Archive:Being young in Europe today - labour market - access and participation

This article has been archived. For updated articles on youth, please visit the Youth section in Statistics Explained.

Highlights

In 2019, 34 % of young people in the EU-27 aged 20-24 years were exclusively in education, 33 % were exclusively in employment, 19 % combined education and employment and 15 % were neither in employment nor in education or training.

In 2019, 10 % of people aged 15-24 years and 17 % of people aged 25-29 years in the EU-27 were neither in employment nor in education or training.

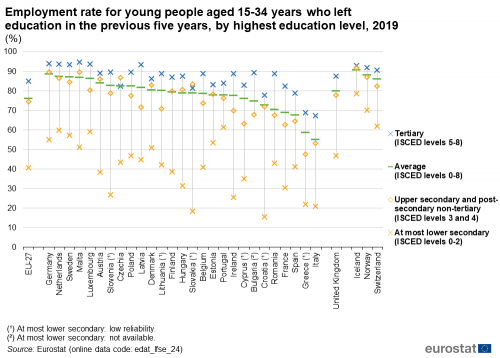

In 2019, the EU-27 employment rate for young people aged 15-34 years who had left education during the previous five years was 76 %, with rates of 85 % for those with a tertiary level of education and 41 % for those with at most a lower secondary level of education.

This is one of a set of statistical articles that forms Eurostat’s flagship publication Being young in Europe today.

Young people represent an important source of skills, creativity and dynamism and a better harnessing of these qualities could help Europe’s economy grow and become more competitive. However, the youth unemployment rate rose steadily during the period 2008-2013, turning it into a major concern for the EU; there followed six consecutive years of consistent falls in youth unemployment rates through until 2019.

This article looks at the labour situation of young people from different perspectives. Firstly, the education and employment patterns characteristic of young people are examined. Next, the focus is put on the transition from education into the labour market by looking at the average age of students when leaving formal education, the average time elapsed between leaving formal education and starting a first job, and employment rates for young people after leaving education. In the final section, the situation of young people in the labour market is described by looking at a number of areas — employment rates, working arrangements (such as part-time and temporary work contracts), as well as unemployment rates.

Full article

The Europe 2020 strategy

The Europe 2020 strategy dedicated two of its flagship initiatives to improving the employment situation of young people: Youth on the move, which promoted mobility as a means of learning and increasing employability (this campaign ended in December 2014), and An agenda for new skills and jobs: a European contribution towards full employment (COM(2010) 682), which aimed to improve employability and employment opportunities for young people.

In order to reduce youth unemployment and to increase youth employment rates in line with the goals identified in the Europe 2020 strategy, a set of measures were adopted at EU level:

- A Youth employment package was adopted in 2012: it included a set of measures to facilitate school-to-work transitions. The Youth guarantee was one of these measures. It helps to ensure that all young people under the age of 25 get good-quality employment offers, continued education, or an apprenticeship/traineeship within four months of leaving school or becoming unemployed.

- The Youth employment initiative (YEI) was initially agreed in 2013 to reinforce and accelerate measures outlined in the ‘Youth employment package’; it was subsequently extended in 2017. It supports particularly young people not in education, employment or training in regions with a youth unemployment rate above 25 %.

- In June 2016, the European Commission adopted a new Skills Agenda for Europe (COM(2016) 381 final), based around 12 priority actions designed to provide the right training, skills and employment support to people in the EU. It forms part of the Recovery plan for Europe which was agreed in July 2020, providing a paradigm shift in skills to take advantage of green and digital transitions, as well as supporting a prompt recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

- In December 2016, the European Commission proposed a Communication in relation to Investing in Europe’s Youth (COM(2016) 940 final), providing a renewed effort to provide young people with better opportunities: to access employment; through education and training; for solidarity, learning mobility and participation.

Education and employment patterns

A gradual change from education to employment

Young people may start work while they are still studying, for example, through evening, weekend or summer jobs. Furthermore, once they reach adulthood, it has become increasingly common for young people who remain in education to also have a job at the same time, perhaps reflecting the cost of tertiary education courses in some EU Member States.

Compulsory schooling ends between the ages of 15 and 19 across the EU Member States. In 2019, just over 9 out of 10 young people in the EU-27 who were aged between 15 and 19 remained within the education system (either exclusively or in combination with employment), while approximately half (52.7 %) of young people aged 20-24 years continued to participate in education.

Employed persons are all persons aged 15 years and over who worked at least one hour for pay or profit during the reference week (of the statistical survey) or were temporarily absent from such work.

Taking both education (formal and non-formal) and employment situations into consideration, young people can be divided into four broad categories:

- exclusively in education;

- both in education and in employment;

- exclusively in employment; and

- neither in employment nor in education or training (abbreviated NEET).

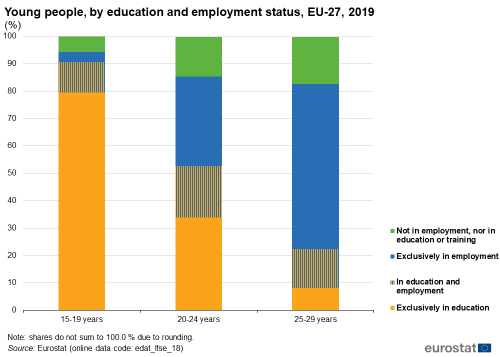

Figure 1 shows that these education and employment patterns differed considerably across the EU-27 according to the age of young people.In 2019, more than three quarters (79.6 %) of young people aged 15-19 years remained exclusively within the education system, while an additional 11.1 % combined their education with employment. Broadly similar shares of young people aged 20-24 years were exclusively in education (34.0 %) or exclusively in employment (32.7 %), while slightly less than one fifth (18.7 %) of this age group combined education and employment; a somewhat lower share (14.5nbsp;%) were neither in employment nor in education or training. By the time young people had reached 25-29 years, it was much more commonplace to find that they had completed their studies and moved into the labour force: in 2019, a majority (60.1 %) of this subpopulation were exclusively in employment. However, more than one sixth (17.2 %) of young people aged 25-29 years were neither in employment nor in education or training, while 14.3 % of this age group combined education and employment opportunities and 8.2 % remained exclusively within the education system.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_18)

Figure 2 presents the education and employment status of young people aged 20-24 years in 2016. Across the EU-27, approximately half (52.8 %) of this subpopulation remained within the education system (exclusively or in combination with employment). Looking at the EU Member States reveals there were 16 where a majority of young people aged 20-24 years continued with education (exclusively or in combination with employment); this share reached a peak of 66.2 % in the Netherlands, while Luxembourg, Denmark, Greece and Sweden each recorded shares within the range of 61-65 %. By contrast, 40-42 % of young people aged 20-24 years from Malta and Romania remained in some form of education, a share that was lower still in Cyprus (38.9 %).

