Archive:Construction statistics - NACE Rev. 2

- Data from October 2015, most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database Planned article update: October 2016

This article presents information relating to the construction sector in the European Union (EU), as covered by NACE Rev. 2 Section F. It belongs to a set of statistical articles on 'Business economy by sector'.

(% share of sectoral total) - Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

(% share of value added and employment in the non-financial business economy total) - Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

(cumulative share of the five principal Member States as a % of the EU-28 total) - Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

(% share of sectoral total) - Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

(% share of sectoral employment) - Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_con_r2)

(% share of sectoral value added) - Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_con_r2)

(thousands) - Source: Eurostat (sbs_r_nuts06_r2)

Main statistical findings

The financial and economic crisis had a major impact on the construction sector in nearly all EU Member States. Output and employment fell sharply in many countries, particularly in Spain and the Baltic Member States. Construction output in the EU-28 peaked in February 2008, after which substantial falls in activity were recorded, reaching a low in February 2010, two years after the initial downturn. Between February 2008 and February 2010 the index of production for construction in the EU-28 fell by 18.6 % overall. From this low point at the beginning of 2010, construction output remained relatively stable through to September 2011. Thereafter, there was a second downturn in activity within the EU-28’s construction sector, with a relative low being reached in March 2013, when output had fallen by a further 9.6 % compared with its September 2011 level. From the spring of 2013 through to August 2014 there was a fluctuating pattern to the development of construction output in the EU-28, although the overall result was an increase of 6.1 % in the level of the index of production. The considerable changes in market conditions for the construction sector since 2008 should be borne in mind when considering the data presented in this article which relates to the situation in 2012.

Structural profile

The EU-28’s construction sector (Section F) was made up of 3.3 million enterprises in 2012, employing 12.7 million persons and generating EUR 492.9 billion of value added. As such, the construction sector accounted for 14.7 % of all the enterprises in the non-financial business economy (Sections B to J and L to N and Division 95), employed 9.5 % of its workforce, and generated 8.0 % of its value added. The construction sector can be characterised as having enterprises that are, on average, smaller than the non-financial business economy average both in terms of their employment levels or their added value.

The share of personnel costs in operating expenditure (personnel costs plus purchases of goods and services) was 23.9 % in the EU-28’s construction sector in 2012, above the non-financial business economy average of 15.8 %, underlining the importance of labour input in the construction activity as a whole. A number of construction activities (at a more detailed level) are also relatively capital-intensive, for example, the construction of roads and railways (Group 42.1) or the development of building projects (Group 41.1).

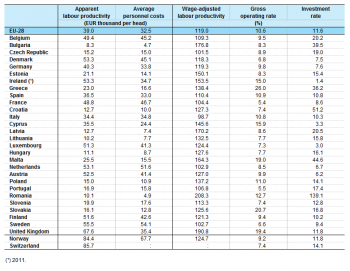

Apparent labour productivity in the EU-28’s construction sector in 2012 was EUR 39.0 thousand per person employed and average personnel costs were EUR 32.5 thousand per employee. While apparent labour productivity was below the average for the non-financial business economy (EUR 46.2 thousand per person employed), average personnel costs per employee were marginally higher than the non-financial business economy average (EUR 32.4 thousand per person employed). The relatively low level of the apparent labour productivity is all the more notable given the small proportion of part-time employment within the construction sector: part-time employment has the effect of making this ratio lower as this productivity measure is calculated on a per head basis. The wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio combines the ratios for apparent labour productivity and average personnel costs and is less affected by the issue of part-time employment and so facilitates analysis between activities. This ratio is also adjusted for the relative importance of unpaid working proprietors and family workers — which is higher in the construction sector (20.3 %) than in the non-financial business economy as a whole (13.7 %). The wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio shows that value added per person employed in the EU-28’s construction sector in 2012 was equivalent to 119.0 % of the average personnel costs per employee, well below the average for the whole of the non-financial business economy (142.7 %); indeed, this was the second lowest value for this indicator across any of the NACE sections that make-up the non-financial business economy, higher only than for the professional, scientific and technical activities (Section M).

