dwelling problems (i.e. leaking roof/damp walls/floors/foundation or rot in window frames AND accommodation being too dark AND no bath/shower AND no indoor flushing toilet for sole use of the household).

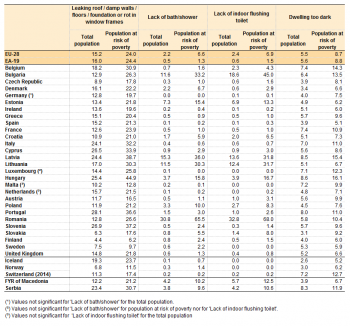

At EU level, the main housing problem was found to be the ‘leaking roof’ (i.e. leaking roof or damp walls, floors or foundation, or rot in window frames of floor’) (15.2 %), followed by ‘darkness of the dwelling’ (5.5 %), while around 2.4 % of the EU population lacked basic sanitary facilities (i.e. lack of bath/shower or indoor flushing toilet) (see Table 3). Exceptions to this EU trend were Bulgaria and Romania, where sanitary problems were found to be more frequent than the other two housing problems mentioned above. In Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands and Sweden, nobody was reported to be lacking an indoor flushing toilet. At the other extreme, 30.8 % of the people in Romania had no bath or shower — followed by Latvia (15.3 %), Bulgaria (11.6 %) and Lithuania (11.5 %), and in the case of ‘lack of indoor flushing toilet’, the percentages in these Member States were also the highest among the EU-28, with 32.8 %, 13.6 %, 18.6 % and 12.4 % respectively.

Overall, people at risk of poverty suffered more than the total population from certain housing problems (or were deprived to a greater extent than the total population for the particular items). This was particularly the case in Romania, where the deficiency of basic sanitary facilities was found to be extremely common; 65.5 % of the at-risk-of poverty populations were found not to have a bath or shower and 68.0 % did not have indoor flushing toilet. In Bulgaria, 45.0 % of the at-risk-of-poverty population was found to be lacking indoor flushing toilet and 33.2 % was found to be lacking a bath or a shower. In Hungary, 44.9 % of the at-risk-of-poverty population suffered from a ‘leaking roof’.

There were also countries where people at risk of poverty suffered less from certain housing problems (although still more than the total population). In Germany, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Spain and Ireland, for instance, there was scarcely any lack of shower or bath for the population at risk of poverty. In Luxembourg, Malta and Sweden, virtually the entire population at risk of poverty had access to an indoor flushing toilet.

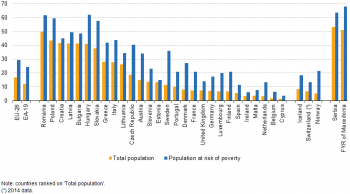

Insufficient spacing and poor amenities are characteristics used to define severe housing deprivation. In 2015, the severe housing deprivation rate in the EU was 4.9 % and it was more than double that figure (12.3 %) for the population that was at risk of poverty (see Figure 5). The highest rates for the total population were exhibited by Romania (19.8 %), Latvia and Hungary (both with 15.5 %). The severe housing deprivation rate was below 1 % of the total population in Belgium, Finland and Cyprus. In Romania and Hungary more than one third of the population that was at risk of poverty faced severe housing deprivation (44.7 % and 35.0 % respectively).

The severe housing deprivation rate of the population at risk of poverty was from 1.6 to 4.9 times greater than for the total population. At EU-28 level, this ratio stood at 2.5. The discrepancy was even larger in Norway, where the rate was found to be 5.3 times greater for the at-risk-of-poverty population.

Housing quality — problems in the residential area

Housing quality depends not only on the quality of the dwelling itself, but also on the wider residential area. In this case the indicators rely on the subjective opinion of the respondents, but have the advantage of drawing a more complete picture of housing.