In 2019, Greece (53.8 %) was the only EU Member State to report that more than half of its young people aged 20-24 years remained exclusively within the education system (in other words, they did not combine education with employment). At the other end of the range, this share was between one fifth and one quarter in seven Member States — Germany, Estonia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Austria, Ireland, and Malta; the 20.8 % share in Malta was the lowest. Relatively low shares may reflect, at least to some degree, differences in the length of time taken to complete tertiary education and/or different shares of young people combining their education with employment.

Almost one third (32.7 %) of all young people aged 20-24 years in the EU-27 were exclusively in employment in 2019. This share was more than 40.0 % in Czechia, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Austria and Cyprus and surpassed 50 % in Malta, which recorded the highest share among the EU Member States, at 52.9 %. At the other end of the range, Greece (20.4 %) was the only Member State where less than a quarter of all young people aged 20-24 years were exclusively in employment.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_18)

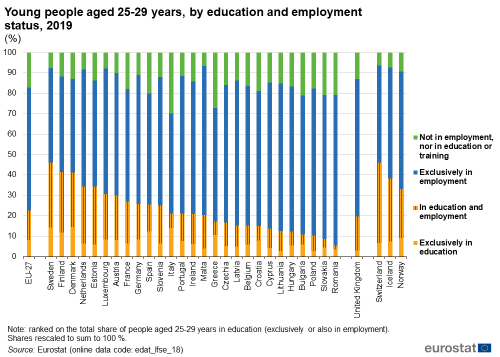

Figure 3 presents a similar set of information but for young people aged 25-29 years; as may be expected it shows that a far larger proportion of this subpopulation in the EU-27 had completed the transition from education into the labour market. As noted above, in 2019, 60.2 % of young Europeans in this age group were exclusively in employment, while an additional 14.3 % combined education and employment. A majority (17.2 %) of the remaining young people aged 25-29 years were neither in employment nor in education or training, leaving 8.2 % exclusively in education.

In 2019, the share of young people aged 25-29 years who were exclusively in employment peaked at 73.9 % in Romania, while shares above 70.0 % were also recorded in Malta, Lithuania, Poland, Cyprus, Hungary, Latvia and Slovakia. Elsewhere, exclusive employment concerned a majority of young people aged 25-29 years in all but four of the EU Member States in 2019: Italy and the three Nordic Member States were the only exceptions. This could be explained, to some degree, by the relatively high (double-digit) shares of young people aged 24-29 years in Italy and the Nordic Member States who remained exclusively in education; Spain and Greece were the only other Member States to report more than 10 % of young people aged 25-29 years exclusively in education. However, in the Nordic Member States the relatively low share of young people aged 25-29 years exclusively in employment could also be attributed to a high share of this subpopulation combining education with employment opportunities (between one quarter and one third). By contrast, in Italy almost three tenths (29.8 %) of all young people aged 25-29 years were neither in employment nor in education or training, which was the highest share among the Member States.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_18)

The organisation of educational systems within individual EU Member States may explain, to some degree, the differences observed when looking at the transition of young people from education to labour markets. As noted above, some of these differences may be linked to the average duration of degree courses: a Bachelor’s degree may exceptionally be two years, but more often three or four years, while some Master’s degrees may last one year and others two; for some subjects, for example medicine or architecture, studies typically last much longer than the usual time for a Bachelor’s degree; some courses include traineeships, placements or studies abroad. These differences in course lengths influence the proportion of students in education, whether exclusively or combined with employment.

Figure 4 shows developments during the period 2009-2019 for the education and employment status of young people aged 20-24 years in the EU-27. Note that the period covered starts in the immediate aftermath of the global financial and economic crisis, which is apparent insofar as education and inactivity substituted employment during the period 2009-2013: a lack of employment opportunities during the crisis may have led some young people to defer their entry into the labour market, seeking instead further or higher education or training to improve their employability, or even to return to education. From 2013 onwards, there were signs of a reversal in these patterns, as the share of young people aged 20-24 years exclusively in employment rose, while the share that was neither in employment nor in education or training fell.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_18)

Young people neither in employment nor in education or training

Young people neither in employment nor in education were more numerous in the 25-29 years age group (than in younger age groups) and were more likely to be women than men

Education or training, whether formal or non-formal, should potentially improve skills and employability. People who are neither in employment nor in education and training are often disconnected from the labour market and have a higher risk of not finding a job, which may lead to a higher risk of poverty and/or social exclusion.

The share of young people neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET) is defined as the percentage of the young population that is simultaneously not employed and not involved in education or training.

Compulsory schooling ends at the age of 15 in some of the EU Member States. Nevertheless, it is common for young people in the EU-27 to remain longer within the education system as they try to acquire more qualifications. Among other benefits, this may help them to find a more interesting or better paid job when they eventually make the transition from education into the labour market. As already noted, in the age groups 15-19 and 20-24 years, it was more common to find a higher share of young people in the EU-27 remaining within the education system than being in employment or economically inactive. This section looks in more detail at the share of young people neither in employment nor in education and training.

© Fotolia

In 2019, 10.1 % of people aged 15-24 years and 17.2 % of people aged 25-29 years in the EU-27 were neither in employment nor in education or training. The lowest proportions of people aged 15-24 years neither in employment nor in education or training were recorded in the Netherlands (4.3 %), Sweden (5.5 %), Luxembourg (5.6 %), Czechia and Germany (both 5.7 %). At the other end of the range, the highest shares were recorded in Italy (18.1 %), Romania (14.7 %), Bulgaria and Cyprus (both 13.7 %).

Comparing 2009 with 2019, there was a reduction in the proportion of young people aged 15-24 years in the EU-27 who were neither in employment nor in education and training; this share fell by 2.2 percentage points during the period under consideration (see Figure 5). The share of young people neither in employment nor in education or training fell between 2009 and 2019 in the majority of EU Member States. The largest reductions were recorded in Latvia (down 9.6 points), Ireland (down 8.2 points; note that there is a break in series) and Estonia (down 7.6 points). As a result of these considerable falls, all three of these Member States posted a NEET rate in 2019 that was equal to or below the rate for the EU-27. By contrast, there were five Member States where the share of young people aged 15-24 years who were neither in employment nor in education and training increased between 2009 and 2019. These increases were of a relatively modest magnitude, with a 3.8 point increase in Cyprus being the highest recorded.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_150)

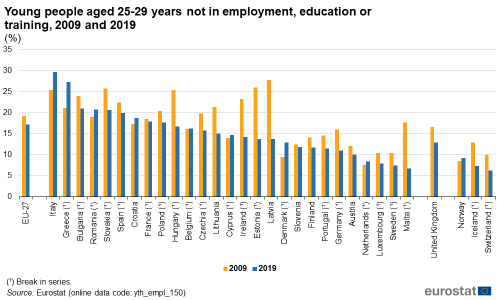

Similar information for young people aged 25-29 years reveals that in 2019 almost three tenths (29.7 %) of this subpopulation in Italy was neither in employment nor in education or training; a similar share was recorded in Greece (27.3 %). At the other end of the range, less than 1 in 10 young people aged 25-29 years in the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Sweden and Malta were neither in employment nor in education or training.

The share of young people aged 25-29 years in the EU-27 neither in employment nor in education and training fell by 2.1 percentage points between 2009 and 2019. This change is composed of some much larger fluctuations among the individual EU Member States, with considerable increases in the NEET rate for young people aged 25-29 years in Greece (6.1 points), Italy (4.2 points) and Denmark (3.4 points); note that there are breaks in series for Greece and Denmark. There were 19 EU Member States where the share of young people aged 25-29 years neither in employment nor in education or training fell between 2009 and 2019. The largest falls — in excess of 10.0 points — were recorded in Latvia, Estonia and Malta, while Ireland, Hungary, Lithuania, Germany and Slovakia all recorded decreases within the range of 5.1-9.0 points (note that there is a break in series for all of these Member States except for Lithuania).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_150)

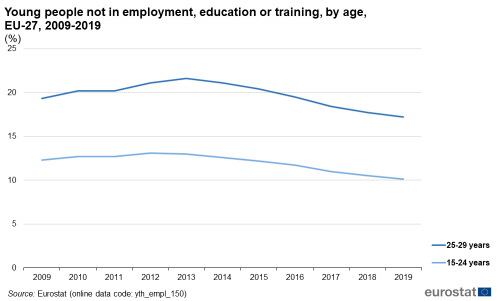

Figure 7 provides an overview of the development for the share of young people in the EU-27 neither in employment nor in education or training during the period 2009-2019. In the years leading up to the global financial and economic crisis, this share was decreasing at a modest pace for both age groups that are presented. Following the onset of the crisis the share of young people neither in employment nor in education or training started to increase, reaching a peak of 13.1 % for young people aged 15-24 years in 2012 and a peak of 21.6 % for young people aged 25-29 years a year later (when the largest gap between these two shares was recorded, at 8.6 percentage points). Both shares subsequently declined and by 2019 the share of young people aged 15-24 years neither in employment nor in education or training was 10.1 %, some 7.1 points lower than the share for young people aged 25-29 years (17.2 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_150)

Figure 8 presents the share of young people aged 25-29 years neither in employment nor in education or training, by sex. In 2019, there was a 9.3 percentage point gap between the sexes across the whole of the EU-27, with a lower share for young men. This pattern was repeated in all but one of the EU Member States with the gender gap rising to 22.2 points in Czechia and 20.5 points in neighbouring Slovakia; these differences between the sexes are often attributed to a higher share of women devoting time to parenting or wider care responsibilities within families. At the other end of the range, there were seven Member States where the gap between the sexes (with a higher share for women) for the share of young people aged 25-29 years neither in employment nor in education or training was less than 5.0 points; the smallest gaps were recorded the Netherlands (1.9 points), Sweden (1.7 points) and Denmark (1.2 points). Luxembourg was the only Member State to report a higher proportion of young men aged 25-29 years neither in employment nor in education or training (9.1 % compared with 6.5 % for young women).

(% share of young men / young women)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_150)

Employment rates after leaving formal education

One important step during the journey into adulthood is the transition out of education into working life. As noted above, the organisation of education systems may play a role in determining whether or not this transition is abrupt with young people finishing their studies and beginning work or spread over a longer period of time with young people experiencing work placements, traineeships or internships while they continue to study, or after a period of inactivity. One way of interpreting the success (or otherwise) of these different types of transition is to look at employment rates among young people who recently left education. The information presented below focuses on people who left education during the five years prior to the survey from which the data are derived. In 2019, the EU-27 employment rate for young people aged 15-34 years who had left education during the previous five years was 75.9 %. The employment rate was considerably higher (84.9 %) among young people with a tertiary level of educational attainment, while it was much lower (40.5 %) for young people who had at most a lower secondary level of educational attainment (see Figure 9).

The employment rate is the percentage of employed persons in relation to the total population. For the overall employment rate, the comparison is made with the population of working-age (usually 20-64 years); but employment rates can also be calculated for other age groups, by sex, or for specific geographical areas.

In almost all of the EU Member States, a similar pattern to that in the EU-27 as a whole was observed when looking more closely at the data by level of education: higher levels of educational attainment were generally beneficial to improving the employment opportunities of young people. It should be noted these figures do not provide any information as to the type of employment being carried out and it may be the case that some young people with a tertiary level of education were over-qualified for the post they occupied. Czechia and Slovakia were the only exceptions where the highest employment rates for young people who left education in the previous five years were recorded for people with an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary level of education (rather than a tertiary level of education).

In 2019, employment rates for young people aged 15-34 years who left education in the previous five years and were in possession of a tertiary level of educational attainment were 90.0 % or more in Malta, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Latvia and Sweden. By contrast, employment rates for recent young graduates with a tertiary level of education were just under 70.0 % in Greece and Italy.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_24)

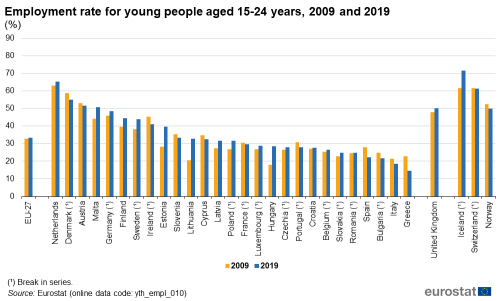

Youth employment rates by age

In 2019, there was a wide disparity between the EU-27 employment rates for young people aged 15-24 years (33.4 %) and young people aged 25-29 years (74.6 %). The highest employment rates for young people aged 15-24 years were recorded in the Netherlands (65.3 %), followed by Denmark (55.0 %), Austria (51.6 %) and Malta (50.9 %); all of the remaining Member States recorded rates below 50.0 %, with Italy and Greece posting rates below 20.0 % (see Figure 10).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_010)

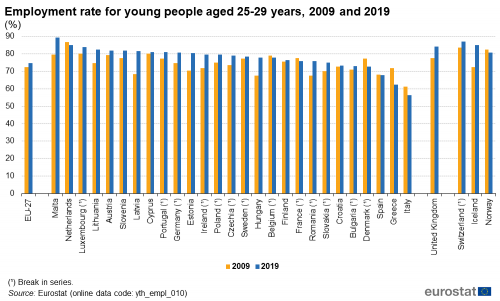

In 2019, the share of young people aged 25-29 years in employment was above four out of every five in Malta (89.2 %), the Netherlands (85.1 %), Luxembourg (83.9 %), Lithuania (82.3 %), as well as in Austria, Slovenia, Latvia, Cyprus, Portugal, Germany and Estonia (all of which recorded employment rates within the range of 80.3-81.8 %). By contrast, the lowest rates were again recorded in Greece (62.2 %) and Italy (56.3 %) — see Figure 11.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_010)

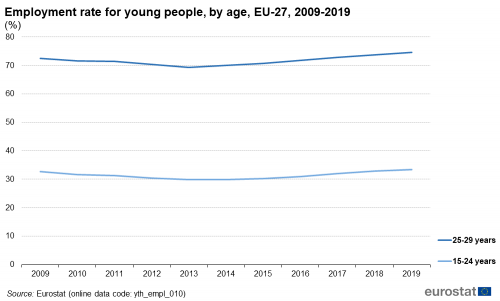

Figure 12 illustrates the development of employment rates for young people in the EU-27 during the most recent decade for which data are available. Although there was a considerable difference in the level of employment rates for young people (rates for young people aged 25-29 years were some 39.5-41.2 percentage points higher than for young people aged 15-24 years), the overall development of both rates was broadly similar. Having peaked in 2008 prior to the global financial and economic crisis, EU-27 employment rates for young people consistently fell through to 2013, after which there was a modest recovery in 2014 and 2015, quickening thereafter; note that the latest employment rates (data for 2019) remained lower than the levels recorded prior to the crisis in 2008.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_010)

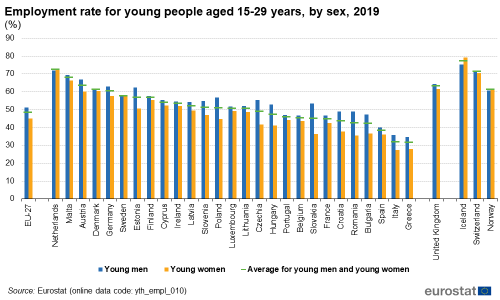

Employment rates were generally lower among young women than they were among young men (see Figure 13). In 2019, the employment rate of young people aged 15-29 years in the EU-27 stood at 51.3 % for men and at 44.9 % for women. With a single exception — the Netherlands — this pattern was repeated in each of the EU Member States, albeit to different degrees. Employment rates for young men were considerably higher than those for young women in Slovakia (17.0 percentage points difference), Czechia (13.7 points difference) and Romania (13.3 points difference), while Poland, Estonia, Hungary, Croatia and Bulgaria also recorded double-digit differences.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_010)

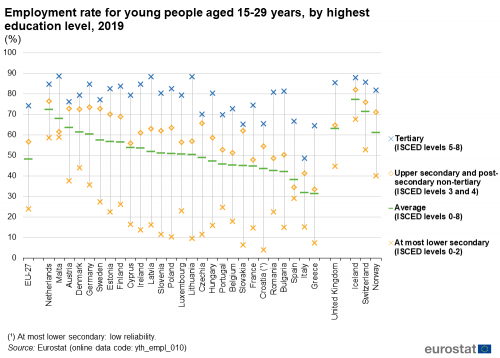

Employment rates among young people varied considerably according to their level of educational attainment (see Figure 14): the EU-27 employment rate of those aged 15-29 years who had completed a tertiary education was 74.3 % in 2019, more than three times as high as the employment rate for young people who had attained no more than primary or lower secondary qualifications (23.9 %). The EU-27 employment rate for young persons with at most upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary qualifications stood at 56.7 %.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_010)

Temporary and part-time work contracts

Temporary work contracts are quite common among young people entering the labour market. These types of contract, which often include seasonal employment, allow employers to adapt to changes in their need for labour input. There is some evidence to suggest that young people who are out of work are more likely to accept these types of contract. Furthermore, employers may use temporary work contracts to assess the capabilities of new recruits before offering them a permanent position.

Temporary and part-time work contracts are two types of agreement that young people are often offered when entering the labour market.

Temporary employment includes work under a fixed-term contract, rather than a permanent work contract where there is no end-date. A job may be considered temporary employment (and its holder a temporary employee) if both employer and employee agree that its end is decided by objective rules (usually written down in a work contract of a limited duration). These rules can be a specific date, the end of a task, or the return of another employee who has been temporarily replaced.

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), part-time employment is defined as regular employment in which working time is substantially less than normal.

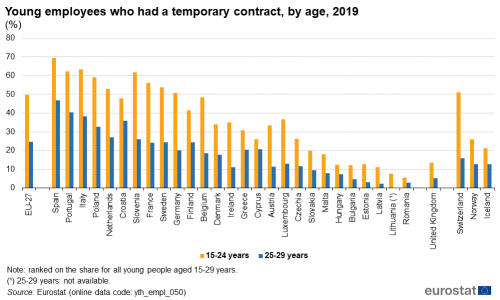

As shown in Figure 15, a relatively high proportion of young people worked with a temporary work contract: in 2019, almost half (49.8 %) of young employees aged 15-24 years in the EU-27 had such a contract, which was approximately twice as high as the corresponding share (24.6 %) among young people aged 25-29 years. This pattern of a greater share of temporary employees for the younger age group was repeated in each of the EU Member States for which data are available.

There were however substantial differences between the EU Member States: the rates of young employees (both age groups) working with temporary work contracts in 2019 were highest in Spain, Portugal, Italy, Poland, the Netherlands, Croatia and Slovenia. Spain had the highest rate for both age groups, as 69.5 % of young employees aged 15-24 years had a temporary contract, while the share among young employees aged 25-29 years was just below half (46.7 %). At the other end of the spectrum, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania and the Baltic Member States were among the Member States with the lowest temporary employment rates in both age groups (note that there is no information available for Lithuania for young employees aged 25-29 years). In Romania, just 5.6 % of employees aged 15-24 years and 2.8 % of employees aged 25-29 years had a temporary contract. Country-specific regulations on temporary work contracts (for example, their maximum duration or renewal possibilities) and differences in national education systems relating to traineeships may explain, at least to some degree, some of these differences.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_050)

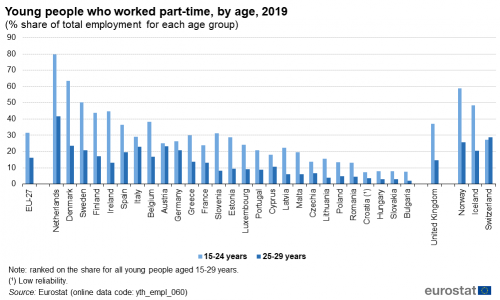

For many young people, part-time work may provide a good way of combining education and employment; however, part-time work may also be used by young people who wish to find a work-life balance (especially for those who are starting a family). As seen for temporary work, part-time work was more widespread among younger age groups. The percentage of young people aged 15-24 years working on a part-time basis in the EU-27 increased almost every year over the latest 10-year period for which data are available (see Figure 16). The share of young people aged 15-24 years working part-time rose at a relatively fast pace during the global financial and economic crisis and then continued to increase, but at a slower rate. In 2019, the proportion of young employed persons aged 15-24 years working on a part-time basis in the EU-27 stood at just less than one third (31.6 %). For young employed persons aged 25-29 years, a similar development was observed between 2009 and 2012, with the relatively fast increase in the share of part-time employment continuing for three more years, to reach a peak of 17.1 % in 2015. Since then, the share has fallen each year, reaching 16.1 % in 2019.

(% share of total employment for each age group)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_060)

In 2019, the highest part-time employment rates for the 15-24 years age group were recorded in the Netherlands (79.7 %) and Denmark (63.6 %), while Croatia, Bulgaria, Hungary and Slovakia were the only EU Member States to record shares that were below 10.0 % (see Figure 17). A similar situation was apparent for young people aged 25-29 years as the highest part-time employment rates were again recorded for the Netherlands (41.6 %) and Denmark (23.5 %), although quite high rates were also registered in Austria (23.2 %), Italy (22.8 %), Germany (20.9 %) and Sweden (20.8 %). At the other end of the range, there were 14 Member States where fewer than 10.0 % of all young persons aged 25-29 years worked on a part-time basis; this share was less than 5.0 % in Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia and Bulgaria (where the lowest share was recorded, at 2.0 %).

(% share of total employment for each age group)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_060)

Part-time employment is not always a matter of personal choice — some young people work part-time because they cannot find a full-time job. Involuntary part-time employment refers to part-time workers who declare that they are working part-time because they could not find a full-time job.

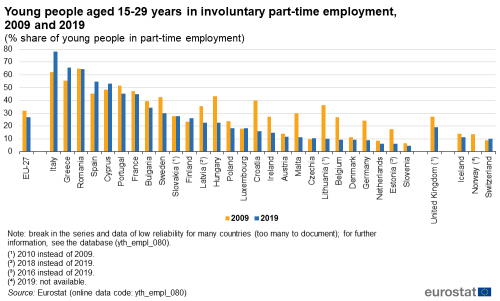

From 2009 to 2019, the share of young people aged 15-29 years in part-time employment in the EU-27 who were in involuntary part-time employment decreased from 31.9 % to 27.0 % (see Figure 18). The share of involuntary part-time employment fell by a considerable margin — more than 20.0 percentage points — in Lithuania (2010-2019), Croatia and Hungary, while there were double-digit reductions in seven more of the Member States. By contrast, the largest increases in involuntary part-time employment were recorded in some of the EU Member States where the impact of the global financial and economic crisis and subsequent sovereign debt crisis was particularly strong, for example, in Italy (up 15.9 points), Greece (10.1 points), Spain (9.2 points) and Cyprus (4.5 points).

(% share of young people in part-time employment)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_080)

In 2019, part-time employment rates for young people aged 15-29 years were above 50.0 % in five of the EU Member States and were particularly high in the southern Member States of Italy, Greece, Spain and Cyprus, as well as in Romania.

The prevalence of part-time work contracts in 2019 was identical in the EU-27 among young men and young women (see Figure 19): the part-time employment rate for young men and young women aged 15-29 years was 27.0 %. There were however some large differences between the sexes when looking at the data for individual EU Member States. For example, the share of employed young men working on a part-time basis was 26.8 percentage points higher than the share for young women in Romania. By contrast, part-time employment rates for young women were 12.3 and 11.0 points higher than for young men in Portugal and Greece.

(% share of total employment for young men/young women/young people)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_060)

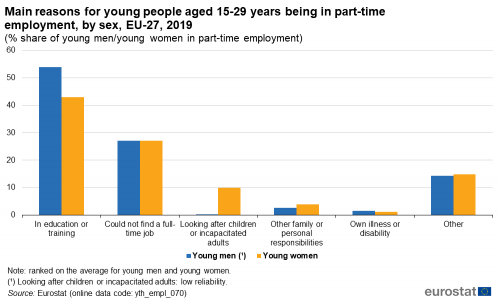

Some of the differences between young men and young women with regard to their part-time employment rates may be related to a range of different factors that are illustrated in Figure 20. It shows that in 2019, the primary reason for young people aged 15-29 years to be working on a part-time basis in the EU-27 was to be able to combine education and training with employment, while the second most important reason was not being able to find a full-time post. Together these two reasons were given by approximately four out of every five (80.9 %) young men in part-time employment, and for seven tenths (70.0 %) of young women in part-time employment. A much higher share (10.0 %) of young women employed on a part-time basis did so because they were looking after children or incapacitated adults (for example family members); the equivalent share for young men was 0.4 %. In a similar vein, the share of young women working on a part-time basis due to other family or personal responsibilities was also higher (3.9 % compared with 2.7 % for young men).

(% share of young men/young women in part-time employment)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_070)

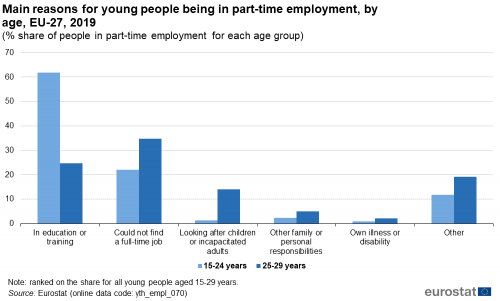

Looking at the main reasons for part-time employment by age group, participation in education or training (61.7 %) and the inability to find a full-time job (22.0 %) were the two main reasons why young people aged 15-24 years in the EU-27 worked on a part-time basis in 2019 (see Figure 21). There was a somewhat different pattern for young people aged 25-29 years, as the relative importance of the two principal reasons was reversed: the inability to find a full-time job was the main reason given by 34.7 % of people working on a part-time basis, whilst being in education and training accounted for approximately one quarter (24.7 %) of the total, ahead of looking after children or incapacitated adults (14.1 %).

(% share of young people in part-time employment for each age group)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_070)

Youth unemployment

Unemployment among young people

Young people, especially those with lower qualifications, still face difficulties in finding a job

The unemployment rate of young people increased in the aftermath of the global financial and economic crisis, with unemployment rates for young people rising at a faster pace than for the population in general. The main indicator for youth unemployment is called the ‘youth unemployment rate’ and refers to the age group 15-24 years.

The youth unemployment rate is the number of unemployed young people in the age group 15-24 years expressed as a share of the total labour force (economically active population) within the same age group.

The active population includes employed and unemployed people, but not people who are economically inactive. Information for young people show that the inactive tend to be school children, students or stay-at-home parents; inactive people do not work at all and are not available or looking for work.

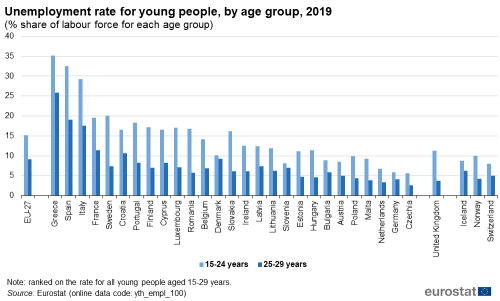

In 2019, 15.1 % of the EU-27’s labour force among young people aged 15-24 years and 9.1 % of its labour force for the 25-29 years age group were unemployed (see Figure 22). Unemployment rates were higher for the younger age group in each of the EU Member States.

The unemployment situation of young people aged 15-24 years varied considerably between the Member States. In 2019, the highest unemployment rates were recorded in Greece (where more than one third of the labour force aged 15-24 years was unemployed; 35.2 %), Spain and Italy. By contrast, at the other end of the range the lowest unemployment rates for the 15-24 years age group were recorded in Czechia (5.6 %) and Germany (5.8 %).

Looking at the difference in unemployment rates between young people aged 15-24 years and young people aged 25-29 years reveals that the largest gaps were generally recorded in the EU Member States characterised by some of the highest overall unemployment rates. In Spain, the youth unemployment rate (for young people aged 15-24 years) in 2019 was 13.5 percentage points higher than the unemployment rate for young people aged 25-29 years, while in Sweden and Italy the difference was 12.7 and 11.6 points; there were four additional Member States which recorded double-digit differences — Romania, Finland, Portugal and Slovakia. By contrast, there was little difference between the unemployment rates for these two age groups in Denmark (0.8 points), Slovenia (1.1 points) or Germany (1.7 points).

(% share of labour force for each age group)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_100)

It is important to note that many young people study full time and so are not available for work and are therefore considered as being outside the labour force, in other words they are economically inactive. For this reason, when presenting the labour situation of young people, the main indicator for unemployment, the youth unemployment rate, is often complemented by the youth unemployment ratio, which compares the number of young unemployed persons with the total population (and not just the labour force) of the same age.

The youth unemployment ratio is the number of young unemployed people in the age group 15-24 years compared with the total population (employed, unemployed and economically inactive) of that age group, expressed as a percentage.

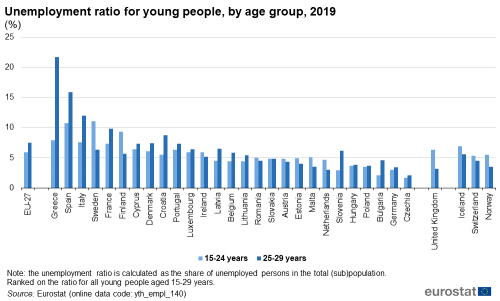

The youth unemployment ratio provides an alternative measure to assess the labour market situation of young people. In 2019, the unemployment ratio for young people aged 15-24 years in the EU-27 stood at 5.9 %, while the corresponding ratio for the 25-29 years age group was 7.5 % (see Figure 23).

A comparison between the results shown in Figures 22 and 23 reveals that there was a stark contrast between the results for the unemployment rate and the unemployment ratio among young people aged 15-24 years. This may be largely attributed to the high numbers of young people aged 15-24 years who remained within full-time education and were therefore unavailable for work (and not included in the denominator used to calculate the unemployment rate).

In 2019, the highest unemployment ratios for young people aged 15-24 years were recorded in Sweden (11.1 %) and Spain (10.7 %), the only EU Member States to report that at least 1 in 10 young persons of this age were unemployed. Unemployment affected less than 1 in 20 young people aged 15-24 years in 13 of the Member States, with Slovenia (2.9 %), Bulgaria (2.1 %) and Czechia (1.7 %) recording the lowest ratios.

In a majority of the EU Member States, the unemployment ratio for young people aged 15-24 years was lower than the ratio for young people aged 25-29 years. In 2019, this difference was greatest, by some margin, in Greece (13.8 percentage points), with unemployment affecting more than one fifth (21.7 %) of all young people aged 25-29 years. The next largest difference (5.2 points) was recorded in Spain, where almost one sixth of all young people aged 25-29 years were unemployed, followed by Italy (4.4 points). These three Member States — Greece, Spain and Italy — were the only Member States where the share of young people aged 25-29 years who were unemployed in 2019 was in double-digits.

There were eight EU Member States where the unemployment ratio for young people aged 15-24 years in 2019 was higher than the ratio for young people aged 25-29 years, although the difference between these two ratios was generally quite small. In Sweden, more than one tenth (11.1 %) of all young people aged 15-24 years were unemployed in 2019, which was 4.8 percentage points higher than the unemployment ratio for young people aged 25-29 years (6.3 %). A similar pattern was observed in Finland, where the unemployment ratio for young people aged 15-24 years was 3.6 points higher than for young people aged 25-29 years. The Netherlands, Malta, Estonia, Ireland, Austria and Romania also had unemployment ratios that were higher for young people aged 15-24 years than for young people aged 25-29 years.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_140)

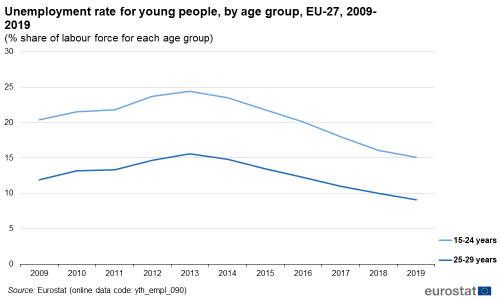

The development of EU-27 unemployment rates for young people during the most recent 10-year period for which data are available (see Figure 24) clearly shows the impact of the global financial and economic crisis. There was a rapid increase in EU-27 unemployment rates for young people in the aftermath of the crisis, as successive increases were recorded between 2009 and 2013. Unemployment rates peaked in 2013 at 24.4 % for young people aged 15-24 years and at 15.6 % for young people aged 25-29 years. Thereafter, there were six consecutive years of falling rates, as the share of unemployed persons in the labour force among young people aged 15-24 years fell to 15.1 % and that for young people aged 25-29 years to 9.1 %; note that these latest rates were slightly lower than those recorded at the onset of the financial and economic crisis in 2008.

(% share of labour force for each age group)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_090)

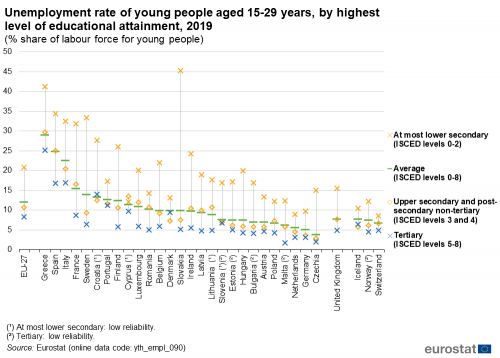

Educational attainment is one of the most important factors that may be used to assess unemployment. Across the EU-27, the unemployment rate for young people aged 15-29 years with a tertiary level of education was 8.2 % in 2019, while it stood at 10.6 % among young people with an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary level of education and peaked at 20.8 % among young people with at most a lower secondary level of education.

This pattern was repeated in the vast majority of the EU Member States in 2019, as Denmark and Croatia were the only Member States where the lowest unemployment rate was not recorded for young people with a tertiary level of education. Cyprus was the only Member State where the highest unemployment rate was not recorded for young people with at most a lower secondary level of education (see Figure 25).

In 2019, unemployment rates for young people aged 15-29 years with a tertiary level of education peaked at 25.1 % in Greece, while there were also double-digit rates recorded in three other southern EU Member States: Italy (16.8 %), Spain (16.7 %) and Portugal (11.2 %), as well as Croatia (14.0 %).

Among young people with at most a lower secondary level of education, unemployment rates ranged from more than 40.0 % in Slovakia and Greece down to less than 10.0 % in Germany and the Netherlands. In Slovakia, the unemployment rate for young people with at most a lower secondary level of education was almost nine times as high as the rate for young people with a tertiary level of education. There was also a relatively large difference in unemployment rates between these two subpopulations in Czechia and Malta, as unemployment rates for young people with at most a lower secondary level of education were between seven and eight times as high as those for young people with a tertiary level of education.

(% share of labour force for young people)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_090)

Long-term unemployment among young people

Long-term unemployment is a major concern for policymakers across the EU. Apart from its financial and social impact on personal lives, long-term unemployment may also have a negative effect on social cohesion and, ultimately, can also hinder economic growth.

The long-term unemployment rate is defined as the proportion of the labour force who have been unemployed for at least 12 months.

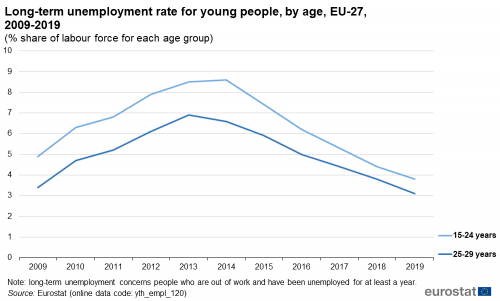

EU-27 long-term unemployment rates for young people fell to relative lows in 2008 at the onset of the global financial and economic crisis, after which they rose at a fairly rapid pace until 2013or 2014 before they started to fall; these developments for long-term unemployment rates closely resembled the recent developments for overall unemployment rates among young people. Having peaked in 2013 at 6.9 % for young people aged 25-29 years and in 2014 at 8.6 % for young people aged 15-24 years, long-term unemployment rates for young people in the EU-27 fell to 3.1 % and 3.8 % respectively (see Figure 26). As such, the latest rate for young people aged 25-29 years remained 0.3 percentage points higher than it had been in 2008, prior to labour markets feeling the impact of the crisis, while the rate for young people aged 15-24 years had returned to the same level as in 2008.

(% share of labour force for each age group)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_120)

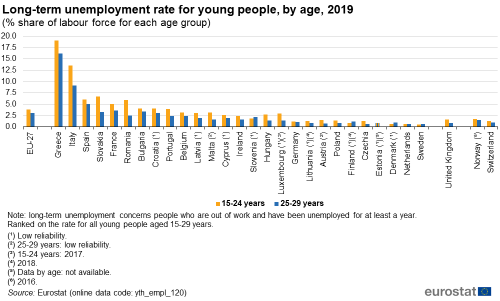

Long-term unemployment rates varied considerably across the EU Member States in 2019 (see Figure 27). Greece and Italy stood out with by far the highest long-term unemployment rates for young people aged 15-24 years, as 19.0 % and 13.5 % of the young Greek and young Italian labour forces had been unemployed for more than 12 months. These two Member States also recorded the highest long-term unemployment rates for young people aged 25-29 years, at 16.2 % in Greece and 9.1 % in Italy. Combining both age groups, long-term unemployment affected less than 1 in 20 persons aged 15-29 years in the labour force in the vast majority (24) of the Member States in 2019: Greece (17.1 %), Italy (10.9 %) and Spain (5.4 %) were the only exceptions. By contrast, long-term unemployment rates for young people aged 15-29 years were less than 1.0 % in Czechia, Estonia, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden.

(% share of labour force for each age group)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_120)

Source data for tables and graphs

![]() Labour market — access and participation: tables and figures

Labour market — access and participation: tables and figures

Data sources

The main source of the data presented in this article is the EU labour force survey (EU-LFS), a large sample survey among private households which provides detailed annual and quarterly data on employment, unemployment and inactivity. The data can be studied across a range of dimensions including age, sex, educational attainment, and distinctions between permanent/temporary and full-time/part-time employment. The concepts and definitions used in the EU-LFS follow the guidelines of the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Context

In 2009, the European Council adopted Resolution 2009/C 311/01 on a renewed framework for European cooperation in the youth field (2010-2018), which set the stage for the EU’s youth strategy. It had two overall objectives:

- to provide more and equal opportunities for young people in education and in the labour market; and

- to promote active citizenship and social inclusion for all young people.

To achieve these objectives, the EU followed a dual approach of:

- specific youth initiatives, targeted at young people to encourage non-formal learning, participation, voluntary activities, youth work, mobility and information;

- ’mainstreaming’ cross-sector initiatives designed to ensure youth issues were taken into account when formulating, implementing and evaluating policies and actions in other fields with a significant impact on young people, such as education, employment or health and well-being.

The EU’s youth strategy was renewed in November 2018 when the European Council adopted Resolution 2018/C 456/01 on a framework for European cooperation in the youth field: the European Union youth strategy 2019-2027. This revised strategy is designed to bring the EU closer to young people and to help address issues of concern to them by focusing on three main areas of action:

- engage — to encourage young people to participate in civic and democratic life;

- connect — to connect young people across the EU and beyond by promoting volunteering, opportunities to learn abroad, solidarity and intercultural understanding;

- empower — to support youth empowerment through boosting innovation in, as well as the quality and recognition of youth work.

The strategy was developed around a dialogue process that involved young people from all over the EU. It collected together the voices of young people and developed these into a list of 11 youth goals that reflect the views of youth in the EU and some of the most pressing challenges that young people face in their daily lives.

Youth on the Move — An initiative to unleash the potential of young people to achieve smart, sustainable and inclusive growth in the European Union presented a framework of policy priorities for action at national and EU level to reduce youth unemployment by facilitating the transition from education into work. It was launched in 2010 and focused on the role of public employment services and promoting the youth guarantee scheme to try to ensure that all young people were in a job, in education or in training.

The Youth Guarantee is a commitment by EU Member States to ensure that all young people under the age of 25 years receive a good-quality offer of employment, continued education, an apprenticeship or a traineeship within a period of four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education. It is based on a Council Recommendation (2013/C 120/01) that was adopted in April 2013.

In its 2016 Communication, Investing in Europe’s Youth (COM(2016) 940 final) the European Commission proposed a renewed effort to support young people through three strands of action:

- better opportunities to access employment;

- better opportunities through education and training;

- better opportunities for solidarity, learning mobility and participation.

The Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) is one of the main EU financial resources to support the implementation of the Youth Guarantee scheme. It was launched to provide support to young people living in regions where youth unemployment was higher than 25 %. The YEI exclusively supports young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEETs), including the long-term unemployed or those not registered as job-seekers. Typically, the YEI funds the provision of apprenticeships, traineeships, job placements and further education leading to a qualification.

Direct access to

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

- Education and training outcomes (educ_outc)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Employment and activity - LFS adjusted series (lfsi_emp)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- Labour market transitions - LFS longitudinal data (lfsi_long)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- Employment and unemployment (Labour force survey) (employ) (ESMS metadata file — employ_esms)

- Labour market transitions — experimental statistics

- LFS main indicators (lfsi) (ESMS metadata file — lfsi_esms)

- LFS series — detailed annual survey results (lfsa) (ESMS metadata file — lfsa_esms)

- Population by educational attainment level (ESMS metadata file — edat1_esms)

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social affairs & Inclusion

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social affairs & Inclusion — Youth employment

- European Commission, Education and Training Monitor

- European Commission, Strategic framework — Education and Training 2020

- International Labour Organisation (ILO)