Unlike for productivity indicators, the gross operating rate (the relation between the gross operating surplus and turnover) of the construction sector in the EU-28 in 2012 was above the average for the non-financial business economy, reaching 10.6 % compared with 9.4 %. This is partly an effect of the relatively high share of self-employment in construction, as working owners and other unpaid persons contribute to the value added but are recompensed through a share of profits (not in the form of personnel costs), so boosting the gross operating surplus.

Sectoral analysis

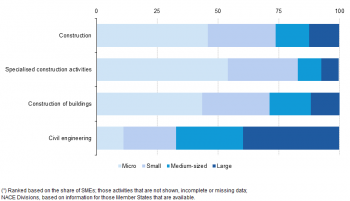

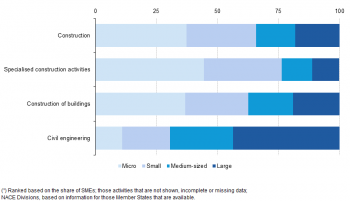

There were 2.4 million enterprises in the EU-28’s specialised construction activities subsector (Division 43) in 2012, more than seven tenths (71.9 %) of all construction enterprises. Around 824 thousand enterprises or 25.1 % of the construction total, were classified to the construction of buildings subsector (Division 41) and the rest (98 thousand or 3.0 %) were in the civil engineering subsector (Division 42).

On average, civil engineering enterprises in the EU-28 in 2012 were considerably larger than other construction enterprises, due in part to the large-scale investment that is often required in plant and machinery for this subsector. The civil engineering share of construction employment was 12.5 % and its value added share reached 14.9 % compared with the above mentioned 3.0 % share in the number of construction enterprises. The construction of buildings subsector also accounted for a larger proportion of construction employment (26.5 %) and value added (28.0 %) than its share of the total number of construction enterprises (25.1 %). Although the specialised construction activities subsector accounted for a smaller share of employment (61.0 %) and value added (57.1 %) than its comparative share based simply on the number of enterprises, it was nevertheless the largest subsector according to both of these measures and contributed more than half of the construction total for both variables.

EU-28 apparent labour productivity in 2012 ranged from EUR 36.0 thousand per person employed in the specialised construction activities subsector to EUR 46.0 thousand per person employed for civil engineering, the latter being at a similar level to the non-financial business economy average (EUR 46.2 thousand per person employed). Average personnel costs ranged from EUR 29.4 thousand per employee for the construction of buildings, which was below the non-financial business economy average (EUR 32.4 thousand per employee), to EUR 35.6 thousand per employee for civil engineering. As already noted, the wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio for the construction sector was the second lowest among any of the NACE sections that compose the non-financial business economy: this was in large part due to the particularly low ratio (109 %) for the specialised construction activities subsector. Indeed, this subsector posted the sixth lowest wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio in 2012 for the EU-28 across all of the NACE divisions covered by the non-financial business economy. The wage-adjusted labour productivity ratios for building (139 %) and for civil engineering (130 %) were also below the EU-28 non-financial business economy average (142.7 %).

Country analysis

In value added terms, the United Kingdom and France had the largest construction sectors in the EU in 2012, the former accounting for a 17.8 % share of the EU-28 total, while the share of France was 17.5 %. As such, the relative contribution of France and the United Kingdom to EU-28 value added in the construction sector was somewhat higher than their contribution to the non-financial business economy as a whole; the same was true for Italy and Spain, while Germany’s contribution to EU-28 value added in the construction sector (16.0 %) was considerably less than its corresponding share of the value added generated in the EU-28’s non-financial business economy (22.4 %). In value added terms, the United Kingdom had the largest subsectors for the construction of buildings (22.8 % of the EU-28 total in 2012) and civil engineering (20.9 %); and France the largest subsector for specialised construction activities (23.0 %).

