Archive:Being young in Europe today - living conditions for children

Data extracted in July 2020.

Planned article update: November 2022.

Highlights

Children aged less than 18 years accounted for almost one fifth of the total number of persons in the EU-27 at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2018.

Some 10.8 % of households in the EU-27 with dependent children faced the risk of in-work poverty in 2018, a share that was 2.9 percentage points higher than that recorded for households without dependent children.

In 2018, severe material deprivation affected 22.7 % of children in the EU-27 whose parents had at most a lower secondary level of education, compared with 6.9 % for those children whose parents had an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary level of education and 1.4 % for those children whose parents had a tertiary level of education.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pees01)

This is one of a set of statistical articles that forms Eurostat’s flagship publication Being young in Europe today. It presents a range of statistics covering children’s (aged 0-17) living conditions in the European Union (EU), the vast majority of the data is derived from EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), a wide-ranging source of information about living conditions in general and about poverty and social exclusion in particular.

This article provides: information relating to the risk of monetary poverty among children; details concerning the ease with which families with/without children can afford a range of goods; information on the housing conditions in which children live; as well as evidence linking a child’s risk of poverty and deprivation to their parents’ labour market situation and educational attainment.

It is widely accepted that children benefit from growing up in households with sufficient resources to meet their essential needs, while their future well-being is enhanced through ensuring they have access to a range of services and opportunities including, among others, early childhood education and recreational, sporting and cultural activities. Most EU Member States have a range of policies that aim to tackle child poverty. These tend to be based around promoting children’s rights, although there are differences in the balance struck between promoting universal measures and targeting support at specific (vulnerable) groups [1].

Full article

Poverty and social exclusion

Just under one quarter of all children in the EU-27 were at risk of poverty or social exclusion

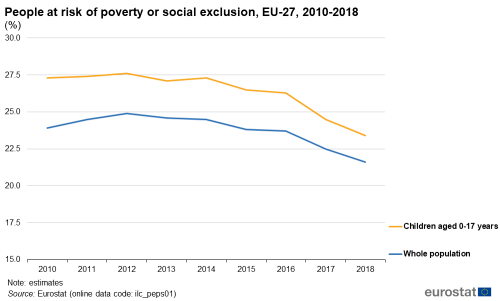

Figure 1 shows the proportion of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU-27 since 2010, with information presented for children aged 0-17 years and for the whole population. The aftermath of the global financial and economic crisis (and subsequent sovereign debt crisis) was apparent with both shares continuing to rise up until 2012. In 2012, more than one quarter (27.6 %) of children living in the EU-27 were living at risk of poverty or social exclusion. From this recent high point, the share of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion was largely unchanged up until 2014, after which it fell during consecutive years to 23.4 % in 2018. For comparison, some 24.9 % of the total EU-27 population was at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2012, with this share falling to 21.6 % by 2018.

It is interesting to note that the gap between the share of children and the share of the total population that was at risk of poverty or social exclusion narrowed when comparing the situation for 2018 with that for 2010. This gap — with a higher risk of poverty or social exclusion among children — had been 3.4 percentage points in 2010. Aside from an increase in 2014, the gap declined each year through to 2018 when it stood at 1.8 points.

Children accounted for more than one in five of those at risk of poverty or social exclusion

In absolute numbers, a total of 94.7 million persons in the EU-27 were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2018; this figure included 18.9 million children. As such, children accounted for one fifth (19.9 %) of the total number of persons in the EU-27 at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2018.

Households with children are usually financially worse off when compared with households without children, as the former face more expenditure linked to the cost of bringing up children. Indeed, from a statistical perspective the number of children in a family directly influences the risk of monetary poverty, as each extra child in a family increases the family size and so reduces average income per family member. Governments may choose to target specific types of family units through social transfers and allowances (for example, child allowance or tax credits), often with the goal of encouraging people to have (more) children. These transfers may balance, to some degree, the income situations of families with and without children, with social benefits and taxation likely to mitigate some of the differences.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_peps01)

Three conditions which concern the risk of poverty and social exclusion

The headline indicator covering the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion is defined as the share of the population in at least one of the following three conditions: i) at risk of poverty, which means living below the poverty threshold, ii) in a situation of severe material deprivation, iii) living in a household with very low work intensity.

DEFINING POVERTY AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION

Persons at risk of poverty are those living in households with an equivalised disposable income below a certain threshold. The risk of poverty is a relative measure, which is conventionally set against a threshold of 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income (after social transfers) — this means the poverty threshold varies between countries, as well as over time.

Severe material deprivation concerns persons whose living conditions are constrained by a lack of resources and experience of at least four out of nine deprivation items. The deprivation items concern the inability to be able to afford: i) to pay rent/mortgage or utility bills on time, ii) to keep their home adequately warm, iii) to face unexpected expenses, iv) to eat meat, fish or a protein equivalent every second day, v) a one week holiday away from home, vi) a car, vii) a washing machine, viii) a colour television, or ix) a telephone (including mobile telephones).

People living in households with very low work intensity are those aged 0-59 years who live in households where the adults aged 18-59 years worked, on average, less than 20 % of their total work potential during the previous year; students are excluded.

