Archive:First and second-generation immigrants - statistics on education and skills

Data extracted in September 2016.

Planned article update: 17 November 2022.

Highlights

In 2014, over a third of first-generation immigrants with a tertiary degree worked in a job that did not require that level of education.

10 % of immigrants in the EU declare to know the language of their country of residence at basic level or less

- Authors: Mihaela Agafiţei, Georgiana Ivan

This article looks at educational skills of first- and second-generation immigrants, and compares them with the skills required at the work place or for getting a suitable job. Also, it looks at first- and second-generation immigrants and analyses their language skills in the main host country language . This article is part of an online publication First and second-generation immigrants - a statistical overview which contains data collected by Eurostat from the 2014 Labour Force Survey (LFS) ad-hoc module on the ‘Labour market situation of immigrants and their immediate descendants’.

Full article

General overview

The EU attracts quite a high proportion of highly skilled immigrants. At EU level, the highest proportion of tertiary graduates was observed among second-generation immigrants, especially those of EU origin: it was 11.5 percentage points (pp) more than among native-born residents with native backgrounds. Patterns vary across countries, but in most countries at least one of the two migration generations outperforms native-born residents with native backgrounds; only in very few cases does the opposite apply, i.e. is there a higher proportion of tertiary graduates among native-born residents of native background. Trends over time (between 2008 and 2014) show, in all five migration groups, an increase in the proportion of persons with a tertiary degree and a decrease in the proportion of persons with up to and including lower secondary education.

Younger people are more educated than older people in all five migration groups. There were no significant structural changes between 2008 and 2014, but the proportion of tertiary graduates increased and the proportion of those with primary education decreased in all three age groups and for all five migration groups.

There was a higher percentage of female than male tertiary graduates in every migration group. The same was true in 2008, but the gender gap had widened by 2014 for native-born residents of both foreign and native origin, sometimes quite considerably. For instance, for second-generation immigrants of non-EU origin it widened from 4.6 pp to 8.9 pp.

In 2014, over a third of first-generation immigrants with a tertiary degree worked in a job that did not require that level of education, against around a fifth of native-born residents with native backgrounds and second-generation immigrants. As compared with 2008, the proportion of over-qualified first-generation immigrants from outside the EU fell slightly, but there was a very strong increase in the proportion of over-qualified EU mobile citizens[1].

A slightly higher percentage of first- and second-generation immigrants of non-EU origin declare themselves to be over-qualified as compared with those of EU origin. The migration group with the lowest percentage (19.6 %)are second generation immigrants with at least one parent born in the EU

Around a third of immigrants move to countries in which their mother tongue is spoken, while another third (slightly more in the case of those born in another EU country) declare that they are proficient in the official language of the country they moved to. Only 9 % of those born in another EU country and 12% of those born in a non-EU country said they had only basic knowledge of the host country’s main language.

Educational attainment level

At EU level, the highest proportion of tertiary graduates was observed among second-generation immigrants, especially those of EU origin

People need skills and qualifications if they are to participate successfully in the labour market; this is particularly true for immigrants. Skills can be acquired through education and training (including training on the job). Data on qualifications, measured by highest level of educational attainment, are an important indicator of the skills on offer in the labour market, as they provide a wide range of information on individuals’ attributes and chances of getting a good job. The next section compares data on three aggregated levels of educational attainment[2] by those in the five main migration groups described above.

Highest level of educational attainment by migration status and background, at EU level

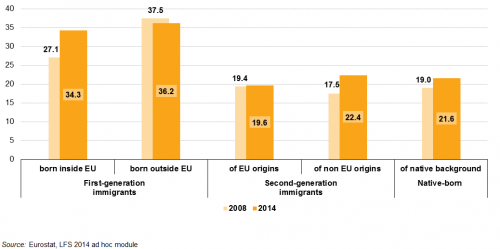

When we look at the highest level of educational attainment, we see significant differences between first- and second generation immigrants and native-born residents with native backgrounds (see Figure 2). In 2014, the highest proportion of tertiary graduates was observed among second-generation immigrants (38.5 % for those of EU and 36.2 % for those of non-EU origin), while the lowest was among first-generation immigrants born outside the EU (29.4 %). The proportion of tertiary graduates among EU mobile citizens was between that of native-born residents with foreign and those with native backgrounds. Overall, the EU attracts quite a high proportion of highly skilled immigrants.