The construction sector contributed 12.9 % of total added value in the Cypriot non-financial business economy in 2012, making this the most specialised EU Member State in value added terms; the next highest share was 10.9 % in Luxembourg and Finland. The least specialised Member State, in value added terms, was Hungary as the construction sector contributed just 4.7 % of non-financial business economy value added, which was somewhat higher than half the EU-28 average (8.0 %); Germany and Bulgaria were the next least specialised Member States in the construction sector. In employment terms, Cyprus remained near the top of the ranking, as construction occupied 12.7 % of the non-financial business economy workforce; however, Luxembourg reported a higher share (16.9 %).

Productivity in the EU Member States can be compared using the wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio which shows the relative level of value added per person employed compared with average personnel costs per employee, in other words the average value of output compared with the average cost of personnel input. Romania and Bulgaria had, by far, the lowest average personnel costs in the construction sector in 2012 and this was reflected in their relatively high wage-adjusted labour productivity ratios (208.3 % and 176.8 % respectively). The United Kingdom, on the other hand, recorded the highest level of apparent labour productivity within the construction sector combined with average personnel costs per employee just moderately above the EU-28 average resulting in the second highest wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio (190.8 %). The lowest wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio was recorded in Italy (98.7 %). As such, average personnel costs per employee were not covered by the added value generated by each person employed in the Italian construction sector in 2012. The next lowest wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio in this sector was 101.5 % in the Czech Republic.

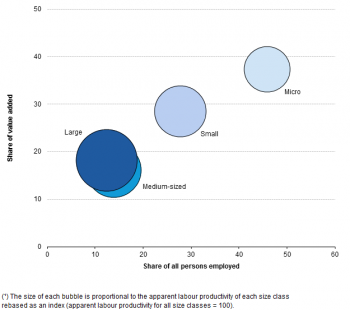

Size class analysis

Most construction enterprises serve a local market and consequently the enterprise size structure of the construction sector is characterised by a large number of quite small enterprises and relatively few large ones. Micro and small enterprises (employing fewer than 50 persons) together employed 73.6 % of the EU-28’s workforce in the construction sector in 2012, a higher share than nearly all of the NACE sections in the non-financial business economy: the average for the non-financial business economy was 49.9 %. Large enterprises (employing more than 250 persons) provided employment for one eighth of the EU-28’s workforce (12.4 %) in construction, compared with a non-financial business economy average of one third (33.0 %). Most EU Member States displayed a similar pattern, as in 2012 the combination of micro and small enterprises employed a majority of the construction sector’s workforce in all Member States. The largest contribution from large enterprises was 22.0 % of the workforce in the United Kingdom.

The particularly high share of the construction workforce in micro and small enterprises was elevated by the specialised construction activities subsector, as here 82.8 % of those employed in the EU-28 workforce were employed by micro or small enterprises in 2012 and just 7.1 % in large enterprises. By contrast, in the civil engineering subsector the combined share of micro and small enterprises was a 32.7 % share of the EU-28 workforce, while the share of large enterprises reached 39.6 %. In terms of value added, large civil engineering enterprises contributed an even greater share of the subsector’s total, reaching 43.6 %, compared with 18.1 % for the whole of construction.

Regional analysis

The French capital city region of the Île de France and the northern Italian region of Lombardia (including the city of Milan) recorded the highest number of persons employed in 2012 in the construction sector, across the NUTS level 2 regions of the EU. In the Île de France, the construction workforce was 346.5 thousand strong, while in Lombardia it numbered 300.5 thousand persons, which represented more than 2 % of the EU-28 total in both cases. The region with the next largest construction workforce was Rhône-Alpes in France with more than 200 thousand persons employed. Overall, the top 20 list was dominated by Italian regions of which there were seven, accompanied by four regions each from Spain and France, two from Poland, as well as one each from Germany, the Netherlands and Portugal. These top 20 regions together accounted for 23.9 % of the EU-28’s construction workforce. Among the seven EU Member States with at least one region in the top 20, the capital city region did not figure for three countries: the Portuguese region of Lisboa had the 38th largest construction workforce among the EU regions while the Dutch capital city region of Noord-Holland had the 50th and the German region of Berlin the 61st largest construction workforce. As well as four capital city regions, the top 20 contained many other regions with major cities such as the regions containing Barcelona, Seville, Valencia, Lyons, Marseille, Milan, Turin, Venice and Rotterdam. The vast majority of the top 20 regions can be described as being located in southern Europe, with the notable exceptions of the Polish, Dutch and German regions, as well as the more northerly French regions.