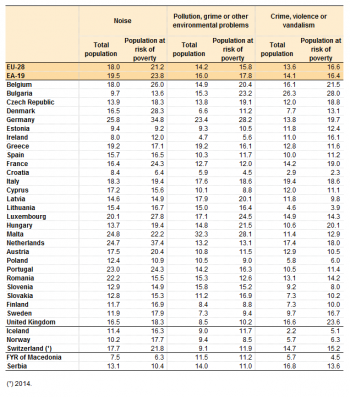

In 2015, 18.0 % of the EU-28 population lived in a dwelling where noise from neighbours or from the street was perceived as a problem (see Table 4). 25.8 % of people in Germany were concerned with noise, followed by Malta (24.8 %), the Netherlands (24.7 %), Portugal (23.0 %) and Romania (22.2 %). At the other extreme, the rates were lowest in Ireland (8.0 %), Croatia (8.4 %), Estonia (9.4 %) and Bulgaria (9.7 %). The same holds true for the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (7.5 %) and Norway (10.2 %).

In 2015, 14.2 % of the EU-28 population perceived the area in which they lived as being affected by pollution, grime or other environmental problems. At the country level, the figures ranged from less than 10 % in Denmark, Ireland, Croatia, Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom to 32.3 % in Malta. Rates were also low in Iceland (9.0 %) and Norway (9.4 %).

Crime and/or vandalism were perceived as a problem by 13.6 % of the EU-28 population in 2015. At the country level, the rates were highest in Bulgaria (26.3 %) and Italy (19.4 %), while only 4.6 % in Lithuania and 2.9 % of the population in Croatia considered this to be a problem. Rates were also low for Norway, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (both with 5.7 %) and Iceland (2.2 %).

Data sources and availability

The data used in this section are primarily derived from micro-data from EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). The reference population is all private households and their current members residing in the territory of the Member State at the time of data collection; persons living in collective households and in institutions are generally excluded from the target population. The EU-28 aggregate is a population-weighted average of individual national figures.

Data used in this article related to the average space in the dwelling come from the EU-SILC 2012 ad-hoc module on housing conditions, which was firstly carried out in 2007.

Context

Questions of social housing, homelessness or integration play an important role within the EU’s social policy agenda. The charter of fundamental rights stipulates in Article IV-34 that ‘in order to combat social exclusion and poverty, the Union recognises and respects the right to social and housing assistance so as to ensure a decent existence for all those who lack sufficient resources, in accordance with Community law and national laws and practices’.

However, the EU does not have any responsibilities in respect of housing; rather, national governments develop their own housing policies. Many countries face similar challenges: for example, how to renew housing stocks, how to plan and combat urban sprawl, how to promote sustainable development, how to help young and disadvantaged groups to get onto the housing market, or how to promote energy efficiency among house owners.

In order to draw a more complete picture of housing conditions, the 2012 module on housing conditions complements existing indicators derived from the core EU-SILC instrument with subjective data about people’s perceptions of their housing conditions. Additionally, the collected statistics permit analyzing the evolution of the results on this topic and in continuation of the former (2007) ad-hoc module.

See also

- Housing statistics

- Housing price statistics - house price index

- Income poverty statistics

- People at risk of poverty or social exclusion

- Statistics on European cities

- Quality of life indicators

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Quality of life - Facts and views

- Living conditions in Europe — 2014 Edition *European social statistics (2013)

- Housing conditions in Europe in 2009 — Statistics in focus 4/2011

- Income and living conditions in Europe — Statistical books

- The social situation in the European Union 2009 — Statistical books

- Combating poverty and social exclusion

Main tables

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (t_ilc_ip)

- Living conditions (t_ilc_lv)

Database

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

- Housing conditions (ilc_lvho)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- Housing deprivation (ilc_mdho)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

- The production of data on homelessness and housing deprivation in the European Union: survey and proposals

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

Other information

- Regulation (EC) No 1177/2003 of 16 June 2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation (EC) No 1553/2005 of 7 September 2005 amending Regulation 1177/2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation (EC) No 1791/2006 of 20 November 2006 adapting certain Regulations and Decisions in the fields of ... statistics, ..., by reason of the accession of Bulgaria and Romania