The proportion of low skilled workers is particularly high (34.7 %) among first-generation immigrants born outside the EU, the same for native-born residents and EU mobile citizens (22.4 %), and lower for second-generation immigrants (16.1 % for those of EU and 18.9 % for those of non-EU origin).

The trend over time is similar for all groups, in line with the general increase in the proportion of tertiary graduates and a decrease in the proportion of those with up to lower secondary education. The biggest relative increase was among second-generation immigrants of both EU origin (+6.7 pp) and non-EU origin (+7.3 pp). The increase was similar (around +5 pp) for foreign-born and native-born residents of native origin.

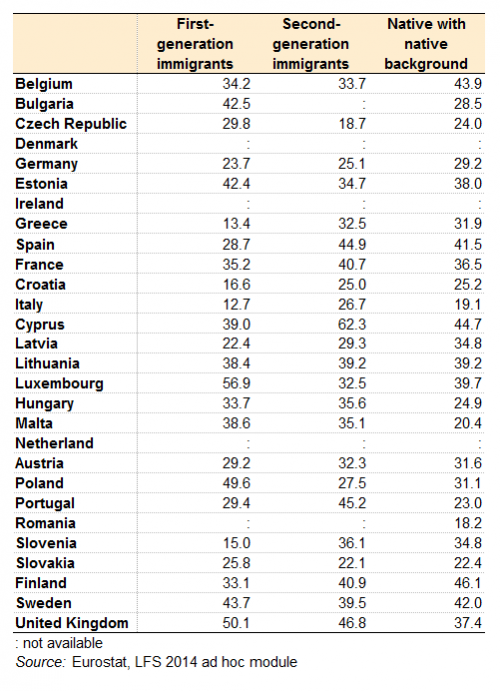

Highest level of educational attainment by migration status and background, by Member State [3]

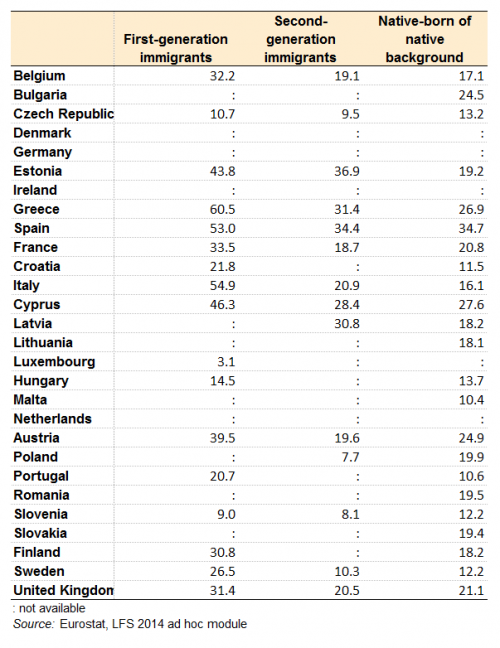

However, there are stark differences between Member States (Table 1). In seven of the 24 countries for which data are available for every migration group (Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Austria and Slovenia), the pattern is similar to that at EU level: the proportion of tertiary graduates is highest among second-generation immigrants, followed by native-born residents with native backgrounds and first-generation immigrants. In another set of countries (the Czech Republic, Estonia, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Sweden), first-generation immigrants outperform the other groups (by a considerable margin in the case of Luxembourg and Poland). The proportion of tertiary graduates is higher among native-born residents with native backgrounds than among the two generations in Belgium, Germany, Croatia, Latvia and Finland, and lower in Hungary, Portugal and the United Kingdom. It is striking that in Luxembourg (56.9 %) and the United Kingdom (50.1 %), over half of the foreign born residents aged 25 to 54 are tertiary graduates. Similarly, over half of the second-generation immigrants aged 25 to 54 living in Cyprus are tertiary graduates (62.3 %). In the United Kingdom, the proportion of tertiary graduates in both migration generations exceeds the corresponding proportion in the native population with native backgrounds. It is clear, therefore, that these countries attracted mostly highly skilled migrants. Conversely, in Belgium, although over 30 % of immigrants (regardless of migration generation) are tertiary graduates, this proportion is considerably smaller than that among native-born residents with native backgrounds (-9.7 pp for first-generation and -10.2 pp for second generation immigrants). In Lithuania, the proportion of tertiary graduates is almost the same in all three groups.