The relative importance of the construction sector can be analysed by comparing the employment of this sector with the non-financial business economy workforce. Among the 194 NUTS level 2 regions for which data are available in 2012, the median share of the construction sector in the non-financial business economy workforce was 10.4 %. Employment within the construction sector was quite widespread, although at the top end of the ranking there were a number of regions where a particularly high share of non-financial business economy employment was in the construction sector: in 11 of the 194 regions for which data are available, the construction sector accounted for more than 15.0 % of the non-financial business economy workforce. Six of these 11 regions were in France, mainly in the south and centre of the country, notably the region of Centre where the share peaked at 18.3 %. The remaining five regions were shared between Belgium (Province Namur, Province Liège), Italy (Valle d’Aosta/Vallée d’Aoste), Luxembourg, and the Austrian region of Burgenland. There were few regions that were particularly unspecialised in the construction sector in employment terms. The British capital city region recorded the lowest share, with the construction sector employing only 3.7 % of its non-financial business economy workforce.

Data sources and availability

Coverage

This article presents an overview of statistics for the construction sector in the EU, as covered by NACE Rev. 2 Section F. The NACE classification distinguishes between two general types of construction activity — construction of buildings (Division 41) and civil engineering (Division 42) —and a collection of specialised activities (Division 43). These three NACE divisions are:

- construction of buildings (Division 41);

- civil engineering (Division 42);

- specialist activities (Division 43), such as:

- site preparation (including demolition and earth moving),

- installation activities (such as, installation of electrical wiring and fittings, heating systems, plumbing, elevators and insulation),

- completion and finishing activities (such as, plastering, joinery, flooring, glazing or painting),

- other specialist activities, such as, roofing, pile driving, scaffolding.

Some technical activities related to the construction sector, although not formally part of it, such as architectural services, are classified as business services (see article on professional, scientific and technical activity statistics). Some providers of real estate services are closely related to construction and these services are covered in the article on real estate activity statistics.

Data sources

The analysis presented in this article is based on the main dataset for structural business statistics (SBS), size class data and regional data, all of which are published annually.

The main series provides information for each EU Member State as well as a number of non-member countries at a detailed level according to the activity classification NACE. Data are available for a wide range of variables.

In structural business statistics, size classes are generally defined by the number of persons employed. A limited set of the standard structural business statistics variables (for example, the number of enterprises, turnover, persons employed and value added) are analysed by size class, mostly down to the three-digit (group) level of NACE. The main size classes used in this article for presenting the results are:

- small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): with 1 to 249 persons employed, further divided into;

- micro enterprises: with less than 10 persons employed;

- small enterprises: with 10 to 49 persons employed;

- medium-sized enterprises: with 50 to 249 persons employed;

- large enterprises: with 250 or more persons employed.

Regional SBS data are available at NUTS levels 1 and 2 for the EU Member States and Norway, mostly down to the two-digit (division) level of NACE. Regional data for Croatia was not available for 2012. The main variable analysed in this article is the number of persons employed. The type of statistical unit used for regional SBS data is normally the local unit, which is an enterprise or part of an enterprise situated in a geographically identified place. Local units are classified into sectors (by NACE) normally according to their own main activity, but in some EU Member States the activity code is assigned on the basis of the principal activity of the enterprise to which the local unit belongs. The main SBS data series are presented at national level only, and for this national data the statistical unit is the enterprise. It is possible for the principal activity of a local unit to differ from that of the enterprise to which it belongs. Hence, national SBS data from the main series are not necessarily directly comparable with national aggregates compiled from regional SBS.