Household income is equivalised (or adjusted) so that the incomes of different types of households can be compared, based on the premise that household income is shared and that there are some economies of scale which result from living together. To do so, total household disposable income is divided by the household’s size. To calculate the size, Eurostat uses the ‘modified OECD equivalence scale’ which first gives a weight of 1.0 to the first adult, 0.5 to any other household member aged 14 years and over, and 0.3 to each child aged 0-13 years and then the sums the weights within each household. The resulting average income figure is allocated to each member of the household, regardless of whether they are an adult or a child.

It is sometimes said that it is impossible to abolish poverty as the relative poverty line is always moving, and as income increases so too does the poverty line. However, it is possible for incomes to increase without affecting the median level of income: for example, a tax break for high wage earners would increase their disposable income without changing the median, while the introduction of a new social transfer targeted specifically at poorer people could result in some households being pulled above the poverty threshold without a change in the median level of income.

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pees01)

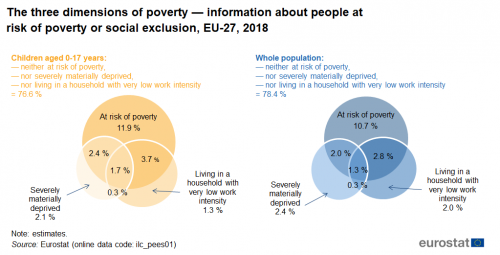

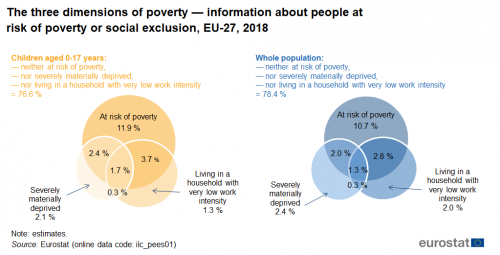

Figure 2 shows how these three conditions that make up poverty and social exclusion can overlap — note that a person can experience none, one, two or all three of these poverty and/or social exclusion conditions. Outside of the three circles shown in Figure 2, more than three quarters (76.6 %) of the children in the EU-27 did not experience any form of poverty or social exclusion in 2018, while the corresponding share for the whole population was slightly higher, at 78.4 %.

Among the 18.9 million children in the EU-27 who were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2018, some 6.5 million were simultaneously affected by more than one of these three conditions. Of these, 1.9 million children were at risk of poverty and severe material deprivation, 3.0 million were at risk of poverty and living in a household with very low work intensity, 0.3 million were both materially deprived and living in a household with very low work intensity, while 1.4 million were touched by all three conditions (in other words, those simultaneously at risk of poverty, in a situation of severe material deprivation and living in a household with very low work intensity). As such, the proportion of children in the EU-27 that were experiencing all three poverty and social exclusion conditions was 1.7 % in 2018 — again this was higher than the corresponding proportion for the whole population (1.3 %).

Monetary poverty was the risk that most affected children

Figure 3 shows developments over time for the proportion of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion; it provides information about the three conditions described above. From looking at the headline indicator, it is clear that monetary poverty — the proportion of children at risk of poverty (but not severely materially deprived and not living in a household with very low work intensity) — was the most widespread form of poverty or social exclusion among children, affecting between 10.9 % and 12.0 % of all children in the EU-27 during the period 2010-2018. The proportion of EU-27 children affected by any form of monetary poverty (in other words, on its own or in combination with one or both of the other conditions) stood at just less than one fifth (19.6 %) in 2018; this was higher than the proportion of the whole EU-27 population (children and adults) that was affected by any form of monetary poverty (16.8 %).

Between 2010 and 2015, the number of children in the EU-27 experiencing all three poverty and social exclusion conditions simultaneously increased by about 320 thousand. This was due, at least in part, to the effects of the global financial and economic crisis. Thereafter, the number of children in the EU-27 who were at risk of all three conditions fell at a relatively rapid pace, down by almost 880 thousand (or almost 40 %) between 2015 and 2018.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pees01)

The proportion of children suffering from severe material deprivation rose rapidly in 2012 then decreased …

Prior to the global financial and economic crisis, the proportion of children in the EU-27 that were exclusively facing severe material deprivation or living in households with very low work intensity fell. This occurred as the EU economy grew, disposable incomes and employment levels tended to rise, and with more people in work, households had — on average — more money to purchase goods and services. With the onset of the crisis, there was a subsequent increase in the proportion of children that were living in households with very low work intensity (exclusively or in combination with other conditions); this reflected at least in part increasing unemployment levels and weak demand for labour. The share of children suffering from material deprivation (exclusively or in combination with other conditions) rose at a modest pace in 2011 and more rapidly in 2012. During the period 2012-2018, the proportion of children in the EU-27 who were materially deprived decreased and returned to a level that was below that recorded at the onset of the crisis.