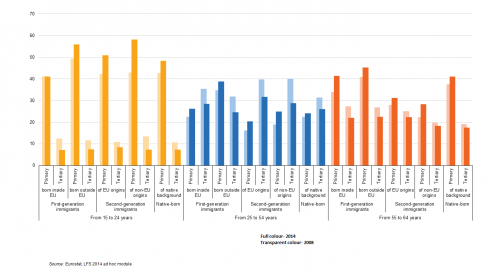

Highest level of educational attainment by age group[4], migration status and background

In 2014 (Figure 3), the proportion of tertiary graduates was higher (31.3 compared with 40.0 %) in the core working age group (aged 25 to 54) than among older (55 to 64 year old) workers (19.1 compared with 27.3 %), regardless of migration status and background. The percentage of tertiary graduates is less relevant for young workers (aged 15 to 24), as many will have not completed their studies. Therefore, younger people (aged 25 to 54) were more educated than older people (aged 55 to 64), in all five migration groups analysed. The highest proportions of tertiary graduates of core working age can be observed among second-generation immigrants (around 40.0 %), while the proportion of older tertiary graduates (aged 55 to 64) is highest among first-generation immigrants (around 27.0 %). This corresponds to the fact that, on average, the median age of second-generation immigrants tends to be lower than that of first generation immigrants and native-born residents with native backgrounds . In both age groups (core working age and older workers), the proportion of tertiary graduates is lowest among native-born residents of native background.

Comparing gaps in education level, we can see that, for 55 to 64 year-olds in all five migration groups, the proportion of those with primary education only is always greater than the proportion of tertiary graduates. As regards the core working age group (aged 25 to 54), except in the case of the first-generation immigrants born outside the EU, the ratio is reversed: the proportion of those with primary education only is always smaller than that of tertiary graduates[5]. In both age groups (core working age and older workers), the proportion of people with primary education only is lower among second-generation immigrants than for the other four migration groups. However, while for older workers (aged 55 to 64), the gap vis-à-vis tertiary graduates is only about +3 pp, it is just over -21.0 pp for the core working age group (aged 24 to 55).

No significant structural changes occurred between 2008 and 2014, but in all three age groups and all five migration groups, the proportions of tertiary graduates increased and the proportions of those with primary education only decreased.The largest increase in the proportion of tertiary graduates was among 25 to 54 year-old native-born residents of EU origin (+8.0 pp) and of non-EU origin (+11.2 pp) and the largest decrease in the proportion of those with primary education only was among 15 to 24 year-old native-born residents of both EU (-8.5 pp) and non-EU origin (-15.2 pp).

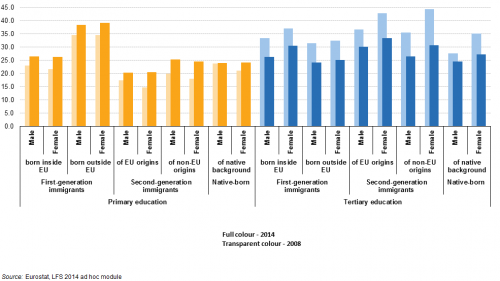

Highest level of educational attainment by sex, migration status and background

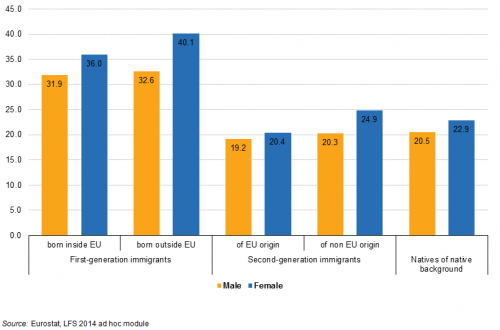

In the 25-54 age group, for all five migration groups analysed the proportion of tertiary graduates was higher among women than among men

