Archive:Being young in Europe today - education

Data extracted in July 2020.

Planned article update: November 2022.

Highlights

In 2018, 35 % of children aged less than 3 years in the EU-27 received some formal childcare.

In 2018, the share of EU-27 pupils in primary school learning two or more foreign languages was 6 %; the share for lower secondary school pupils was 59 %.

The share of young people in the EU-27 aged 30-34 years with a tertiary level of educational attainment rose from 31 % in 2009 to 40 % in 2019.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_lang02)

This is one of a set of statistical articles that forms Eurostat’s flagship publication Being young in Europe today.

The right to education for children and young people contributes to their overall development and consequently lays the foundations for success later in life in terms of employability, social integration, health and well-being. Education and training have the potential to play a crucial role in counteracting the negative effects of poverty and social exclusion. The European Union (EU) therefore promotes policies that seek to ensure that all children and young people are able to access and benefit from high-quality education and training.

Each EU Member State is responsible for its own system of education and training, while the EU’s role consists of coordinating and supporting the actions of the Member States as well as addressing common challenges. By so doing, the EU offers a forum for exchange of best practices, gathers and disseminates information and statistics, while providing advice and support for education and training policy reforms.

This article presents a range of statistics covering children’s and young people’s education in the EU, the main sources of data being joint UNESCO-UIS/OECD/Eurostat (UOE) questionnaires on education statistics. Childcare data, coming from the EU’s data collection for statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), complement the information presented for the youngest children. Data on outcomes of education, collected through the EU labour force survey (LFS), are also presented, with information on educational attainment and early school leavers.

Full article

Childcare attendance and participation in education

Early childhood education and care can potentially increase the well-being of young children, advance children’s rights and ensure that all children have a fair start in life. A number of studies during the last decade have shown the crucial role played by early life experiences on cognitive functions, educational attainment and life chances.

Increasing access to high-quality early childhood education and care is one of the key goals outlined within the EU’s strategic framework for education and training (ET2020) which set the goal of having at least 95.0 % of young children (between the ages of four and the compulsory school age) participating in early childhood education by 2020.

Childcare services for children under the age of three years are also covered, as the ‘Barcelona target’ (defined by the European Council in 2002) foresees improving the provision of childcare across the EU Member States through removing some of the disincentives to female labour force participation, such that at least 33.0 % of children under three years of age receive childcare.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of children aged less than three years who were cared for by formal arrangements, namely, in day-care centres; these participation rates are presented by the number of hours during which care is provided (under 30 hours per week or more) which may reflect, at least to some degree, the different patterns of part-time/full-time work of parents across the EU Member States (for example, a particularly high share of the workforce in the Netherlands works on a part-time basis). The information presented should also be considered with respect to different patterns of family structure and attitudes concerning the time that parents (in particular mothers, but also fathers) may or should spend with young children before returning/looking for work. In some southern and eastern EU Member States, it remains relatively common for young children to be cared for by their extended family (often grandparents), whereas families tend to be more dispersed in western and Nordic Member States, which may at least in part explain why they often have a higher demand for and supply of childcare services.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FORMAL AND INFORMAL CHILDCARE?

Formal childcare:

- childcare provided at a day-care centre that is organised/controlled by a public or private body.

Informal childcare:

- childcare provided by a professional child-minder at the child’s home or at the child-minder’s home;

- childcare provided by grandparents, other household members (other than parents), other relatives, friends or neighbours.

In 2018, the lowest levels of formal childcare for children aged less than three years were recorded in eastern EU Member States

In 2018, some 34.7 % of children aged less than three years in the EU-27 received some formal childcare; this share was 1.7 percentage points above the Barcelona target. There were however large differences between the EU Member States: 12 had attained a level of formal childcare that was above the Barcelona target of 33.0 %, with at least half of all children under the age of three years receiving formal childcare in Denmark (63.2 %), Luxembourg (60.5 %), the Netherlands (56.8 %), Belgium (54.4 %), Spain (50.5 %), Portugal (50.2 %) and France (50.0 %). By contrast, less than 1 in 10 children under the age of three years received formal childcare in Czechia and Slovakia (where the lowest share was recorded, at 1.4 %).

Looking at the results by the time spent in formal childcare, more than one third of all children aged less than three years in Denmark, Portugal, Slovenia, Luxembourg, Sweden and Belgium received at least 30 hours of care in 2018. The Netherlands was the only EU Member State where more than one third of all children aged less than three years received between 1 and 29 hours of formal childcare.

Children who have attended pre-primary education tend in most countries to perform better in school than those who have not, even after accounting for their socioeconomic background. Early childhood education may help to build a strong foundation for lifelong learning and to ensure fair access to learning opportunities later in life. Some countries have recognised this by making pre-primary education almost universal for children by the time they are three or four years old [1].

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_caindformal)

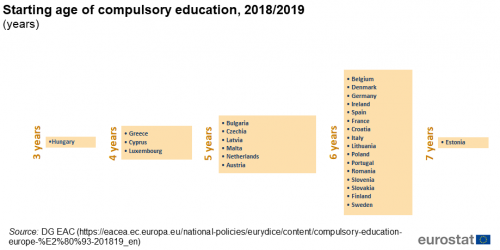

Hungary was the only EU Member State where children started compulsory education at the age of three years during the 2018/2019 school year, while in Greece, Cyprus and Luxembourg children started compulsory education at the age of four. In a majority of the EU Member States the starting age for compulsory education was either five or six years, although it was seven years for children in Estonia. There is a trend within the EU Member States towards requiring children to start education at a younger age, with several countries having lowered their compulsory starting ages and others making pre-school attendance compulsory.