… while the share of children at risk of monetary poverty rose at the onset of the global financial and economic crisis and — despite abating during the period 2009-2012 —continued to rise thereafter

During a period of economic expansion in the EU (2005-2008), the share of children that were exclusively at risk of poverty (but not facing severe material deprivation or living in a household with very low work intensity) rose. While this may seem a contradictory result, it may be explained through an increasing degree of inequality in relation to the distribution of incomes. Although those at the lower end of the income scale saw their living standards rise during the period 2005-2008, the rate at which their incomes rose was slower than the rate for the whole population, and as such a higher proportion of households and children fell into relative poverty. Following the onset of the global financial and economic crisis, the proportion of children that were exclusively at risk of monetary poverty started to fall — a pattern that continued through to 2013. With a gradual upturn in economic fortunes across the EU-27, the share of children exclusively at risk of monetary poverty once again started to increase, rising from a relative low of 10.9 % in 2013 to 12.0 % in 2016, after which it declined slightly (and reached 11.9 % in 2018).

Among EU Member States where the overall risk of poverty was high the risk of poverty among children also tended to be high

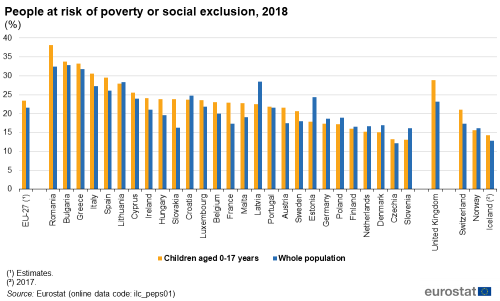

As already shown, children in the EU-27 were at a greater risk of poverty or social exclusion (23.4 %) in 2018 than the population as a whole (21.6 %). Figure 4 shows that a similar pattern existed across the majority of the EU Member States, with the gap between the two rates particularly high in Slovakia, Romania and France, where the risk of poverty or social exclusion for children was more than 5.0 percentage points above the average for their populations as a whole. By contrast, there were 10 Member States where a lower proportion of children were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Although the gap was relatively modest in most of these Member States (less than 2.0 points difference), it stood at 3.1 points in Slovenia, 5.9 points in Latvia and peaked at 6.5 points in Estonia.

In Romania, Bulgaria and Greece, at least one third of all children were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2018, while relatively high rates — within the range of one quarter to one third of all children were at risk in Italy, Spain, Lithuania and Cyprus. By contrast, the proportion of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion was much lower — at most 16.0 % — in Finland, the Netherlands, Denmark, Czechia and Slovenia.

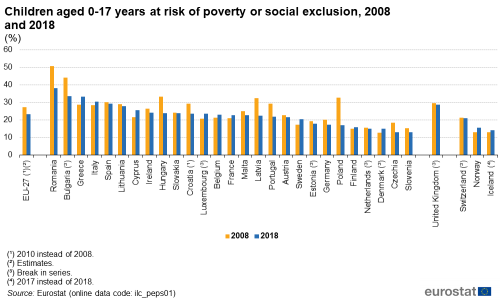

Figure 5 shows a comparison between 2008 and 2018 for the proportion of children in the EU-27 at risk of poverty or social exclusion; note that this comparison over the last decade conceals considerable variations among the EU Member States, especially in relation to the impact of the global financial and economic crisis. Between the two reference periods shown, the share of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion fell by 3.9 percentage points across the whole of the EU-27 (2010-2018). The Member States that displayed the greatest decrease in their share of vulnerable children in society between 2008 and 2018 included Poland, Romania and Bulgaria (note that there is a break in series); all three of these recorded a double-digit reduction in the share of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion. The next largest decreases were recorded in Latvia (down 9.9 points), Hungary (down 9.6 points) and Portugal (down 7.6 points). An additional 12 Member States recorded a fall in their share of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion between 2008 and 2018.

The proportion of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion was particularly high among some of the EU Member States that were most deeply affected by the global financial and economic crisis

By contrast, some of the EU Member States where the proportion of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion rose at its most rapid pace between 2008 and 2018 were characterised as having been deeply affected by the global financial and economic crisis, for example Greece, Cyprus and Italy. Alongside a contraction in economic activity, these Member States were also characterised by austerity policies, which may have impacted upon some measures and services designed to support children. The proportion of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion also rose in the three Nordic Member States and three western Member States — Luxembourg, Belgium and France; note that there are breaks in series in Denmark and Luxembourg.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_peps01)

What impact does a parent’s education and job have on a child’s risk of poverty?

It can be argued that the opportunities afforded to children as they grow up should not be determined by the characteristics of the family into which they were born. That said, each child is born with a unique set of genes that may, at least in part, make them prone to certain abilities or levels of health. Furthermore, parents can influence the life outcomes for their children, through nurturing, encouraging aspirations, and investing time and money in their education and health, while external social, cultural and economic environments may also play a role in shaping a child’s development. These determinants define a child’s life chances as they mature into adults and participate in life in one or more other ways, such as looking for work or establishing their own household.

More than 1 in 10 households with dependent children were affected by in-work poverty

There is an old saying that work is the surest way to get out of poverty. However, in recent years there has been a sharp rise in precarious [2], such as short-term contracts, low-pay or part-time work. Low wage growth, households where only one adult is in employment and households where those in work only have limited contracts are some of the reasons why an increasing share of working families remain at risk of poverty. Furthermore, it is likely that some parents work a limited number of hours each week in order to balance their professional and private lives; while for some this may be a lifestyle choice, the proportion of people that do so may, at least in part, be linked to the availability of adequate childcare arrangements for working parents [3].