In the 25-54 age group, for all five migration groups analysed the proportion of tertiary graduates was higher among women than among men (Figure 4). The difference is greatest among second-generation immigrants (6.1 pp for those of EU and 8.9 pp for those of non-EU origin) and lowest among first-generation immigrants born outside the EU (0.8 pp). In 2008, the pattern was the same (the percentage of tertiary graduates was higher among women than among men in every group), but the gender gap increased for natives (from 2.7 pp in 2008 to 7.5 pp in 2014) and second-generation immigrants of non-EU origin (from 4.3 pp in 2008 to 8.9 pp in 2014).

The gender ratio is reversed among people with primary level education only: this applies to a higher proportion of men than of women. Again, the biggest gender gap is among second-generation immigrants of EU origin (2.8 pp) and natives with native backgrounds (2.6 pp), while among male and female first-generation immigrants born outside the EU there is no difference. The pattern was not the same in 2008, as for some of the migration groups there was a higher proportion of women than men with primary education. This was the case for first-generation immigrants born outside of the EU (0.9 pp), second-generation immigrants with EU origins and natives (but the difference was marginal for the later two groups, 0.2 pp and -0.3 pp).

Over-qualification

In 2014, over a third of first-generation immigrants with a tertiary degree worked in a job that did not require that level of education

The previous section showed that, in general, the educational attainment of immigrants (at least as regards the proportion of tertiary graduates) is no lower than that of native-born residents with native backgrounds, but they seem in most cases to have worse employment conditions [6]. Is this because they are more likely to be over-qualified for the jobs they are in and their potential is being under-utilised? In this section, we seek to answer this question using two indicators of over-qualification: one objective (the proportion of tertiary graduates working in jobs for which a degree is not required, ISCO[7] level 4-9) and one subjective (the proportion of employed persons declaring that their qualifications and skills would allow them to carry out more demanding tasks).

Objective over-qualification by migration status and background, at EU level

In 2014, over a third of first-generation immigrants with a tertiary degree worked in a job that did not require that level of education (ranging from 34.3 % for those born in the EU to 36.2 % for those born elsewhere), as compared with around a fifth of native-born residents with native backgrounds and second-generation immigrants (Figure 5). As compared with 2008, this applied to slightly fewer first-generation immigrants born outside the EU (-1.3 pp), but significantly more EU mobile citizens (+7.2 pp). This may be related to the increased number of citizens from the countries that joined the EU most recently (Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia), who were subject to labour market restrictions in some countries until 2014. There was also an increase in the proportion of over-qualified native-born residents (+1.6 pp) and second-generation immigrants of whom both parents were born outside the EU (+1.9 pp).

Objective over-qualification by sex, migration status and background

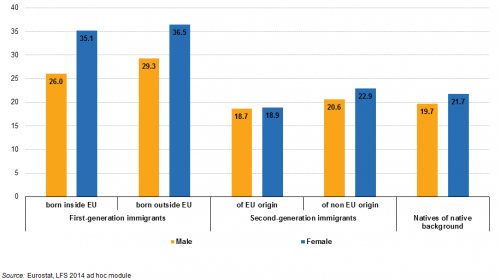

In all migration groups, female tertiary graduates are more likely than their male counterparts to accept jobs for which a tertiary degree is not required

In all migration groups, female tertiary graduates are more likely than their male counterparts to accept jobs for which a tertiary degree is not required (Figure 6). The biggest gender gap (7.5 pp) is among first-generation immigrants born outside the EU. The situation for native-born residents of EU and native origins is similar, with a gender gap of around 2 pp, while for those of non-EU origins the gap is twice as big (4.6 pp).

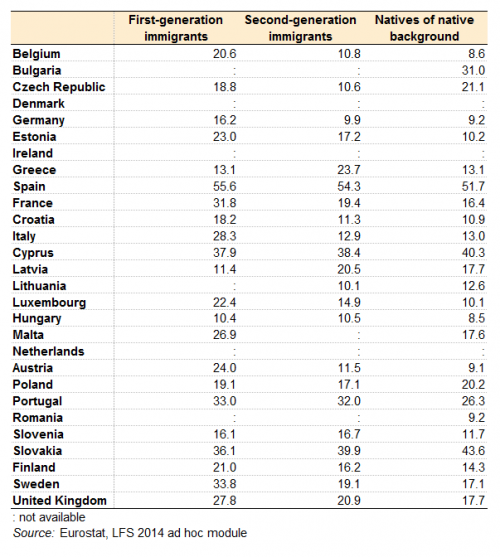

Objective over-qualification by migration status and background, by country

In Member States for which the data are available, the pattern is the same as at EU aggregated level: first generation immigrants are more likely to be over-qualified than native-born residents and second generation immigrants (Table 2). The Czech Republic and Slovenia are exceptions in this respect, as in those countries first-generation immigrants with a tertiary degree are (around 1 pp) less likely than both native-born residents with foreign and native backgrounds to be working in a medium- or low skilled job. Conversely, Italy and Greece are the countries where foreign-born residents are most likely (by 34.0 pp and 29.1 pp respectively) to be over-qualified in comparison with all native-born residents, regardless of background. The situation for second generation immigrants generally differs less from that for native-born residents with native backgrounds; in some countries (the Czech Republic, Spain, France, Austria, Slovenia, Sweden and the United Kingdom, for those with at least one parent born in an EU country), they are slightly less likely to be over-qualified, and in others (Belgium, Estonia, Greece, Italy and Cyprus) more likely.

Subjective over-qualification by migration status and background, at EU level

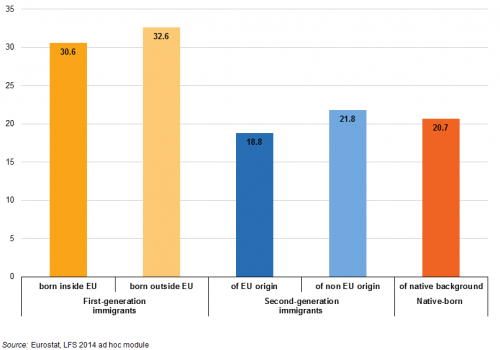

First-generation immigrants are much more likely to declare themselves as being over-qualified for their job (almost a third, as compared with around a fifth of those born in their country of residence, regardless of background)

Figure 7 shows the percentage of people in each migration group who perceived themselves as over-qualified for their main current job, based on a comparison of their qualifications and skills with the tasks they carry out. All respondents who had a job were asked about this, regardless of whether they were actually doing it in the reference week. At aggregate level, the resultant values and pattern seem to be very similar to those obtained by analysing objective over-qualification, even though the reference populations differ (all the employed population for the subjective and employed tertiary graduates for the objective measure) and the coverage is therefore not the same in all cases.

First-generation immigrants are much more likely to declare themselves as being over-qualified for their job (almost a third, as compared with around a fifth of those born in their country of residence, regardless of background). The percentage declaring themselves to be over-qualified is slightly higher among first- and second-generation immigrants of non-EU origin than among those of EU origin. Second-generation immigrants with at least one parent born in the EU are the migration group with the lowest percentage.

Subjective over qualification by sex, migration status and background

Women are much more likely than men to feel that they are over-qualified

Women are much more likely than men to feel that they are over-qualified, particularly when one looks at first generation immigrants (Figure 8). Only 26.0 to 29.3 % of male first-generation immigrants declared themselves to be over-qualified, as against 35.1 % to 36.5 % of their female counterparts. Similar, but smaller differences (2 pp) apply with native-born residents with native backgrounds and second-generation immigrants with both parents born outside the EU, while for those with an intra-EU background the percentage is similar for men and women.

Subjective over-qualification by migration status, by Member State

The proportion of employed native-born residents with native backgrounds declaring themselves to be over-qualified ranges between 10 % or less (Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, Hungary, Austria and Romania) to over 50 % (51.7 % in Spain) (Table 3). It is on the low side (below 15 %) in countries such as Estonia, Greece, Croatia, Italy, Lithuania, Slovenia and Finland, and on the high side (over 30 %) in Bulgaria, Spain, Cyprus and Slovakia. In most Member States, the proportion is lowest for native-born residents with native backgrounds, similar but slightly higher for second generation immigrants and much higher for first-generation immigrants. This is the case in Belgium, Estonia, France, Croatia, Luxembourg, Austria, Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom. In the Czech Republic, Ireland, Cyprus, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia, the proportion of those declaring themselves to be over-qualified is larger among native-born residents with native backgrounds than both migration generations. Finally, in Greece, Latvia, Hungary, the Netherlands and Slovenia the second-generation immigrants are most likely to feel over-qualified.

Language skills of first-generation immigrants

Only 10 % of immigrants in the EU declare to know the language of their country of residence at basic level or less

The information in this section refers to respondents’ self-perceived command of their host country’s main language. Where a country has more than one official language, it refers to the language of which the respondent has the best command. Around a third of first-generation immigrants move to countries in which their mother tongue is spoken, while another third (or slightly more in the case of those born in another EU country) claim to be proficient in the official language of their host country (Figure 9). Only 9% of those born in another EU country and 12% of those born in a non-EU country see themselves as having only basic knowledge of the host country’s main language.

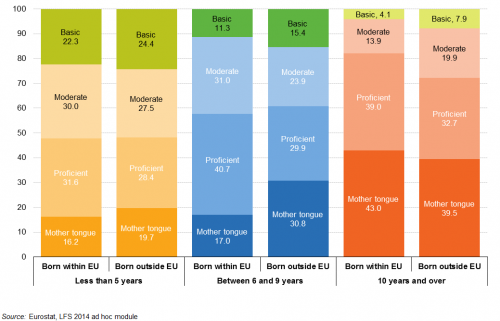

Language skills of first-generation immigrants by number of years spent in the country

First-generation immigrants’ language skills improve over time

As Figure 10 shows (and as is to be expected), first-generation immigrants’ language skills improve over time: the longer they have spent in the country, the lower the percentage declaring that they have only basic skills. However, even among people who have lived in their host country for 10 years or more, 4.1 % of those who were born in another EU country and 7.9 % of those who were born in a non EU country still said they had only basic skills in the language(s) of their host country. It is also interesting to note that the percentage of those declaring that the host country’s language is also their mother tongue is higher (about double in relative terms) among those who are settled (arrived over 10 years ago).

Language skills of first-generation immigrants by educational attainment level

On average, around 80 % of tertiary graduates are native or proficient speakers of the host country’s main language, while this applies to just over a half of foreign-born residents with primary education only

As expected, there is a correlation between better language skills and educational attainment, but it is less evident than that between better language skills and time spent in the host country (Figure 11). On average, around 80 % of tertiary graduates are native or proficient speakers of the host country’s main language, while this applies to just over a half of foreign-born residents with primary education only. The differences by migration background are insignificant.

Language skills of first-generation immigrants, by Member State

This section analyses the immigrants' perceptions of their own ability to master the (main) language of the host country. In seven of the 25 countries for which data are available (the Czech Republic, Spain, Croatia, Luxembourg, Hungary, Portugal and Slovakia), the main language of the host country is the mother tongue of at least two in five foreign-born residents (see Table 4). In another seven countries (Belgium, France, Italy, Austria, Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom), between 25 % and 40 % of all foreign-born residents regard themselves as having 'native-speaker' command of the host country's language. The proportion of native speakers among foreign-born residents is particularly high in the Czech Republic (43.7 %) and Slovakia (51.0 %), mainly because in both cases most immigrants come from the other part of the former Czechoslovakia. High proportions of foreign-born native speakers can be also attributed to the numbers coming from former dependencies (Spain, France, Portugal, the United Kingdom) or from neighbouring countries where large communities speak the language in question (Croatia, Hungary). Luxembourg is a special case due to its multilingual environment, especially as two of its national languages are widely spoken elsewhere. Other major factors are that many immigrants may have lived in the country for a long time or live in the same households as native-born residents with native backgrounds. In a few countries (Estonia, Latvia and Slovenia), only seven in every hundred foreign-born residents are native speakers. In Estonia and Malta, over half have low or no skills in the host country’s main language.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The data collected by Eurostat come from the 2014 Labour Force survey (LFS) ad-hoc module on ‘The labour market situation of immigrants and their immediate descendants’. The target population of the 2014 LFS ad-hoc module consists of all persons aged 15-64 living in private households. The EU aggregates in the article do not include data for Denmark, Ireland and the Netherlands as these countries did not participate in the 2014 LFS ad-hoc module. Germany also did not participate in the 2014 LFS ad-hoc module but thanks to our colleagues from DESTATIS, the German data are included in the article.