Context

Construction activity and construction products (structures) have a number of specific characteristics that differentiate them from many areas of the economy. One of the most important of these is that the final product in construction is one of only a few non-transportable goods, as well as being one of the most durable of human artefacts, forming the physical infrastructure where people live and work. Many construction projects are one-off designs and, furthermore, the time scale for many projects from conception to completion is typically longer than in many other sectors, and may run to several years.

Public procurement is especially important for construction as the public sector is a major purchaser of buildings and particularly civil engineering works. Construction is one of the most geographically dispersed activities with marked regional differences in styles of architecture, building materials and techniques. Construction plays a very important economic role in some regions, particularly those associated with tourism, those that are transport and communication hubs, or cultural and sporting centres. Construction is also a highly heterogeneous activity depending on a large number of different specialists. The structure of the construction sector can be viewed as a pyramid, with project coordinating enterprises at the top, subcontracting out work to smaller, specialised enterprises in lower tiers.

In many of the EU Member States, construction activity is seasonal as it is often conducted in the open air or in unfinished structures without heating or air conditioning. Over a longer time period, construction is often sensitive to the overall economic cycle. As a provider of tangible assets it typically leads overall economic movements, although this has not been the case following the recent financial and economic crisis where the downturn in construction activity has continued for much longer than in a range of other activities.

One issue that has gained greater visibility in recent years has been the energy efficiency of structures and the sustainability of construction methods. In 2010, the recast energy performance of buildings Directive was adopted (replacing a 2002 directive on the same subject) in order to strengthen the energy performance requirements of the original directive and to clarify and streamline some of its provisions. Under the new directive, the EU Member States must apply minimum requirements as regards the energy performance of new and existing buildings, ensure the certification of their energy performance, and require the regular inspection of boilers and air conditioning systems in buildings.

In 2011, the construction products Regulation replaced the construction products Directive that was passed in 1989. This regulation lays down harmonised conditions for the marketing of construction products and forms the central part of the EU’s legislation for a single market in the construction sector. In a similar vein, a Commission Recommendation on Eurocodes was adopted in December 2003 to promote the use of harmonised methods for calculating the strength of structural construction products. The full set of Eurocodes were published in 2006 and cover 10 design areas: the basis of structural design, actions on structures, steel, concrete, composite steel and concrete, timber, masonry and aluminium structures, as well as geotechnical design and seismic design.

See also

Structural business statistics introduced

More detailed analysis of construction activities:

Other analyses of the business economy by NACE Rev. 2 sector

Background articles for short-term statistics related to construction:

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- European business - facts and figures (online publication)

- Key figures on European Business – with a special feature section on SMEs – 2011 edition

Main tables

Database

- SBS - industry and construction (sbs_ind_co)

- Annual detailed enterprise statistics - industry and construction (sbs_na_ind)

- Annual detailed enterprise statistics for construction (NACE Rev. 2, F) (sbs_na_con_r2)

- SMEs - Annual enterprise statistics by size class - industry and construction (sbs_sc_ind)

- Construction by employment size class (NACE Rev. 2, F) (sbs_sc_con_r2)

- Annual detailed enterprise statistics - industry and construction (sbs_na_ind)

- SBS - regional data - all activities (sbs_r)

- SBS data by NUTS 2 regions and NACE Rev. 2 (from 2008 onwards) (sbs_r_nuts06_r2)

Dedicated section

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

Other information

- Decision 1578/2007/EC of 11 December 2007 on the Community Statistical Programme 2008 to 2012

- Regulation (EC) No 295/2008 of 11 March 2008 concerning structural business statistics

External links

- Joint research centre, see: