Agriculture statistics at regional level

Data extracted in March 2023.

Planned article update: September 2024.

Highlights

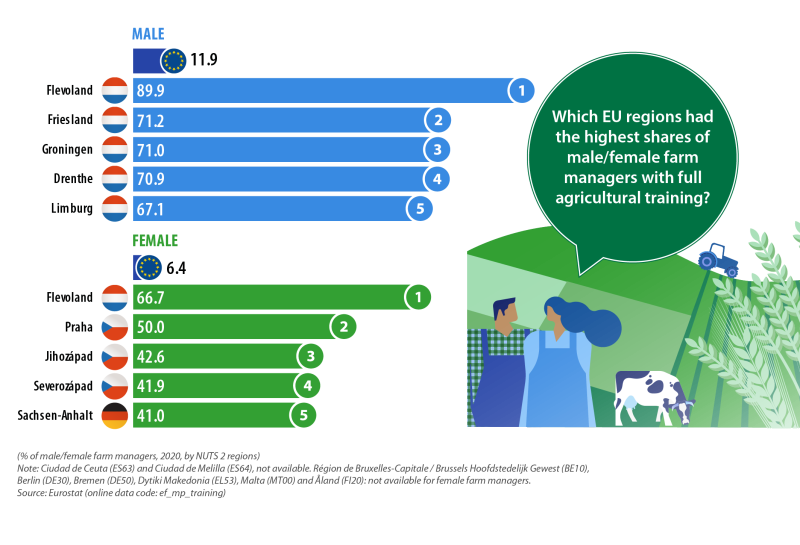

Across the EU, the Dutch region of Flevoland had the highest shares of farm managers with full agricultural training: in 2020, two thirds (66.7 %) of its female farm managers and nine tenths (89.9 %) of its male farm managers were fully trained.

In 2020, there were two regions in the EU where more than half of the total number of persons employed were active within agriculture, forestry and fishing: they were both located in eastern Romania – Neamţ (51.4 %) and Vaslui (61.7 %).

In 2020, there were approximately 9.1 million farms in the European Union (EU). Together, they used 1.55 million km² of land, almost two fifths (37.8 %) of the EU’s total land area. These headline figures underline the important impact that farming can have on natural environments, natural resources and wildlife. Indeed, farm managers within the EU are increasingly being encouraged to manage the countryside as a public good, so that the whole of society may benefit.

Farms in the EU fulfil a vital role in providing safe and affordable food. Agricultural products, food and culinary traditions are a major part of the EU’s regional and cultural identity. This is, at least in part, due to a diverse range of natural environments, climates and farming practices that feed through into a wide array of agricultural products.

From a statistical perspective, this edition of the Eurostat Regional Yearbook marks a milestone insofar as it publishes data from the latest agricultural census. Every 10 years, in accordance with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), EU Member States carry out an agricultural census. The latest of these was conducted in 2020/2021. It covers approximately 300 variables, with the information collected spanning a broad range of topics, including: general characteristics of the farm and the farm manager; land use and livestock; the agricultural labour force; animal housing and manure management; and support measures for rural development. Data from the census may help frame policy debates, answering questions such as:

- Who will farm in the future given the large share of older farm managers?

- How many women are farming?

- Is agriculture becoming dominated by big business?

- Is organic farming expanding?

It is important to note that the agricultural census took place during the COVID-19 crisis. While this had a direct impact on various aspects of data collection (for example, the preparation and running of data collection instruments or the selection of human resources to carry out the census), many statistical offices rapidly adapted their working practices to make use of alternative methods (telephone or online surveys; additional use of administrative sources). While these changes undoubtedly brought benefits and ensured the census was conducted according to schedule, they may have impacted on the quality of results when compared with ‘normal’ circumstances (for example, due to lower response rates or more room for misunderstanding complex technical questions). Finally, the pandemic – as with practically all sectors of society – had a direct impact on the agricultural sector and farming communities. Given the vast majority of variables collected in an agricultural census refer to the structure of farms (rather than the annual output of crops and livestock), it is likely that COVID-19 had a relatively small impact on most of the results. Nevertheless, this is something to bear in mind when interpreting results from the 2020 census, in particular those for variables that are related to labour force or to other gainful activities.

Within the context of the 2023 European Year of Skills, the infographic above depicts EU regions with the highest proportions of female and male farm managers having undertaken full agricultural training. On average, some 6.4 % of female farm managers in the EU met this criterion, while a somewhat higher share was recorded for male farm managers (11.9 % had undertaken full training). An analysis of NUTS level 2 regions reveals that Flevoland in the Netherlands had the highest share of farm managers with full agricultural training. This was the case for female farm managers (two thirds or 66.7 % had undertaken full agricultural training) and for male farm managers (nine tenths or 89.9 % had undertaken full agricultural training).

The final chapter in this publication presents regional agricultural statistics. It focuses on three principal subjects:

- the agricultural labour force, with a special focus on farm managers (analysed by sex and age);

- farms, analysed by size and by specialisation;

- the economic accounts for agriculture that provide information on the performance of agricultural activity, through the ratio of intermediate consumption to output and the share of total value added from agriculture in all economic activities across the EU economy.

Full article

Farm managers and the agricultural labour force

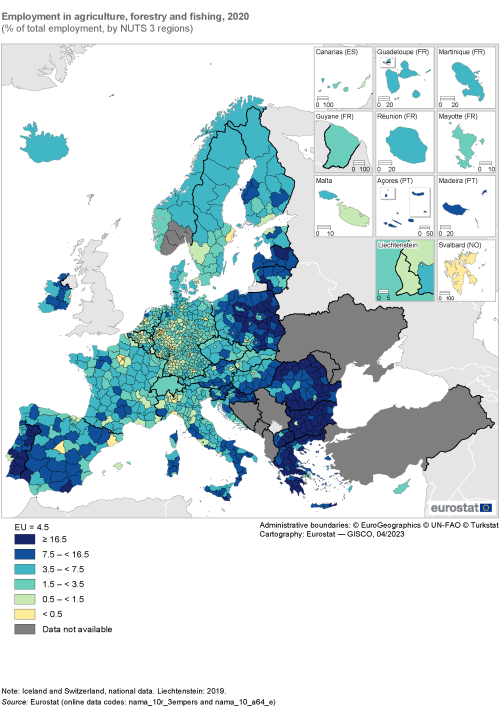

In 2020, some 4.5 % of the EU’s total employment – an estimated 9.4 million people – worked within the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector. The vast majority of these, 4.2 % of total employment, worked in agriculture. Data at the most detailed regional level (NUTS level 3 regions) are only available for the aggregate covering the whole of agriculture, forestry and fishing.

For many, working on a farm is a part-time or seasonal activity. These people – often family members of the holder – provide help during peak periods of activity that are generally linked to the harvest. As such, the formal count of employment – based on the number of employees and self-employed persons – may be considerably lower than the total number of agricultural workers (which may include family members of the holder, part-time and seasonal workers, or casual labour).

Leaving aside these caveats, the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector was an important source of employment for a large number of regions across eastern and southern EU Member States; this was particularly the case in Bulgaria, Greece, Poland, Portugal and Romania (see Map 1). There were 114 NUTS level 3 regions where at least 16.5 % of people employed were working within the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector in 2020 (as shown by the darkest shade in the map). This group included all but three of the 28 regions in Bulgaria – the exceptions being the capital region of Sofia (stolitsa), Varna and Gabrovo. It also included a large concentration of regions in neighbouring Romania, where 24 out of 42 regions reported at least 16.5 % of total employment in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector. A closer analysis reveals there were several regions in Romania where agriculture, forestry and fishing provided work to almost half of the workforce, with this share reaching a peak in the eastern regions of Neamţ (51.4 %) and Vaslui (61.7 %); these were the only NUTS level 3 regions to report that more than half of employed persons worked in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector.

In absolute terms, the highest regional counts for persons employed within the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector were principally located in Romania. There were five NUTS level 3 regions in eastern Romania where upwards of 100 000 persons were employed in this sector – the only regions in the EU above this level, peaking at 146 200 persons in Iaşi. Sandomiersko-jędrzejowski (south-east Poland) and Almería (southern Spain) were the only regions outside of Romania to feature among the 10 NUTS level 3 regions with the highest employment counts within the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector. Almería is characterised by intensive agriculture: it has the highest concentration of greenhouses in the world, primarily growing out-of-season vegetables with hydroponic technology.

The regional distribution of employment within the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector was relatively skewed insofar as more than three fifths of NUTS level 3 regions – or 706 out of 1 166 regions – reported a share below the EU average. At the bottom end of the range, there were 137 regions in 2020 where less than 0.5 % of the total number of persons employed were working in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector. They included 13 predominantly urban regions where the share was 0.0 %, including the capital regions of Belgium, Denmark and Germany, as well as three regions within close proximity of the French capital.

(% of total employment, by NUTS 3 regions)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10r_3empers) and (nama_10_a64_e)

Farm managers

Farm managers are the people responsible for the normal daily financial and production routines of running a farm, such as what and how much to plant or rear and what labour, materials and equipment to employ. Often the farm manager is also the owner (otherwise referred to as the ‘holder’) of the farm but this need not be the case, especially when the farm has a separate legal identity.

The vast majority of farms in the EU are small, semi-subsistence farms. Often the farm managers of these agricultural holdings continue to work part-time long after the normal retirement age, to provide in part for their own needs. Some older farm managers may face difficulties in encouraging younger generations to take over family farms, as they may have negative perceptions concerning careers in agriculture and prefer to look elsewhere for work in other sectors . As a result, the agriculture sector is characterised by slow generational renewal and a relatively high average age of farm managers; these characteristics are widespread across most EU Member States.