Context

There is high political and scientific interest in comparative information on the labour market and economic situation of immigrants. This set of comprehensive and comparable data on the situation of immigrants and their immediate descendants is aimed at monitoring progress on the situation of immigrants, to analyse the factors affecting their integration in and adaptation to the labour market and in the economy. The policy background for the 2014 ad-hoc module can be found in the following EU documents:

- The Zaragoza Declaration, adopted in April 2010 by EU Ministers responsible for immigrant integration issues, and approved at the Justice and Home Affairs Council on 3-4 June 2010. The Declaration calls upon the Commission (Eurostat and DG HOME) to carry out a pilot study to study common integration indicators from harmonised data sources.

- ‘EUROPE 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth’, outlining three mutually reinforcing objectives of smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth. It has a strong focus on employment, stressing the need for increasing labour market participation, with more and better jobs as essential elements of Europe’s socioeconomic model.

- The Commission Communication of 20 July 2011 on the ‘European Agenda for the Integration of Third Country Nationals’, which focuses on enhancing the economic, social and cultural benefits of migration in Europe and on achieving immigrants’ full participation in all aspects of collective life.

- The Commission Communication of 18 November 2011 on ‘The Global Approach to Migration and Mobility’, which sets out the Commission’s adapted policy framework on migration as part of a renewed Global Approach to Migration and Mobility (GAMM).

- The European Commission has adopted an Action Plan on the integration of third-country nationals on 7 June 2016, which provides a comprehensive framework to support Member States’ efforts in developing and strengthening their integration policies, and describes the concrete measures the Commission will implement in this regard.

Direct access to

<methodology>

Methodology / Metadata

- 2014. Migration and labour market (ESMS metadata file — lfso_14)

This article's findings base on the 2014 Labour Force Survey (LFS) ad hoc module on "The labour market situation of migrants and their immediate descendants". It focuses on first- and second-generation immigrant populations living[8] in the EU, distinguishing between those with EU and those with non-EU backgrounds [9], and comparing the four groups with each other and with native-born residents with native backgrounds. As another module on a similar topic was produced in 2008, we also make comparisons with that reference year where possible.

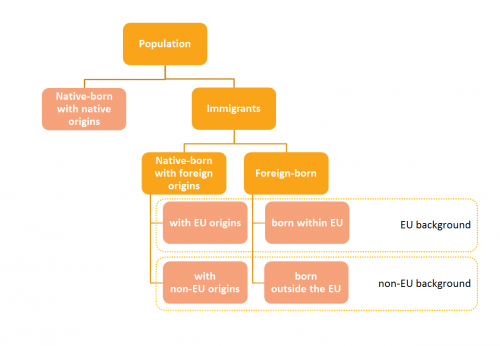

The population is divided into three main ‘migration status’ categories, on the basis of the country of birth of the respondent and of their parents:

- first-generation immigrants (foreign-born [10] population);

- second-generation immigrants (native-born population with at least one foreign-born parent); and

- native-born residents with native backgrounds.

This article looks at the differences between these categories and at their migration background. For example, it highlights differences between people with an EU and a non-EU migration background and compares them with people with no migration background. In this context, ‘native origin’ means that the country of birth of the respondent and of her/his parents is the reporting country, while ‘EU background’ means that the country of birth of the respondent or of her/his parents is an EU country other than the reporting country.