(years)

Source: DG EAC (https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/compulsory-education-europe-%E2%80%93-201819_en)

Since 2000, participation in early childhood education increased steadily across the EU-27

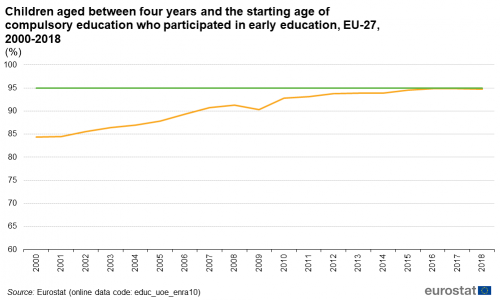

Figure 3 presents statistics for one of the headline targets of the EU’s strategic framework for education and training (ET2020), namely, that the participation rate of children between the age of four years and the starting age of compulsory education should be at least 95.0 % by 2020. Across the EU-27, there was a steady increase in this share from 2000. By 2016, the benchmark level was almost reached (94.9 %). Thereafter, the proportion of children between the ages of four and the starting age of compulsory education in the EU-27 that were participating in early education remained more or less unchanged (94.8-94.9 % during the period 2016-2018). In 2018, the EU-27 participation rate for early education was just 0.2 points below the benchmark target.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_enra10)

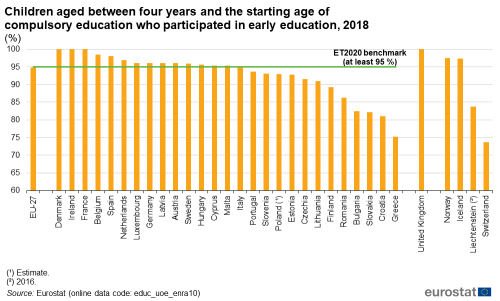

In 2018, there were 14 EU Member States (see Figure 4) where at least 95 % of children aged between four years and the starting age of compulsory education participated in early education. Every child in Denmark, Ireland and France did so, while the other Member States that recorded participation rates of at least 95.0 % included Belgium, Spain, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, Latvia, Austria, Sweden, Hungary, Cyprus and Malta. There were several Member States that recorded participation rates that were close to the ET2020 target, as 90.0-94.9 % of the children aged between four years and the starting age of compulsory education participated in early education in Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, Poland, Estonia, Czechia and Lithuania. This left six Member States where the participation rate was below 90.0 %: of these, there was only one where the share of children participating in early education was below 80.0 %, namely, Greece (75.2 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_enra10)

The number of hours that young children attend formal arrangements (including pre-school education and childcare at day-care centres) is considered an important indicator for a child’s development. Indeed, young children that spend a considerable period of time in such care are likely to receive more individualised instruction and to have more time interacting with their peers. Across the EU-27, some 88.3 % of children from the age of three years to the minimum compulsory school age attended formal childcare arrangements in 2018: more than half (56.1 %) attended at least 30 hours per week of early childhood education and care, while around a third (32.2 %) received between 1 and 29 hours (see Figure 5).

In 2018, the highest share of children between the age of three years and the minimum compulsory school age who received at least 30 hours per week of formal childcare was recorded in Portugal (88.4 %), while more than four out of every five young children also received at least 30 hours of care in Slovenia (85.9 %), Estonia, Latvia (both 84.8 %) and Hungary (83.0 %). At the other end of the range, less than one sixth of children between the age of three years and the minimum compulsory school age received at least 30 hours per week of formal childcare in the Netherlands (15.3 %), while the lowest share was recorded in Romania (13.7 %).

Across all of the EU Member States, a majority of children between the age of three years and the minimum compulsory school age received some form of formal childcare in 2018. In most of the Member States, a higher proportion of children in this age group received at least 30 hours per week of formal childcare rather than 1-29 hours. In 2018, this pattern was particularly apparent in the Baltic Member States, Latvia, Portugal, Bulgaria, Slovenia and Lithuania, where the share of young children receiving formal childcare for at least 30 hours per week was more than 10 times as high as for young children receiving 1-29 hours of care per week. By contrast, more than half of the young children between the age of three years and the minimum compulsory school age received 1-29 hours per week of formal childcare in the Netherlands, Ireland, Greece, Romania, Austria and Spain.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_caindformal)

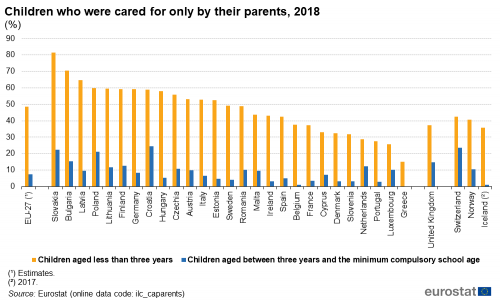

Almost half of all children aged less than three years in the EU-27 were cared for only by their parents in 2018

As shown above, early childhood education and care arrangements vary considerably between the EU Member States. While many parents make use of formal childcare facilities, others choose to care for their children themselves. This is particularly true for very young children, as in 2018 approximately half (48.6 %) of all children aged less than three years in the EU-27 were cared for only by their parents (see Figure 6). The highest share was recorded in Slovakia (81.6 %), while 70.6 % of children aged less than three years were exclusively cared for by their parents in Bulgaria. There were a further 11 Member States where a majority of children aged less than three years were cared for exclusively by their parents. At the other end of the range, between 25 % and 30 % of children aged less than three years were exclusively cared for by their parents in the Netherlands, Portugal and Luxembourg, with a much lower share in Greece (15.1 %).

Comparable data reveal that there was a considerably smaller proportion of somewhat older children who were exclusively cared for by their parents. In 2018, some 7.6 % of children in the EU-27 between the age of three years and the minimum compulsory school age were cared for exclusively by their parents. Much higher shares were recorded in Croatia (24.4 %), Slovakia (22.4 %) and Poland (21.1 %), whereas in Greece, Belgium and Portugal, the share of children between the age of three years and the minimum compulsory school age who were cared for exclusively by their parents stood at less than 3.0 %.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_caparents)

In 2018, more than one quarter of all young children in the EU-27 were cared for informally

Some children are cared for by other types of informal childcare, in other words, they may be cared for by a professional child-minder (at the child’s home or the child-minder’s home), by grandparents, other household members (outside of parents), relatives, friends or neighbours. Figure 7 shows that across the EU-27 more than one quarter of all young children (up to the minimum compulsory school age) were cared for informally. In 2018, the inclination to make use of informal care in the EU-27 was identical for children aged less than three years and for children aged between three years and the minimum compulsory school age (both 25.6 %). Note that informal childcare can — although it does not have to — be combined with formal childcare.

In 2018, more than three fifths (61.4 %) of children aged less than three years in Greece received informal childcare; Slovenia (51.2 %) was the only other EU Member State to report that more than half of its children aged less than three years received such care. By contrast, less than 1 in 10 children aged less than three years received informal childcare in the Nordic Member States of Denmark, Finland or Sweden.

Among somewhat older children, Slovenia, Romania and Czechia were the only EU Member States where, in 2018, a majority of the children between the age of three years and the compulsory school age received informal childcare. At the other end of the range, less than 1 in 10 children from this age group received informal childcare in Spain, Finland, Denmark and Sweden.

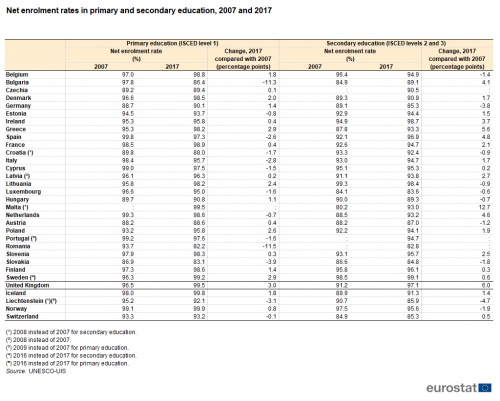

A simple average of enrolment rates among the EU Member States suggests that more than 9 out of every 10 children attended primary or secondary education in 2017

The net enrolment rate in primary (respectively secondary) education is the percentage of children of the primary (respectively secondary) school age who are enrolled in primary (respectively secondary) education.

The net enrolment rate for primary education was 90.0 % or above in 21 of the EU Member States in 2017, rising above 99.0 % in Malta and Sweden. By contrast, Slovakia (83.1 %) and Romania (82.2 %) recorded the lowest shares of children enrolled in the primary education system.

Enrolment rates for secondary education were often slightly lower than those recorded for primary education, which may reflect some older children leaving the system before the end of upper secondary education. Nevertheless, enrolment rates for secondary education were higher than 90.0 % in a majority (20) of the EU Member States for which data are available in 2017 (note that the latest data for Sweden are for 2016). Sweden was the only Member State to record an enrolment rate that was above 99.0 %, while Ireland and Lithuania both had rates that were above 98.0 %. At the other end of the range, enrolment rates for secondary education were less than 90.0 % in Hungary, Bulgaria, Austria, Germany, Slovakia, Luxembourg and Romania (see Table 1). It should be noted that the legal requirements concerning the start and end of compulsory education may be one influence on these enrolment rates (which are expressed as a percentage of the total population of the same age group that officially corresponds to each level).

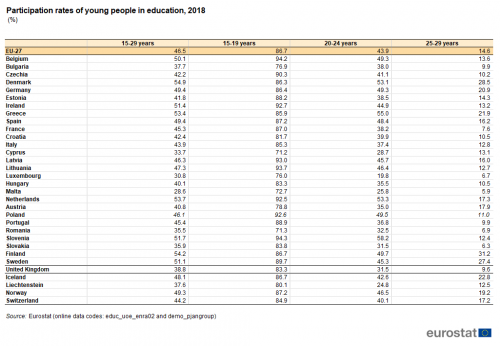

In 2018, there were larger differences between EU Member States concerning enrolment rates for education among young adults than among children

Of the 74.8 million young people aged 15-29 years who were resident in the EU-27 in 2018, almost 35 million were enrolled in education. While the enrolment rate for young people aged 15-29 years averaged 46.5 % across the EU-27 (see Table 2), fewer than one third of all young people in Luxembourg and Malta were enrolled in education; this may be attributed, at least in part, to a relatively high share of young people choosing to study abroad (possibly to study a specific subject that might not be available within the national system) while they remained on the population register (or alternative source of population data) and were therefore considered in the count for the number of inhabitants. By contrast, there were eight EU Member States where more than half of all young people aged 15-29 years were enrolled in an education programme: Denmark had the highest share (54.9 %), followed by Finland (54.2 %), the Netherlands (53.7 %), Greece (53.4 %), Slovenia (51.7 %), Ireland (51.4 %), Sweden (51.1 %) and Belgium (50.1 %).

As may be expected, enrolment rates for young people in education generally decreased as a function of age. For example, while 86.7 % of young people aged 15-19 years in the EU-27 were enrolled in education in 2018, the corresponding share for young people aged 20-24 years was 43.9 %, falling to 14.6 % among young people aged 25-29 years.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_enra02) and (demo_pjangroup)

In 2018, more than two fifths (43.9 %) of young people aged 20-24 years in the EU-27 participated in education, although there were considerable differences between the individual EU Member States. There were four Member States where more than half of all young people aged 20-24 years continued to participate in education, with the highest shares recorded in Slovenia (58.2 %), Greece (55.0 %), the Netherlands (53.3 %) and Denmark (53.1 %). By contrast, less than one third of the young people aged 20-24 years in Romania and Slovakia participated in education, a rate that was around one quarter for this subpopulation in Cyprus and Malta, and around one fifth in Luxembourg.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_enrl1tl), (educ_uoe_enra02) and (demo_pjangroup)

Slightly more than one in eight (14.6 %) young people aged 25-29 years in the EU-27 participated in education in 2018. Finland recorded the highest rate (31.2 %), while the neighbouring Scandinavian Member States of Denmark (28.5 %) and Sweden (27.4 %) recorded the next highest shares. Greece (21.9 %) and Germany (20.9 %) were the only other EU Member States to report that more than one fifth of their young people aged 25-29 years participated in education. By contrast, there were seven Member States where the participation rate in education for young people aged 25-29 years was in single-digits, with this rate less than 7.0 % in Romania, Luxembourg, Slovakia and Malta.

These differences between EU Member States may result from a combination of factors: for example, the country specific organisation of national education systems, legal requirements concerning the end of compulsory education, the accessibility to and affordability of non-compulsory further or higher education, the relative demand for undergraduate (Bachelor’s) and postgraduate (such as Master’s and Doctoral) courses, or different economic situations and their impact on labour markets. After the age of 20, it is more common for enrolment rates to reflect socioeconomic criteria, for example, the employment situation faced by young people (who may remain within the education system if they are unable to find a job) and the cost of studying rather than working.

Between 2008 and 2018, EU-27 education participation rates for young people (20-24 years and 25-29 years) initially followed an upward path, although the progression in participation rates observed between 2008 and 2013 stabilised during the period 2013 to 2018 (see Figures 8 and 9).

In the EU-27, the participation rate of young people aged 20-24 years in education rose from 39.7 % in 2008 to 43.9 % in 2013 and remained unchanged in 2018, an overall increase of 4.2 percentage points. The share of young people aged 20-24 years who participated in education rose between 2008 and 2018 by at least 10.0 points in Ireland, Spain and Croatia, a much faster pace than in the EU-27 as a whole. On the other hand, there were six EU Member States where the share of young people aged 20-24 years participating in education fell between 2008 and 2018: the largest contractions were recorded for Romania (13.6 points), Lithuania (8.4 points) and Hungary (5.5 points), while the reductions in Finland, Poland and Estonia were less than 4.0 points.

The share of young people aged 25-29 years in the EU-27 who participated in education rose from 11.8 % in 2008 to 14.9 % in 2013, before falling back slightly to 14.6 % in 2018; these developments may reflect the lack of employment opportunities that were available in several EU Member States in the aftermath of the global financial and economic crises, which may have led some students to consider extending their education or indeed returning to education in order to improve their qualifications. This was particularly apparent in Greece, where the participation rate of young people aged 25-29 years jumped dramatically from 12.6 % in 2008 to 33.7 % in 2013, before returning to 21.9 % in 2018. In keeping with the developments observed for young people aged 20-24 years, participation rates of young people aged 25-29 years generally rose between 2008 and 2018; this was the case in 18 out of 27 Member States. While participation rates in Greece, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg and Spain were at least 5.0 percentage points higher in 2018 than they had been in 2008, the participation rate of young people aged 25-29 years in education fell by at least 4.0 points between 2008 and 2018 in Slovenia and Portugal and by as much as 7.1 points in Romania.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_enrl1tl), (educ_uoe_enra02) and (demo_pjangroup)

Foreign language learning

The ability to speak one or more foreign languages promotes intercultural dialogue, improves employability of individuals and the efficiency of enterprises that trade across borders and facilitates the movement of individuals.

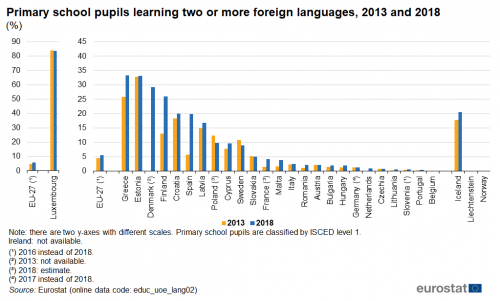

In 2016, the share of EU-27 pupils in primary school (ISCED level 1) learning two or more foreign languages was 5.6 %. This figure was 1.0 percentage points higher than in 2013.

Figure 10 shows that Luxembourg topped the ranking of foreign language learning among the EU Member States, with more than 8 out of every 10 pupils at primary school learning two or more foreign languages in both 2013 (83.8 %) and 2018 (83.6 %). This was considerably higher than in any of the other Member States as the next highest shares in 2018 were recorded in Greece (33.4 %) and Estonia (33.2 %), while Denmark, Finland and Croatia recorded shares within the range of 20.0-30.0 %. By contrast, in a majority of the Member States, less than 5.0 % of primary school pupils learnt two or more foreign languages in 2018 (2017 data for Germany and 2016 data for Slovenia).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_lang02)

A comparison between 2013 and 2018 shows that in many of the EU Member States there was little change in the share of pupils at primary school who were learning two or more foreign languages; this is perhaps unsurprising given the rate at which the school curriculum may change and the need to invest in additional resources and qualified staff for teaching new subjects. That said, the number of pupils learning two or more foreign languages rose by 14.1 percentage points in Spain, by 12.9 points in Finland and by 7.5 points in Greece during the period under consideration. On the other hand, the share of pupils learning two or more foreign languages fell in five Member States. The biggest reductions were in Poland (down 2.6 points) and Sweden (down 1.9 points).

THE ISCED CLASSIFICATION

The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) is an instrument based on standard concepts and definitions that may be used to assemble, compile and present comparable statistics and indicators on education. The ISCED 2011 classification was adopted by the UNESCO General Conference at its 36th session in November 2011. Eurostat has applied the use of this classification for its administrative data on education statistics from reference year 2013 onwards.

The notion of ‘levels’ of education within ISCED is based on grouping education programmes in relation to learning experiences, as well as the knowledge, skills and competencies which each programme is designed to impart. The ISCED level reflects the degree of complexity and specialisation of the content of an education programme:

01 Early childhood educational development — designed to support early development in preparation for participation in school and society; programmes targeting children under three years old;

02 Pre-primary education — designed to support early development in preparation for participation in school and society; school or centre-based for children aged at least three years through to the start of compulsory primary education;

1 Primary education — programmes that are typically designed to provide students with fundamental skills in reading, writing and mathematics, establishing a solid foundation for learning;

2 Lower secondary education — the first stage of secondary education that aims to build on primary education, typically with a more subject-oriented curriculum;

3 Upper secondary education — the second stage of secondary education preparing for tertiary education and/or providing skills relevant to employment (usually has an increased range of subject options and streams);

4 Post-secondary non-tertiary education — programmes that are designed to provide learning experiences that build on secondary education and prepare students for labour market entry and/or tertiary education; content is broader than secondary education, but not as complex as tertiary education;

5 Short-cycle tertiary education — programmes that are typically practical and occupationally-specific, preparing students for labour market entry or providing a pathway to other tertiary programmes;

6 Bachelor’s or equivalent level — programmes designed to provide intermediate academic and/or professional knowledge, skills and competencies leading to a first tertiary degree or equivalent qualification;

7 Master’s or equivalent level — programmes designed to provide advanced academic and/or professional knowledge, skills and competencies leading to a second tertiary degree or equivalent qualification;

8 Doctoral or equivalent level — programmes designed primarily to lead to an advanced research qualification, usually concluding with the submission and defense of a substantive dissertation of publishable quality based on original research.

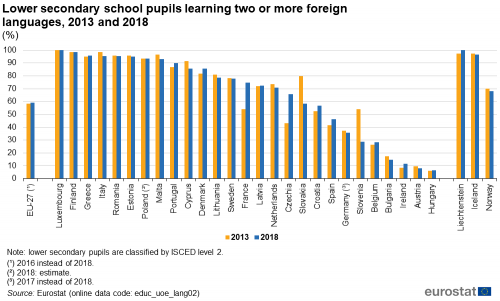

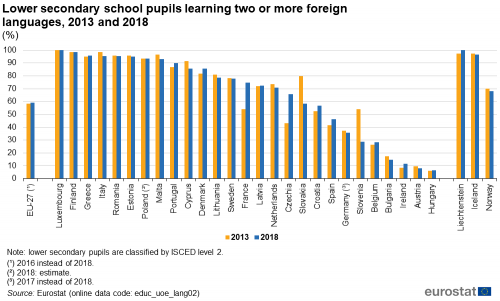

In the vast majority of the EU Member States, the curricula for secondary education includes at least one foreign language. Figure 11 reveals that a higher share of pupils in lower secondary education (ISCED level 2) were learning two or more foreign languages than the share recorded for primary education. In 2016, almost three fifths (59.2 %) of lower secondary school pupils in the EU-27 were learning two or more foreign languages.

Among the EU Member States, all of the lower secondary pupils in Luxembourg in 2018 learnt two or more foreign languages, while this share ranged from 93.2-98.6 % in Finland, Greece, Italy, Romania, Estonia, Poland and Malta. There were a further 11 Member States where more than half of all lower secondary pupils in 2018 were learning two or more languages. By contrast, only 6.5 % of lower secondary pupils in Hungary were learning two or more foreign languages, a share that stood at 7.9 % in Austria; these were the only Member States to record single-digit shares.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_lang02)

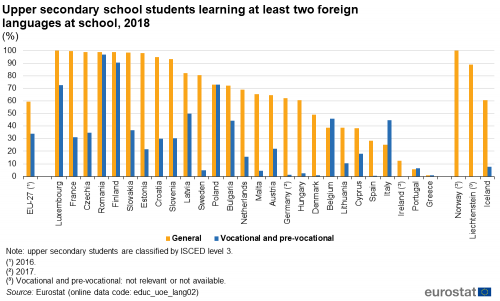

Learning foreign languages in upper secondary schools: usually more common among students following general rather than vocational programmes

Figure 12 depicts the situation for foreign language learning in upper secondary education (ISCED level 3) by programme orientation: either general or vocational/pre-vocational. Across the EU-27, 59.4 % of pupils enrolled in general upper secondary schools were learning at least two foreign languages in 2016, compared with 34.1 % of pupils who were enrolled in vocational/pre-vocational upper secondary education.

In 2018, it was relatively commonplace to find that a high proportion of students following general upper secondary programmes were being taught at least two foreign languages. This was the case for every student in Luxembourg (100.0 %), while shares of more than 95.0 % were also recorded in France, Czechia, Romania, Finland, Slovakia and Estonia. Learning two or more foreign languages in general upper secondary education was quite uncommon in Greece (1.0 %), Portugal (5.8 %) and Ireland (12.5 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_lang02)

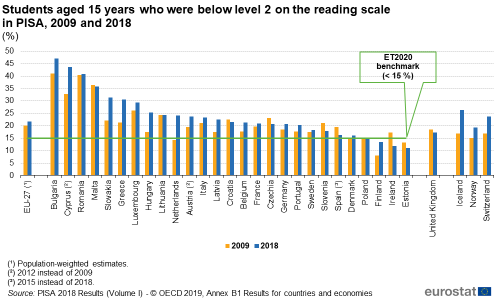

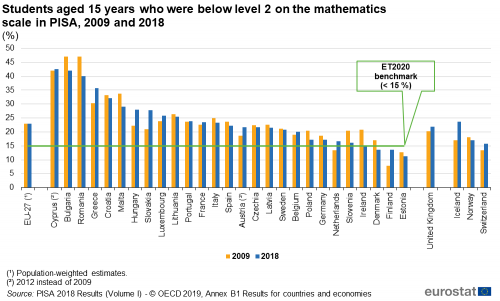

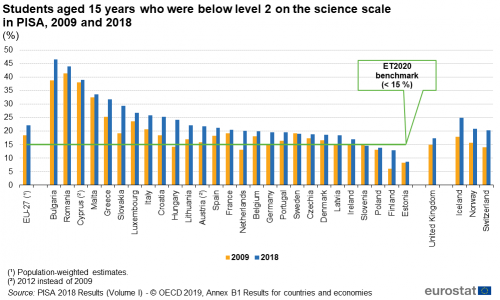

Reading, mathematical and science skills: identifying where there is room for an improvement in basic skills

Competences in reading, mathematics and sciences are considered to be basic skills that can be applied to successful professional and civic lives. These skills also promote participation in a knowledge-based society and may contribute towards the competitiveness of modern economies. As such, the Council adopted an EU-wide benchmark within the ET2020 framework to reduce the proportion of 15 year-olds underachieving in these key areas of learning, to less than 15 % by 2020.

WHAT IS PISA?

The PISA (Programme for international student assessment) survey is an internationally standardised assessment, developed by the OECD and conducted in all EU Member States (as well as a number of non-member countries), that measures the knowledge and skills of students aged 15 years in reading, mathematics and science; it also collects contextual information on the individual characteristics and socioeconomic background of students. The PISA scores are divided into six proficiency levels ranging from the lowest (level 1) to the highest (level 6): low achievement is defined as performance below level 2.

PISA results on low-achievers in reading literacy for 2018 reveal considerable differences across the EU Member States. Estonia, Ireland and Finland stood out as they had relatively few low-achievers in reading competence (11.1-13.5 %); Poland (14.7 %) was the only other Member State to record a share below the ET2020 framework target of 15 %. At the other end of the scale, more than 4 in 10 students aged 15 years in Bulgaria, Cyprus and Romania recorded a PISA score that was below level 2 on the reading scale, while Malta also reported that more than one third of its 15 year-old students were low-achievers in reading.

In PISA, reading literacy is defined as understanding, using and reflecting upon written texts, in order to achieve one’s goals, to develop one’s knowledge and potential and to participate in society.

Between 2009 and 2018 there was a modest increase (1.7 percentage points) in the share of EU-27 students aged 15 years who were below level 2 on the PISA reading scale. A majority (18 out of 27) of the EU Member States saw a deterioration in reading skills during this period, with the share of 15 year-olds who were below level 2 rising by 9.2-9.8 points in Greece, Slovakia and the Netherlands, and by 10.9 points in Cyprus (during the period 2012-2018). By contrast, the proportion of low-achievers fell at a relatively rapid pace between 2009 and 2018 in Ireland (5.4 points), Spain (3.3 points during the period 2009-2015) and Slovenia (also 3.3 points).