Some 6.5 % of farm managers in the EU were aged less than 35 years

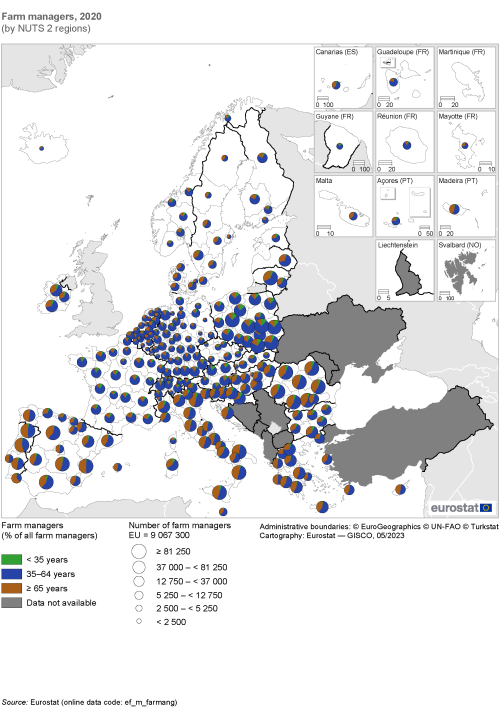

Access to finance, land, capital and knowledge are particular concerns for many young people considering working in agriculture. With this in mind, the EU is stepping up its efforts to encourage younger people into farming, by providing help to get their business off the ground with start-up grants, income support and benefits such as additional training. Map 2 provides information on the number of farm managers across NUTS level 2 regions, detailing the share of farm managers for three broad age groups. In 2020, 6.5 % of farm managers in the EU were young farmers – defined here as those under the age of 35 years. By contrast, approximately one third (33.2 %) of farm managers were at least 65 years of age.

The highest proportions of young farm managers were recorded in regions across France, Austria and Poland. In 2020, the French island region of Corse had the highest share, with 14.5 % of its farm managers under the age of 35; it was closely followed by Oberösterreich in northern Austria (14.4 %). At the other end of the scale, there were three regions in Portugal – Algarve, Centro and Norte – where more than half of all farm managers were aged 65 years or over; the highest share was observed in Algarve (60.7 %). Comunitat Valenciana in Spain was the only other region in the EU to record a majority (50.1 %) of its farm managers aged 65 years or over.

Farm managers with full agricultural training

Agricultural holdings take many different forms across the EU: from large-scale, intensive farms that cover large swathes of land to very small, semi-subsistence holdings. There is often a difference in the ownership and management of these different types of farm: the former may be owned by large enterprises that install professionally-trained managers, whereas the latter are more likely to be family-owned and run.

Generational renewal among farm managers has become a crucial issue. It is often compounded by labour shortages in the wider farm labour force that are increasingly apparent at harvest time across many regions of the EU. A new generation of farm managers may be expected to have the necessary skills to: produce more efficiently, while protecting the environment; contribute to efforts related to climate change; meet society’s demands regarding healthy, balanced diets and animal welfare; keep up with increasingly rapid scientific and technological progress. With a more qualified workforce, the agriculture sector may be in a position to increase its productivity and income-generating capabilities. To do so, some farm managers and members of the wider farm labour force will likely need to increase their skill levels, for example learning how to use emerging digital technologies, becoming data analysts, or rural innovators.

A farm manager is considered to have full agricultural training if they have taken and completed a training course for the equivalent of at least two years full-time training after the end of compulsory education. The course – in agriculture, horticulture, viticulture, silviculture, pisciculture, veterinary science, agricultural technology or an associated subject – should be at an agricultural college, university or other institute of higher education. The common agricultural policy places strong emphasis on knowledge sharing and innovation. It provides for specific measures to help farm managers access advice and training throughout their working lives. Support is also provided for innovation via the European innovation partnership network.

In 2020, some 923 000 (or 10.2 %) of the EU’s 9.1 million farm managers had received full agricultural training. By contrast, 17.5 % had followed a basic level of training, with an overwhelming majority (72.4 %) relying on practical experience. A more detailed analysis for NUTS level 2 regions shows there were substantial regional variations in the share of farm managers with full agricultural training. More than half of all farm managers had received full agricultural training across every region of Luxembourg and the Netherlands. By contrast, this share was no higher than 1.5 % for every region of Greece and Romania.

There were 16 NUTS level 2 regions across the EU where at least 50.0 % of farm managers had received full agricultural training in 2020 (as shown by the darkest shade in Map 3). The highest regional share (89.1 %) was recorded in the Dutch region of Flevoland; there were also particularly high shares recorded in three other regions from the (north of the) Netherlands – Friesland, Groningen and Drenthe. The rest of this group was composed of the eight remaining regions in the Netherlands, Luxembourg, as well as three regions in France – Bretagne, Picardie and Ile-de-France.

At the other end of the scale, there were 24 NUTS level 2 regions where fewer than 1.5 % of farm managers in 2020 had received full agricultural training (as shown by the lightest shade in Map 3). This group included: all eight regions of Romania; 12 out of the 13 regions in Greece (the exception being the capital of Attiki; with a share that was narrowly higher, at 1.5 %); four island regions, namely, Região Autónoma da Madeira (Portugal), Mayotte (France), Cyprus and Malta.

(% of all farm managers, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (ef_mp_training)

Farms

Close to one third of all the EU’s farms were located in Romania

In 2020, there were 9.1 million agricultural holdings in the EU. Romania had, by far, the largest number of farms among EU Member States, at 2.9 million; it accounted for almost one third (31.8 %) of the total number of farms in the EU. This share was more than twice the share recorded in Poland (14.4 % of the EU total), while there were also double-digit shares in Italy (12.5 %) and Spain (10.1 %). These figures underline the structural differences in agricultural holdings, with small, semi-subsistence and family farms predominating, particularly in eastern and southern Member States.

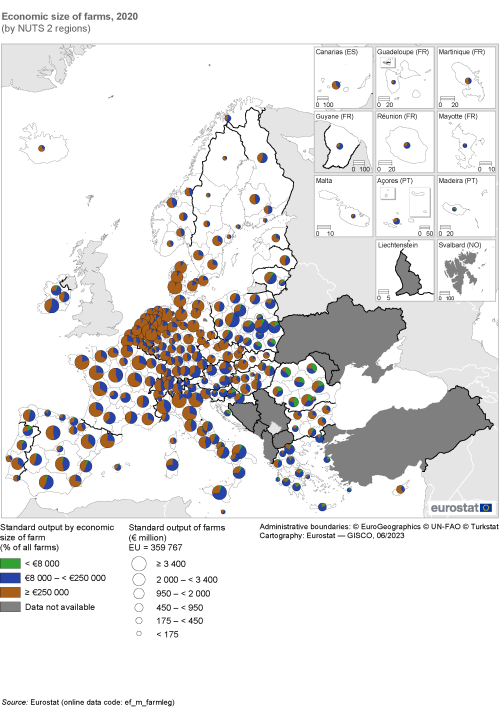

Standard output is an economic measure, defined as the average value of agricultural output at farm-gate prices. In 2020, 5.9 million farms in the EU had a standard output that was below €8 000, accounting for almost two thirds (65.6 %) of all farms. Almost one third of EU farms (2.8 million or 31.2 %) had a standard output within the range of €8 000–€250 000. By contrast, there were relatively few (294 200) farms with a standard output of at least €250 000; they accounted for 3.2 % of the total number of farms in the EU.

The size of each circle in Map 4 is related to the standard output of each NUTS level 2 region. In 2020, Andalucía in southern Spain had the highest level of standard output, at €11.2 billion. It was followed by the northern Italian region of Lombardia (€9.4 billion) and the western French region of Bretagne (€7.5 billion). There were 25 regions within the EU that had a standard output of at least €3.4 billion – as shown by the largest circles in the map. These were principally located in France (seven regions), Italy (six regions) and Spain (five regions), with two regions from each of the Netherlands and Poland, and single regions from each of Denmark, Germany and Ireland.

Map 4 provides an alternative analysis based on standard output. In 2020, the relatively small number of large farms – with a standard output of at least €250 000 – accounted for almost three fifths (58.6 %) of the EU’s total agricultural output. This pattern was repeated in a majority of EU regions, as a relatively small number of large farms often accounted for more than half of each region’s agricultural output (as shown by the brown pie slices). At the other end of the scale, the high number of small farms – with a standard output of less than €8 000 – together accounted for just 3.7 % of the EU’s total agricultural output. It should be noted that these small (often semi-subsistence) farms can play a key role in reducing the risk of rural poverty, for example, providing food and additional sources of income to farming families.

Almost three fifths of the EU’s farms were specialist crop farms

Historically, small family-run farms were largely diversified units with a mix of livestock, fruit, vegetables and other crops. With the introduction of machinery and equipment, there was a general move towards greater specialisation, with an increasing number of hectares being farmed in an efficient manner to provide food for rapidly expanding populations, with a particular focus on maximising yields. Farm managers continue to use their knowledge of the climate and agronomic factors (like the soil), among others, to determine what to grow or what animals to rear, increasingly assisted by information and communication technologies. While this lends itself to a certain concentration of dominant farm types, greater emphasis has been placed on farm owners as custodians of the countryside and sustainability. The sustainable development of agriculture aims to optimise yields and farm income, while minimising resource consumption and environmental impact (for example, improving the quality of soils or water, or increasing biodiversity). Farm managers today increasingly explore alternative production methods and a range of other gainful activities, such as forestry, tourism, or environmental services.

A farm typology may be created from the classification of agricultural holdings based on their standard output, calculated for each crop and animal. Farm specialisation describes those holdings that have a single dominant activity: an agricultural holding is said to be specialised when a particular activity provides at least two thirds of its production. Farm diversification is the opposite: it refers to a situation when an agricultural holding gains income from diverse activities. At its most simple level, this typology may be used to identify the following general types of farm [1]:

- agricultural holdings where crop production is the dominant activity – crop specialists;

- agricultural holdings where livestock production is the dominant activity – livestock specialists;

- agricultural holdings where neither crop nor livestock production is the dominant activity – mixed farms.

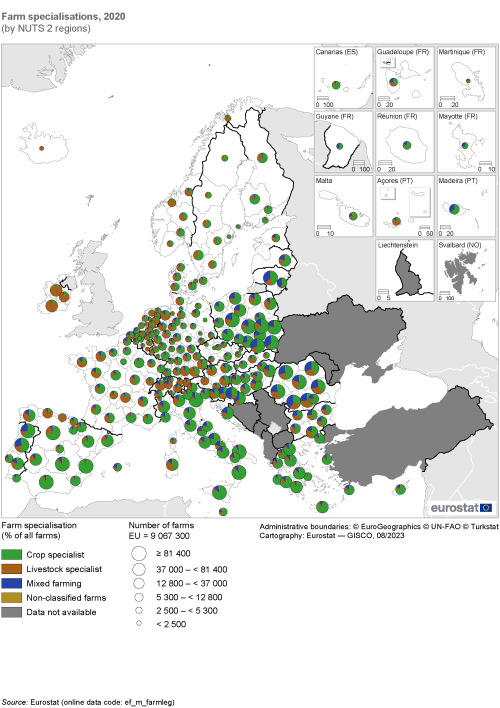

In 2020, almost three fifths (58.2 %) of EU farms were categorised as specialist crop farms. The most common forms included: general field cropping (18.5 % of all farms); specialist cereals, oilseed and protein crops (15.9 %); and specialist olives (8.9 %). Slightly more than one fifth (21.7 %) of the EU’s farms were specialist livestock farms, with specialisation in dairying (5.2 %) and cattle-rearing and fattening (4.3 %) being the most common forms. Mixed farms, comprising farms with crops and livestock or various types of crops or various types of livestock, accounted for just under one fifth (19.3 %) of all farms in the EU. A small number of farms (0.8 % of the total) could not be classified because they are subsistent in nature or because they produce goods for which no standard output can be calculated.

Map 5 confirms that a majority of the farms in the EU were crop specialists. In 2020, there were 156 NUTS level 2 regions (out of 240 for which data are available) where crop specialists accounted for at least 50.0 % of all farms. By contrast, there were 37 regions where livestock specialists accounted for at least half of all farms and no regions where mixed farms did so.

A more detailed analysis reveals there were several NUTS level 2 regions in the EU where almost all (or indeed all) farms were classified as crop specialists in 2020. Several of these were capital regions characterised by very small agricultural sectors, often with a high degree of specialisation in horticulture. Leaving these aside, there were four regions in southern EU Member States where crop specialists accounted for more than 9 out of 10 farms (each of which had a relatively high number of farms that were specialist olive producers):

- Comunitat Valenciana and Andalucía in Spain;

- Peloponnisos in Greece; and

- Puglia in Italy.

Regions with a high share of livestock specialists are often characterised by a temperate climate and relatively high levels of rainfall (favouring the production of grassland/pasture). There were nine NUTS level 2 regions in the EU where livestock specialists accounted for at least four fifths of all farms in 2020:

- all three regions of Ireland;

- three Alpine regions in westernmost Austria – Salzburg, Tirol and Vorarlberg;

- Cantabria in north-west Spain;

- Friesland in the Netherlands; and

- Prov. Luxembourg in Belgium.

Economic accounts for agriculture

The economic accounts for agriculture provide an overall picture of the performance of agricultural activity. The performance of farming matters as it is often the cornerstone of rural communities, upon which ‘upstream’ sectors (such as animal healthcare providers and wholesalers of agricultural inputs) and ‘downstream’ sectors (such as food processing, packaging and transport businesses) may depend.

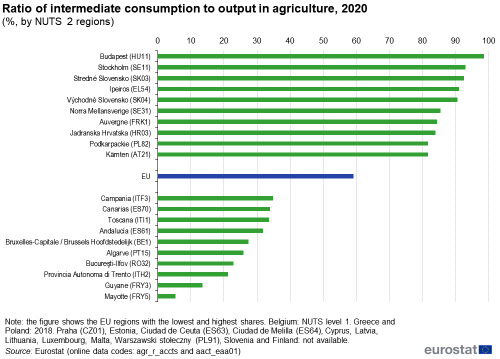

Intermediate consumption

At the start of the production process, agricultural holdings generally have to make purchases of goods and services that are used as inputs; among other products, they buy goods such as fuel, seeds, fertilisers, plant protection products and animal feedingstuffs or services such as veterinary services. The expenditure on these non-labour inputs is termed ‘intermediate consumption’ expenditure. Across the EU, agricultural intermediate consumption was valued at €236.4 billion in 2020. This was equivalent to 59.2 % of the gross value of agricultural output.

Figure 1 shows the ratio of intermediate consumption to agricultural output, highlighting the 10 NUTS level 2 regions with the highest and lowest ratios. Excluding the atypical cases of the French outermost regions of Mayotte and Guyane, most of the regions with the lowest ratios of intermediate consumption to output in 2020 were located in southern EU Member States. The only exceptions were the Belgian and Romanian capital regions (where agriculture plays an inconsequential role in the local economy). The relatively low ratios observed for the southern regions shown in the bottom half of Figure 1 likely reflect the nature of their agricultural practices, with small (often semi-subsistence) farm holdings predominating, whereby farms operate with little capital and tend to be labour intensive. This group included Provincia Autonoma di Trento, Toscana and Campania (all in Italy), Andalucía and Canarias (both in Spain), as well as Algarve (in Portugal).

In 2020, the ratio of intermediate consumption to agricultural output peaked in the Hungarian and Swedish capital regions of Budapest (98.6 %) and Stockholm (93.0 %); as mentioned above, agriculture accounts for a tiny proportion of overall economic activity in most capital regions. The ratio of intermediate consumption to output was also very high in two Slovak regions – Stredné Slovensko (92.5 %) and Východné Slovensko (90.6 %) – while Ipeiros in Greece (91.0 %; 2018 data) was the only other region to record a ratio of more than 86 %.

(%, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (agr_r_accts) and (aact_eaa01)

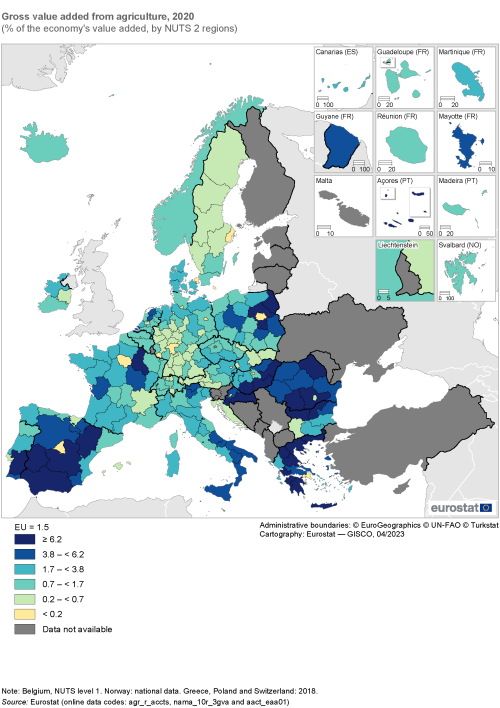

Gross value added from agriculture

Gross value added is the difference between the value of output and intermediate consumption, adjusted for taxes less subsidies on products. In 2020, the gross value added of the EU’s 9.1 million farms was €178.5 billion. To put this figure into context, it was equivalent to 1.5 % of total value added from all activities in the EU economy.

Agriculture’s contribution to regional value added has been falling over a relatively lengthy period of time. That said, there were a number of rural regions across the EU where the economic importance of farming in 2020 was considerably higher than the EU average (see Map 6; note that data for Belgium relate to NUTS level 1 regions). These regions were usually located in southern and eastern regions of the EU and were often characterised by fertile plains that are suited to growing crops.

In 2020, there were 25 NUTS level 2 regions where gross value added from agriculture accounted for at least 6.2 % of total economic performance (as shown by the darkest shade). The relative economic importance of agriculture was particularly high in the Bulgarian region of Severozapaden (where farming accounted for 13.4 % of total value added); it was followed by two regions from Greece (2018 data): Thessalia (12.4 %) and Peloponnisos (11.4 %). Within this group of 25 regions, there were three more where agriculture had a double-digit share of regional economic performance: Severen tsentralen (Bulgaria; 10.2 %), Alentejo (Portugal; 10.2 %) and Panonska Hrvatska (Croatia; 10.1 %). Note that Champagne-Ardenne in France – which is a major producer, among other products, of cereals, sugar beet, grapes and vegetables – was the only region from western or northern EU Member States to be present within this group as agriculture contributed 6.6 % of its regional gross value added.

In 2020, there were 15 regions where gross value added from agriculture accounted for less than 0.2 % of total economic performance (as shown by the lightest shade in Map 6). The economic importance of agriculture was usually very low in capital regions, as land is at a premium. This pattern may also be influenced, at least to some degree, by the administrative boundaries used to demarcate regions, as capitals tend to cover relatively small areas of land. The group of 15 regions where agriculture accounted for less than 0.2 % of regional value added included the capital regions of Belgium (NUTS level 1), Denmark, Germany, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Hungary, Austria, Poland (2018 data) and Sweden; it was completed by four German regions – Bremen, Hamburg, Darmstadt and Saarland.

(% of the economy’s value added, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (agr_r_accts), (nama_10r_3gva) and (aact_eaa01)

Source data for figures and maps

Data sources

Agricultural census

An agricultural census is carried out every 10 years. The most recent census was conducted during 2020 and/or 2021; this is the first edition of the Eurostat Regional Yearbook to publish information from the latest edition of this rich and varied data source. Data from an agricultural census may be complemented with information from farm structure surveys (FSS) that are conducted each three or four years in-between censuses; together, these two data sources provide information for structural agricultural statistics.

The latest agricultural census covers EU Member States, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland; limited data were also received from a number of candidate countries. The census is based on the collection of statistics from individual agricultural holdings. It covers a range of subjects: general characteristics of farms and farm managers; land use; livestock; the agricultural labour force; animal housing and manure management; and rural development support measures. The latest census collected information for approximately 300 different variables.

The legal basis for the collection of data is provided by Regulation (EU) No 2018/1091 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 July 2018 on integrated farm statistics. It defines a list of core variables, alongside more extensive provisions to collect additional variables through a set of modules as defined within Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1874 of 29 November 2018.

The core variables collected by the agricultural census include the location of the holding, legal personality of the holding, manager, type of tenure of the utilised agricultural area, land use indicators, organic farming, irrigation on cultivated outdoor area, livestock indicators, and organic production methods applied to animal production. A module on the labour force and other gainful activities covers farm management, the family labour force, the non-family labour force, other gainful activities directly and not directly related to the agricultural holding. The module for rural development covers support received by agricultural holdings through various rural development measures. The module for animal housing and rural development covers animal housing, nutrient use and manure on the farm, manure application techniques, facilities for manure.

Each country is allowed, in line with the legislation, to set up thresholds that may exclude very small holdings, as long as the conditions for minimum coverage are guaranteed. The standard threshold for the utilised agricultural area is five hectares, while that for livestock is 1.7 livestock units. Regulation (EU) 2018/1091 ensures that the statistics provided should cover at least 98 % of national utilised agricultural area (excluding kitchen gardens) and at least 98 % of national livestock units (LSU); where this is not the case, countries may extend their survey frames by establishing lower and/or additional thresholds.

Data from the agricultural census may be used by the public, researchers, farm owners, farm managers and policymakers to understand better the state of EU farming and the impact of agriculture on the environment. These statistics track changes in the agricultural industry and provide a basis for decision-making within the common agricultural policy (CAP) and other EU policy areas.

Economic accounts for agriculture

Economic accounts for agriculture (EAA) provide detailed information on the economic performance of agriculture. The purpose of these statistics is to analyse the production process of the agricultural industry and the primary income generated by this production. Regional EAA are presented in current prices, their main indicators include: the value of output (measured in both producer prices and basic prices), intermediate consumption, subsidies and taxes, consumption of fixed capital, rent and interest, and capital formation. Regional EAA are generally compiled by EU Member States for NUTS level 2 regions (there are some exceptions); these statistics are provided on the basis of a gentlemen’s agreement for 2020.

Indicator definitions

Employment

Many farm managers and farm workers pursue agriculture as a part-time activity, with a relatively high proportion of farms being family-run (with family members of the holder providing help at various times of the year, reflecting seasonal peaks that are often linked to harvesting). Four distinctions can be made when considering labour input within the agriculture sector: i) agricultural employment; ii) the regular agricultural labour force; iii) the volume of agricultural work carried out; and iv) farm managers.

Employment data for agriculture, forestry and fishing are also available from national accounts; this source can be used for comparisons to be made across different sectors of the economy. These data cover employees and self-employed persons.

Farm manager

A farm manager is the natural person responsible for the normal daily financial and production routines of running an agricultural holding. Agricultural holdings normally have only one manager but it is possible for there to be co-managers, for example if the holder shares the management with a spouse or other family member.

Training levels

Agricultural training is thought to have, among other outcomes, an influence on the environmental impact of farming. The highest level of agricultural education obtained by a farm manager is classified according to one of three different categories:

- only practical agricultural experience – if the manager’s experience was acquired through practical work on an agricultural holding;

- basic agricultural training – if the manager took any training courses completed at a general agricultural college and/or an institution specialising in certain subjects (including horticulture, viticulture, silviculture, pisciculture, veterinary science, agricultural technology and associated subjects); a completed agricultural apprenticeship is regarded as basic training;

- full agricultural training – if the manager took (and completed) any training course

- in agriculture, horticulture, viticulture, silviculture, pisciculture, veterinary science, agricultural technology or an associated subject,

- continuously for the equivalent of at least two years full-time training after the end of compulsory education,

- at an agricultural college, university or other institute of higher education.

Standard output by economic size of farm

The standard output of an agricultural product (a crop or livestock) is the average monetary value of output at farm-gate price, in euro (€). It is expressed per hectare for crops or per head of livestock. There is a regional coefficient for each product, which is defined as the average value over a five-year reference period. By summing standard outputs per hectare of crop and per head of livestock, the overall economic size of a farm may be determined.

Farm specialisations

Some farms earn their income from a range of diverse activities (mixed farming), while others may specialise in crops or livestock. Farm specialisation describes the dominant activity in farm income: an agricultural holding is said to be specialised when a particular activity provides at least two thirds of its standard output.

Intermediate consumption

Intermediate consumption covers purchases made by farms for raw and auxiliary materials that are used as inputs for crop and animal production; it also includes expenditure on veterinary services, repairs and maintenance, and other services. It does not include compensation of employees (payments of wages and salaries and social security contributions), nor financial cost (such as interest payments) or investment (although it does include costs for repair and maintenance).

Agricultural output and output of the agricultural industry

Agricultural output includes output sold (including trade in agricultural goods and services between agricultural units), changes in stocks, output for own final use (own final consumption and own-account gross fixed capital formation), output produced for further processing by agricultural producers, as well as intra-unit consumption of livestock feed products. Animal and crop output are the main product categories of agricultural output.

The output of the agricultural industry is composed of the sum of agricultural output as well as goods and services produced in inseparable non-agricultural secondary activities.

Gross value added

Gross value added is the difference in basic prices between the value of output of the agricultural industry and the value of intermediate consumption.

Context

Common agricultural policy (CAP)

The CAP is one of the EU’s oldest policies, supporting agriculture and contributing to Europe’s food security. It aims to:

- support farms and improve agricultural productivity, so that consumers have a stable supply of affordable food;

- ensure that EU farmers can make a reasonable living;

- help tackle climate change and the sustainable management of natural resources;

- maintain rural areas and landscapes across the EU;

- keep the rural economy alive promoting jobs in farming, agri-foods industries and associated sectors.

The CAP has three elements:

- income support – direct payments ensure income stability, and remunerate farms for environmentally friendly farming and delivering public goods not normally paid for by the market, such as taking care of the countryside;

- market measures – the EU can take measures to deal with difficult market situations such as a sudden drop in demand due to a health scare, or a fall in prices as a result of a temporary oversupply;

- rural development measures – national and regional programmes address the specific needs and challenges facing rural areas.

At the end of 2021, a political agreement was reached on a new common agricultural policy for the period 2023–2027. At the same time, each EU Member State was required to submit a CAP strategic plan; these were assessed by the European Commission.

Regulation (EU) 2021/2116 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 December 2021 on the financing, management and monitoring of the common agricultural policy entered into force at the start of 2023 and is designed to make the CAP more responsive to future challenges, while continuing to support EU farms for a sustainable and competitive agricultural sector. This modernised agricultural policy is built around 10 specific objectives that are focused on social, environmental and economic goals: to ensure a fair income for farms; to increase competitiveness; to improve the position of farms in the food chain; climate change action; environmental care; to preserve landscapes and biodiversity; to support generational renewal; vibrant rural areas; to protect food and health quality; fostering knowledge and innovation. At the end of 2023, the European Commission will submit a report, providing an annual performance review of the strategic plans.

In total, €387 billion of funding has been budgeted for the CAP as part of the EU’s long-term budget, the multiannual financial framework (2021–2027). This comes from two different funds: €291 billion from the European agricultural guarantee fund (EAGF) and €96 billion from the European agricultural fund for rural development (EAFRD), the latter including €8 billion allocated as part of the European Recovery Instrument (also known as NextGenerationEU) designed to support EU Member States to recover, repair and emerge stronger from the COVID-19 crisis. With respect to agriculture, this funding is intended to help farms and rural areas to deliver a green transition, while providing support for reforms considered essential to Europe’s ambitious environmental targets.

European Green Deal

A European Green Deal is the EU’s strategy for sustainable growth; it aims to turn climatic and environmental challenges into opportunities for a broad range of policy areas. The Green Deal aims to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. The CAP plays a part in this transition, as approximately 40 % of its budget is climate-relevant.

The European agriculture and food system, supported by the CAP, is already a global standard in terms of safety, security of supply, nutrition and quality. New policy developments are designed to ensure that the EU’s agriculture sector becomes a global standard for sustainability, bringing environmental, health and social benefits, by encouraging farm managers to contribute towards its climatic and environmental ambitions. The EU’s goals are:

- to ensure food security in the face of climate change and biodiversity loss;

- reduce the environmental and climate footprint of the EU’s food system;

- strengthen the resilience of the EU’s food system;

- lead a global transition towards competitive sustainability from farm to fork.

In May 2020, the European Commission released a staff working document that provided an Analysis of links between CAP Reform and Green Deal (SWD(2020) 93 final). At the same time, the Commission adopted a farm to fork strategy, a biodiversity strategy, an action plan for the circular economy, and a proposal for a climate law. European Commission services identified potential obstacles and/or gaps jeopardising the European Green Deal and laid out a number of steps needed to fully align the CAP with it (and its associated strategies).

Farm to fork strategy

The EU’s A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system (COM(2020) 381 final) lies at the heart of the European Green Deal. It has a number of wide-ranging aims to: reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the consumption of natural resources; protect the environment and reverse biodiversity loss; promote fairer economic returns for those in the supply chain (particularly primary producers); and increase the level of organic farming.

With this in mind, the strategy includes a number of targets designed to transform food systems across the EU by 2030, for example it aims at: a 50 % reduction in the use of chemicals and more hazardous pesticides; a 20 % reduction in the use of fertilisers; and increasing the share of agricultural land in the EU used for organic farming to at least 25 %. By making food systems environmentally friendlier, fairer, healthier and more sustainable, the EU’s farm to fork strategy seeks to accelerate this transition.

Direct access to

Notes

- ↑ These statistics may be further disaggregated, for example looking in more detail at crop specialists to identify those farms that specialise in cereals, root crops, field vegetables, permanent crops, fruit, horticulture and so on.

- Agricultural production – crops

- Agricultural production – livestock and meat

- Livestock and meat production statistics

- Farmers and the agricultural labour force – statistics

- Milk and milk product statistics

- Performance of the agricultural sector

- Developments in organic farming

- Fully organic farms in the EU

- Key figures on the European food chain – 2022 edition

- Eurostat regional yearbook – 2023 edition

Online publications

- Regional agriculture statistics (t_reg_agr)

- Agriculture (t_agr), see:

- Economic accounts for agriculture (t_aact)

- Regional agriculture statistics (reg_agr)

- Structure of agricultural holdings (reg_ef)

- Economic accounts for agriculture by NUTS 2 regions (agr_r_accts)

- Agriculture (agr), see:

- Farm structure (ef)

- Main farm indicators by NUTS 2 regions (ef_mainfarm)

- Management and practices (ef_mp)

- Economic accounts for agriculture (aact)

- Economic accounts for agriculture (aact_eaa)

- Agricultural labour input statistics (aact_ali)

Manuals and further methodological information

- Agricultural statistics – methodology

- Methodological manual on territorial typologies – 2018 edition

- Statistical regions in the European Union and partner countries – NUTS and statistical regions 2021 – 2020 edition

- Strategy for agricultural statistics for 2020 and beyond

Metadata

- Economic accounts for agriculture (ESMS metadata file – aact_esms)

- Farm structure (ESMS metadata file – ef_sims)

Surveys on economic accounts for agriculture are governed by:

- Regulation (EC) No 138/2004 of 5 December 2003 on the economic accounts for agriculture in the Community, amended on seven different occasions. Note that the provision of regional data is based on a gentlemen’s agreement.

Surveys on the structure of agricultural holdings are governed by:

- Regulation (EC) No 2018/1091 of 18 July 2018 on integrated farm statistics

- Summaries of EU Legislation: EU integrated farm statistics

- Agriculture and rural development (European Commission – Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development)

- European Commission – Agriculture and Rural Development – Financing the common agricultural policy

- European Commission – Food, Farming, Fisheries, see:

- European Commission – Geographical indications and quality schemes explained

- European Commission – The common agricultural policy: 2023–27

Maps can be explored interactively using Eurostat’s statistical atlas (see user manual).

This article forms part of Eurostat’s annual flagship publication, the Eurostat regional yearbook.