The migration background of a native-born adult is based on the country of birth of her/his parents. Thus, if neither parent is foreign-born, the native-born adult has native origins. However, if at least one parent is foreign-born, the native-born adult is considered to have an EU background if at least one parent was born in the EU (including in the reporting country) and a non-EU background if both parents were born outside the EU. The migration background of a foreign-born adult is based on his/her country of birth: EU background if this is in the EU and non-EU background if it is not.

The analysis covers five immigrant populations (see Figure 1):

- first-generation immigrants born in another Member State [11];

- first-generation immigrants born outside the EU;

- second-generation immigrants of EU origin (native-born with at least one foreign parent where at least one parent was born in an EU country, including the reporting one);

- second-generation immigrants of non-EU origin (native-born with both parents born outside the EU); and

- native-born residents with native backgrounds (i.e. both parents are also native-born).

In principle, the analysis covers the whole working age population (aged 15 to 64), but some parts focus on the 25 54 age group, in order to reduce the effect of different age structures in the three main migration status groups.

- COM (2004) 811 Green Paper on an EU approach to managing economic migration

- COM (2005) 669 Communication from the Commission — Policy Plan on Legal Migration

- Summaries of EU Legislation: Policy plan on legal migration

- COM (2006) 402 Communication from the Commission on Policy priorities in the fight against illegal immigration of third-country nationals

- Summaries of EU Legislation: Policy priorities in the fight against illegal immigration

- COM (2007) 512 Communication from the Commission — Third Annual Report on Migration and Integration

- COM (2008) 611 Communication from the Commission — Strengthening the global approach to migration: increasing coordination, coherence and synergies

- Summaries of EU Legislation: Strengthening the Global Approach to Migration

- COM (2010) 171 Communication from the Commission — Delivering an area of freedom, security and justice for Europe's citizens — Action Plan Implementing the Stockholm Programme

- Summaries of EU Legislation: Action plan on the Stockholm Programme

- Regional Statistics Illustrated - select statistical domain 'Population' 'and 'Demography' (top right)

<notes>

Notes

- ↑ EU mobile citizens’ are people born in the EU who live in a Member State other than that in which they were born, as a result of the free movement, a right linked to EU citizenship. Therefore, the terms ‘first-generation immigrant born in the EU’ and ‘EU mobile citizen’ are used interchangeably in this article

- ↑ According to the "International Standard Classification of Education" (ISCED11),

- ↑ As tertiary graduates represent a relatively small proportion of the population and first- and second-generation immigrants are not a significant minority in many EU countries, the breakdown by migration background often produces data that are not reliable at national level. Therefore, the migration background dimension is removed for all analysis at country level.

- ↑ The article looks at the following three age groups:

- young workers (from 15 to 24 years);

- core working-age group (from 25 to 54 years); and

- older workers (from 54 to 64 years).

- ↑ See Statistics Explained article on First- and second-generation immigrants - statistics on main characteristics (a hyperlink will be added once the article is visible for all users)

- ↑ See Statistics Explained article on First- and second-generation immigrants - statistics on labour market indicators

- ↑ International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO).

- ↑ The LFS covers the resident population. The concept of ‘usual residence’ is used to define an immigrant. The terms ‘to live’ and ‘to reside’ are used interchangeably in this article.

- ↑ The term ‘background’ refers here to the total of a person’s experience, knowledge and education (see Merriam-Webster dictionary). ‘Migration background’ thus refers to a person’s origins as the main determinant of his/her experience, knowledge and education. ‘Background’ and ‘origins’ are therefore synonymous in the context of this article.

- ↑ A foreign-born person is a person born in a country other than the country of residence. The terms ‘first-generation immigrant’ and ‘foreign-born resident’ are used interchangeably in this article.

- ↑ ‘EU mobile citizens’ are people born in the EU who live in a Member State other than that in which they were born, as a result of the free movement, a right linked to EU citizenship. Therefore, the terms ‘first-generation immigrant born in the EU’ and ‘EU mobile citizen’ are used interchangeably in this article.