Figure 14 presents similar data with a focus on students who were below level 2 on the PISA mathematics scale. By this measure, close to one quarter (23.0 %) of the students aged 15 years in the EU-27 were considered low-achievers in mathematics in 2018. Estonia, Finland, Denmark and Ireland were the only EU Member States where the share of low-achievers in mathematics was already at or below the ET2020 target of 15 %. By contrast, the highest shares of low-achievers were recorded in Cyprus and Bulgaria (both over 40 %), while Romania, Greece and Croatia each reported shares within the range of 30-40 %.

As for low-achieving students in reading, there was little (or no) change between 2009 and 2018 in the share of students aged 15 years in the EU-27 who were low-achievers in mathematics; this share remained unchanged at 23.0 %. In Romania, Ireland, Bulgaria, Malta and Slovenia, the share of low-achievers fell by 4.2-7.1 points. On the other hand, in Slovakia, Finland, Hungary and Greece, the proportion of low-achievers in mathematics increased by 5.4-6.7 points.

The final set of information in relation to PISA scores concerns low-achievers in science (see Figure 15). The share of EU-27 students aged 15 years who were below level 2 on the PISA science scale was over one fifth (22.2 %) in 2018; this could be compared with 2009, when the proportion of low-achievers in science had been 3.7 percentage points lower, at 18.5 %.

In 2018, Estonia, Finland, Poland and Slovenia were the only EU Member States that recorded shares of low-achieving students in science below the ET2020 target of (at most) 15 %. A majority (16 out of 27) of the Member States recorded shares of low-achievers in science that were at or above 20 %, reaching 39.0 % in Cyprus, 43.9 % in Romania and peaking at 46.5 % in Bulgaria.

Contrary to the other two subjects, there was a relatively clear pattern across the EU Member States with respect to developments for low-achievers in science. Between 2009 and 2018, the share of low-achievers rose in all but two of the Member States, with the proportion of low-achievers increasing by 10.0 percentage points in both Hungary and Slovakia, while the share also rose by a considerable margin — within the range of 6.1-7.7 points — in Bulgaria, Croatia, Finland, the Netherlands, Greece and Austria (2012-2018). The two Member States that reported a fall in their share of low-achievers in science were Slovenia and Sweden; in both cases the change was modest.

The 2018 results from the PISA survey suggest that students from individual EU Member States tend to have similar skills levels for reading, mathematics and science; this may well be linked to the general organisation of education systems country-wide. There were relatively few low-achievers among students aged 15 years in Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Slovenia and Finland for all three disciplines: indeed, all five systematically appeared among the seven Member States with the lowest shares for all three subjects. Poland was also present in the list of the seven Member States with the lowest shares of low-achievers for reading and science (and had the eighth lowest rate for low-achievers in mathematics).

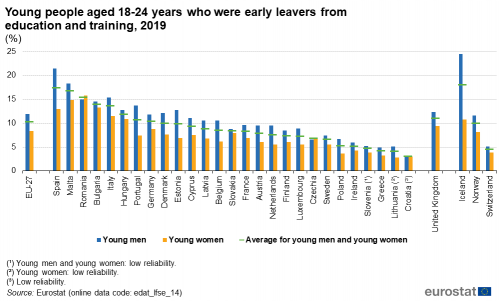

Early school leavers: situation improving in almost all EU Member States, especially for women

Secondary education is an important stage in an individual’s personal and professional development. Some young people leave the education system without the necessary skills that allow them to integrate successfully in the labour market. With this in mind, policymakers across the EU have sought measures that may help reduce the number of students leaving early from school or more generally education and training. The strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training (ET2020) set a target whereby the proportion of early leavers from education and training in the EU-27 should fall to less than 10 % by 2020. When transposing this strategy into individual plans, EU Member States set national targets reflecting their different starting positions and national circumstances.

WHO IS CONSIDERED AN EARLY LEAVER?

‘Early leavers from education and training’ refers to persons aged 18-24 years with at most a lower secondary level of educational attainment and who are no longer in education or training.

In 2019, the proportion of young people aged 18-24 years in the EU-27 who were considered as early leavers from education and training stood at 10.2 % (just above the ET2020 target of less than 10.0 %). There were 19 EU Member States where the share of young people who were early leavers from education and training was already below 10.0 %, while there were 16 where the latest rate met or was lower than the their national target (see Figure 16). The share of early leavers was particularly low in Croatia (3.0 %), Lithuania (4.0 %), Greece (4.1 %) and Slovenia (4.6 %). By contrast, the highest rates were observed in Spain (17.3 %), Malta (16.7 %) and Romania (15.3 %).

Although Spain and Malta recorded the highest rates among the EU Member States, they also recorded some of the biggest decreases in their respective shares of early leavers from education and training over the period between 2009 and 2019. The largest decrease (20.3 points) was recorded among early leavers from Portugal, with reductions of 13.6 points observed in Spain, 10.1 points in Greece and 9.0 points in Malta. More generally, the share of early leavers fell in the vast majority of the Member States. Slovakia, Czechia and Hungary were the only exceptions as they reported a higher proportion of young people aged 18-24 years had left education and training with at most a lower secondary level of educational attainment in 2019 than in 2009.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_14)

A higher share of young men (11.9 %) than young women (8.4 %) across the EU-27 left education and training early in 2019. This pattern was repeated in 25 out of the 27 EU Member States, with slightly higher shares for young women in Romania and Czechia. The most pronounced gender gaps — with shares for young men that were at least 5.0 percentage points higher than those for young women — were recorded in Spain, Portugal and Estonia (see Figure 17). It is interesting to note that in both Portugal and Estonia, the share of early leavers among young men was higher than the EU-27 share, while the share of early leavers among young women was below the EU-27 share; this situation was also observed in Denmark which had the fourth highest gender gap (4.5 points).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_14)

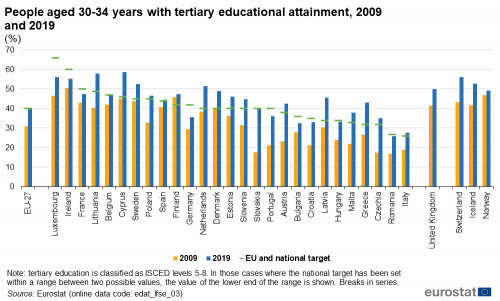

Tertiary education: an increasing number of graduates, especially among women

Tertiary education (ISCED levels 5-8) — provided by universities and other higher education institutions, such as colleges and institutes of technology — plays a key role in knowledge-based societies. This is another area where an ET2020 target has been set by policymakers, namely, that at least 40 % of the population aged 30-34 years should have a tertiary level of education by 2020. As with the indicator for early leavers from education and training, this target was transposed into national targets to reflect the specific situations of each EU Member State (see Figure 18).

Across the EU-27, in 2019 just over two fifths (40.3 %) of the population aged 30-34 years had completed a tertiary level of education (0.3 percentage points above the ET2020 target). There were 18 EU Member States that reported that more than 40.0 % of people aged 30-34 years had a tertiary level of education, while 18 had already surpassed their national targets for 2020.

In 2019, more than half of all people aged 30-34 years had a tertiary level of educational attainment in Cyprus, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Ireland, Sweden and the Netherlands. By contrast, there were nine EU Member States where this share was below 40 %, among which the lowest levels of tertiary educational attainment were recorded in Italy and Romania (both had shares that were less than 30 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_03)

Compared with 2009, the share of people aged 30-34 years in the EU-27 with a tertiary level of educational attainment was 9.2 percentage points higher in 2019. All of the EU Member State recorded an increase in their shares of young people with a tertiary level of educational attainment during this period. The biggest increases were seen in Slovakia (an increase of 22.5 points), Austria (19.0 points), Czechia (17.6 points) and Lithuania (17.4 points), while Greece, Malta, Latvia, Portugal, Cyprus, Poland, Slovenia, the Netherlands and Croatia also recorded double-digit increases.

The proportion of women aged 30-34 years with a tertiary level of educational attainment was higher than that recorded for men of the same age in all of the EU Member States (see Figure 19). In Germany there was a relatively small difference between the sexes, as the share of young women with a tertiary level of educational attainment was just 0.8 percentage points higher than the corresponding rate for young men. At the other end of the range, the largest gender gaps (with rates for women more than 20 points higher than for men) were recorded in the Baltic Member States and Slovenia; the largest gap was in Estonia (26.5 points).

(percentage points difference, % share for women - % share for men)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_03)

Quality of childcare and education

High-quality early education and childcare for young children is thought to improve their health and promote their development and learning. Indeed, high-quality, affordable care and pre-primary education coupled with after-school services are considered key aspects in this respect. Measuring the quality of formal childcare and education is difficult since there is no single indicator that adequately reflects the quality of the educational environment and the interaction between teachers and pupils. That said, a variety of different indicators may be employed to help form an opinion on developments, for example, average class sizes or child-to-staff ratios (where lower ratios may imply a better quality).

The ratio of pupils to teaching staff in pre-primary education (ISCED level 02) is shown in Figure 20. Based on the information that is available for 2017 (no data for nine of the EU Member States), pupil-to-teacher ratios ranged from 8.5 in Estonia and less than 10.0 pupils per member of teaching staff in Slovenia (note the coverage is different), Germany and Finland up to 16.8 pupils per teacher in Portugal, with a peak of 22.6 pupils per teacher in France.

Figure 21 presents similar information for pupil-teacher ratios in primary and lower secondary education (as covered by ISCED levels 1 and 2). In 2018, the ratio of pupils to teachers across the EU-27 was somewhat higher in primary education (13.6 : 1) than it was for lower secondary education (12.0 : 1). This pattern was repeated in all but three of the EU Member States, with Poland, Luxembourg and Hungary being the only exceptions with a higher ratio of pupils to teachers in lower secondary education (than in primary education); note that all three of these Member States had relatively low overall ratios of pupils to teachers for both primary and lower secondary education.

Within primary education, the highest ratios of pupils to teachers were recorded in Romania, Czechia and France, where there were on average 19-20 pupils per teacher in 2018. This was approximately twice as high as the ratios recorded in Luxembourg, Greece and Poland, which were the only EU Member States to report that they had an average of less than 10.0 pupils for every teacher within primary education.

In 2018, there were 11 EU Member States where the ratio of pupils to teachers in lower secondary education was lower than 10.0 : 1. The lowest ratio was recorded in Slovenia (2017 data) at 6.0 : 1. At the other end of the range, the highest ratios were recorded in the Netherlands (16.1 : 1), France (14.4 : 1) and Germany (13.0 : 1).

(ratio, based on full-time equivalents)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_perp04)

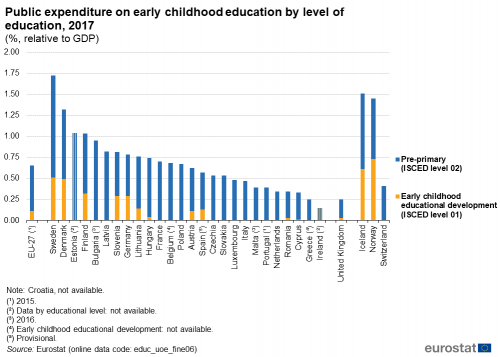

How much do the EU Member States spend on education?

A relatively strong link between educational expenditure and the performance of education sectors may be expected, whereby improvements in education systems are driven, at least in part, by increased investment in childcare, early childhood education and more general education services. Public expenditure on early childhood educational development and pre-primary education may provide support to families with young children participating in formal day-care services and/or pre-school institutions (including kindergartens and day-care centres). Most countries spend more on pre-primary education than they do on early childhood educational development, which probably reflects the fact that a larger number of children are covered by the former. Apart from this exception, expenditure tends to gradually increase as a function of higher levels of education.

Figure 22 shows that total public spending on early childhood education rarely accounted for more than 1.0 % of gross domestic product (GDP). Of the 26 EU Member States for which 2017 data are available (no information for Croatia), the total expenditure on early childhood education relative to GDP stood at 1.0 % or more in Sweden (1.7 %), Denmark (1.3 %), Estonia and Finland (both 1.0 %). At the other end of the range, there were seven Member States where such expenditure was less than 0.4 % of GDP, the lowest ratio being recorded in Ireland (0.2 %).