In-work poverty is defined as the proportion of persons who are at work and have an equivalised disposable income below the risk of poverty threshold, which is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income (after social transfers). Some 10.8 % of households in the EU-27 with dependent children faced the risk of in-work poverty in 2018, a share that was 2.9 percentage points higher than that recorded among households without dependent children (see Figure 6). Romania (17.4 %) recorded the highest rate of in-work poverty for households with dependent children, followed by Spain (15.8 %) and Italy (15.5 %).

The in-work at risk of poverty rate was higher among households with dependent children (compared with those without children) in the majority (23) of EU Member States. In 2018, the biggest difference was recorded in Bulgaria (where the in-work at risk of poverty rate was 6.9 percentage points higher among households with dependent children). There were also relatively large differences — more than 5.0 points — in Italy, Spain, Slovakia, Greece and Malta. By contrast, the in-work at risk of poverty rate was lower among households with dependent children (than among households without dependent children) in four Member States in 2018: Denmark, Sweden, Slovenia and Cyprus.

PARENTAL EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

Intergenerational poverty may be viewed in relation to the educational attainment of a child’s parents. The international standard classification of education (ISCED 2011) covers nine levels of education:

- ISCED level 0 — early childhood education;

- ISCED level 1 — primary education;

- ISCED level 2 — lower secondary education;

- ISCED level 3 — upper secondary education;

- ISCED level 4 — post-secondary non-tertiary education;

- ISCED level 5 — short cycle tertiary education;

- ISCED level 6 — Bachelor’s or equivalent level;

- ISCED level 7 — Master’s or equivalent level;

- ISCED level 8 — Doctoral or equivalent level.

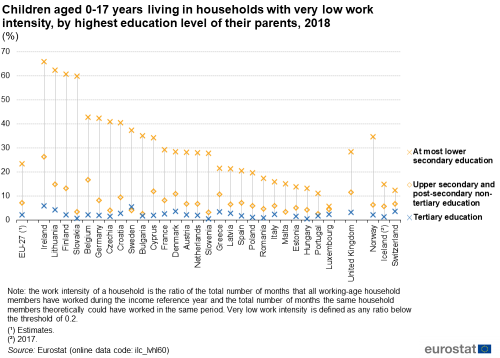

Almost one out of four children whose parents had no more than a lower secondary level of education lived in households characterised by very low work intensity

Figure 7 extends the information by looking at the share of children who live in households with very low work intensity presented for each EU Member State by the highest level of education attained by either parent. Almost one quarter (23.4 %) of all children in the EU-27 whose parents had at most a lower secondary level of education (ISCED levels 0-2) lived in a household with very low work intensity in 2018. The share living in households with very low work intensity was considerably lower among those children whose parents remained longer in the education system, standing at 7.1 % for children whose parents had an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary level of education (ISCED levels 3 and 4), and 2.1 % for children whose parents had a tertiary level of education (ISCED levels 5-8).

This pattern was repeated in all but one of the EU Member States in 2018; the exception was Sweden, where a higher proportion of children whose parents had a tertiary level of education were living in households with very low work intensity when compared with children whose parents had no more than an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (5.3 % compared with 3.9 %).

Among children whose parents had no more than a lower secondary level of education, almost two thirds (65.9 %) of the children in Ireland found themselves living in a household with very low work intensity in 2018, a share that, by comparison, was less than 15.0 % in Malta, Estonia, Hungary and Portugal, and Luxembourg (where it was 5.7 %). By contrast, the proportion of children whose parents had completed a tertiary level of education and who found themselves living in households with very low work intensity was considerably lower, ranging between a high of 5.8 % in Ireland and a low of just 0.4 % in Hungary and Slovenia (while Slovakia and Romania also reported shares below 1.0 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvhl60)

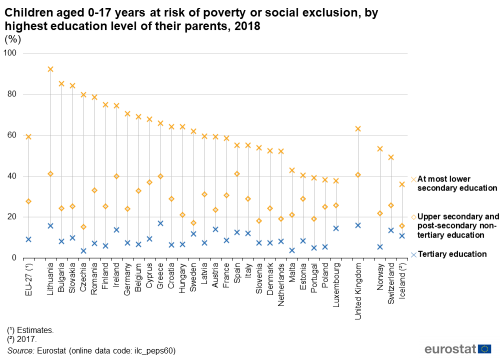

Children whose parents had a higher level of education were, on average, exposed to a lower risk of poverty or social exclusion

Almost three fifths (59.3 %) of all children in the EU-27 whose parents had attained no more than a lower secondary level of education were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2018 (see Figure 8). This group of children were more than twice as likely to face the risk of poverty or social exclusion as children whose parents had an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (27.6 %). The risk of poverty or social exclusion was considerably lower among children whose parents had a tertiary level of education (9.0 %).

This pattern was repeated in each of the EU Member States with the risk of poverty or social exclusion for children consistently highest among children born to parents with at most a lower secondary level of educational attainment. Even in the Member States where the differences were at their smallest — Luxembourg, Estonia, Poland, Portugal and Malta — children whose parents had at most a lower secondary level of educational attainment were 23-39 percentage points more likely to be at risk of poverty or social exclusion than children whose parents had a tertiary level of educational attainment. The level of parental educational attainment had a far greater impact on a child’s risk of poverty or exclusion in Bulgaria, Lithuania, Czechia, Slovakia and Romania, as children whose parents had at most a lower secondary level of educational attainment had a risk of poverty or social exclusion that was 70-77 points higher.

Children of wealthier and more educated parents appear to have a higher chance of succeeding at school, better health [4], and (upon starting work) earn higher incomes, while the converse is true among those born into poorer families [5]. This section has shown that both in-work poverty and parental educational attainment may be closely linked to the risk of poverty or social exclusion, supporting the notion of intergenerational transmission of poverty (in other words, a cycle of poverty being passed from one generation to the next).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_peps60)

Material deprivation of children: the inability to afford a range of goods and services

The majority of the information presented in this article so far has been focused on relative measures of poverty, referring to national poverty thresholds. Material deprivation is an absolute measure of poverty and provides a useful complement when looking at poverty and social exclusion; for a definition of material deprivation and severe material deprivation, see the box titled ‘Defining poverty and social exclusion’. The indicators included in this section are defined in relation to the enforced inability to afford a range of goods and services, considered to be desirable or even necessary to lead an adequate life. A number of examples are presented, starting with the proportion of households that are in arrears on regular payments, before moving on to the (in)ability of households to afford a computer or a range of goods and services that cater for the specific needs of children.

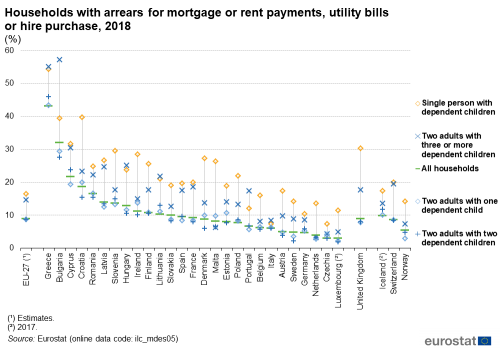

A higher proportion of households with children were in arrears for regular payments

Figure 9 provides information by EU Member State in relation to the proportion of households that faced arrears in paying their mortgage or rent, utility bills or hire purchase items; in other words, people who could not keep up with the regular payments that most households face as part of their monthly budget. The information presented shows that, on average, single adult households with dependent children and households with two adults and three or more dependent children were more likely to face difficulties in making these regular payments than was typical for all households.

Some 8.9 % of all households in the EU-27 had arrears (for mortgage or rental payments, utility bills or hire purchase payments) in 2018. This figure reached approximately one in six (16.5 %) among households composed of a single adult with dependent children, while households composed of two adults and dependent children generally were less likely to face difficulties in making regular monthly payments. This was most notably the case for two adult households with a single child or with two dependent children, as both of these types of household recorded rates of 8.7 %, which was slightly lower than the rate for all households in the EU-27. Households with two adults and a higher number of dependent children — three or more — were more likely to face difficulties to make regular payments (14.6 %).

Among the EU Member States, more than half of all households composed of a single adult with dependent children in Greece (54.3 %) and 30-40 % of households composed of a single adult with dependent children in Croatia, Bulgaria and Cyprus had arrears in 2018. The proportion of households composed of a single adult with dependent children in arrears was consistently higher than the proportion for all households in each of the EU Member States. In five Member States, namely Croatia, Denmark, Malta, Ireland and Slovenia, the proportion of single person households with dependent children that faced arrears was more than 15 percentage points higher than the proportion for all households; the largest gap was recorded in Croatia (21.1 points).

Some 14.6 % of households composed of two adults with three or more dependent children in the EU-27 faced arrears in 2018. This share stood at more than half (57.2 % and 55.0 %) of such households in Bulgaria and Greece, while it was 30.4 % in Cyprus and 25.1 % in Hungary. By contrast, less than 1 in 20 households composed of two adults and three or more dependent children in the Netherlands (3.3 %), Czechia (4.3 %) and Luxembourg (4.9 %; 2017 data) faced arrears.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdes05)

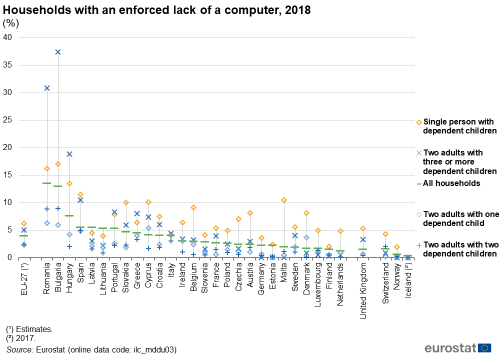

Single person households with dependent children were more likely to be unable to afford a computer

Just less than 1 in 25 (3.9 %) households across the EU-27 faced difficulties in being able to afford a computer in 2018. Among households where a single person was living with dependent children, this proportion reached 6.2 %. By contrast, households composed of two adults with dependent children were less likely to be un able to afford a computer (see Figure 10).

Among the EU Member States, the highest shares of households that were unable to afford a computer were located in Bulgaria and Romania and composed of two adults with three or more dependent children. More than one third (37.4 %) of these households in Bulgaria faced an enforced (for financial reasons) lack of a computer in 2018, while in Romania the equivalent share was 30.8 %; Hungary (18.8 %) and Spain (10.5 %) were the only other Member States to record double-digit shares for this type of household. In Bulgaria, the proportion of households composed of two adults with three or more dependent children that were unable to afford a computer was 24.5 percentage points higher than the proportion for all households in 2018, while the difference was 17.3 points in Romania and 11.2 points in Hungary; none of the remaining EU Member States recorded a double-digit gap. By contrast, in 12 of the Member States the proportion of households composed of two adults with three or more dependent children that faced difficulties in being able to afford a computer was lower than the proportion for all households. This situation was most notable in the Baltic Member States and Germany, as the shares for their households composed of two adults with three or more dependent children were 2.1-3.1 points lower than their respective shares for all households.

The share of single person households with dependent children that faced difficulties in being able to afford a computer in 2018 stood at 17.0 % in Bulgaria, 16.2 % in Romania and was at least 10.0 % in Hungary, Spain, Malta, Cyprus and Slovakia. By contrast, Lithuania and Latvia were the only EU Member States where single person households with dependent children were less likely to be unable to afford a computer than was the case for all households. The proportion of households composed of a single adult with dependent children facing difficulties in being able to afford a computer was 1.4 points lower than the proportion for all households in Lithuania and was 1.0 points lower in Latvia.

Households composed of two adults and no more than two dependent children were generally less likely to be unable to afford a computer than was the case for all households. The proportion of households with two adults and a single child or two dependent children that faced difficulties in being able to afford a computer was generally lower than 5.0 %. In 2018, the only exceptions for households with two adults and two dependent children were Bulgaria (8.9 %) and Romania (8.8 %), while the only exceptions for households with two adults and one dependent child were Romania (6.3 %), Bulgaria (5.9 %) and Cyprus (5.4 %).

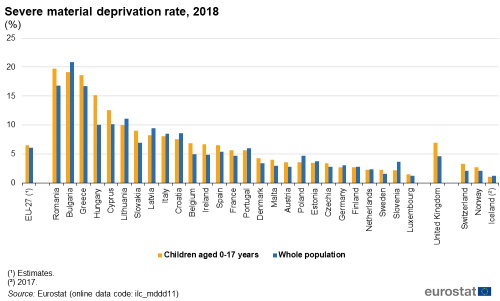

Severe material deprivation rates were slightly higher for children (than for the whole population)

In 2018, the proportion of children in the EU-27 experiencing severe material deprivation was slightly higher than the corresponding ratio for the whole population (6.5 % compared with 6.1 %; see Figure 11). The share of children experiencing severe material deprivation was higher than the share for the whole population in 15 of the EU Member States. Hungary (5.1 percentage points) was the only Member State where the proportion of children experiencing severe material deprivation in 2018 was more than 3.0 points above the proportion for the whole population. Across the 12 Member States where a lower proportion of children (than of the whole population) faced severe material deprivation in 2018, the difference between these two proportions was generally no more than a single percentage point, although slightly larger gaps were recorded in Bulgaria, Slovenia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Severe material deprivation among children inversely related to parental educational attainment

Across the EU-27, severe material deprivation in 2018 affected more than one fifth (22.7 %) of children whose parents had attained no more than a lower secondary level of educational attainment (see Figure 12). The proportion was considerably lower among children whose parents had attained an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary level of education (6.9 %) or a tertiary level of education (1.4 %).

In 2018, the share of children whose parents had a tertiary level of educational attainment that experienced severe material deprivation was less than 0.5 % in Slovenia, Hungary, Czechia, Finland and Austria. By contrast, more than half of all children whose parents had no more than a lower secondary level of educational attainment in Bulgaria, Lithuania, Slovakia and Hungary faced severe material deprivation.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddd60)

Housing quality and satisfaction

The cost and quality of housing are key elements that contribute to overall living standards and well-being. Indeed, the risk of poverty is strongly linked to the burden of sustaining a household and is therefore especially difficult for people with relatively low incomes. As such, indicators that measure the quality, facilities and space available within dwellings may provide complementary information for assessing the material conditions of different groups within society. Housing quality can be assessed by looking at a range of housing deficiencies, such as a lack of sanitary facilities (a bath or shower, or indoor flushing toilet) and problems relating to the general condition of a dwelling (a leaking roof, or a dwelling that is considered to be too dark). Note that the statistics presented in this section refer to questions that were asked only once for all members of each household surveyed.

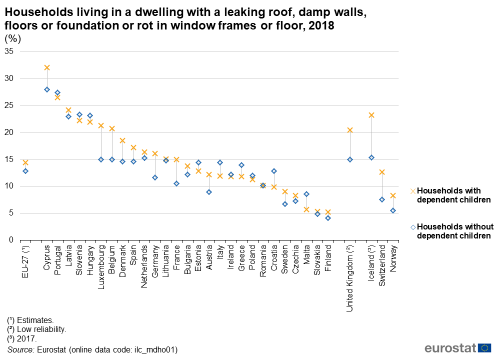

The vast majority of people in the EU-27 did not face any difficulties concerning the quality of their housing. In 2018, some 14.4 % of households with dependent children were living in a dwelling with a leaking roof, damp walls, floors or foundation or rot in window frames or floor. This was 1.6 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for households without dependent children (12.8 %; see Figure 13). Among the EU Member States, almost one third (32.0 %) of Cypriot households with dependent children faced difficulties concerning the quality of their dwelling, while this was also the case for more than one quarter of households with dependent children in Portugal, and for more than one fifth of households with dependent children in Latvia, Slovenia, Hungary, Luxembourg and Belgium.

In 2018, the share of households with dependent children that were living in a dwelling with a leaking roof, damp walls, floors or foundation or rot in window frames or floor was higher than the corresponding share for households without dependent children in 16 of the EU Member States; there was no difference between these two shares in Romania. The biggest difference was recorded in Luxembourg, as the share of households with dependent children that faced such difficulties was 6.3 percentage points higher than the share among households without dependent children. A similar pattern was observed in Belgium, Germany, France and Cyprus, where the share of households with dependent children that faced such difficulties was 4.1-5.8 points higher than the share among households without dependent children.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdho01)

HOUSING

One dimension for assessing the quality of housing conditions is the availability of sufficient space in a dwelling. The overcrowding rate describes the proportion of people living in an overcrowded dwelling, as defined by the number of rooms available to the household, the household’s size, as well as its members’ ages and their family situation.

The severe housing deprivation rate is defined as the share of the population living in dwellings which are considered as being overcrowded, while at the same time having at least one of the following housing deprivation measures: no bath/shower and no indoor toilet; a leaking roof; or a dwelling considered too dark.

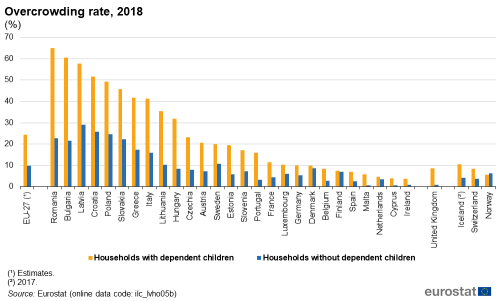

Almost one quarter of all households with dependent children suffered from overcrowding

To some degree, the indicator presented above may be considered as subjective, insofar as it is based upon the perception of each respondent. Data on housing quality and satisfaction can be extended and balanced by referring to a range of objective indicators. Indeed, EU-SILC provides a measure of overcrowding that is based on the number of rooms and the number of people living in a household. In 2018, the EU-27 overcrowding rate [6] for households with dependent children was 24.4 %, which was 14.7 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for households without dependent children (9.7 %).

Among EU Member States, the highest rates of overcrowding for households with dependent children were observed in Romania (65.1 %), Bulgaria (60.6 %), Latvia (57.8 %) and Croatia (51.7 %); these were the only EU Member States to report that more than half of their households with dependent children were overcrowded. There were eight EU Member States in 2018 with overcrowding rates for households with dependent children that were less than 10.0 %; the lowest shares (less than 5.0 %) were recorded in the Netherlands, Cyprus and Ireland. The overcrowding rate for households with dependent children was consistently higher than the rate for households without dependent children in each of the Member States (see Figure 14).

In 2018, the overcrowding rate for EU-27 households with dependent children was 2.5 times as high as the rate for households without dependent children. In a majority (19) of the EU Member States the overcrowding rate for households with dependent children was at least twice as high as the rate for households without dependent children. The overcrowding rate for households with dependent children was five times as high as the rate for households without dependent children in Portugal, rising to 5.7 times as high in Cyprus and 8.4 times as high in Malta.

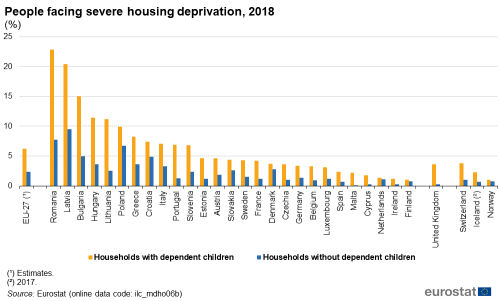

Severe housing deprivation is defined in relation to insufficient space and poor amenities [7]. In 2018, the severe housing deprivation rate for households with dependent children in the EU-27 was 6.2 %, which was 2.6 times as high as the corresponding rate for households without dependent children (2.4 %).

In 2018, the highest severe housing deprivation rates among households with dependent children were exhibited in Romania (22.8 %) and Latvia (20.4 %); none of the remaining EU Member States recorded severe housing deprivation rates for households with dependent children that were above 15.0 %. By contrast, severe housing deprivation rates were within the range of 1.0-2.0 % for households with dependent children in Cyprus, the Netherlands, Ireland and Finland.

A comparison between severe housing deprivation rates for people living in households with and without dependent children in 2018 reveals that the former were consistently more likely to be affected by severe housing deprivation, across all EU Member States. This was most notably the case in Romania, Latvia and Bulgaria, where people living in households with dependent children recorded severe housing deprivation rates that were at least 10.0 percentage points higher than those for people living in households without dependent children. In Malta, Cyprus, Portugal, Lithuania and Ireland, people living in households with dependent children were at least four times as likely as people living in households without dependent children to face severe housing deprivation (see Figure 15).

Conclusions: what does the future hold for child poverty and social exclusion in the EU?

Children that grow up in poverty are more likely to suffer from social exclusion and other negative outcomes in life, while they are also less likely to develop to their full potential. Breaking this cycle of disadvantage in a child’s early years can potentially reduce the risk of poverty or social exclusion.

Although tackling poverty and social exclusion can lead to benefits not only for the individuals concerned but also for society at large, the economic climate during and after the global financial and economic crisis did little to help policymakers face these widespread challenges. Furthermore, in recent years there have been signs that the (re-)distribution of income is becoming increasingly unequal in the EU while real incomes (for some people) have stagnated or even fallen in a number of EU Member States that were particularly affected by the crisis and/or the subsequent sovereign debt crisis. This has resulted in an increasing share of the EU’s population suffering from a lack of work, monetary poverty and/or social exclusion and material deprivation. The impact of the crisis was proportionally greater for households with children than for those without.

This article has shown that the risk of poverty is more common among children than it is for the population as a whole. This is particularly the case when children live in households that are characterised by the presence of a single adult or a low degree of work, while parental educational attainment also appears to have a marked impact upon the risk of poverty or social exclusion experienced by children.

Source data for table and graphs

Data sources

The data used in this article are primarily derived from EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), established under Regulation (EC) No 1177/2003. EU-SILC is a multi-purpose instrument that focuses mainly on income, but also gathers information on social inclusion/exclusion, material deprivation, housing conditions, labour market participation, education and health. It is carried out annually and has a reference population of all private households and their current members residing in the territory of EU Member States; persons living in collective households and in institutions are generally excluded from the target population. The EU-27 aggregate is a population-weighted average of national data. Children are defined as persons aged 0-17 years.

Context

GIVING CHILDREN A LIFE CHANCE

The risk of poverty among children appears to be closely linked to the composition of the household into which they are born, in particular, the labour market situation, marital status and educational attainment of their parents. Some commentators believe that such a cycle of poverty and social exclusion may be broken by targeting children in their early years. However, in the aftermath of the global financial and economic crisis and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis, there was an increase in the risk of poverty among children, which may at least in part be attributed to austerity measures and decreasing investment.

EU POLICY MEASURES IN RELATION TO POVERTY AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION AMONG CHILDREN

A European Commission Recommendation, Investing in children: breaking the cycle of disadvantage (2013/112/EU) addressed poverty and social exclusion among children, promoting children’s well-being. It encouraged the EU Member States to go beyond ensuring children’s material security, by promoting equal opportunities so that all children might achieve their full potential, providing a focus on children who faced an increased risk due to multiple disadvantages. It stressed the need to develop integrated strategies based on three pillars:

- access to adequate resources (for example, providing children with adequate living standards through a combination of benefits);

- access to affordable quality services (for example, reducing inequality by investing in early childhood education and care, or improving the responsiveness of health systems to address the needs of disadvantaged children); and

- promoting children’s right to participate (for example, supporting the participation of children in play, recreation, sport and cultural activities).

The European pillar of social rights was proclaimed by EU leaders in November 2017. It is designed to deliver a range of new and effective rights to European citizens, as detailed in 20 key principles. Within Chapter III that covers social protection and inclusion, there is a specific principle covering childcare and support to children. Principle 11 seeks to ensure that children have the right to protection from poverty, with children from disadvantaged backgrounds having the right to specific measures that enhance equal opportunities.

Direct access to

- People at risk of poverty or social exclusion (Europe 2020 strategy) (ilc_pe)

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (ilc_ip)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- EU-SILC ad-hoc modules (ilc_ahm)

- Youth (yth), see:

- Youth social inclusion (yth_incl)

Statistical books and pocketbooks

- Living conditions in Europe — 2018 edition

- Monitoring social inclusion in Europe — 2017 edition

- Quality of life — facts and views — 2015 edition

Statistical working papers

- Income and living conditions (ilc) (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

- Commission Recommendation (2013/112/EU) of 20 February 2013 on Investing in children: breaking the cycle of disadvantage

- Commission Recommendation (2017/761/EU) of 26 April 2017 on the European pillar of social rights

- Regulation (EC) No 1177/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 June 2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

Notes

- ↑ See ‘SPC advisory report to the European Commission on tackling and preventing child poverty, promoting child well-being’of 27 June 2012.

- ↑ Precarious work is non-standard, insecure work without secured labour rights.

- ↑ See ‘Gender equality in the workforce: reconciling work, private and family life in Europe’.

- ↑ J. W. Lynch and G. Kaplan, ‘Socioeconomic position’, in Social Epidemiology, L. F. Berkman and I. Kawachi, Eds., pp. 13-25, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, USA, 2000.

- ↑ See Does money affect children’s outcomes?

- ↑ The overcrowding rate is defined as the proportion of the population living in an overcrowded household. Overcrowded households do not have at their disposal a minimum number of rooms equal to: one room for the household; one room per couple in the household; one room for each single person aged 18 years and over; one room per pair of single people of the same gender aged 12-17 years; one room for each single person aged 12-17 years and not included in the previous category; one room per pair of children aged 0-11 years.

- ↑ Housing deprivation is a measure of poor amenities and concerns households living in a dwelling with a leaking roof, no bath/shower and no indoor toilet, or a dwelling considered too dark. The severe housing deprivation rate is defined as the proportion of the population living in a dwelling which is considered as overcrowded, while also exhibiting at least one of the housing deprivation measures.