(%, relative to GDP)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_fine06)

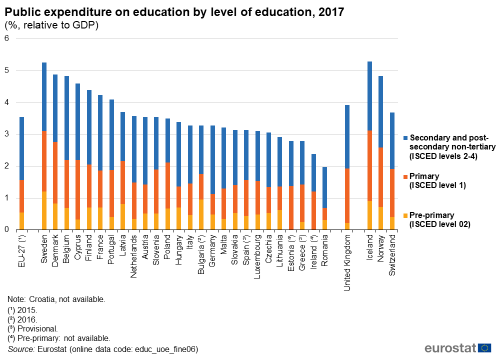

Figure 23 provides similar data relating to public expenditure for pre-primary, primary, and secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education. In 2015, EU-27 public expenditure on primary education was 1.0 % of GDP, while spending on secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education was 2.0 %.

In 2015, total public expenditure on pre-primary, primary, and secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED levels 02-4) in the EU-27 was 3.6 % of GDP. Among the EU Member States, this ratio ranged in 2017 from more than 4.5 % in Sweden, Denmark, Belgium and Cyprus, down to 2.0 % in Romania.

(%, relative to GDP)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_fine06)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Eurostat’s education statistics provide comparable information on key aspects of the education systems of the EU Member States. Data cover a range of different areas, including: enrolment and participation in education programmes by pupils and students, education and training outcomes, learning mobility among students, language learning, education personnel and expenditure on education.

One of the main sources of annual data on education is a joint questionnaire on education statistics that is overseen by the United Nations Institute for Statistics (UNESCO-UIS), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Eurostat; the data are compiled on the basis of national administrative sources, as reported by ministries of education or national statistical offices. Commission Regulation (EU) No 912/2013 concerning the production and development of statistics on education and lifelong learning is the legal basis for these data from school year 2012/2013 onwards.

Data on formal and informal childcare are derived as secondary statistics from EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). Regulation (EU) No 1177/2013 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) provides the legal basis for the collection of these indicators. Statistics on educational attainment and early leavers are derived as secondary statistics from the EU’s labour force survey (LFS). Council Regulation (EC) No 577/98 provides the legal basis for the organisation of a labour force sample survey across the EU; it provides a broad range of statistics on the labour market for both an annual and infra-annual periodicity which may be used, among other purposes, to monitor the ET2020 strategy, the European employment strategy or economic and monetary policy in the EU.

Context

STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK — EDUCATION AND TRAINING 2020

The strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training 2020 (ET2020) was drawn up in 2009 with the aim of supporting EU Member States to develop their educational and training systems so that these encouraged all citizens to realise their full potential, by: making lifelong learning and mobility a reality; improving the quality and efficiency of education and training; promoting equity, social cohesion and active citizenship; enhancing creativity and innovation, including entrepreneurship.

In order to measure progress achieved on these objectives, the framework defines a set of targets to be achieved by 2020, namely:

- at least 95 % of children (from the age of four to the minimum compulsory school age) should participate in early childhood education;

- fewer than 15 % of 15-year-olds should be under-skilled in reading, mathematics and science;

- fewer than 10 % of young people aged 18-24 years should drop out of education and training;

- at least 40 % of people aged 30-34 years should have completed some form of higher education;

- at least 15 % of adults should participate in lifelong learning;

- at least 20 % of higher education graduates and 6 % of persons aged 18-34 years with an initial vocational qualification should have spent some time studying or training abroad;

- the share of employed graduates aged 20-34 years with at least an upper secondary level of educational attainment and having left education 1-3 years ago should be at least 82 %.

EUROPEAN STRATEGY FOR MULTILINGUALISM

At the 2002 Barcelona European Council, targets were set for the ‘mastery of basic skills, in particular by teaching at least two foreign languages from a very early age‘. Since then, linguistic diversity has been encouraged throughout the EU, in the form of learning in schools, universities, adult education centres and company training.

The European Commission adopted in 2008 the Communication Multilingualism: an asset for Europe and a shared commitment (COM(2008) 566 final), which was followed by a Council Resolution on a European strategy for multilingualism (2008/C 320/01). Addressing multilingualism in the broader context of social cohesion and economic prosperity, the Communication urged the EU Member States to do more in order to achieve the Barcelona objective of enabling the citizens of the EU to communicate in two languages in addition to their mother tongue.

In 2014, these recommendations were endorsed in the Council Conclusions on multilingualism and the development of language competences which stated that EU Member States should assess and monitor progress in developing language competences in the national context; such assessments should cover all four language skills — reading, writing, listening and speaking. EU Member States agreed to adopt and improve measures aimed at promoting multilingualism from an early age and at enhancing the quality and efficiency of language learning and teaching. This vision was confirmed by a Council Recommendation on a comprehensive approach to the teaching and learning of languages (2019/C 189/03) that was adopted by education ministers in May 2019.

Direct access to

- Participation in education and training (t_educ_part)

- Education and training outcomes (t_educ_outc)

- Living conditions (t_ilc_lv)

- Childcare arrangements (t_ilc_ca)

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

- Education personnel (educ_uoe_per)

- Education and training outcomes (educ_outc)

- Graduates (educ_uoe_grad)

- Transition from education to work (edatt)

- Languages (educ_lang)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

- Childcare arrangements (ilc_ca)

- Youth (yth), see:

- Youth education and training (yth_educ)

- Education administrative data from 2013 onwards (ISCED 2011) (ESMS metadata file — educ_ueo_enr_esms)

- Households statistics — LFS series) (ESMS metadata file — lfst_hh_esms)

- Income and living conditions (ilc) (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

- Population by educational attainment level (based on EU-LFS) (ESMS metadata file — edat1_esms)

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 912/2013 of 23 September 2013 implementing Regulation (EC) No 452/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the production and development of statistics on education and lifelong learning, as regards statistics on education and training systems

- Communication from the Commission COM/2008/0566 final of 18 September 2008 on multilingualism: an asset for Europe and a shared commitment

- Council conclusions 2014/C 183/06 of 20 May 2014 on multilingualism and the development of language competences

- Council Recommendation 2019/C 189/03 of 22 May 2019 on a comprehensive approach to the teaching and learning of languages

- Council Resolution 2008/C 320/01 of 21 November 2008 on a European strategy for multilingualism

- Presidency conclusions — Barcelona European Council, 15 and 16 March 2002

- European Commission — Education and training monitor

- Eurydice — Key data on early childhood education and care in Europe, 2019

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) — Education

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) — Education at a glance 2019

- UNESCO — Education

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics

Notes

- ↑ OECD, Education at a glance, ‘Chapter C: Access to Education, Participation and Progression’, Paris, 2011.